|

CONTENTS

Greatest Year by a Hitter?

Mahatma, Larry, and the Lip - I

Mahatma, Larry, and the Lip - II

Mahatma, Larry, and the Lip - III

Mahatma, Larry, and the Lip - IV

Mahatma, Larry, and the Lip - V

The Saga of Ray Caldwell - I

The Saga of Ray Caldwell - II

Jake Powell, Racist

The Colossus Prevails

Last Tripleheader

Whose Record Did Babe Break?

Spectator Interference?

Hitting Streak No One Knew About

Baseball

Vignettes Index

Baseball

Page

Golden Rankings Home

|

Baseball

Vignettes - I

Greatest Year by a Hitter?

Stan Musial

Ted Williams

|

In 1948, Stan Musial of the St. Louis Cardinals had arguably the finest year any hitter ever had. Musial led the major leagues in eight categories (second highest also listed to show how far he led in some areas):

- Batting average: .376; Ted Williams (Boston Red Sox) .369

- Hits: 230; Bob Dillinger (St. Louis Browns) 207

- Doubles: 46; Williams 44

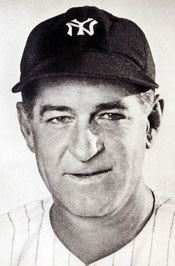

- Triples: 18; Tommy Henrich (New York Yankees) 14

- Slugging percentage: .702; Williams .615

- OPS (On-base Plus Slugging): 1.152; Williams 1.112

- Total Bases: 429; Joe DiMaggio (New York Yankees) 355

- Extra-Base Hits: 103; Henrich 81

In addition, Stan led the National League in four more areas (highest in American League also listed):

- RBI: 131; DiMaggio 155

- Runs: 135; Henrich 138

- Times on Base: 312; Williams 317

- On-base percentage: .450; Williams .497

Adding it all up, Musial led the Senior Circuit in twelve offensive categories in 1948 (although several, such as OPS, were not invented yet). Is it any surprise that he won the NL MVP award? It is also noteworthy that Ted Williams led the Junior Circuit in six categories.

None of this was new for Musial. In 1943, the first year that World War II took a large toll on baseball, Stan led the league in 9 offensive categories. In 1946, the first full season after the War, he again topped the Senior Circuit in 9 offensive categories (plus Games, Plate Appearances, and At-Bats).

|

Mahatma, Larry, and The Lip – I

This is the story of three men whose lives were entertwined in the 1930s and '40s.

- Branch Rickey became GM of the St. Louis Cardinals in 1919. We pick up this story in 1931 when Larry MacPhail bought the Columbus (OH) franchise, including the ball park, for $100,000 under an agreement with Rickey that the club would be part of the St. Louis's pioneering farm system.

- Rickey and MacPhail was not a partnership made in heaven. Branch was a devout Christian, a teetotaler, simple in his lifestyle, highly literate and careful in his speech. Larry drank like a fish, dressed flashily, lived lavishly, and often spoke before thinking. It was inevitable the two would clash, and, even though the Blue Birds enjoyed much success, Rickey fired MacPhail as president of the Columbus team in 1933.

- Larry landed on his feet, however. The Cincinnati Reds ended the 1933 season in last place and deeply in debt. The owner turned the team over to a local bank, which sought someone to run the club and find a new owner. When asked for advice, Rickey recommended MacPhail.

- Larry quickly found a new owner, local car dealer and radio station owner Powel Crosley. MacPhail hired Red Barber to broadcast games and installed the first set of lights at a major league stadium. Most importantly, he laid the foundation for a farm system. After staying the cellar in 1934, the Reds moved up to 6th in '35 and then 5th in '36. However, the 1937 team fell back into the cellar, and Crosley fired MacPhail, in part because of several off field incidents related to Larry's drinking.

Let's back up chronologically and bring in the third protagonist in this drama.

- Leo Durocher played SS for the Yankees in 1928-29 and then the Reds from 1930-32. Although he hit only .238 during those years, he was an excellent fielder with quick hands and rapid release to first. Known for his feistiness, Leo had once challenged Babe Ruth to a fight.

- In 1933, Rickey needed a SS. Charley Gelbert had filled the position admirably on the 1931 World Series champions and the 1932 club. However, a hunting accident after the '32 season had severely damaged his leg, effectively ending his career. So in mid-season of 1933, Branch obtained Durocher and two other players from the Reds for three players, one of whom, Paul Derringer, would became a mainstay of Cincy's pennant winners of 1939 and 1940.

- Durocher played a crucial role for the Gashouse Gang that won the 1934 World Series. However, Leo, like Larry MacPhail, lived a lifestyle at odds with Rickey's austere beliefs. One of his bad habits, which he did not share with Larry, was an addiction to gambling. As a result, he was deeply in debt when St. Louis acquired him. Rickey structured his contract so that the club would set aside part of each paycheck to cover Leo's debts.

- Like Billy Martin in later decades, Durocher did not wear well on a ball club as a player or, later, as a manager. Redbird manager Frankie Frisch had presided over a particularly rowdy bunch, but eventually he tired of Leo. After the 1937 season, Frisch told Rickey: It's him or me. So Branch traded Durocher to the Brooklyn Dodgers for four players.

The second act of this story will be set in Flatbush.

Reference: 1947, When All Hell Broke Loose in Baseball, Red Barber

Top of Page |

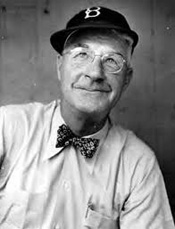

Branch Rickey

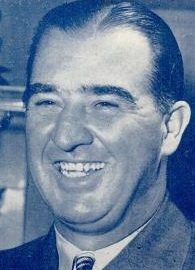

Larry MacPhail

Red Barber

Leo Durocher

|

Larry MacPhail and Babe Ruth

Dolph Camilli

Leo Durocher

Pete Reiser

Pee Wee Reese |

Mahatma, Larry, and The Lip – II

This is Act Two in the drama of three strong-willed personalities whose professional lives were intertwined.

- As had happened four years earlier when Branch Rickey canned him as head of the Columbus baseball team, Larry MacPhail saw a setback turn into an opportunity. The Brooklyn Dodgers were in sad shape, with two sets of heirs of squabbling over who would run the franchise. The majority owner asked Branch Rickey to take over the team. Not interested in leaving St. Louis, Branch recommended his protegé MacPhail. "He hasn't had a drink for a year, just as he promised me."

