|

CONTENTS

World Series Lost by a Straw Hat

What's He Clapping About?

"Only Time I Saw Durocher Backed Down"

Ugly No-Hitter

MacPhail's Flying Circus

Bases Loaded Intentional Walks

A Pebble Helps a Rock

Rube Returns to Louisville

Tragedy at the Polo Grounds

Stan's 3,000th

Baseball

Vignettes Index

Baseball Magazine

Golden

Rankings Home

Top of Page

|

World Series Lost by a Straw Hat

After taking two of three games from the Boston Pilgrims, the 1905 Philadelphia Athletics left on the train for New York to meet the Highlanders.

- Connie Mack's A's led the AL by 4.5 games over the Chicago White Sox.

- Fans in the City of Brotherly Love were already talking about a matchup with with the New York Giants, who were running away with the NL pennant.

- It was Giants manager John McGraw who refused to play the AL champion A's after the 1904 season because he believed the rival circuit was no better than a minor league. As a result, the World Series of 1903 was the only one that had been played since the two leagues reached a truce in which they respected each others' contracts.

1905 Philadelphia Athletics with their manager, Connie Mack (in civilian clothes in the center);

Rube Waddell is kneeling just to the left of Mack.

The main cog in the A's machine was their eccentric left-handed pitcher.

- Rube Waddell had already won 27 games with almost a month left in the season.

- Fans salivated at the thought of several World Series confrontations between Rube and Giants ace Christy Mathewson.

RHP Andy Coakley had won the second game in Beantown.

- Andy asked Mack for permission to visit his family in Providence RI the next day.

- Connie agreed, instructing Coakley to meet the team when they changed trains in Providence on their way to The Big Apple.

Waddell was an overgrown child who loved to play pranks.

- Straw hats were highly popular with men in those days. However, custom dictated that they be worn between Decoration Day (May 30) and Labor Day.

- Rube made it his duty to enforce the straw hat ban by putting his fist through the top of any straw hat worn by an A's player or official after the cutoff date.

As the Athletics detrained at Providence, Rube saw a site that triggered the enforcer in him.

- There was the nattily dressed Coakley on the platform with the bag containing his gear over his shoulder and a straw hat with a red ribbon on his noggin.

- Weighing nearly 200 lbs, Rube rushed at his teammate. As Andy swung away to avoid his assailant, the spikes in his bag struck Rube in the chin. The dazed lefty thought Coakley had punched him. His fun-loving mood turned to anger.

- The other players hurried to get between the two pitchers, but Rube easily pushed the first few aside before enough piled on to make him tumble over suitcases onto the platform, landing on his left shoulder.

The players calmed Rube down, and the team boarded the train to New York.

- Rube began to feel the soreness in his shoulder as he sat next to an open window.

- Two days later, he told Mack that he had felt a "click" in his shoulder while shaving.

- Mack, a former C, grabbed a mitt and led Waddell outside to see if he could throw the ball. He couldn't. His shoulder was hurt more seriously than first thought.

By September 11, newspapers reported that Rube would be out of action at least a week.

- Rumors spread quickly that Waddell was not hurt at all. Instead, the theory went, gamblers were intent on keeping Rube out of the World Series.

- Connie deflected all such talk. Besides, he had a pennant to win without his best P.

- By September 26, the White Sox caught them. However, the A's beat Chicago two of three in a crucial series and held on to win by two games.

- Mack tried Rube in relief twice the last several weeks. In the first appearance, he faced only one batter who lined out hard to CF. In the second, Rube pitched well from the third through the seventh only to surrender four in the eighth. There was no way he could pitch at peak efficiency for an entire game against the mighty Giants.

Without their star, the A's fell to McGraw's boys in five games. Philly fans, to their dying days, believed their heroes would have won if Rube could've pitched.

John McGraw and Connie Mack at 1905 World Series Reference: Rube Waddell, Alan H. Levy (2000)

Top of Page

|

Connie Mack

Rube Waddell

Andy Coakley

|

What's He Clapping About?

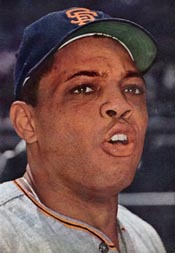

Whitey Ford

Willie Mays

Mickey Mantle

|

The 1961 All Star Game was played at San Francisco's Candlestick Park. It is best remembered for the balk committed by Stu Miller of the Giants in the top of the ninth when the wind blew so hard, he lost his balance on the rubber. But an amusing incident occurred in the first inning that was not understood at the time.

- Whitey Ford of the Yankees started for the AL. After getting two ground outs, he struck out hometown hero Willie Mays. That caused Mickey Mantle to jump and applaud as he ran in from CF.

- As Ford walked past Mays, Willie asked, "What's that crazy bastard clapping about?" Ford gave no explanation, knowing that Willie was upset that Mantle seemed to be showing him up. Did Mickey's glee stem from the perennial debate in those days as to who was the better CF?

