CONTENTS

Excitement in Chicago – I

Excitement in Chicago – II

Excitement in Chicago – III

Major League Beaver

Piersall's Month

Most Watched Event

Stick to Boxing, Tim

Yips Can Strike Anyone

Baseball

Vignettes Index

Baseball

Page

Golden Rankings Home

Top of Page

|

Baseball Vignettes - VIII

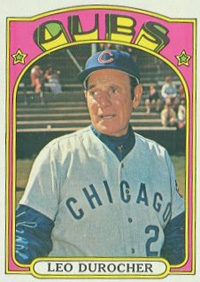

Excitement in Chicago – I

Prior to the start of the 1966 season, the city of Chicago was abuzz with excitement. The chief causes were the new managers of the Cubs and White Sox.

|

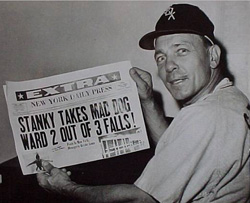

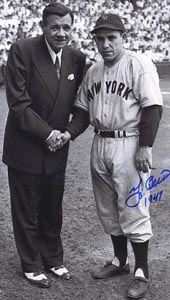

Leo Durocher made no secret of the fact that Eddie Stanky was one of his favorite players. Leo's famous statement "He can't hit, he can't field, he can't run. All he can do is beat you." was made about Eddie. "The Lip" first managed "The Brat" from 1944-7 in Brooklyn. Then, after Leo took over the New York Giants, he traded four players to the Boston Braves for 2B Stanky and SS Alvin Dark after the 1949 season. The DP combo was a cog in the Giants' pennant in 1951 (along with a young guy named Mays). The footage of Bobby Thomson's trot around the bases after winning the '51 pennant with "The Shot Heard 'Round the World" shows Stanky (in a jacket) running from the 1B dugout to the 3B coaching box to embrace Leo just as Bobby arrives.

Durocher had not managed since the Giants fired him after the 1955 season. Stanky left the Giants after 1951 to manage the St. Louis Cardinals until 1955. In the eleven years since, he had turned down five offers to skipper other ML clubs. Now each man had received a three-year contract to manage in the same town - Leo on the North Side and Eddie on the South.

Eddie Stanky

|

Their clubs had been on decidedly different paths.

- The Cubs had not finished in the first division in 20 years. The past two seasons, when the NL established attendance records (primarily because of the addition of the Houston Astros and New York Mets), crowds at Wrigley Field dropped 35%. From 1961-5, they had experimented with the coaches taking turns running the team. In short, Leo didn't have a tough act to follow.

- The White Sox had won the pennant in 1959 and had been out of the first division only once since 1950. In 1964, they lost to the Yankees by one game. They finished second again in '65, this time to the Minnesota Twins. Stanky did have a tough act to follow: Al Lopez, who had retired after nine years at the helm.

Given the track records of the two as feisty, competitive, do-anything-to-win players and managers, Chicagoans were "anticipating a season filled with controversy, daring, brawls and intrigue."

- During one off-season week, Durocher and Stanky participated in more than 200 radio and TV interviews.

- The Cubs' season ticket sales increased 35%.

- The White Sox banked over $1 million in advance sales. Demand was higher than even 1960 after winning the pennant.

- Bill Veeck, former owner of the Cleveland Indians and St. Louis Browns and a native Chicagoan: "I figure that having Durocher and Stanky managing again almost balances baseball's loss of Casey Stengel" [who had retired after managing the expansion Mets for four years].

After all the anticipation, how did Leo and Eddie do?

Continued below ...

Reference: "Two Headliners Take over Chicago," William Leggett, Sports Illustrated, February 28, 1966

Excitement in Chicago – II

Part I talked about the buzz in Chicago before the 1966 season over the hiring of Leo Durocher by the Cubs and Eddie Stanky by the White Sox. So what happened? Was the excitement justified?

