Baseball Short Stories - 14

"Get Him the Hell Off My Ball Team"

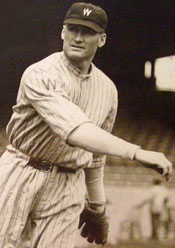

Rube Waddell became a Hall of Fame pitcher for Connie Mack's Philadelphia Athletics in the new American League. But before he joined the A's, he played for Louisville, Pittsburgh, and Chicago in the National League. Waddell was undoubtedly the biggest "flake" in the history of baseball.

Here's an excerpt from Alan H. Levy's book Rube Waddell: The Zany, Brilliant Life of a Strikeout Artist. As the 1901 season approached and the players reported for spring training, Ban Johnson and the American League took off the gloves. Johnson had prepared well, and he was ready to go into direct competition with the senior circuit. ... Johnson set up teams in two of the cities the NL had abandoned — Baltimore and Washington. And he placed three more teams in direct competition with the National League, setting up shop in St. Louis, Boston, and Philadelphia. Connie Mack moved from Milwaukee to Philadelphia to manage the new Athletics.

The baseball wars heated up even more when the owners of these new teams began raiding National League rosters, offering fat salary increases to lure players away.

The name Waddell certainly occured to some of the American Leaguers. Rube was not yet 25, but was already quite the item. No pitcher in baseball had ever become such a benchmark so quickly as did the Rube. The Pittsburgh papers postulated that, despite his fame, or rather because of it, Rube would be secure. "Everyone knows Waddell is a good pitcher, but everyone in baseball is also aware that he is hard to handle."

L-R: Ban Johnson, Connie Mack, Rube Waddell, Barney Dreyfuss The American League owners had agreed with one another as to who could court which player. Rube was "given" to Boston. The Pilgrims knew all about Waddell. Nonetheless, they were "hard after Rube" according to Barney Dreyfus (the owner of the Pirates). The Pilgrims offered Rube nearly double his salary. Rube was firm, though: "I'll pitch for Pittsburgh or for no one. I don't like that town of Boston anyhow. I'll stick to Pittsburgh."

Connie Mack went quietly behind the backs of his Boston brethren and wrote Rube that if he went to Boston and did not like it, he could pitch for Philadelphia and earn $2000 more than either his Boston or his Pittsburgh figure.

Mack later reflected that Rube was never concerned with money; he had the mind of a child. A child will always focus on the positives, and Rube was doing just that amidst all the baseball raiding that spring. Things were good in Pittsburgh, and Pittsburgh was where he was going to stay. He was not going to think about any previous problems, let alone matters like labor unions or salary offers from competitors, and he likely believed, albeit naively, that others like Dreyfuss and Fred Clarke (manager of the Pirates) felt the same way. To Rube this wasn't business, it was baseball.

Having nearly won the pennant in 1900, Clarke and the Pirates were quite optimistic about the new season. They all went off to Hot Springs AK for pre-season training. Rube was the life of the party on the train, singing songs all the way down. Connie Mack once pleaded with Rube to give up his life of "wine, women, and song." Rube responded by asking if it was all right if he just gave up singing. On that long train ride down to Arkansas, many a Pittsburgh Pirate wished he had, as the Rube could always be depended on to sing very badly and very loudly.

Clarke put the team through daily regimens of running, calisthenics, and baseball. The first day out, the team ran a three-mile loop. Rube got lost. He made the most of it, though. He had brought a gun with him, so he got in some hunting and arrived back proudly displaying several ducks. Clarke shook his head. There was a method to Rube's madness here, however. The previous day it had been raining, and everyone stayed inside except Rube. He went out looking for the ball field. During his search he got lost then, too, so bringing the gun along for the next day's run seemed a good idea. Rube logic!

Rube was the toast of the town, naturally. Out of the blue, folks sent him baskets of Easter eggs. When he went to Hot Springs' new movie house, the band struck up "When Reuben Comes to Town." Rube immediately took the podium and conducted. Thankfully, he did not break into song.