- When the owner granted his demand for full authority over baseball operations, MacPhail took over the Dodgers for the 1938 season. He immediately set about transforming a team that had finished 6th in 1937 under Burleigh Grimes.

- Larry implemented the same principles he had applied in Cincinnati. He renovated 25-year-old Ebbets Field and inaugurated night games. Handcuffed by a broadcasting ban among the three New York teams through the '38 season, he brought Red Barber from Cincinnati to announce the games for 1939. MacPhail hired Babe Ruth as a coach for the '38 season. Fans arrived early to see Babe take batting practice. Most of all, he transformed the roster, starting with a $45,000 acquisition of 1B Dolph Camilli from the Phillies. Another acquisition was SS Leo Durocher from the Cardinals.

- When the Dodgers sank to 7th in 1938, MacPhail replaced Grimes with Durocher as player-manager. Leo lit a fire under the team, which won 15 more games in '39 to finish third behind the Reds and Cards, the two NL teams both Larry and Leo had previously been associated with. 1940 saw Brooklyn move ahead of St. Louis but still fall 12 games short of Cincinnati.

MacPhail and Durocher finally achieved their dream in 1941.

- With exciting young players like SS Pee Wee Reese and CF Pete Reiser, both 22, and 25-year-old C Mickey Owen, acquired from the Cardinals, the Dodgers won their first pennant in 21 years, edging St. Louis by 2.5 games. MacPhail finally had his pennant, and he had it over Rickey.

- The Yankees won the World Series in five games, with Mickey Owen's miss of the third strike that should have ended Game Four playing a big role.

- 1942 proved to be MacPhail's last year with the Dodgers. Brooklyn blew a 10 1/2 game lead in August as the Cardinals roared to the pennant, then beat the Yankees in five.

- MacPhail left baseball for the army. Meanwhile, St. Louis owner Sam Breadon didn't renew Rickey's contract. So the Dodger owner made the same offer he had tendered five years earlier, and this time Branch accepted.

- Sportswriters asked, "Will Rickey close MacPhail's saloon?" Larry had operated a generous bar in the press room at Ebbets Field. Despite his personal avoidance of liquor, Branch chose not to curtail the practice.

- NL President Ford Frick took the opportunity to enlist Rickey to change several of Leo's bad habits. Frick was tired of Durocher's heated arguments with umpires. He was also concerned about reports of rampant gambling among the Dodgers in clubhouses and on road trips. The new GM lectured his manager publicly about the evils of gambling.

Soon Dodger fans started saying, "Rickey ruint the Dodgers."

- With the war taking its toll on all teams, Brooklyn won 23 fewer games in 1943, then fell to seventh in '44.

- Rickey implemented his philosophy of signing all promising young players even though they would soon be in the service. Branch wanted them in his system when they survived the war. His approach began to pay big dividend after the war ended in 1945.

- The Dodgers moved up to third that season, then lost a playoff with the Cardinals for the '46 pennant.

1947 would bring another pennant, but not with Durocher as the skipper.

To be continued ...

Reference: 1947, When All Hell Broke Loose in Baseball, Red Barber

Top of Page |

Mahatma, Larry, and The Lip – III

Larry MacPhail

Leo Durocher

Branch Rickey

Ford Frick

Happy Chandler

Red Barber

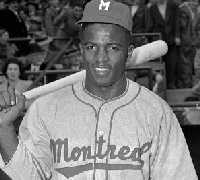

Jackie Robinson

Charlie Dressen

Bucky Harris

|

This is Act Three in the drama of three strong-willed personalities whose professional lives were intertwined. In this act, another strong personality will enter the drama.

- Larry MacPhail left military service in 1945 and became president and part owner of the New York Yankees. That put him back in Big Apple in direct competition for publicity and fan support with the Brooklyn Dodgers, the team that hired him as GM in 1938 and for whom he engineered a pennant in 1941 with Leo Durocher as his manager. Durocher remained in Brooklyn but Branch Rickey, MacPhail's one-time mentor in the Cardinals system, had replaced him as GM.

- MacPhail wasted little time in firing shots across the Dodgers' - or, more specifically, Rickey's - bow. Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis had died in November 1944 after serving as baseball's commissioner for 24 years. The following year, the owners met to choose a successor to fill Landis's giant shoes. Rickey worked hard to get NL President Ford Frick elected baseball's czar. However, MacPhail succeeded in pushing through an outsider, Albert "Happy" Chandler, former Governor of Kentucky. As happened with many of MacPhail's associations, the one with Chandler would also turn sour after several years.

- The Yankee president also targeted the Dodgers' beloved broadcaster, Red Barber, whom Larry had brought to Cincinnati and then to Brooklyn. During the 1945 season, he offered Red $100,000 for three years to broadcast the Yankee games. This forced Rickey to bid $105,000 to keep Barber. Thwarted in his plan, MacPhail hired Mel Allen when he came out of the Army. (In 1973, Barber and Allen would become the first inductees in the Hall of Fame's broadcasting wing.)

By the end of the '45 season, Rickey had formulated his plan to bring a black player to the Dodgers.

- Commissioner Landis had squelched any attempts to integrate baseball. With a new commissioner on the job, Rickey decided it was time to set his plan in motion.

- At an owners' meeting during the '45 season, a secret vote was taken on the issue of signing Negro players. The predictable result was 15-1 against, with Rickey, of course, the lone "aye."

- Nevertheless, a policy committee was appointed to study the matter with MacPhail as chairman. The overwhelming result of the vote and the fact that he was not one of the four members of the committee in no way deterred Rickey from carrying out his plan.

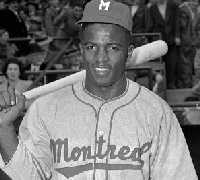

- Late in 1945, Branch signed Jackie Robinson for the Dodgers' farm team in Montreal. MacPhail assailed Rickey because he had "jumped the gun ... baseball had planned to take 'an orderly course' and has established a ... committee. ... Rickey had "raped' the Negro leagues."

- Some, including Red Barber, have wondered whether MacPhail, who brought night baseball to the majors in Cincinnati and radio broadcast of games to several cities, was upset because he wanted to be the one to break the color barrier.

The MacPhail-Rickey feud simmered on the back burner during the 1946 season.

- Robinson created a sensation in the International League, leading the circuit in batting average (.349) and runs scored (113) as he earned the MVP award while leading the Royals to the Little World Series championship.

- Meanwhile, in the Bronx, MacPhail went through three managers. Legendary skipper Joe McCarthy, who had led the Yankees to eight World Series, winning seven of them, in his 15 seasons at the helm, quit May 24, unable to take MacPhail's interference any more.