Let's take the Cubs first. Certainly, The Lip's first year proved a major disappointment. Chicago fell into tenth place, seven and a half games behind even the lowly New York Mets and 36 games behind the pennant-winning Dodgers. The joke in Chicago was that Leo, upon taking the job, had declared, "The Cubs are not an eighth-place team," then proved himself right by managing them to tenth place! The Cubs also dropped from 9th to 10th in attendance.

However, Durocher's makeover of the team paid off in 1967 with a 28-game improvement to third behind the Cardinals and Giants – Chicago's best finish since the 1945 pennant. Leo's boys led the league in runs/game with 4.1 with a lineup that featured 3B Ron Santo (.300/31HR/98RBI), 1B Ernie Banks (.276/23/95), and LF Billy Williams (.278/28/84). The infield was one of the best in the league with a DP combo of SS Don Kessinger and 2B Glen Beckert. Attendance improved by 300,000. Ferguson Jenkins led the staff with 20 victories. Leo was the toast of the town.

The '68 Cubs, with basically the same lineup, again finished third to prove that '67 was no fluke. Fergie again won 20, and Bill Hands added 16. Attendance passed the million mark for the first time since 1952. This set the stage for the memorable '69 season.

|

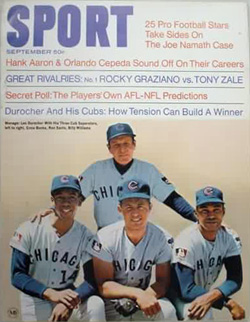

Durocher with (L-R) Ernie Banks, Ron Santo, Billy Williams |

Ferguson Jenkins |

1969 was the first year of divisional play in MLB. San Diego and Montreal gave the NL 12 teams divided into East and West Divisions. In defiance of geography, the Cubs and Cardinals were placed in the East while Atlanta and Cincinnati went West.

- Still bolstered by the "Big Six" (Hundley, Banks, Beckert, Kessinger, Santo, and Williams), the Cubs improved to 92 wins, the most since '45.

- In many years, that would win a division but the "Miracle Mets" won 100.

- The Cubs led from Day One through September 9 when they lost their second straight to the Mets at Shea as part of an eight-game losing streak and 11-of-12 Ls.

- Fergie won 21, and Hands improved to 20. Ken Holtzman captured 17. However, the Mets rode their splendid young staff of Tom Seaver (25 wins), Jerry Koosman (17), and Gary Gentry (13) to the World Series championship.

- Wrigley Field attendance set a record of 1,674,993.

|

The Cubs' collapse down the stretch caused criticism of Durocher for not resting his starters enough. Kessinger slumped badly as did 38-year old Banks, who hit .186 with only one homer in September. However, many analyses of the season conclude that it was more a case of the Cub lineup overperforming early in the year than underperforming near the end. Another factor was the "hole" in CF that rookies Don Young and Jim Qualls couldn't fill.

The '70 Cubs again started fast, leading the East from April 21 to June 23. They ran third most of the rest of the season until a late spurt brought them to second, five games behind the Pirates. The attendance was nearly the same: 1,642,705. Jim Hickman played most of the games at first for Banks. Johnny Callison improved the RF position, but Cleo James (.210) wasn't the answer in CF. Steady Fergie climbed another game to 22 while Hands won 18 and Holtzman 17.

With Joe Pepitone at first, the Cubs slid to third in '71. Brock Davis improved CF (which isn't saying much) but Callison faded in RF. Jenkins kept his incredible string going with 24 wins.

Chicago moved back to second in '72, 11 behind Pittsburgh in the East. CF Rick Monday and RF Jose Cardenal improved the OF. Fergie "slumped" to 20 victories, and 33-year old Milt Pappas accumulated 17. However, Durocher didn't make it to the end of the season. On July 25, the Cubs announced that the "cantankerous" manager had "stepped aside," apparently at the strong suggestion of owner Philip K. Wrigley after a three-hour meeting. The action was the culmination of two years of friction between Leo and the players, especially Banks and Santo. Leo had been frustrated because he had to play Ernie because of his hero status despite the fact that he could no longer produce. Durocher also felt Santo didn't come through in big games.Leo managed the Astros for the final 31 games of that season and all of '73 before retiring for good.