L-R: Fred Clarke, Honus Wagner, Rube Waddell with Athletics Clarke and the Pirates were a rough and tumble lot. Modern managers would have heart attacks at some of the "training" Clarke employed, given how it imperiled his star players. On April 5, for example, Clarke oversaw an intra-squad game — of football — with no pads, no helmets, just a ball and a bunch of very large men. And this was no mere game of "two-hand touch." Honus Wagner took a mean elbow in the face and spent much of the afternoon repairing his bleeding countenance in a cold stream.

Rube took the game seriously ... Midway in the game Rube was going after a loose ball and, in rugby-style rules of the day, attempted to kick it. But just as he gave a mighty swing with his leg, an opponent grabbed the ball. Rube thus did a "Charlie Brown," kicking nothing but air. His momentum swung him completely around. He landed on his head and "made a large noise like an Indian." The rest of the team thought he was faking, and the game went merrily on. The doctor said Honus Wagner had a fractured nose and Waddell a sprained ligament in his right hip. Both turned out for practice the next day anyway. Rube was a little stiff and sore, so two days after the football game, he was excused from practice. He went out to the gate, sold tickets, and greeted fans. Baseball, springtime, and the Rube; it was an irrepressible combination.

The Pirates left Arkansas and journeyed to Cincinnati for the season opener. Unfortunately it rained. Clarke was never willing to sit still, if only for the mischief Rube would doubtlessly create. He secured the use of the practice facilities of a nearby army base. The servicemen all turned out, mainly to see the Rube. A number of them were recent veterans of the war with Spain, and Rube ended up receiving a host of souvenirs from Cuba and the Philippines.

The Pirates finally opened their season against Cincinnati on April 22. They won.

Rube's first start came the next day against St. Louis. He was great for six innings. In the seventh, however, "the balloon could easily be seen going skyward." The Cardinals scored five runs, two of which came via a wild throw from Rube as he was fielding a bunt. Rube could be troubled when dealing with pressures, and he was feeling them since one of the new National League rules demanded rosters be trimmed to 16 players by May 1. The Pirates were over the limit. Rube pitched in a practice game the next day against a local college. The following day the Pirates sounded an old refrain: where is Rube?

Rube had gone home to Prospect PA, with a few refreshment stops on the way. His father brought him back to Exposition Park on May 2. John Waddell, Sr., had once met with Pirate management and asked them to be patient with his son, feeling screwiness ran in the family and admitting to being a bit off himself. Barney Dreyfuss had smiled at it all, but no one could mollify Clarke with such a tidbit of insight.

Clarke immediately tossed Rube out to the mound to face the Chicago Orphans, as they were then called (sometimes they were called the Remnants. "Cubs" came in 1905.) With his father in the stands, Rube showed nothing — no speed, no snap on his curves, no control. In the first inning he gave up three hits, a wild pitch, and four walks. Rarely before had Rube walked four in a game. On this afternoon, Chicago had batted all nine players before Clarke relieved Rube with just one out in the first.

The day after the loss to Chicago, Rube received a letter from a local furniture dealer: "If you lose your position with the Pittsburgh club owing to the game you pitched against Chicago on Wednesday, we will give you $50 a week to drive one of our delivery wagons." Rube was certainly big enough to handle the task of furniture moving, and, annualized, the weekly salary topped the paltry $1200 Dreyfuss was paying him.

Maybe Rube should have taken the offer from the furniture company, for that night Clarke stormed into Dreyfuss' office. "Sell him, release him, drop him off the Monongahela Bridge," Clarke fumed. "Do anything you like, as long as you get him the hell off my ball team!" When Rube heard he had been sold, he ran into Dreyfuss' office and demanded half of the selling price. "You can't have it all," Rube argued. (Rube logic!) Dreyfuss went him one better. "You can have it all," Dreyfuss calmly replied. "It's right here on my desk." And there it all was — a cigar. Rube had been sold for a stogie. On May 3, the Chicago team left Pittsburgh, and Rube was on the train with them. He was now an Orphan.

Editor's note: The story of Waddell being sold for a cigar has been debunked. While the sale price was never disclosed, Chicago had shown a great deal of interest in Rube, and Dreyfuss wasn't about to give away so valuable a commodity. It seems plausible that Barney told Rube he was sold for a cigar to end Waddell's demand for half the purchase price.