- Another Yankee hero, Bill Dickey, back with the team after two years in the Navy, took over but lasted only until September 12. Coach Johnny Neun finished the season but announced that he wanted no part of the job.

- In the other major league, the Dodgers returned to contention, losing a best-of-three playoff with the Cardinals when the pennant race ended in a tie for the first time in MLB history.

- Thinking, with good reason, that the addition of Robinson would put the Dodgers over the top in '47, Rickey wanted to re-sign Durocher and his coaching staff. Branch knew that Leo would be a strong advocate for Jackie within the club and against the expected vitriol from opponents. Branch also wanted to keep MacPhail from snatching Durocher for the Yanks.

- As Leo's right-hand man and 3B coach, Dressen asked his manager to intercede for him with Rickey for a raise. On September 16, Charlie orally accepted a two-year deal for $15,000 each season - a hefty sum for a coach in those days. The only proviso Dressen insisted on was that he be released should an opportunity to manage another ML club arise. Rickey was not only amenable but called the Pirates to see if they had filled their opening. (They had.)

- When Rickey asked Durocher about his proffered contract, Leo replied that he was satisfied with it, implying that he fully intended to be back with the Dodgers in '47.

As the off-season stretched into November with no announcement of either Durocher's return to Brooklyn or the Yankees' choice of a manager, rumors persisted that MacPhail had his sight set on The Lip.

- On October 25, the Yankees announced that "Charlie Dressen resigned from the Dodgers yesterday and will join the Yankees" without specifying what position Dressen would hold. Rickey quickly replied, "I not only did not accept his resignation, I am not going to accept." However, since Dressen had never signed his new contract, Rickey had no leverage.

- When Branch wondered whether Dressen would be the new Yankee manager, MacPhail fired back, "Rickey isn't naming Yankee managers yet." But talk increased that Durocher would follow his right-hand man to the Bronx.

- Another Dodger coach, Johnny Corriden, also joined the Yankees.

Finally, on November 6, the Yankees introduced Bucky Harris as their manager.

- At the press conference, MacPhail said: "Durocher contacted me. That is, he sent word to me that he would like to manage the club. I did not tell Leo he could have the job. I did not think he would be the logical man for it."

- However, Durocher told a different story in mid-November. Addressing a luncheon in Los Angeles, he said: "About a month before the season ended, Larry MacPhail called me at my apartment in New York and asked to see me. I went over, and he offered me the Yankee job. I told him I had a verbal agreement with Mr. Rickey and couldn't take it. That was the last I heard of it."

- In his memoir, Nice Guys Finish Last (1975), Durocher wrote: "For reasons of his own, probably nothing more than publicity, [MacPhail] decided it would be nice to get a little feud gong with his old friend and benefactor Branch Rickey ... If it was possible for Larry MacPhail to be embarrassed [about three managers quitting in one year], a highly debatable point, he was in a highly embarrassing position, and he rose to the occasion nicely by making noises all through the winter [actually the fall] that he was negotiating with me. I kept needlng him back by saying, in one way or anoher, that yes, Larry had tried to hire me but I wasn't interested in anything except managing the good old Brooklyn Dodgers. It was a lot of fun and kept us in the papers during the off season. When Larry finally got around to signing Bucky Harris he kept it going by saying that he hadn't been trying to sign me after all, he had only been helping me get a better contract out of Rickey."

- Finally, on November 25, Leo came to Brooklyn for the announcement that he had signed his 1947 contract. "I want to manage the Dodgers till the day I die," Durocher proclaimed.

The Lip would in fact manage no games for the Dodgers in 1947 and only 73 in 1948 before departing.

Next: The Tumultuous 1947 Spring Training

Reference: 1947: When All Hell Broke Loose in Baseball, Red Barber

Top of Page |

Mahatma, Larry, and The Lip – IV

Despite Leo Durocher's fiery personality and his association with gamblers, Branch Rickey wanted The Lip to return as his manager for 1947.

- Rickey liked Leo's courage, baseball savvy, and willingness to do anything to win.

- Most of all, Rickey was confident that Durocher would support Jackie Robinson as he integrated ML baseball. The fact that the rest of the league would oppose Jackie would only make Leo more combative and protective of his rookie.

In a sport permanently scarred by the 1919 "Black Sox" World Series scandal, Durocher was playing with fire by socializing with known gamblers.

- The 1942 Dodgers had a wide-open clubhouse. The players gambled, and Leo gambled with them. Some even thought that the Dodgers played poorly in a crucial September series in St. Louis because they had gambled the night away on the train to the Mound City. At the end of the season, Rickey made it plain to Leo that gambling in the clubhouse and on the ball club must end.

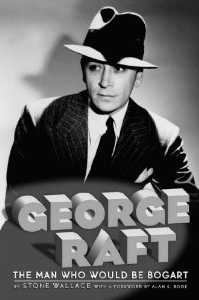

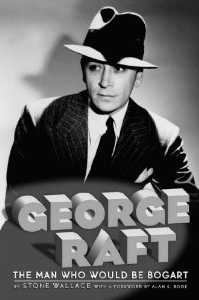

- Another problem for Leo was his association with actor George Raft, a well-known gambler. In 1944, while the Dodgers were in spring training, Raft lived in Durocher's apartment in New York for a week and conducted high-stakes dice games there. Leo usually vacationed at Raft's large house in Los Angeles for several weeks during the off season.

- The influential "muckraking" columnist Westbrook Pegler made an issue of Durocher's shady friends and demanded that Rickey get rid of the "moral delinquent" before Pegler published a series of damning columns. Branch defended his manager, stating that he knew of no occasion when Leo violated the order he had given him after the '42 season.

Then Rickey took a step that he thought would help defuse the situation but which, instead, cost him his manager.

- Branch sent his assistant, Arthur Mann, to Commissioner Chandler's office in Cincinnati to ask Happy to order Leo to move out of Raft's apartment and to stay clear of George and other known gamblers.

- Looking for a chance to look tough on gambling, like his predecessor, Judge Landis, Chandler gave Leo that order on a golf course in California. He also handed Durocher a list of names of known gamblers that he was not to have any contact with. Leo had only a nodding acquaintance with several of them but had socialized many times with two of them, Memphis Engelberg and Connie Immerman. In fact, Memphis had had full reign of the Dodgers clubhouse in 1942.

- Leo was worldly-wise enough to understand the context in which Chandler was acting. A major point-shaving scandal had just hit college basketball, and five minor league baseball players had been banned for life for fixing games. The prevoius December's NFL Championship Game had been marred by charges of a gamblng fix against two New York Giants players.