Bottom line: Did Durocher bring excitement to Wrigley Field? You bet. But he could never get the Cubs over the hump and win the pennant. David Claebaut has written a book entitled Durocher's Cubs: The Greatest Team That Didn't Win. I don't agree with the title, but it shows how The Lip's era is remembered by Cubs fans.

Excitement in Chicago – III

Part I talked about the buzz in Chicago before the 1966 season over the hiring of Leo Durocher by the Cubs and Eddie Stanky by the White Sox. Part II discussed how Durocher improved the Cubs. Now we consider how the White Sox responded to Stanky.

Eddie took the second place team he inherited from Al Lopez and managed it to consecutive fourth place finishes.

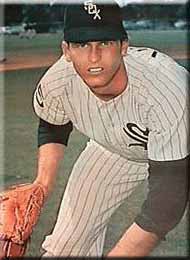

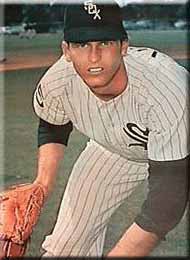

Tommy John |

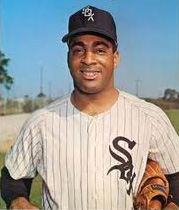

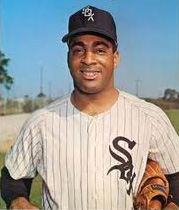

- 1966: The Sox struggle to finish over .500 at 83-79, 15 behind the Baltimore Orioles. 23-year-old Tommy John wins 14 for the second straight year to lead the hurlers. Another 23-year-old, CF Tommie Agee, tops the hitters in BA (.273), HR (22) and RBI (86). The team average is only .231, part of the late 60s pitching domination that leads to the mound being lowered in 1969 and the AL adopting the DH in 1973.

- 1967: Trying to emulate the White Sox Hitless Wonders of 1906, the club hangs in the four-team pennant race even though team BA drops even further to .225. However, they fade in the last week to finish 89-73, four behind the Red Sox. The staff leads the league in ERA at 2.45. Joe Horlen wins 19, and lefty Gary Peters, 16. Agee slumps to .234/14/52, and no regular hits over .241.

- 1968: To bolster attendance, Chicago plays nine games, one against each AL foe, in Milwaukee County Stadium, which had been vacated by the Braves after the 1965 season. The Sox win only one Wisconsin game. With the club in ninth place at 34-45, management fires Stanky and calls back Lopez. However, he can lift the Sox only to eighth (67-95).

|

Tommie Agee |

Stanky managed one more major league game. After his White Sox tenure, he returned to his home in Mobile to coach the University of South Alabama baseball team starting in 1969. In June, 1977, he accepted the Texas Rangers job and won his debut. Then, missing his family, he resigned and returned to USA and coached through 1983. His career MLB winning percentage is .518. The field at USA is named for him.

|

In 1923, Wes Schulmerich finished high school/junior college in Portland OR at age 22. (He had missed several years of school working on his family's farm.) A fast 5'11" 200 pounds, he starred in football, baseball, and track. As a result, he was recruited by numerous schools, including Notre Dame. To the end of his life, he kept the letter that Knute Rockne wrote him. Instead, he attended Oregon Agricultural College (today's Oregon State University). In the fall, Wes played FB, LB, and K so well he earned the nickname "Ironhorse" and made All-Coast his last two years. Spring found him roaming the OF and batting well over .300. In fact, he hit .459 his senior year. He also ran a 10.5 100yd dash.