The Benedict Arnold of Baseball

Baseball America: The Heroes of the Game and the Times of Their Glory, Donald Honig (1985)

Gambling was so widespread in the country that many of its higher-rolling practitioners were looked upon as respectable men. Indeed, before baseball became more discriminating about who it let through its executive turnstiles, ball clubs were occasionally controlled by men euphemistically known as sportsmen. Frank Farrell, one of two partners who were the first owners of the New York Yankees franchise, was one of the city's best-known gamblers. His partner, William (Big Bill) Devery, was long remembered as New York's most corrupt police commissioner, quite a heady status to have achieved in those rip-roaring gas-lit days.

Gambling at the ball parks became so flagrant after the turn of the century that some clubs began circulating private detectives through the stands to stop the practice and eject the gamblers. While this gave the game a cleaner appearance, it did not prevent betting on games in pool halls, barbers shops, taverns, and other places where venture capitalists gathered.

In his book of memoirs, Baseball As I Have Known It, veteran baseball writer Fred Lieb recalls an episode that occurred in 1913. Yankees manager Frank Chance disgustedly told Lieb and another writer that his first baseman, Hal Chase, was "throwing games on me." When Lieb reported this to his editor, he was told to "pass it up." Lieb suggests that Chase's shenanigans were common knowledge around the American League, but that nothing was done, except for Chase being dealt away from New York to the White Sox.

L-R: Frank Farrell, William Devery, Frank Chance, Hal Chase The notorious Hal Chase was a scintillating talent, so magical around first base that one team after another was willing to risk hiring him, probably figuring that a Hal Chase that gave you his all even 80 percent of the time was preferable to anybody else. This is another way of emphasizing how rare and how prized exceptional talent is. If you're temperamental, eccentric, abrasive, alcoholic, ethically dubious, but you can hit or pitch, your continued presence will be rationalized.

For those who saw him play first base, Hal Chase was forever the standard, sometimes approached, never equaled. He seems to have had mongoose qualities when it came to fielding bunts. Lieb claims Chase was quick enough to pick up bunts on the third-base side of the mound and nab runners at any of the three bases. Chase must have possessed remarkable agility (for fielding bunts and for staying out of jail, too). He was also something of an innovator in the field, being one of the first to play wide of the bag and one of the few who could execute the 3-6-3 double play with unerring skill. He was apparently good enough, too, to dump a game and leave behind suspicions that were clouded with doubt. You've got to be pretty damned adept at what you're doing to deliberately fluff a play and not leave your teammates squinting too sharply at you. Roger Peckinpaugh, then a young shortstop with the Yankees, recalled one of Chase's dubious maneuvers.

I remember a few times I threw a ball over to first base, and it went by him to the stands and a couple of runs scored. It really surprised me. I'd stand there looking, sighting the flight of that ball in my mind, and I'd think, "Geez, that throw wasn't that bad." Then I'd tell myself that he was the greatest there was, so maybe the throw was bad. Then later on when he got the smelly reputation, it came back to me, and I said, "Oh-oh." What he was doing, you see, was tangling up his feet and then making a fancy dive after the ball, making it look like it was a wild throw.

Like many notable rogues, Chase could be a charmer. He was, by all accounts, witty, intelligent, and personable, eminently likable. He was also described as having a "corkscrew brain." Given his apparent inability to think straight, New York, where he began his big-league career in 1905, was probably not the most ethically healthful place for Chase. The 22-year-old Californian hit the sidewalks of the big city running: along with his unprecedented glides and whirls around first base and an engaging personality that was animated by a winning smile, Prince Hal (yes, they did call him that) knew how to box, was a virtuoso with a pool cue, and a dead shot with a rifle. This suggests that whatever education he had included some time spent on the other side of the tracks, places where, if discussion of ethics ever came up, they centered on how best to live one's life around them.