- So even though Leo insisted he had never been involved in any suspicious activities, he agreed to move out of Raft's house and walk the other way whenever he saw any of the men on the list.

- Subsequently, Chandler defended Leo to the press and asked anyone who had specific evidence of gambling in baseball to come forward. (Pegler's articles failed to provide anything but innuendos.)

Leo's cause suffered from a blow from an unexpected source.

- The priest who directed the Brooklyn Catholic Youth Organization (CYO) announed on March 1, 1947, that he was withdrawing his group from the Dodgers' Knothole Club.

- He cited Durocher as "undermining the moral training of Brookyn's Roman Catholic youth."

- In addition to the gambling allegations, the priest was upset that Leo, raised a Catholic, was about to enter into his third marriage. The bride would be the actress Larraine Day, whose divorce would soon be final.

On the heels of this turmoil swirling around their manager, the Dodgers began spring training in Havana, Cuba. The choice of Havana was an important piece in Rickey's plan to bring Jackie Robinson to Brooklyn for opening day.

- Branch knew that all the southern states, including Florida, where the Dodgers normally trained, had strict segregation laws.

- He also knew that fewer reporters would make the trip to Havana compared to the number usually covering the Florida training camps.

- He also kept Jackie on the Montreal roster and had the Royals train in Havana as well so that they could play exhibition games against the Dodgers. This would lessen the media pressure on Robinson and give his future teammates a chance to see the AAA sensation in action.

One big problem with Havana, though, was that it was a gambling mecca.

To be continued ...

Reference: 1947: When All Hell Broke Loose in Baseball, Red Barber

Top of Page |

|

Westbrook Pegler

Leo Durocher and Laraine Day

Leo Durocher and Jackie Robinson in Havana

|

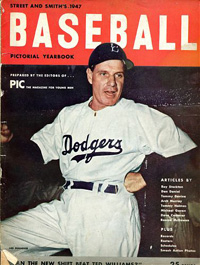

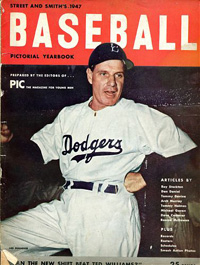

Mahatma, Larry, and The Lip – V

Branch Rickey

Larry MacPhail

Leo Durocher on cover of Street and Smith's 1947 Baseball Pictorial Magazine

Happy Chandler

Burt Shotton

|

The Brooklyn Dodgers traveled to Havana, Cuba, for their 1947 spring training.

- Connie Immermann owned a casino in the city. Memphis Engelberg also visited while the Dodgers were in training.

- Dodgers skipper Leo Durocher avoided them since he was under strict orders from Commissioner Happy Chandler to stay clear of known gamblers. Leo spent his time at the daily practices and games and in his hotel room.

Another key step in the unfolding drama took place when Larry MacPhail's Yankees flew out of Florida for three exhibition games with the Dodgers in Venezuela followed by two more in Havana.

- After the first contest in Havana, Dodger GM Branch Rickey was furious. Engelberg and Immerman had attended the game in box seats right behind the Yankee dugout.

- Branch told two reporters, one for the Associated Press and the other from one of New York's nine newspapers that, if the two gamblers had tried to sit behind the Dodger dugout, he would have evicted them from the premises. He implied that MacPhail was trying to get Durocher in trouble by bringing known gamblers to the ballpark.

- Would MacPhail's "guests" be in those same seats the next day? Yes, they were. Alerted in advance by Rickey's public complaints, a photographer took a picture of them behind the Yankee dugout. Afterwards, Durocher asked, "Are there two sets of rules, one applying to managers and one applying to club owners? Where does MacPhail come off, flaunting his company with known gamblers right in the players' faces? If I ever said 'Hello' to one of those guys, I'd be called before Commissioner Chandler and probably barred."

- MacPhail replied indignantly. "In the first place, it is none of Durocher's business who I have in my box. ... I understand that in the box next to me were two gentlemen later identified as alleged gamblers. I had nothing to do with their being there."

After the Yankees returned to Florida, MacPhail upped the ante in the dispute.

- He charged that the statements by Rickey and Durocher charging MacPhail with sitting with known gamblers in Havana constituted "conduct detrimental to baseball."

- MacPhail called on Chandler to "call a hearing to determine responsibility for the statements and then whether they are true or not."

- It's not clear what MacPhail wanted from the hearing - perhaps a simple apology from Rickey and Durocher. Larry counted on the fact that Chandler owed him a favor because the Yankees president had garnered votes for Happy's election over Rickey's nominee, NL President Ford Frick.

With a chance to show that he was a strong leader in the style of Judge Landis, Chandler granted the hearing, which took a turn that no one expected.

- The hearing, which some regarded as a trial, began March 24 in Sarasota FL. The press was barred. Rickey was absent at a funeral.

- When Durocher took the witness stand, he apologized for his printed statements. MacPhail got up and shook Leo's hand. "That's good enough for me," Larry said and sat down.

- Chandler then unexpectedly switched the questioning to the old charges of gambling in the Dodgers clubhouse, which had nothing to do with MacPhail's complaints. Leo admitted he gambled with P Kirby Higbe but explained that he gave back any money he won from him as a "bonus" when Kirby pitched a good game.

- Leaving the issues unsettled, Chandler asked MacPhail if there was anything else to be covered. Larry replied that he was not satisfied with the hearing, that he wanted a statement of admission, denial, or apology from Rickey.

Chandler set the follow-up hearing four days later in St. Petersburg.

- This time, Rickey was present, having read the detailed report of the first hearing written by his assistant, Arthur Mann.

- Rickey repeated his remarks about undesirable individuals sitting in the Yankees club box.

- After further inconclusive testimony, Chandler cleared the room except for Rickey, Walter O'Malley, acting as lawyer for the Dodgers, and Mann.

- Happy walked over and asked the three (according to Mann), "How much would it hurt you folks to have your fellow out of baseball?" Caught off-guard, Rickey replied, "Happy, what on earth is the matter with you?"

- Chandler produced a letter that he said came from a "big man" in Washington who demanded that Durocher be banned from baseball. The commissioner then closed the hearing without making any pronouncement.

An event in pro football may have influenced what Chandler did next.

- On March 3, NFL Commissioner Bert Bell indefinitely suspended two New York Giants players, Merle Hapes and Frank Filchock, for waiting a week to report bribe attempts before the championship game the previous December.

- Writers immediately labeled the incident the biggest scandal in sports since the 1919 Black Sox.