Willie didn't understand that Mickey's display was not directed at Willie and came about as a result of an incident the night before.

- The Giants owner, Horace Stoneham, as All-Star game host, had arranged for Mantle and Ford to play golf the day before at the exclusive Olympic Country Club. However, neither Yankee had brought golf equipment and had to purchase some. Since the pro shop didn't accept cash, they charged their purchases to Stoneham with the intent of paying him back at the ball park the next day.

- As it turned out, the three met at a party that night. Ford tried to pay what he owed, but Stoneham stopped him by proposing a bet. If Whitey retired Mays the first time he faced him, both debts would be forgiven. However, if Mays got a hit, the payments would double to $800 each. Horace felt confident since Willie had gone 6-for-7 off Ford in All-Star competition.

- Against Mickey's advice, Whitey took the challenge. The teammates then did what they often did – party the night away and arrive at the ball park in less than prime condition.

- There is another amusing aspect to the incident apart from the bet. Mays socked Whitey's first pitch, a curve, over 400' but foul. When Whitey tried another bender, Willie hit an even louder foul. Ford decided the only way to win the bet was to resort to trickery. So he spit on his pitching hand and pretended to wipe it off on his shirt. This time, his curve ball started at Mays's head before dropping "from his chin to his knees," as Whitey described it. Umpire Stan Landes called him out.

- When Mantle reached the dugout, his buddy pointed out that Willie didn't appreciate Mick's reaction. "It didn't dawn on me right away how it must have looked to Willie and the crowd," said Mantle much later. "It looked as if I was all tickled about Mays striking out because of the big rivalry. When Whitey mentioned my reaction, I slapped my forehead: How could I? What a dumb thing."

Whitey later explained the entire incident to Mays, who laughed when he learned the real reason Mantle had jumped for joy.

Reference: The Baseball Codes: The Unwritten Rules of America's Pastime, Jason Turbow

Top of Page |

|

"Only Time I Saw Durocher Backed Down"

Those are the words of announcer Red Barber in his book 1947: When All Hell Broke Loose in Baseball. Red was referring to an incident that occurred in 1943 at the height of World War II.

- Leo Durocher had managed the Dodgers since the 1939 season. Brooklyn won the NL pennant in 1941 and then lost by two games to the Cardinals in '42 despite winning 104 games.

- The peripatetic Bobo Newsom pitched for Brooklyn in '43. On Friday night, July 9, the Dodgers beat the Pirates 7-6 at Ebbets Field on a squeeze bunt by Billy Herman in the 10th inning. Afterwards, Durocher was still mad at a pitch his starter, peripatetic Bobo Newsom, for a delivery that got past rookie C Bobby Bragan to score a Pittsburgh run. After confronting Newsom in the clubhouse, Leo told P Hugh Casey, on leave from the Navy, that Newsom was trying to "show up" Bragan by throwing a spitter when Bobby had called for a fastball. Durocher suspended Newsom indefinitely and warned that, if GM Branch Rickey backed him, the suspension would be permanent.

- Tim Cohane, a writer for the New York World-Telegram, was present in Leo's office when he made his remark to Casey. Durocher then told Cohane, without further explanation, that he had suspended Newsom, thus implying that the spitball was the reason. Tim not only reported the comment in his article on the game but told other scribes about Bobo's suspension.

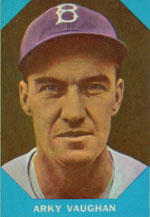

- The next day, Barber was sitting in Durocher's office during batting practice when a furious Arky Vsaughan barged in. The Hall-of-Fame-bound SS said: "I just heard what's in the papers about what you said about Newsom. If that's so, here's my uniform!" Leo had failed to inform the team of the suspension before they read about in the papers.

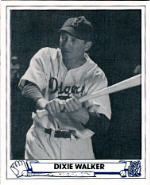

- Dixie Walker yelled from outside the door, "If that boy takes off his uniform, then you've got mine too." With his ball club in rebellion, Leo denied making the remark that Cohane quoted but refused to lift Bobo's suspension.

- At 2:30, when the game against the Pirates was scheduled to start, the only Brooklyn players on the field were P Curt Davis and Bragan. Ten minutes later, after Durocher pleaded with the others to take the field, all the Dodgers appeared with the exception of Vaughan, who sat with Newsom in the grandstand near the Brooklyn bullpen in RF. During the game, GM Branch Rickey summoned Vaughan to his office. After the conference, Arky put on his uniform and appeared on the Dodger bench. He was not suspended.

The 2nd-place Dodgers took out their wrath on the 3rd-place Pirates, scoring 10 in the first and another 10 in the fourth in the 23-6 romp.