L-R: Roger Peckinpaugh, Jimmy Ring, Christy Mathewson So this was no ingenuous rookie hitting the big time, no gullible bumpkin unstrapping his suitcase in the big city. Chase soon became a drawing card by dint of his spectacular glovework. And the young Californian with the bright smile but guarded eyes soon revealed his penchant for gambling. As a baseball celebrity and as one of the pets of high-stakes gambler and club owner Frank Farrell, he was made welcome. What intrigued the boys around the dens where optimism blows forever hot was Chase's predilection for betting on ball games, including some in which he was a participant. Now it would take a man with the moral fiber of a saint to whack out base hits and spear crucial grounders and pegs in a game in which his money was riding on the other team, as Chase's sometimes was. Occasionally, it was said, Hal shored up a sure thing by giving a teammate a piece of the action and then letting the man decide for himself where his best interests lay. Some teammates cooperated, some did not. Among the latter was a young right-hander named Jimmy Ring, a rookie teammate of Chase's on the 1917 Cincinnati Reds. When before a game that Ring was starting Chase offered to increase the weight of Ring's wallet if Jimmy would dilute his best efforts, Ring told him, "If you ever say anything like that to me again, I'll beat the livin' shit out of you." Jimmy was one tough bruiser from the hard-fisted precincts of Maspeth, Long Island, and so Chase just smiled and walked away.

That Chase's machinations were no secret was amply borne out later. After Frank Chance sent him to the White Sox, Hal jumped to the Federal League, and when that foredoomed enterprise folded up, joined Cincinnati in 1916. He led the league in batting that year with a .339 average and continued on as the Nijinsky of first base, when he felt like it, as teammates sighed, sportswriters chuckled or shook their heads, and fans went on buying tickets and going through the turnstiles with the faith of churchgoers. This time, however, Chase was performing his capers in the lengthening shadows of Judgment Day. The first of these shadows was cast by his Cincinnati, skipper, none other than the game's first genuine icon, Christy Mathewson himself. Hal was about to get his head caught in a couple of slamming Sinai tablets.

L-R: George Stallings, Ban Johnson, John Heydler, Heinie Zimmerman When George Stallings, Frank Chance's predecessor as Yankee manager, came right out and accused Chase of throwing games, Ban Johnson chastised him for staining the name of a top drawing card. When Frank Chance said the same thing, he was ignored. (Indeed, when Chance traded Chase to the White Sox, Frank Farrell was so outraged he soon canned Chance.) But when Christy Mathewson questioned Chase's honesty, people had to listen. Demigods speak in thunder. By 1918 the demigod had seen enough and reported to National League president John Heydler that Chase was throwing games. Hal got a reprieve on this occasion, however, for just as Heydler began his investigation of the matter, Mathewson joined the army and went overseas. With his chief accuser in the trenches of France, Chase was able to survive for another year. Baseball writer Fred Lieb reported that in an off-the-record conversation with Heydler, the league president said he believed Mathewson but lacked the proof to make the charge stand up.

Interestingly enough, Chase's final big-league year, 1919, was spent playing for John McGraw. Why McGraw decided to hire the shady rascal is a mystery, particularly in light of Mathewson's charges. It's true that the Giants needed a first baseman, and perhaps McGraw, with his sense of omniscience, felt that his mere presence would be injunction enough to intimidate Chase into honesty. But even John J. must have felt at times that having Chase on the team was like carrying around a parcel handed to you by an anarchist. As a reformer and a deterrent, McGraw failed. Not only was he unable to stop Chase from "funnying" up a game, but Hal's virus was apparently infectious. In mid-August, the Giants announced that both Chase and 3B Heinie Zimmerman had been suspended indefinitely. "Indefinitely" in this case meant permanently. Neither Chase nor Zimmerman, whom Hal may well have cajoled into some dubious investment opportunities, ever played in organized ball again, though no formal charges were ever filed against either man, nor did either man try to get back into the game.

Chase continued playing baseball, semipro, in Mexico, Arizona, and New Mexico until well into his forties, and those dazzling skills began to fade. One can only speculate what thoughts wwent through that "corkscrew" brain as he moved from one dusty town to another, being Hal Chase, Prince Hal, incomparable darling of New York fans, upon the rocky, hard-surfaced diamonds of mining towns and waystations, performing his 3-6-3 whirligigs for a few dollars under the broiling sun of the Southwest. If he had any regrets, he left them unrecorded. He died on May 18, 1947, in Colusa CA, age 64, leaving behind a legacy of smiles, charm, wizardry, and deceit–the Benedict Arnold of baseball.