In 1927, after graduating with a degree in business, he turned down a $100-a-game contract to play football for the Frankford (PA) Yellowjackets of the NFL. Instead, his baseball coach got him a job playing semi-pro ball. That led to a contract with the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League, which some considered a third major league. After hitting .328 in 1930, he made the majors with the Boston Braves. In 1933, he was traded to the Phillies. He hit .318 that year, fifth best in the NL. A new manager didn't appreciate his skills, and he was traded again the next season to Cincinnati but didn't play much there, perhaps because he was getting too "chunky." His average for his four NL seasons was .289.

|

In 1935, Wes was sent to Toronto of the International League. Then it was back to Los Angeles where he hit .301. At his request, he was traded to the Portland Beavers in his home area. During this period, he started entertaining fans with clownish behavior. One of his antics cost him his job. When a ball down the RF line went off his glove, fans hooted at him. He laughed back at them. The play cost the Beavers the game. When he returned to the clubhouse afterwards, his severance check was waiting for him.

Playing and managing in towns all over the Northwest, Wes perfected his comedy act. He pantomimed playing tennis and fishing and falling out of the boat. One routine involved getting hauled off the field by a cop only to reappear wearing the policeman's clothes. He would also climb the backstop and hang down (similar to what Jimmy Piersall did years later). At age 39, he finally retired from playing but continued to tour ballparks as an entertainer until he served in the Navy during World War II. Afterwards, he returned to Oregon and worked over the years as a county commissioner, golf course owner, and fishing guide.

In 1984, he was featured in a Sports Illustrated article. However, it was not about his playing career. Instead, the focus was on his lifelong loyalty to the Oregon State teams. According to the article, he had attended every Beaver home football game for 62 years although his years in the service must have interrupted the string. He and his wife and his friend Charles Tharp also made almost all the home baseball and basketball games and track meets. Wes and Charlie never went to nearby Eugene to see OSU play the hated Ducks of Oregon. "Wes and I don't like them, and they don't like us. Walk down the street and they'll throw mud at ya." Tharp admitted to doing the "meanest, nastiest thing" after a 1924 game. After the Ducks won, several of their fans stole his OSU hat. "I stood behind a tree and waited until their car came around the corner. Then I threw an oak branch through their windshield and ran off."

Wes Schulmerich died in 1985 at age 83.

|

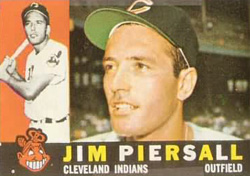

This article might be called "a typical month in the baseball career of CF Jim Piersall." Here are some incidents he was involved in during May/June 1960 while playing with the Cleveland Indians.

- The first occurred during a game against the White Sox in Chicago. While waiting on deck, Piersall got into an argument with home-plate umpire Frank Umont over a strike Umont called on Johnny Temple. When he stepped to the plate, Jim renewed the argument, then stopped and got ready to hit. He cracked Billy Pierce's first delivery over the LF fence.

- The next day, Jim smashed a long drive to CF with two outs. Jim Landis got his glove on the ball but, when he hit the fence, fell back. From his vantage point, Piersall didn't see the ball fall over the fence. So he stopped at 1B, threw his batting helmet toward the dugout, and waited for someone to bring his glove. When he found out what happened, he raced around the bases bareheaded at top speed (which is how he ran out every HR).

|

|

- In Detroit, Piersall provoked the fans, whom he considered the worst in the league. In 1954, playing for Boston, he had made a good catch. When the crowd booed, he showed his teeth. Fans threw paper clips, whisky bottles, and other debris. This time, six years later, he hit a three-run HR in the ninth to put Cleveland ahead. When he went to his CF position for the bottom of the inning, he was greeted with ice cubes and paper clips. (Remember. Detroit is the city that pelted Ducky Medwick with trash in the 1934 World Series.) Jim told umpire Larry Napp the game should be forfeited, but he just laughed. As the game ended, someone threw a firecracker wrapped in wire to make it travel further. It made noise and smoke when it went off.