- In a press conference held after the game, Durocher explained that he had suspended Newsom for three days for "insubordination." He also claimed the players had forgotten all about their brief revolt, which was unique in Ebbets Field history. Leo explained further:

Newsom was always questioning my judgment in clubhouse meetings before each game. We never agreed on how to pitch to certain batters. There was always a clash of ideas. The suspension resulted from my questioning him on how he had pitched to Vince DiMaggio yesterday, when DiMaggio doubled to left. Newsom said, "high and inside." I said, "How far inside?" "This far," Newsome said, gesturing. I told him it wasn't far enough inside and he virtually told me I was a liar. Nobody can talk to me like that as long as I'm managing the club and that goes for all the players.

- The Associated Press article on July 10 contained this information.

During the third inning [of the July 8 game] C Bragan missed a called third strike that would have retired the Pirates. Instead a Pittsburgh run scored. Newsom, who was seeking his 10th win of the year, was removed for a pinchitter in the seventh and in the eighth was chased off the bench by Umpire Goetz for abusive remarks.

In the clubhouse after the game, it was reported Newsom and Bragan got into a discussion over whether the missed third strike had been a spitter or knuckler or merely a fast ball. Newsom insisted it was a fast ball, but most of the Dodgers expressed the opinion it was a screwy sort of pitch, possibly a spitter. Durocher was irked that Newsom had failed to tip off Bragan to watch for a spitter.

- According to Barber's book written 39 years later, Leo talked on the phone before the game to Cohane who was at home on Saturday, his day off. The skipper accused Cohane of fomenting trouble on the Dodgers over something Leo hadn't said. Cohane said he would be at Ebbets Field the next day and called GM Branch Rickey to demand a meeting with Durocher in the clubhouse before the entire squad. Rickey tried to talk Cohane out of it, but the indignant writer said Leo had called him a liar.

- The next day (July 11), the players forsook batting practice before the Sunday DH to attend the meeting. Other writers attended to support their colleague. Cohane related his conversation with Leo after Friday's game.

- According to Ted Meier's AP story on July 12: "Durocher confirmed Cohane's story but insisted his remarks about Bragan were directed only to Casey, adding 'perhaps I made a mistake not telling Cohane that I was suspending Newsom for general insubordination.'"

- According to Meier, Newsom then asked Leo: "Why did you deny to the players here Saturday that you said I was trying to show up Bragan and why did you tell Casey I was?" "Well," replied Durocher, "you know how you talk to a ball player. I told you you were suspended for the season and you got only three days."

- Meier continued: "... future flareups can be expected unless Durocher succeeds in restoring harmony. New York baseball writers agreed that 'there are strong reasons to believe Leo will not last the season as manager.'"

The writers were dead wrong.

- Faced with a rift between his manager and his ball club, Rickey stood solidly behind Durocher and traded Newsom to the Browns.

- Leo continued as Dodger manager until spring training of 1947 when Commissioner Happy Chandler suspended him for the season because of association with gamblers.

References: 1947: When All Hell Broke Loose in Baseball, Red Barber

Branch Rickey: Baseball's Ferocious Gentleman, Lee Lowenfish |

Red Barber

Leo Durocher

Bobo Newsom

Bobby Bragan

Branch Rickey

Tim Cohane

|

| |

When Pittsburgh P Dock Ellis, visiting friends in Los Angeles on Friday, June 12, 1970, awoke around noon, he thought the Pirates had the day off.

- So he took three hits of Purple Haze LSD.

- An hour later, he found out from the newspaper that he was the starting P in the first game of a DH in San Diego that night.

- So he booked a flight, arriving in time for the game.

- Dock says he also took about a half dozen amphetamines ("greenies") before taking the mound.

- In 1984, when Ellis came clean about his drug use before the 1970 game, he said: "I can only remember bits and pieces of the game. I was psyched. I had a feeling of euphoria. I was zeroed in on the catcher's glove, but I didn't hit the glove too much. I remember hitting a batter, and the bases were loaded two or three times."

- Dock also recalled: "There were times when the ball was hit back at me, I jumped because I thought it was coming fast, but the ball was coming slow. The third baseman came by and grabbed the ball, threw somebody out. I never caught a ball from the catcher without two hands, because I thought that was a big ol' ball! And then sometimes it looks small. One time I covered first base, and I caught the ball and I tagged the base, all in one motion and I said, 'Oh, I just made a touchdown.'"

- He also imagined Jimi Hendrix in the batter's box swinging his guitar and then-president Richard Nixon calling balls and strikes.

Unfortunately for clean-living advocates, Ellis pitched a no-hitter that evening in San Diego!

- He walked eight and hit one.