Had baseball been more vigilant and decisive when it came to dealing with the Hal Chases in its midst, the greatest scandal in the history of American sports - the Chicago White Sox throwing the 1919 World Series - might never had happened.

"Craziest Mix-Up I Ever Saw" Baseball Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis suspended Babe Ruth and teammate Bob Meusel for 39 days at the beginning of the 1922 season amid huge public outcry against the move. Ruth and Meusel had gone on an unapproved barnstorming trip in the offseason.

Babe's first game after the suspension was against the St. Louis Browns at the Polo Grounds, where the Yankees played their home games before Yankee Stadium opened in 1923. Here's Babe's recollection of the game as told to Bob Considine in The Babe Ruth Story (1948). The Yankees met the Browns the day my suspension was lifted. I'll never forget that game. It was one in a million, for the Browns actually won it after the last man had been called out.

It was played at the Polo Grounds on a Saturday, and there was such a terrific turnout that the police shut the gates an hour before game time. A lot of fans came out to see Bob and me, but it was our second baseman, Aaron Ward, who provided the main thunder. He hit a home run with a man on base, giving us an early 2 to 0 lead on (P Urban) Shocker. Sam Jones was our pitcher. He gave up a run in the eighth but retired the first two men in the ninth, and we seemed to have the game won.

Then two pinch-hitters made good for the players at the bottom of the line-up. That brought up Johnnie Tobin, their fast lead-off man. Johnnie grounded down to Wallie Pipp at first, who tossed it over to Sam Jones, covering first base, and Umpire Ollie Chill thumbed Tobin out. We broke for the clubhouse while the fans in the lower stands tumbled out onto the field.

L-R: Aaron Ward, Sam Jones, Wallie Pipp But Jones hadn't made a clean catch of the ball. Pipp's throw hit Sam's glove, took a short bounce, and by the time Sam grabbed it securely, Tobin had crossed the bag.

(Lee) Fohl, coaching at first, squawked to Chill and finally went to the umpire behind the plate, who admitted that Jones hadn't caught the ball when it first struck his glove and that Tobin should have been ruled safe.

From then on there was the craziest mix-up I ever saw. Some of our players were already in the showers and thought it was a gag when they were told to return to the field. "Hey, I saw Chill call that man out," I squawked, and I had plenty of company.

In the meantime the fans were milling around on the ball field, and it took the special cops about 20 minutes to clear the field.

It still makes me froth to think what happened after that. Jones had cooled off and had lost his stuff by the time he returned to the rubber. There were a couple of blooper hits and bases on balls which tied the score, and then that big (Baby Doll) Jacobson came up with the bases filled and knocked a ball into the lower right-field stands.

The Browns scored six runs after their last man had been called out and beat us 6 to 2!

If ever there was a wild ball club it was us in the clubhouse that night. As for Jones, the loss of the game bothered him so much that he went on a ten-game losing streak immediately afterward.

I wasn't much help. While my suspension limited my season to 110 games, I fell off in all departments. My batting average sank from .378 to .315, and my home runs dropped from 59 to 35. That still was a lot of homers, but it wasn't good enough to keep my home-run title that season.

Our 1922 team wasn't a harmonious club, and looking back I'm really surprised we finally won. I had my arguments with Hug (Manager Miller Huggins) and so did (pitchers Waite) Hoyt, (Carl) Mays, and (Joe) Bush. The club knew that (Owner Tilly) Huston had no use for Huggins, and that didn't increase our respect for the little man.

The Yankees of that period were an odd club. I don't believe there ever was a gamer, more fighting team. We played up to the hilt in every game, but we had more than our share of night riders. We kept a couple of Jersey beer barons rich.

(General Manager Ed) Barrow hired a detective to make a Western trip with us and report back to him. The gumshoe posed as a great Yankee fan who was taking the trip as a sort of vacation. He seemed to know a lot of spots we had never heard of.