- The next day, Cleveland was back in Chicago for a DH. In the first game, Piersall on second started squawking at Napp for calls he made on Harvey Kuehn. (Another case of Jimmy going out of his way to provoke umpires.) The second base umpire, Cal Drummond, told him to shut up and, when Piersall whirled on him, threw him out of the game. Once back in the dugout, Jim threw helmets, bats, and gloves on the field because he realized his 15-game hitting streak was over.

- In the nightcap, just as Piersall caught the final out in CF, an orange hit him in the head. So he picked it up and threw it against the giant new exploding scoreboard that owner Bill Veeck had installed. Then he threw the ball too. After the game, Veeck called Piersall and gave him hell. Jim was fined $250. "I deserved it." However, many of his teammates expressed admiration for what he did. "Veeck spent $300,000 on the board," said one player, "but he doesn't spend a dime on the visiting players' dressing room, the worst in the league."

- A week later, Detroit was the opponent again. Tiger manager Jimmy Dykes demanded the umps make Piersall put on his batting helmet in the on-deck circle. So Jim started a shouting match with Dykes. Then he pointed to the LF stands with his bat, a la Babe Ruth. Lo and behold, he hit the first pitch right where he pointed. Jim just stood and laughed. Then as he rounded third, he tipped his hat to Dykes. Expecting to get low-bridged the next time up, Piersall wore a football-type helmet to the plate.

Reference: "A Hero of Many Moods," Sports Illustrated, June 20, 1960

|

Most Watched Event in History

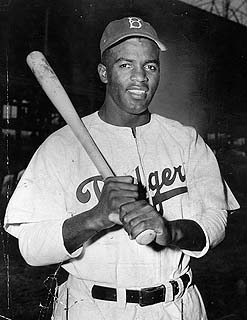

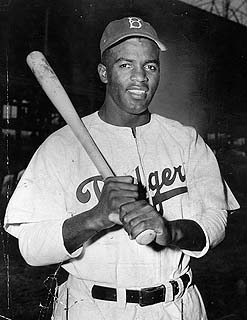

Jackie Robinson

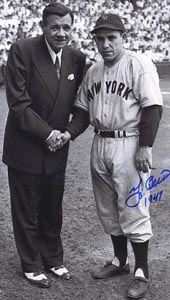

Yogi Berra with Babe Ruth during the 1947 World Series

|

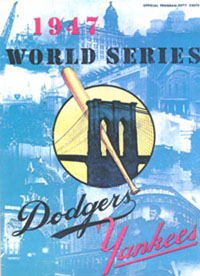

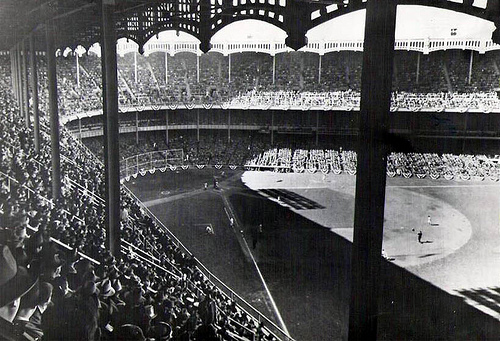

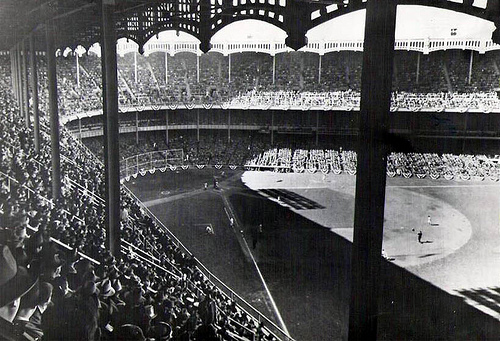

The first game of the 1947 World Series between the Brooklyn Dodgers and the New York Yankees "was seen by more people than any event in history" to that point.

- The largest paid crowd ever to see a World Series game, 73,365, packed Yankee Stadium.