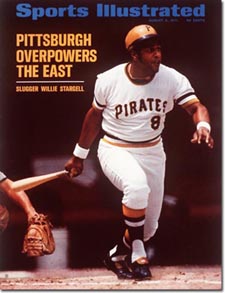

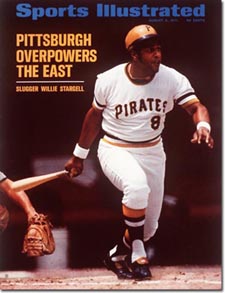

- Two solo HR by LF Willie Stargell produced the only runs of the game.

- In retrospect, it's amazing that Ellis didn't hit more batters or get injured himself.

- Teammates say that Dock, ignoring superstition, commented on the bench between innings that he was pitching a no-hitter.

- As was the Pirates' custom at the time, Ellis was forced to keep track of the pitch count for the nightcap of the DH. There is no report on the accuracy of his work.

|

Dock Ellis

Willie Stargell

|

Dock is remembered for other colorful antics.

- In 1972, Dock showed up drunk to Riverfront Stadium, where he was stopped by a security guard, who asked to see Ellis' player ID card. With a half-finished jug of wine in one hand, the P took a swing at the guard before being maced and charged with disorderly conduct.

- In 1974, angered by the swagger of the Cincinnati Reds before the game, he tried to hit every batter he faced. He plunked the first three, walked the fourth, and threw at Johnny Bench's head twice before he was removed. Dock later admitted he took amphetamines before this game also.

- In the late 70s, he wore curlers in pregame warmups after baseball officials complained about his hair.

Eventually, Dock cleaned up his life and, after retiring in 1979 with a 138-119 record, worked as a drug counselor in California.

- Indie rock singer Barbara Manning wrote the song "Dock Ellis" in 1993 that recounts his no-hitter. Following Dock's death in December 2008 at age 53, Todd Snider wrote another tune, "America's Favorite Pastime," about the no-hitter.

- In November 2009, the web site The Slanch Report started an online petition demanding that MLB search its archives and find a video of Ellis's no-hitter. It is not certain that such a video exists since games were not routinely telecast in 1970. It is also not certain that the MLB office would want to release such a video even if it exists.

|

Top of Page |

Reference: "No-Hitters Are Not Always Pretty," George Vass, Baseball Digest, May/June 2010

|

|

Larry MacPhail |

In

January 1945, Del Webb and Dan Topping bought the New York Yankees from Jacob Ruppert's estate. They paid 2.8 million

for the team, the stadium, and the farm system. They immediately replaced Ed Barrow, the GM since 1920, with Larry

MacPhail, newly discharged from the Army. They also gave MacPhail a third of the club. Larry had been an innovative but controversial GM for the Reds (1934-37) and Dodgers (1938-42). These were some of his innovations and achievements.

- As

owner of the Columbus club in Branch Rickey's Cardinal farm system,

outdrew the parent club 310,000 to 279,000 in 1932

- First

night game in the major leagues (Cincinnati,

1935) and the first night game in Brooklyn (1938)

- First

televised game (1939)

- Began

the upgrade of the Reds that led to pennants in 1939 and 1940

- Put

all Dodger games

on the radio with Red Barber behind the mike (MacPhail had first hired Barber in Cincy)

- Outdrew

the Yankees and Giants in attendance in 1939 (960,000 to

860,000 to 700,000)

- Hired Leo Durocher who managed Brooklyn to the 1941 pennant, the first in Flatbush in 21 years

|

Immediately

setting out to change the culture of the Yankees,

MacPhail:

- Installed

lights at Yankee Stadium (first night game May 28, 1946).

- Engaged

Mel Allen to broadcast all games on the radio.

- Forced

the resignations of three managers in 1946, including future Hall

of Famers Joe McCarthy and Bill Dickey.

- Hired

Bucky Harris as manager for 1947, when the Yankees

won the World Series.

The

players' biggest complaint was what they called "McPhail's

Flying Circus." Larry loved airplanes and tried

to eliminate train travel as much as possible. However, players missed

the card games and camaraderie of rail travel. Some were afraid of

flying while others didn't appreciate wasting hours in airports waiting

for weather to clear. Some players arranged their own train travel.

Even more started boycotting the charity events and dinners MacPhail

wanted to fly them to. Eventually, he relented and allowed them to

travel by train again. However, he reminded them that they were required

by their contracts to participate in club promotions.

In

1947, in his unrelenting quest for PR, MacPhail hired

a newsreel crew to take pictures of the Yankees

posing with soldiers before a home game. However, the crew arrived

after batting practice had started. Joe DiMaggio,

among others, told them to get lost. Larry fined

two players $50 each and DiMag $100. However, fans

all over the country rallied to pay the Yankee Clipper's

fine. For example, a Buffalo Boys Club sent $1.03 in pennies with

a promise to send more later.

MacPhail's

antics didn't sit well with Topping and Webb.

When Larry got drunk at the 1947 World Series celebration,

unleashed a barrage of insults, slugged a reporter, and announced

his resignation, his co-owners bought him out and made George

Weiss the GM.