No one will ever know whether Chandler had already decided what he would do or took action after noting the positive feedback Bell received for his decision. At any rate, on April 9, Chandler called Rickey and announced the decisions he had made before releasing them to the press in Cincinnati.

- The Brooklyn club was fined $2,000, as were the Yankees.

- Leo Durocher was suspended from baseball for a year.

- No one was more shocked by Chandler's actions than MacPhail, who admired Leo and simply wanted an apology from him.

Less than a week before the season started, Rickey had to hire a manager who would have to deal with the addition of Jackie Robinson to the roster. Branch turned to his old friend Burt Shotton, who guided the Dodgers to the '47 NL Pennant.

Reference: 1947, When All Hell Booke Loose in Baseball, Red Barber

Top of Page |

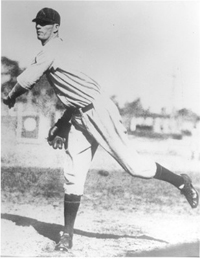

The Saga of Ray Caldwell – I

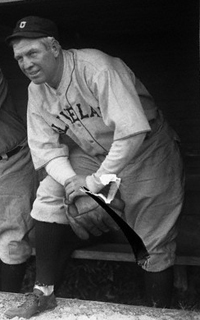

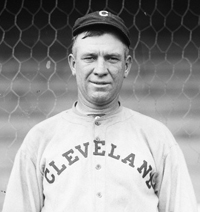

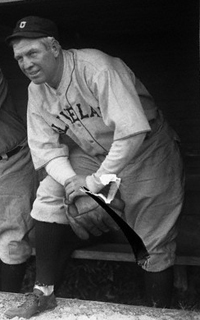

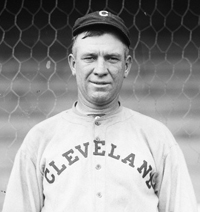

On August 19, 1919, with his Cleveland Indians in third place seven games behind the Chicago White Sox, player-manager Tris Speaker tried to improve his pitching for the stretch run by acquiring Ray Caldwell, whom the Red Sox had recently released. The move surprised many observers.

- Caldwell had compiled a 7-4 record and 3.96 ERA with the Red Sox in his tenth season in the American League. Yet Boston had let him go because of his unreliability.

- To put it bluntly, Ray had a severe drinking problem that drove every one of his managers crazy.

- When he "kept in condition" (to use a euphemism popular among sportswriters at the time), the 6'2" 190 lb righty could compete with the best in the league. In fact, Washington owner Clark Griffith offered to trade his ace, Walter Johnson, for Ray in 1914 when both pitchers were being wooed by the new Federal League.

- Ray's statistics reflected the up-and-down nature of career as he, by turns, controlled his alcoholism, then surrendered to it for long stretches.

- 1911: In his first full season in the majors, Caldwell finished 14-14 with 3.35 ERA for the 6th place New York Highlanders

- 1914: After two years plagued by arm injuries, Ray went 18-9 with 1.94 ERA for the Yankees (as they had been renamed the previous season)

- While enjoying what would turn out to be the best year of his career in '14, Ray couldn't stand prosperity. In August, after a couple of losses, he "went by the wayside" and disappeared on a western roadtrip. Manager Frank Chance had warned Ray that he would not tolerate a renewal of his drinking. Altogether, Chance fined his miscreant $900. Still, the Federal League came after Caldwell with a $2,500 advance in September. In hopes of keeping Ray from jumping leagues, Yankee president Frank Farrell agreed to rescind the fines. This was the last straw that caused Chance to resign.

- 1915: Ray won 19 games while losing 16 with a 2.89 ERA as the Yanks rose to fifth place in the eight-team league. He was often plagued by lack of support. In one stretch of five games in August, the Yankees scored only one run for him, which enabled him to win 1-0 over Detroit. A solid hitter (.248 lifetime average), Ray tripled and scored the only run of the contest.

- 1916: A shattered kneecap hampered Caldwell, who fell to 5-12 but with a 2.99 ERA. With the team dropping in the standings, Ray disappeared in mid-August, incurring a $100 fine and 15-day suspension from manager "Wild Bill" Donovan. Reports surfaced that Ray underwent treatment for alcoholism at a St. Louis hospital.

Caldwell came to spring training determined to make 1917 his best season.

- Rumors had circulated over the winter that a pitcher named Collins for the Colon team in Panama bore a striking resemblance to Ray Caldwell.

- The Yankees gave him another chance, mostly because they needed him to compete for the pennant.

- He continued to lose low-scoring games. Yet on June 23, he beat Philadelphia in both ends of a doubleheader. Donovan pulled him after six innings of the opener with a 9-0 lead. Then Ray won the nightcap 2-1.

Athletics manager Connie Mack said: "Put Ray Caldwell on a winning team, and he would be one of the greatest pitchers of all time."

- But just a few days later, the old bugaboo resurfaced. After carousing all night and failing to report the next day, Caldwell was fined $100 and suspended for ten days. When he returned to action, he threw 9 2/3 innings of shutout ball in relief for a win over the Browns in St. Louis. Then that night he was arrested by police and charged with stealing a $150 ring. A few weeks later, Ray's wife sued him for support for herself and their seven-year-old son, claiming he had abandoned them.

- His final tally for '17 was 13-16/2.86, not bad considering his multiple suspensions.

Miller Huggins took over the Yankees for 1918. His approach to the Caldwell Problem was to assign two private detectives to keep him out of trouble, a ploy that was only partially successful.

- Ray injured his knee in spring training and developed a lame arm.

- By May, he regained his form and pitched well. On May 13, Huggins used him as a PH, and Ray responded with a bases-clearing double to beat Detroit 3-2.

- His July 1 victory over Philadelphia put the Yankees in first place. But, as usual, the euphoria was followed by a summer swoon to an eventual sixth-place finish.

- In mid-August, Ray left the club without notice to work for a drydock company in New Jersey. He and several teammates did so in order to avoid the military draft as their company provided an "essential service" to the nation's World War I effort.

The Yankees had finally had their fill of Mr. Caldwell.

- They traded him to the Red Sox in December in the first of many trades between the two clubs, the most famous of which brought Babe Ruth to New York.

- Like all his predecessors, Ray's manager in Boston, Ed Barrow, vowed to curb Ray's antics but didn't help his prospects when he assigned Babe Ruth to room with Caldwell on the road.

- The Red Sox released Ray in early July.

A few weeks later, Speaker decided to take a chance on the talented but troubled hurler. Tris had a novel approach he wanted to try.