- Approximately 25,000 watched from nearby rooftops.

- The game was the first Fall Classic contest to be televised. NBC's network included New York, Washington, Philadelphia, and Schenectady. Broadcasters estimated that 3.9 million people watched the game, although this is likely an exaggeration. Even so, sports entered a new age that fall.

The prospect of watching the World Series on TV created some interesting news stories.

- About 15% of the TV sets in New York City were in barrooms. One watering hole in Brooklyn installed two sets – one for Dodger fans and one for Yankee fans.

- The Park Avenue Theatre set up a TV set in the lobby so that patrons watching the movie Frieda could check the baseball action.

- The jury for a Kings County trial of a cabdriver accused of rape threatened to walk out because they didn't want to miss the opening game. So the judge called a recess, sent a staff member to purchase a TV, and set it up in his library so that everyone but the defendant could watch the game.

- Asked by reporters whether he would attend the game, President Harry Truman said he didn't have time but would try to catch a few innings on television. A few days later, he gave the first televised presidential address from the White House, asking Americans to make sacrifices to help alleviate the worldwide food shortage that continued after World War II.

The 1947 World Series was also the first one in which an African-American participated. Jackie Robinson broke another color barrier when he stepped in the batter's box in the first inning. With his mother Mallie in the stands after traveling from California, Jackie walked. Then he stole second on rookie C Yogi Berra.

The Series, one of the most interesting ever played, went to the Yankees in seven.

|

Reference: Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson's First Season, Jonathan Eig

|

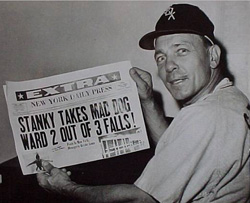

Tim Hurst was a colorful player, manager, and umpire who was often the focus of controversy. He has the dubious distinction of being the only umpire fired by both the National and the American Leagues.

- 1897: By Hurst's seventh season as a National League umpire, he has gained a reputation as a colorful but cantankerous umpire who keeps players n line by hitting them over the head with his mask or pinching them hard. When an irate fan tosses a beer stein at him, Hurst throws it back but hits the wrong fan. Tim is fined $100 and dismissed by the league.

- 1898: In his only year as a ML manager, Hurst is called on to umpire when Bob Emslie is too ill to continue following the first game of a doubleheader between Hurst's St. Louis Browns and Baltimore. Orioles manager Ned Hanlon recommends Hurst since he had already served a stint as an NL arbiter. When the contest ends in a 6-2 Baltimore victory, the crowd cheers "Tiny Tim." At the end of the dismal last-place season, the Browns fire Hurst.

- Hurst referees boxing matches, including the 1899 bout in which Tom Sharkey knocks out Kid McCoy in 10 rounds at the Lenox Athletic Club in New York.

- 1900: The National League rehires Hurst. However, he is barred from working in cities whose club owners "object to having a man of that type associated with their grounds, where ladies and gentlemen watch the games." This specifically means Cincinnati and New York. After the season, Hurst is not rehired by the NL until 1903 when the new American League hires away some NL umps.

|

Tim Hurst |

Ban Johnson

|

- 1903: During the first game of a morning-afternoon doubleheader between the New York Giants and the Brooklyn Superbas, Jimmy Sheckard sticks his bat in front of a throw to second by Giants C Frank Bowerman. Hurst refuses to call interference, causing the Giants to ignore the deflected ball and the runner circling the bases and argue heatedly. Hurst does eject Schekard from the game.

- 1906: In his second year as an AL umpire, Hurst strikes New York Highlanders manager Clark Griffith in the mouth after Griffith accidentally steps on Tim's shoe during a 10-minute argument following a close play. Griffith is ejected, but the league suspends Hurst for five days.

- 1907: The National Police Gazette lists "Honest John" Kelly and Tim Hurst among the greatest boxing referees. Both have umpired in the majors, with Kelly also playing and managing.