Top of Page

|

Bases

Loaded Intentional Walks

Baseball

Digest August 2007: "According to one source, the intentional

walk dates as far back as June 27, 1870 when George Wright

of the Cincinnati Red Stockings

was walked on purpose in a game against the Washington Olympics.

At the time, Wright was considered the best baseball

player in the country."

In

another

Baseball Digest article, Jerome Holtzman

(Official Historian of MLB and creator of the Save rule), states that

the first time an intentional walk was issued was 1896 when the New

York Giants walked Chicago

slugger Jimmy Ryan. P Jouett Meekin

then struck out weak-hitting George Decker to end

the game.

As

early as 1913, Ban Johnson, president of the American

League, and others wanted to eliminate the intentional walk. The Major

League Rules Committee discussed such an action in 1926 because the

institution of the catcher's balk (requiring the catcher to be inside

the catcher's box when the pitch was delivered) had not ended the

strategy. However, the committee took no action. It should also be

pointed out that MLB did not keep track of intentional walks in its

box scores until 1955. So it is impossible to know how many times

sluggers like Babe Ruth, Rogers Hornsby,

or Jimmy Foxx were walked intentionally. Occasionally,

newspaper reports mentioned the strategy.

In

the article cited above, Holtzman lists three occasions

since 1901 when a batter was intentionally walked with the bases

loaded.

- May

23, 1901: Nap Lajoie of the Philadelphia

A's by Clark Griffith of the Chicago

White Sox

Chicago led 11-7 in the ninth. To avoid a tying grand slam, Griffith, Sox manager working

in relief, walked Nap with no outs. The strategy

worked as the next three batters hit groundouts, and Chicago won 11-10.

- July

23, 1944: Bill Nicholson of the Chicago

Cubs by Andy "Swede" Hansen of the New York Giants

Nicholson had hit three HRS in the first game of the doubleheader at the Polo

Grounds (with its short left and right field porches) and

swatted another in the seventh inning of the nightcap. When Big

Bill came up with the bases full in the eighth, the Giants led 10-7. To avoid a grand slam, manager Mel Ott ordered the walk. Then Andy Pafko flied out to

end the inning. The Giants won 12-10.

- May

28, 1998: Barry Bonds of the San

Francisco Giants by Greg Olson of the Arizona Diamondbacks (in their first year of existence)

Manager Buck Showalter, to preserve an 8-6 lead with

two outs in the ninth, ordered the walk to the slugger who has

the most intentional passes in a season (120 in 2004) and a career

(688 through the 2007 season, which is almost 400 ahead of second

place Hank Aaron). The next batter, Brent

Mayne, lined out to end the one-run victory.

|

Nap Lajoie

Bill Nicholson

Top of Page |

baseball-almanac.com

also lists a 1881 bases-loaded intentional walk to Abner Dalrymple

of the Chicago White Stockings.

The following explanation is given.

Abner

Dalrymple, August 2, 1881 - the Bisons

were were down 5-0 versus the White

Stockings in the eighth inning. The Chicago

Tribune described the moment with, "In the eighth the

bases were filled, and nobody out, on successive hits by (Fred)

Goldsmith, (Silver) Flint,

and (Joe) Quest, and (Jack)

Lynch was so afraid of Dalrymple

that he gave him his base on balls and brought Goldsmith

in with the gift."

|

Oh,

little pebble! How mighty thou art!

In

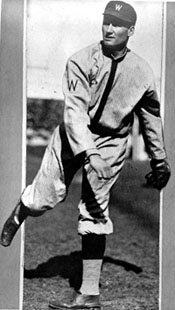

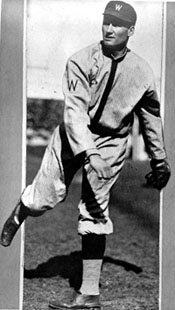

his 18th season with Washington, Walter Johnson finally got to pitch in the World Series after the Senators edged the mighty Yankees by two games to win the 1924 pennant. The "Big Train"

pitched well in Game One in his home park, striking out 12, but lost

to the New York Giants in 12 innings, 4-3. Then,

with the Series tied two games each, he lost at the Polo Grounds 6-2.

It appeared he had missed his last chance to win a World Series game

since the Senators couldn't be expected to win their

second pennant any time soon. However, the Nationals (as they were also called) edged John McGraw's Giants 2-1 in Game Six to set up the decisive finale. Both runs were driven

in on a fifth-inning single by player-manager Bucky Harris.

Bucky resorted to a trick he had used in Detroit in the late stages of the pennant race. He announced he would start

right-hander Curley Ogden, which induced McGraw to start his lineup against right-handers. However, after Ogden struck out leadoff hitter 3B Freddie Lindstrom, Harris came in from his 2B position and called left-handed George

Mogridge, who pitched scoreless ball into the sixth. In the

meantime, Harris hit a long fly that just dropped

over the temporary bleachers in left to give the Nats a 1-0 lead going into the sixth.