Reference: The Baseball Biography Project: Ray Caldwell, Steve Steinberg, Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) |

Ray Caldwell

Frank Chance

"Wild Bill" Donovan

Miller Huggins

Tris Speaker

|

The Saga of Ray Caldwell - II

Ray Caldwell

Tris Speaker

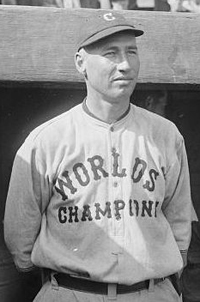

Jim Bagby

Stan Coveleski

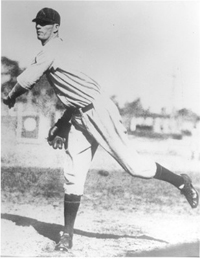

Lefty Grove

|

Manager Tris Speaker prepared a unique contract for P Ray "Slim" Caldwell when the latter joined the Indians in August 1919.

- Clauses specifically aimed at Ray's problems were inserted into the standard contract.

After each game he pitches, Ray Caldwell must get drunk. He is not to report to the clubhouse the next day. The second day he is to report to Manager Speaker and run around the ball park as many times as Manager Speaker stipulates. The third day he is to pitch batting practice, and the fourth day he is to pitch in a championship game.

- According to Franklin Lewis in The Cleveland Indians:

Slim looked up. "You left out one word, Tris," he said. "Where it stays I've got to get drunk after every game, the word not has been left out. It should read that I'm not to get drunk."

Speaker smiled. "No, it says that you are to get drunk." Slim shrugged his shoulders. "Okay, I'll sign," he conceded.

- The reverse psychology worked. Ray started six games the rest of the season and won five of them. He compiled a sparkling 1.71 ERA.

A fantastic event occurred in one of the games Caldwell pitched.

- On August 24, Ray took the mound for the first time in Cleveland's League Park. He led the Philadelphia Athletics 2-1 with two outs in the top of the ninth.

- According to the account of the game in the Sandusky (OH) Star-Journal, "A bolt of lightning struck near the park in the ninth and Caldwell was hurled to the ground as a result. He recovered and retired the side, having to pitch to only one batter."

- A wire service report in The San Antonio Evening News added more details.

Ray Caldwell, pitching for Cleveland against the Athletics here yesterday, was knocked down and the entire field shocked by a flash of lightning which seemed to shoot directly into the pitcher's box. Caldwell was dazed for several moments, but pitched the remaining inning. The flash came during a rain and was accompanied by a deafening crash of thunder. One of the players touched Caldwell on the head and leaped into the air. He said the pitcher seemed to be crackling with electricity.

- As a side note, former sportswriter Robert Ripley, who started the syndicated newspaper feature "Ripley's Believe It or Not," paid Caldwell $100 some years later to appear on his radio show to tell the lightning story.

- On September 10, Ray tossed a 3-0 no-hitter against his longtime team, the Yankees. Two days later, the Indians began a 10-game winning streak that pulled them within four games of the White Sox. Cleveland lost 3 of their last 4 to finish second, 3.5 games out.

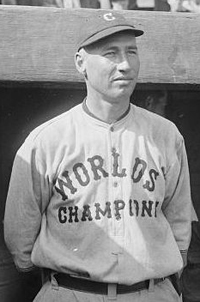

The Indians' fine play the last months of the 1919 season carried over to 1920 and propelled them to the World Series championship.

- Finally pitching for a top-notch team, Ray won 20 games in 1920 with a 3.86 ERA as Speaker's #3 starter behind Jim Bagby and Stan Coveleski. Part of the reason for the ERA being higher than Ray's numbers earlier in his career is the introduction of the livelier ball that year.

- Ray had added a spitball during his brief stint with Cleveland in 1919 – probably taught to him by Coveleski – and, for that reason, he was one of the 17 pitchers permitted to throw the pitch for the rest of their careers when the owners banned the spitball before the 1920 season.

- Not even once did Speaker need to discipline Caldwell for violating training rules.

- Ray had a disappointing World Series. He started Game 3 but was pulled after giving up two runs in only 1/3 of an inning.

Ray's honeymoon with Speaker finally ended in 1921.

- Tris moved him to the bullpen. After 33 starts in 1920, Caldwell began only 12 contests in '21.

- In early September, Speaker suspended Ray for violating "rules of discipline." When he begged for another chance, Tris reinstated him.

- Ray then garnered two of his six victories for the season, one of which was his only shutout. His 5-1 victory over Boston put Cleveland in a tie for first with the Yankees. The Indians then went to New York for a crucial four-game series with the Yankees.

- After the teams split the first two, Caldwell started the crucial third game and was blasted from the mound in the second inning of a 21-7 rout. [Open question: Did Ray go on a bender before that pressure-packed start?] The Yankees won the final game to take a two-game lead with only four to play.

- Cleveland lost 3 of 4 to the White Sox to close out in second place by 3.5 games.

Ray never started another major league game.

- He spent 12 more years in the minors.

- In 1923, he pitched for Kansas City, the American Association champions, in the Little World Series against the Baltimore Orioles of the International League.

- Baltimore's southpaw phenom Lefty Grove beat Ray in Game 2, 3-1, but Ray won their duel in Game 6. KC won the series in the full nine games.

- Despite putting up some good numbers in the minors, Caldwell never got another ML offer.

|

Reference: The Baseball Biography Project: Ray Caldwell, Steve Steinberg, Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) |

|

Memorial Day, 1938. The biggest crowd ever to see a baseball game to that point – 83,533 – gathered at Yankee Stadium for a doubleheader with the Boston Red Sox. The two-time defending World Series champion Yankees swept the twinbill, 10-0 and 5-4.

The afternoon's highlight (or lowlight) was a fracas during the first game that included fisticuffs.

- Irritated by a bad pitch which hit him on the leg, Yankee LF Jake Powell, walked out to challenge the Red Sox pitcher. Before any blows were struck, Player-Manager Joe Cronin tried to intervene.

- Cronin, years later: "Archie McKain, a little lefty, was pitching for us. ... Powell came out toward McKain and made some threatening gestures. I thought he was overreacting, so I came in from SS."

- The confrontation developed into one

of the bitterest melees ever staged in Yankee Stadium. Cronin and Powell exchanged blows

before a bigger crowd than would

see Barney Ross and Henry Armstrong fight the next night, and Max Schmeling and Joe Louis battle on June 22.

- Cronin: "There were some words, and we started punching and rolling around, and Cal Hubbard, the umpire, threw us both out."