- August 3, 1909: After being called out at second by Hurst, Eddie Collins of the homestanding Philadelphia A's argues vehemently, using words like "yellow," "crook," and "blind bat." Hurst turns and spits in Collins' face before teammates pull the two apart. After the game, police battle fans for 20 minutes as Hurst is hit by cushions and bottles. AL president Ban Johnson suspends Hurst indefinitely.

- August 12, 1909: Johnson fires Hurst after investigating the spitting incident. Hurst continues to referee boxing matches.

- June 4, 1915: Hurst dies at age 49.

|

|

Dale Murphy

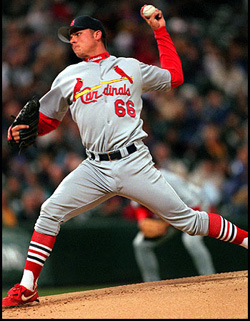

Rick Ankiel

Chuck Knoblauch

|

One of the "One Great Year" features on this site discusses Von McDaniel, whose sensational rookie year excited Cardinal fans in 1957 only to see him forgot how to pitch during the next off-season. Here are some other instances of players who developed a mental block that affected their play.

- Dale Murphy was a promising C with the Atlanta Braves in 1977. During a spring training game, he made several bad throws to second. The next day, when a base runner took off for second, he threw the ball to the OF fence on one hop. Later that season, he twice hit his own P in the back with throws to second. Finally, when he couldn't even return the ball to the P, he moved to the OF where he became an All-Star.

- Steve Gasser was a 19-year-old phenom in the New York Mets farm system. In 1988, pitching at the Class A level, he walked eleven and uncorked seven wild pitches in one inning. Altogether, he walked 21 and threw 13 wild pitches in six innings. He never pitched again.

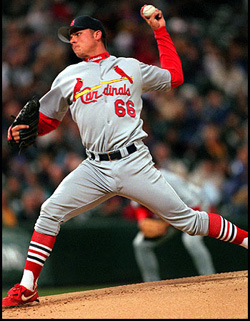

- Rick Ankiel now patrols the OF for the St. Louis Cardinals. However, he began his professional career as a highly promising P who could also hit quite well. He was the 1999 Minor League Player of the Year. With the Cardinals in 2000 at age 21, he went 11-7 and compiled a 4-0 record with a 1.97 ERA in the last month of the season. As a result, he started the first game of the Division Series against Atlanta. In that game and in two others in the playoffs, he walked eleven in four innings, flipped nine wild pitches, most of which were high over the batter's head. Against the Mets, he fired five of his first 20 pitches off the screen behind home plate.

- In 1992, Mets C Mackey Sasser had to pat the ball into his glove several times before lobbing the ball weakly back to the P. Not only did this hangup drive the Mets pitchers crazy, but opposing baserunners took the opportunity to make delayed steals. During one game, Montreal Expos players counted Sasser's false starts with the ball, then cheered sarcastically when he threw the ball to the mound.

- Chuck Knoblauch made only eight errors during the entire 1996 season at 2B for Minnesota. He won a Golden Glove in 1997. Then, with the Yankees in 1999, he committed 26 errors. 14 were throwing errors, most of which were on routine tosses to first.

- Knoblauch followed in the footsteps of another 2B who developed the yips throwing to first. In fact, the problem was labeled Steve Sax Disease in "honor" of the Dodger who had thirty errors by mid-August in 1983.

- RHP Steve Blass won 15 games for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1971 with a 2.85 ERA. He added victories in games 3 and 7 of the World Series. Then in 1972 he went 19-8 with a 2.48 ERA. His career average was less than three walks per nine innings. During spring training in 1973, Blass walked 25 men in 14 innings. That season he won only three while losing nine and saw his ERA balloon to 9.85. He walked 84 in 88+ innings. That ended his baseball career.

Reference: "Bring the Pain," David Shields, Elysian Fields Quarterly, Winter 2004 |

|

|