The

visitors struck for three as McGraw pulled out some

strategy of his own. After Ross Youngs walked, John called for a hit-and-run on a 3-1 pitch, and George Kelly slapped a single to left to send Youngs to third. McGraw then sent right-handed Irish Meusel to bat for left-handed Bill Terry. This caused Harris to replace Mogridge with righty Firpo Marberry. Meusel hit a SF to tie the game. A single and two

errors plated two more runs to the dismay of the 31,667 fans.

As

the fall shadows lengthened, Giant starter Virgil

Barnes continued his mastery. In the bottom of the eighth,

though, fate smiled on the home team. With one out, PH Nemo

Leibold doubled and Muddy Ruel singled him

to third. Bennie Tate, pinch hitting for Marberry,

walked to load the sacks. However, Earl McNeely flied

out. Then occurred one of the pivotal plays in World Series history. Harris hit a high bounder over Lindstrom's

head to tie the game.

Who

strode to the mound to start the ninth but "the king of pitchers"

(according to the New York Times). However, the move didn't

seem so smart when 2B Frank Frisch tripled to deep

CF with one out. But after intentionally walking Youngs, Walter struck out Kelly –

who had homered off him in Game 5 – and induced Meusel to ground out.

In

the bottom of the frame, a single and error excited the Griffith Stadium

fans only to have hope dashed by a double play. The Senators returned the favor in the top of the tenth, turning a DP on C Hank

Gowdy. In the bottom of the 10th, Johnson swatted a long fly to left center that was caught a few feet short

of the bleachers.

The Old Master had to pitch out of trouble again in the

eleventh. PH Heinie Groh's single and a bunt put

a man on second with one out. But Johnson struck

out Frisch and, after walking Youngs intentionally again, fanned Kelly once more. The Senators got the winning run to second when Goose

Goslin doubled with two outs but Ozzie Bluege grounded out.

Meusel led off the 12th with a single, but Johnson mowed

down the next three to set the stage for one of the most dramatic

endings in World Series history. With one out, Ruel lofted a foul ball behind the plate, but Gowdy tripped

on his mask and missed it. Given new life, Muddy doubled over third. Johnson hit for himself and grounded

to short but Travis Jackson booted it, Ruel holding second. McNeely then created pandemonium

by hitting a bounder that hit a pebble and jumped over Lindstrom to bring in the winning run that gave old Walt and

the Senators their first World Series victory. The

crowd invaded the field "like college boys after the victory

of their football team." A crowd estimated at 100,000 celebrated

the rest of the evening through the streets of the Capital.

The Senators amazed the baseball world by repeating as

champions the next season. After losing two but winning the seventh

game in 1924, Johnson reversed that outcome the next

year. But that's a story for a future Vignette.

|

Walter Johnson

John McGraw

Bucky Harris

Top of Page |

|

Rube

Returns to Louisville

Rube Waddell

Fred Clarke

Honus Wagner

|

It

will take many of these features to tell all the interesting stories

about Rube

Waddell – yarns about his pitching as well as tales

of his off-the-field shenanigans. Both aspects came to bear in the

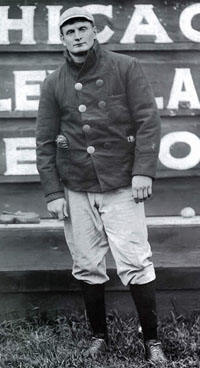

month he spent with the Louisville Colonels of the National League at the end of the 1899 season.

Louisville's

26-year-old player/manager Fred

Clarke didn't know how he would handle Rube in his second stint with the club. Waddell had pitched

briefly for the Colonels at the end of 1897. He had clashed repeatedly with his manager and

was traded to Detroit in the off-season. The Louisville newspapers were agog over the dazzling

record Rube had compiled at Columbus of the Western League (30 wins!). The Colonels also boasted another future Hall of Famer: Honus

Wagner (who played OF that year instead of the SS position

he starred at later).

Rube joined the team for a trip to Baltimore to take on

the Orioles. Clarke tossed his new

southpaw right into the fire on September 12. Rube gave up only two runs in eight innings. The Colonels rallied in the ninth to tie. Then the first Oriole batter in the bottom of the frame tripled. Looking on from LF, Clarke thought: "Let's see what he does now." The next batter was

none other than the great Willie

Keeler. He popped to short. Up came John

McGraw, who also popped to short and the runner was doubled

up. In the top of the tenth, Louisville scored a run but two errors let Baltimore tie again.

After a scoreless eleventh, the visitors scored two in the 12th. Rube set down the Orioles 1-2-3 for the victory. On September

15, Rube won against the Orioles again, this time in relief.