Fast Feller

Memories and Dreams: The Official Magazine of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

(Winter 2022), John Rosengren In 1946, his first full season after serving almost four years in the Navy during World War II, Bob Feller posted one of his finest performances. He won an MLB-best 26 games, 10 of them shutouts, most in themajors. He broke the modern major league record for strikeouts, fanning 348 (until it was later discovered Rube Waddell had struck out 349 in 1904). He posted a personal-best 2.18 ERA. His WAR was a dazzling 10.0.

"I don't think anyone is ever going to throw a ball faster than he does. And his curveball isn't human," the Yankees' Joe DiMaggio had said five years earlier. After going 0-for-4 against him on April 30, 1946, when Feller pitched his second career no-hitter, this one at Yankee Stadium, DiMaggio's opinion hadn't changed.

Feller also threw a slider, a sinker and, later in his career, a knuckleball. But it was his fastball that shaped his nicknames – Rapid Robert, Bullet Bob,the Heater from Van Meter – and powered him to immortality as one of the game's greatest pitchers.

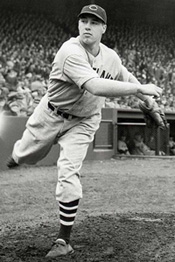

L-R: Bob Feller, Rube Waddell, Walter Johnson, Christy Mathewson Pitching his entire career for the Cleveland Indians, he led the American League in strikeouts seven times and finished with 2,581 career Ks, which was third-highest all time (behind Walter Johnson and Cy Young) when he retired in 1956. He won 20 games six times, including a major-league best 27 in 1940, and 266 over his 18-year career. (Had he not missed almost four seasons in his prime, it is easily projectable that Feller could have won 350 games and recorded 3,500 strikeouts).

He pitched three no-hitters and 12 one-hitters. He was the first pitcher elected to the Hall of Fame in his initial year of eligibility (1962) since Walter Johnson and Christy Mathewson in the Hall's inaugural class.

Born on a farm in Van Meter, Iowa, in 1918, Feller claimed he could throw a baseball father than 270 feet before he was 10 years old. Never bashful about his estimation of himself, Feller said: "By the time I was nine years old, I knew I could throw a baseball faster than anybody else."

He was pitching in the major leagues before he graduated high school, signed to the Indians by legendary scout Cy Slapnicka. On July 6, 1936, Feller appeared in an exhibition against the Cardinals. The second batter he faced, Leo Durocher, supposedly chided the youngster, "Keep the ball in the park, busher." Feller stuck him out on three fastballs. And in Durocher's next at-bat, the kid stuck out The Lip again.

Feller made his official MLB debut almost two weeks later on July 19, coming on in relief in the eighth inning and walking a batter, and made several more relief appearances before being entrusted with his first start on Aug. 23 against the St. Louis Browns. With his fastball on fire, he struck out 15, one short of Waddell's American League record. Before the summer ended, Feller tied Dizzy Dean's major league record of 17 Ks in a nine-inning game. Two years later, when he was still a teenager, he set a new record, mowing down 18 Tigers on the final days of the 1938 season, including Hank Greenberg twice.

Feller was only 23 years old when he enlisted in the Navy after the attack on Pearl Harbor. In the three previous seasons, he had led the league in wins (24, 27, 25), strikeouts (246, 261, 260) and innings pitched (296.2, 320.1, 343.0). He'd thrown the first Opening Day no-hitter: At Comiskey Park against the White Sox on April 16, 1940. He'd throw two more no-hitters before he was done – against the Yankees in 1946 and one against the Tigers in 1951. Those three no-hitters tied the career mark held by Cy Young and Larry Corcoran and stood as the record until Sandy Koufax threw his fourth no-hitter in 1965.

Feller, who was an All-Star four times before WWII and four times and after, had three 20-game winning seasons after his return from military service. He went 26-15 in 1946, 20-11 in 1947 and 22-8 in 1951 – his .733 winning percentage that season the best in the league.

"I just reared back and let them go," he told LOOK magazine in 1951. "Where the ball went was up to heaven."