But the tussle didn't stop there.

- Cronin: "In those days, the visiting team had to go through the Yankee dugout to get to its locker room. As I went down the runway, Powell began popping off some more. It was dark, a lot of beer barrels around, but we squared off again. The trouble was, this was enemy territory. I was surrounded by Yankees. They started to gang up on me, but then Hubbard showed up. He was a big guy, a former All-American football player and a pro, and he must have thought the odds were against the Irish kid. He tossed me one way and Powell the other, and that was the end of the fight."

- Neither Cronin nor Powell played in the nightcap.

Two months later, Powell was suspended by the commissioner for a remark he made during a radio interview.

- On July 29, 1938, Powell, who was born in Silver Spring MD, did an interview with WGN Radio announcer Bob Elson before a game with the White Sox at Comiskey Park.

- Elson asked what Powell did during the off-season. Powell replied that he was a policeman in Dayton OH.

- When Elson inquired as to how he stayed in shape, Jake replied that he cracked blacks over the head with his nightstick. Only he didn't say "blacks" but used a common racial slur instead.

- Hundreds of angry listeners called WGN to complain. Others complained to the Chicago office of baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Before the next day's game, a delegation of black leaders presented a petition to the umpires demanding that Powell be banned from baseball for life.

- Forced to act in the face of such public outrage, the commissioner suspended Powell for ten days. The Sporting News reported that this was the first time a ML player had been suspended for a racist remark.

Those were the facts as the public knew them. But the story had other twists.

- The Washington Nationals had traded Powell to the Yankees in 1936 for blatant racist Ben Chapman from Nashville TN. Chapman later became the manager of the Philadelphia Phillies. In that role, he did his best to make Jackie Robinson's life miserable in his rookie season of 1947.

- The Nationals shipped Powell to the Yankees because he was unpopular with his teammates despite his .312 average and 98 RBI in 1935. He had deliberately collided with Detroit's Jewish 1B Hank Greenberg, breaking Hank's wrist and ending his 1936 season after 12 games. Furthermore, Powell's gambling had driven him deeply into debt, and his creditors threatened to sue the Nationals to settle the score.

- Powell lived in Dayton during the off-season but never worked for the city's police department. Friends told the The Dayton Daily News that his remark about blacks was his idea of a joke.

Black writers kept up the pressure on the baseball establishment following Powell's suspension.

- They urged their readers to boycott Yankee games and the sponsors of the radio broadcasts.

- This action forced the Yankees to apologize and ask what they could do to improve relations with the black community.

- Black leaders also demanded that the Yankees trade or release Powell. When Powell took the field in a game at Washington's Griffifth Stadium, spectators threw bottles at him.

The incident in Chicago derailed Powell's promising baseball career.

- Powell stayed with the Yanks two more seasons but played sparingly. He was released in 1941.

- He returned to the Nationals in 1943 during the player shortage caused by World War II. Washington traded him in 1945 to Chapman's Phillies. He played no more ML games after that season.

- In 1948, Powell was arrested in Washington for passing bad checks. While being questioned in a police station, he shot himself to death. He was only 40 years old.

|

Jake Powell

Joe Cronin

Cal Hubbard

Jackie Robinson and Ben Chapman in a picture that Commissioner Happy Chandler mandated in 1947.

|

References: "Why the Red Sox Hate the Yankees," Ray Fitzgerald, The Best of Baseball Digest

"Public Slur in 1938 Laid Bare a Game's Racism," Chris Lamb, The New York TImes

|

|

The

Colossus Prevails

While

playing for the Red Sox

in 1918, Babe

Ruth played one of the greatest, if not the greatest, stretch

of play in baseball history. From July to early September, "The Colossus"

(as he was known in Boston):

- Pitched

every fourth day;

- Played

either left field, center field, or first base on the other days (he

was quite skillful at first base, his favorite position);

- Allowed

more than two runs in only one of ten starts;

- In

one 10-game stretch at Fenway Park, hit .469 (15-for-32) and slugged

.969 with four singles, six doubles, and five triples.

Ruth

led the Red Sox to the pennant

in a season cut short by the owners on September 2 because of public pressure

for players to fight in World War I. Boston

defeated the Chicago Cubs

in six games in the World Series. Because Chicago

started all lefties, Sox

manager Ed

Barrow (later the long-time Yankees

General Manager) used Babe only as a pitcher. He shutout

the Cubs in game 1 and extended

his scoreless innings streak to 29 2/3 innings in game four before the

Cubs pushed across a run.

Ruth's Series pitching record was not broken until 1961

by Whitey

Ford. Of course, 1918 was the last Red

Sox World Series championship until 2004.

Reference:

Deadball Stars of the American League, The Society for American

Baseball Research, 2006 |

|

Last

Tripleheader

The

Cincinnati Reds and Pittsburgh

Pirates played the last major league tripleheader at Forbes

Field in Pittsburgh on Saturday, October 1, 1920. (Sunday sporting

events were banned in Pennsylvania which explains why the teams couldn't

play one or two games on Sunday, October 2.) Pirates

rookie third baseman Clyde Barnhardt set a record by

hitting safely in three games in one day, a mark that will probably never

be broken since tripleheaders are not played any more.

-

Game 1: Barnhardt doubled and singled

off Reds starter Ray

Fisher. The Pirates

lost 13-4 in just over two hours.

-

Game 2: Clyde doubled in four trips

in another loss, 7-3. This game took 1 hour and 56 minutes.

-

Game 3: This was a makeup of a rained out game originally

scheduled for Cincinnati earlier in the week since Pittsburgh

batted first. Barnhardt went 1-3 in a game called after

six innings because of darkness. The Pirates

salvaged this game 6-0.

After

the tripleheader, the Pirates

traveled to Chicago for a makeup game against the

Cubs to end the season. The Pirates

won the Sunday finale 4-3 to finish 79-75 in fourth place. (It's not clear

87 years later why this game was played. Pittsburgh

was three games ahead of Chicago

and had clinched fourth place. In 1920, only players on the second and

third place teams in each league shared in the World Series money. Perhaps

the game had been rescheduled when it was uncertain whether it would make

a difference. Or maybe the Cubs

just wanted the revenue from a final Sunday game. The 1920 schedule

shows that the Pirates often

began road series on Sundays after playing at home on Saturday.)

|

Whose

Record Did Babe Break?

On July

18, 1921 in Detroit, Babe Ruth hit the 139th home run

of his career. The four-bagger was estimated to have traveled 500 feet.