In

Chicago, Waddell was matched against Clark

Griffith, who was 21-12 at the time. Rube struck out 13, an all-time nine-inning record at that point, in a

6-1 win. In the second inning, Rube showboated. He

intentionally walked three batters, then struck out the next three.

Several times he dispatched his C to the press box to find out if

he had the record yet. When he stuck out the last batter, Rube danced a Highland Fling from the mound to the dugout to the delight

of the home crowd. After five wins and a save, Rube finally lost on September 29 against the St.

Louis Browns (a National League team in the 1890s).

Rube's

road roommate, Tommy Leach, said, "He was just

an overgrown boy. It was a riot." On a day off in Louisville, Rube collected a flock of geese, whom he trained

to skip rope, with him on one end of the rope and one of the geese

on the other. He brought the flock to the ballpark one day for a pre-game

show.

Eventually, Rube compiled a 7-2 record, the other loss coming

to Chicago in a game called after six because of

darkness. For the final game of the season, in Pittsburgh, Rube promised he would beat the Steel Town gang for his family, who made

the trip from nearby Bradford PA. Rube was all business,

mowing down the Pirates. As he walked to the mound

one inning, an egg thrown from the stands hit him in the head. He

responded by ordering his outfielders to leave the field. When told

by the umps that all fielders besides the C must be in the field of

play, Rube told the OF, including boss Clarke,

to stand right behind the infielders. Waddell promptly

struck out the side, throwing even harder than Clarke had ever seen him fire. The Colonels won, 4-1, to finish in ninth place. However, Rube's

combined season record for Grand Rapids, Columbus,

and Louisville was 37-12!

|

|

Tragedy

at the Polo Grounds

The

Cleveland News called Ray Chapman

the "greatest shortstop, that is, considering all-around

ability, batting, throwing, base-running, bunting, fielding

and ground covering ability, to mention nothing of his fight,

spirit and conscientiousness, ever to wear a Cleveland

uniform." In

1915, the Chicago White Sox

tried to acquire Chapman from the Indians

but had to settle for Shoeless Joe Jackson

instead.

Before

the 1920 season, newlywed Chapman considered

retirement but decided to play one more year to help his teammate

Tris Speaker, the new manager. Ray

proceeded to have one of the best seasons of his career. As

of Monday, August 16, as the Indians began

a four-game series at the Polo Grounds, which the Yankees

shared with the Giants

while awaiting construction of Yankee Stadium, Chapman's

statistics read: .304, 97 R, 52 W, 27 2B, 49 RBI.

|

|

Carl Mays |

Cleveland

was tied for first with the White

Sox, the defending AL champs who had lost to

Cincinnati in

the controversial 1919 World Series. The Yankees

trailed the co-leaders by 1/2 game. The afternoon was rainy

and dark. Right-hander Carl Mays, a surly individual

unpopular with teammates as well as opponents, threw underhanded

and liked to pitch batters tight. Right-hand hitting Chapman

crowded the plate but jumped back on inside pitches. The weather,

pitching style, and batter's stance combined for tragedy.

The

visitors led 3-0 when Chapman led off the fifth.

On a 1-1 count, Mays caught Chapman

shifting his back foot slightly and interpreted that as a sign

that Ray planned to drop a bunt down the first

base line. So Carl threw his submarine fastball

at the inside corner. The ball sailed up and in. Babe

Ruth said he could hear the sound of the ball hitting

Ray's head out in RF. Sportswriter Fred

Lieb in the press box 50 feet behind the umpire heard

a "sickening thud." The ball rolled between the mound

and the first base line. Mays, thinking it

hit the bat, threw to first. 1B Wally Pipp

started to throw the ball around the infield when he saw Chapman

on his knees in the batter's box, blood streaming from his left

ear. C Muddy Ruel tried to catch Ben

as he sagged. Umpire Tommy Connolly ran toward

the stands calling for a doctor. Speaker rushed

over from the on-deck circle. The Yankee

team doctor applied ice and revived Chapman,

who walked on his own toward the clubhouse in CF but sagged

again near 2B. Two teammates grabbed him and carried him on

their shoulders the rest of the way.

|

Mays

showed the ball to Connolly, claiming a rough spot

on the surface caused the pitch to swerve more than he intended. After

the game, he also said the ball was slippery from the rain. 1920 was

the first year of the ban on spitballs, shineballs, and other doctored

pitches. However, AL president Ban Johnson, concerned

about the added expense from removing discolored baseballs from play,

had ordered umpires to "keep the balls in the games as much as

possible, except those which were dangerous."

The

teams finished the game, a 4-3 Indian victory. Afterwards,

Yankee skipper Miller

Huggins brought Mays to the nearest police

station to file a report on the incident. Chapman

had been taken to St. Lawrence Hospital where doctors made a three-inch

incision in the base of his skull. They found a ruptured lateral sinus

and a great deal of clotted blood. They removed a small piece of his

skull. His pregnant wife got to New York as quickly as possible, but

her husband died early the next morning before she arrived.