Just how fast was Feller? Since he played before radar guns were de rigeur, it's hard to say. But his fastball so dazzled those who saw it – either from the batter's box or the stands – that several extraordinary attempts were made to measure its speed.

In 1941, a motorcycle was pitted against Feller's fastball in Chicago's Lincoln Park. Feller stood in the parkway wearing street clothes and shoes, without the benefit of throwing from a mound, while a Chicago policeman on a Harley-Davidson charged from behind toward a target 60 feet, 6 inches beyond Feller. As the motorcycle roared by at 86 mph, Feller reared and threw – though by the time he released the ball, the policeman had a 13-foot lead. Still, Feller's pitch easily beat the Harley to the target. The mathematicians calculated the speed of his pitch at 104 mph.

Five years later, in a 1946 exhibition at Griffith Stadium in Washington, D.C., Feller hurled several pitches through an Army contraption originally designed to measure the velocity of artillery shells. A catcher set up behind the wooden-frame machine that straddled the plate. One of Feller's pitches, instead of going through the opening about the size of a strike zone, struck the frame and knocked loose a two-by-four. But he threw enough strikes to allow the Army ordinance equipment to measure his speed. In newsreel footage of the event, narrator Ed Herlihy gushes: "Photoelectric cells register the unbelievable delivery of the ball, which rockets along at a world record speed of 98 and six-tenths miles per hour.

While that may have been the fastest pitch recorded at the time, if the ball's speed had been measured when it left Feller's hand – as is done these days – instead of when it crossed the plate, the speed would have registered even higher."

The thought of facing him was enough to unnerve even the game's greatest hitters. Ted Williams said he would start thinking about Feller three days before he had to bat against him. Williams called Feller "the fastest and best pitcher I ever saw during my creer. He had the best fastball and curve I've ever seen."

A Kid Named Berra

He's a Diamond in the Rough - And Vice Versa

Arthur Daley, Baseball Digest June 1949 Reprinted in Baseball Digest May/June 2024 Just about the time the war was ending, Larry MacPhail, then the president of the Yankees, conferred with Master Melvin Ott, then the manager of the Giants—which should show you what ancient history all this is. The rambunctious redhead had under contract four catchers of various degrees of ability and experience.

"I'd like to buy one of your catchers, Larry," said Master Melvin. "In fact, the Giants are willing to pay $50,000 for one of them."

"Which one?" asked MacPhail, suddenly cautious.

"I'd like a guy you probably don't even know you got," continued Ottie. "He's a kid named Berra."

MacPhail thought awhile and slowly shook his head. "Not Berra," he said, "he's not for sale."

L: Young Yogi Berra. R: Carmen and Yogi Berra Perhaps there are some fans who promptly would think the astute MacPhail merely was showing the prescience which bespeaks genius. Stop jumping at conclusions, please. Laughing Larry was telling the story on himself in Havana a couple of seasons ago.

"If the truth must be told," he chuckled, "I'd never heard of Berra, but I figured if he was worth fifty grand to Ottie, he must be worth fifty grand to me. That's why I turned him down. But one day I'm in my office, and the girl comes in to announce that Mr. Berra is outside to see me. 'Berra?' I say to myself. 'That must be the kid Ottie was trying to buy.' So I tell her to show him in.

"So I waited for my first look at the prize package which was worth $50,000. The instant I saw him, my heart sank, and I wondered why I had been so foolish as to refuse to sell him. In bustled a stocky little guy in a sailor suit. He had no neck and his muscles were virtually busting the buttons on his uniform. He was one of the most unprepossessing fellows I ever set eyes on in my life. And the sailor suit accentuated every defect." MacPhail sighed and continued. "Since then, though, I've never regretted the move."

Berra is just as unique a character as he looked the first time Laughing Larry saw him. His honest moniker is Lawrence. But everyone calls him Yogi—as well as other less kindly names. However, Yogi is one of nature's noblemen with an honest heart that beats beneath that rough exterior. No ballplayer is ridden as cruelly or unmercifully as he. But he accepts it all with a homely grin. He hasn't the quick wit to retort in kind. So he laughs it all off and has won the deep affection—sometimes it almost amounts to admiration—of his teammates and the rival players.