Unknown to anyone at the time, Babe thereby broke the

major league record for most career home runs held by Roger

Connor. Writers thought that Babe had set

the record with #118 to surpass the total of Gavvy

Cravath.

The 6'3"

200 pound Connor began his big league career in 1880

with Troy City in upstate New York. He came to New York

to play in 1883. He, Buck

Ewing, and John

Montgomery Ward were so good that manager Jim Mutrie

called them "my giants!" So this is how Barry Bonds'

current team got its nickname. In 1886 Connor clouted

a ball over the billboards – the first and only time anyone hit

a ball out of the old

Polo Grounds. Some Giants

fans gave Connor a $500 gold watch to commemorate the

event – quite a present for 1886! He finished his major league career

in 1896. Roger died in 1931.

Only when

Hank Aaron broke Ruth's career record

in 1974 did researchers discover the facts about Connor's

record. This led to his election to the Hall of Fame in 1976.

Reference:

"Going Deep, Before Bonds And Aaron And Ruth," George Vecsey,

New York Times, May 13, 2007 |

Spectator

Interference?

Ever heard

of verbal spectator interference? It was called when the Cardinals

played the Cubs at Wrigley

Field on Sunday, April 19, 1931. With Ernie Orsatti

on second, St. Louis' Jim

Bottomley of the drove a ball to the edge of the overflow

crowd in left. As left fielder Riggs Stephenson tried

to make the catch, a fan shouted loudly near Stephenson

who muffed the ball, which bounced into the crowd. Umpire Charley

Moran ruled that the fan "interfered" with Stephenson

making the play. Moran called Bottomley

out but awarded Orsatti third base since he would have

made third had Stephenson caught the ball. The Cardinals

protested the Cubs 4-1 victory,

particularly since the game was played on the Cubs

own field. So presumably the "interfering" fan was

for the home team. However, National League president John Heydler

denied the protest. The loss was the Cards'

first after five straight wins to start the season, which would end with

a World

Series victory over the Philadelphia

Athletics.

Reference: Baseball Digest, June

2007

|

Hitting Streak No One Knew About

As Joe DiMaggio's 1941 hitting streak grew game by game, researchers hit the record books to ascertain the targets he was aiming for.

- People recalled George Sisler's 1922 string of 41 straight games with at least one hit. Research soon unearthed a 44-game streak by Willie Keeler in 1897.

- The discovery of Sisler's and Keeler's feats added pressure to DiMaggio who, of course, surpassed Wee Willie's record by 12 games.

It is now known that Keeler's 44-game streak was not the longest in major league history at that time. Research subsequently uncovered a 52-game skein from the year 1887, which would seem to be the second longest in history after Joltin' Joe's. Or should it be so honored?

- Dennis Patrick Aloysius Lyons, 3B of the Philadelphia Athletics of the American Association (AA), was credited with at least one hit in every game from June 24 through August 27.

- I used the phrase "was credited with at least one hit" advisedly. You see, the controversy comes about from a rules change prior to the 1887 season that scored a base on balls as a one-base hit.

- In an attempt to add more offense to baseball, the Joint Committee on Rules formed by the AA and its rival National League, legislated a number of changes, none of which caused controversy at the time.

- In addition to counting a walk as a hit, the Committee also lowered the number of balls needed for a free pass from six to five.

- The strike count was increased from three to four.

- A batter hit by a pitch could take first base.

- Flat-sided bats were allowed.

- The practice of the batter calling for a high or low strike zone was eliminated, replaced by a standard zone from the batter's shoulder to his knee.

As you have probably guessed, the new rule counting a walk as a hit helped Lyons prolong his streak.

- Lyons, a 5'7" right-handed batter, started his rookie season with the A's hitting well. In one stretch in April, he collected 16 hits in 20 at bats. In May, he launched a 19-game string during which he batted .453 and hit three HRs, which would prove to be half his season's total.

- He started his historic run on June 24 with a single off "formidable lefty" Matt Kilroy. For the next 21 games, he got at least one hit "the old fashioned way." In fact, in most games, he got two safeties.

- The first controversy surrounds game #22 of the streak. After six innings, Lyons had managed only a base-on-balls hit off Cleveland's Mike Morrison. The game ended in that inning when the Blues protested a balk call so long that the umpire forfeited the game to Philadelphia. Under the rules of that era, the batting results counted.

- Lyons maintained the streak with ease for 21 more games. In one stretch, he banged out 20 hits in 27 at bats.

- In game #44 on August 19, he got two walk-hits in six appearances against Joe Murphy of the home-standing St. Louis Browns. (Murphy was "a marginal player who also served as the baseball editor for a local newspaper.")

- Over the next eight contests, Denny went 17-for-38.

- The A's then traveled to Cincinnati, Lyons' hometown, to face the Redlegs. On August 27, Tony Mullane held Denny hitless in five at bats to end his streak at 52.

- After a season in which batting averages were considerably inflated, the Rules Committee rescinded the base-on-balls hit rule. However, the 1887 statistics were published in the Reach and Spaulding Official Baseball Guides.

Of course, no one realized Lyons had a streak going at the time. Consecutive games with a base hit was not a statistic that anyone paid attention to until DiMaggio's run. But after Lyons' achievement was unearthed about 75 years after the fact, a revisionist committee spoiled Denny's party.

- In 1968, MLB formed the Special Records Committee to resolve statistical issues raised by differing rules in some years in baseball history.

- The committee decided that the 1887 hitting statistics must be revised to conform to the rule in effect before and after 1887. Not only was Lyons' streak expunged from the record books but also the .492 batting average of Tip O'Neill, which would be the all-time record for one season, was recalculated as .435. Lyons' third-place average of .469 average was reduced to .367.

- The 1968 rulings of the Special Records Committee did not sit well with many historians, who believe that statistics should not be recalculated to fit modern standards. In 2000, MLB reversed course and ruled that records from any given season should be honored in accordance with the rules then in effect.

- Still, many lists of consecutive game hitting streaks do not grant Lyons his second-place standing behind DiMag. On the other hand, Denny is included in Consecutive Games on Base streaks, which Ted Williams (1949) heads with 84, ten more than DiMaggio's 1941 on-base string. (Joe reached via a walk the day before the started his 56-game tear and also walked in the game that ended the streak before embarking on a 16-game hitting streak. Finally, on August 3, Joe did not reach base.)

|

Joe DiMaggio

George Sisler

Willie Keeler

Denny Lyons

|

Reference: "Denny Lyons' 52-Game Hitting Streak," David Q. Voigt, The National Pastime, 1993

Top of Page

|

|

|