Players

all around the league, with the most vociferous being Ty Cobb

(who had had run-ins with Mays), demanded that the

beanballer be banned from baseball. Mays said, "I

would give anything if I could undo what has happened." Witnesses

agreed that Chapman didn't move and almost certainly

didn't see the ball. However, several Indians warned

Mays not to come to Cleveland again, and Huggins

left Mays home when the Yankees

visited in September. The New York Times demanded that batting

helmets be required. Johnson rescinded his order

to keep balls in play as long as possible.

After

the August 17 game was postponed because of the tragedy, the teams

split the remaining two games of the series. After dropping 7 of the

next 9 games, the Indians rallied to win their first

pennant by two games over the White

Sox, whose momentum was stopped the last week of the

season by the revelations of a Chicago grand jury's investigation

into the previous World Series. Cleveland then defeated

the Brooklyn Dodgers

5-games-to-2 in the World Series.

Mays

ended the 1920 season with 27 wins – a total he attained again

the next year. In the 1921 World Series against the Giants,

he hurled three complete games without allowing a walk but was charged

with two losses as the Yankees

lost, 5 games to 3. (Some baseball writers and insiders suspected

Mays and others of throwing the Series, but that's

a story for another time.)

Chapman's

widow Kathleen gave birth to a daughter on February

27, 1921. Once an avid fan, she never attended another game. On April

21, 1928, remarried and living in Los Angeles, she died after swallowing

a poisonous fluid. Her family insisted the death was an accident and

not suicide, although they admitted she had been treated for a nervous

breakdown. Her mother took over care of the daughter who died a year

later during a measles epidemic.

Reference:

Deadball

Stars of the American League, The Society for American Baseball

Research, 2006 |

|

Stan Musial

Fred Hutchinsen

Musial's 3,000th Hit

|

Stan "The Man" Musial entered the 1958 season needing only 43 hits to reach the magic 3,000 mark. At that time, only seven players had achieved the milestone. The latest was Paul Waner of the Pirates, a boyhood idol of Musial, who grew up in Donora PA.

Before the season, Stan estimated he would reach 3,000 in late May. However, he got off to a sizzling start to accelerate the timetable.

- On Sunday, May 11, Stan pounded out five hits in the DH sweep of the Cubs in St. Louis.

- That put him at 2,998 and raised his average to .494.

Thanks to some odd scheduling, the Cards followed the Cubs to Chicago for a two-game series at Wrigley Field before returning to Sportsman's Park.

- Stan preferred to break the record at home. But just in case he got #3,000 in Chicago, his wife, Lil, and several friends made the trip to the Windy City.

- On Monday, May 12, Stan doubled in four trips to the plate. He was only one away.

- Manager Fred Hutchinsen called Stan in his hotel room that night to tell him that he would use him the next day only as a pinch-hitter if needed. As Hutch told a reporter: "I just hate to see the guy get the big one here before 3,000 or 4,000 fans when his home fans can have the chance a day later."

Stan started the Tuesday game sunbathing in the right field bullpen as 5,692 watched the Cards try for their sixth straight after starting the season 3-14.

- The Cubs nursed a 3-1 lead into the top of the sixth.

- RF Gene Green doubled but remained at second as C Hal Smith grounded out.

- Next in the order was P Sam Jones.

Hutchinson called for Stan to pinch hit. The sparse crowd made lots of noise as Musial stepped in against RHP Moe Drabowsky.

- After taking a ball, Stan fouled off the next two pitches. Then another wide one made it 2-2.

- Mo threw a breaking ball outside which Stan swatted down the LF line for an RBI double.

- Umpire Frank Dascoli retrieved the ball and gave it to Stan.

- Hutchinson came out to shake The Man's hand and replace him with a pinch runner, Frank Barnes.

- As Stan left the field, he kissed his wife sitting behind the Cardinal dugout and went into the clubhouse.

- Most of the media left the game and converged on the clubhouse to interview and get pictures of Stan.

- Later, Hutch came into the clubhouse and surprised Stan by apologizing for having to use him as a pinch-hitter. "I'm sorry. I know you wanted to get it in St. Louis, but I needed you." But Stan wasn't sorry. His hit helped win the game.

The Cardinals rode the train down through Illinois to St. Louis. Stan recalled the crowds at several stops.

- At Clinton IL, they chanted "We want Stan, we want Stan."

- Another crowd gathered in Springfield.

- When the train pulled into St. Louis about midnight, more than 1,000 fans greeted it. Musial made a short speech.

Reference: "The Day I Got My 3,000th Hit," by Stan Musial as told to George Vass,

Baseball Digest, 1973 | Top of Page

|

|

|