The perfect description of him was supplied by Milton Gross, who called him "The Kid Ring Lardner Missed." Yogi is a pure throwback to the ballplayers of the "You Know Me, Al" Lardner era. The writers go around from day to day asking each other: "Did you hear the latest Berraism?" They coined a word, "Berraism," to set him aside in a separate category.

Perhaps the most wonderful one he ever pulled was the night in St. Louis, Yogi's hometown, when fans set aside a separate night in his honor. They showered him with gifts, and then came one of the most terrifying moments in Berra's life. He had to approach a microphone and make a speech. They hauled him up there. Yogi shuffled up in a daze. Even his vocal cords were paralyzed. He spoke one sentence. It was a classic.

"I want to thank all you fans," he blurted, "for making this night necessary."

Yogi hits a tremendously long ball—when he hits it. But he has a pernicious habit of swinging at bad balls. No one tried harder to cure him of that habit than Bucky Harris. One day Bucky sent him in as a pinch hitter, but first he cautioned:

"Don't swing at a bad ball, Yogi," he warned. "Wait for it to be in there. When you get up to the plate, think, Yogi, think."

Yogi struck out and came back to the bench muttering.

Harris bent an ear in his direction and started laughing uproariously. What Yogi was saying was this: "How can a guy be expected to think and bat at the same time?"

Bucky was deeply enamored with him. Before the 1947 World Series someone asked him if Yogi would be nervous. He howled. "Yogi nervous?" he chortled. "He has about as much emotion as a fire hydrant."

But Berra was nervous. The Dodgers stole everything from him except his chest protector.

"A guy doesn't get into a World Series every day," he protested. "After all, I'm human, ain't I?" No one had ever thought of it before.

However, Berra is a whale of a ball player. The Yankees won a pennant with him as a catcher even though his stubby fingers were so short that he had to paint them so the pitchers could distinguish the signs. Then he was an outfielder last season (a presentable one, too), now is a catcher again.

Bill Dickey, one of the greatest catchers of all time, is busy instructing him in the rudiments of the position. As Yogi describes it: "Dickey is teaching me all his experience." Berra used to take a step one time and no step the next. The Arkansas Traveler is at least making him consistent.

Yogi grew up across the street from Joe Garagiola of the Cardinals in St. Louis. In the sandlots Berra was a pitcher, Garagiola a catcher. They have been inseparable companions ever since, with Joe serving as Yogi's best man at his wedding two months ago. Perhaps we had better move in the Cards catcher as spokeman for the defense.

"Yogi married a beautiful and wonderful girl," he said with earnest simplicity. "But she couldn't have married a nicer, more gentle or finer man in this world than Yogi Berra."

The defense rests.

Tom Seaver's Circuitous Road to the Mets

David Schoenfield, espn.com, September 2, 2020

Fifty-one years later, it might still be the greatest baseball story ever told. The Miracle Mets of 1969, never having finished above .500, going from ninth place in 1968 to the World Series title. The hapless, bumbling, laughingstock New York Mets, most famous for the time Marv Throneberry hit an apparent game-winning triple only to have missed first base, with the Mets instead losing the game. Those luckless, atrocious Mets, whom Casey Stengel explained had selected a certain catcher in the expansion draft because they needed somebody to prevent the ball from rolling to the backstop.

That's how the Mets were born and, boy, were they bad. They lost 120 games that first season in 1962 and followed up with seasons of 111, 109 and 112 losses. In 1966, they climbed out of last place for the first time -- all the way up from 10th place to ninth. The fans in Queens loved them nonetheless. Even though the Mets lost 95 games that year, they finished second in the major leagues in attendance.

The transformation from lovable losers to champions began in 1967. It began with Tom Seaver.

Tom Seaver with USC and the Mets. The story of how Seaver landed with the Mets is a little miracle in itself. The Atlanta Braves had drafted the Southern California right-hander in the secondary phase of the January draft in 1966, a part of the draft that no longer exists and was reserved for players previously drafted who didn't sign. The Los Angeles Dodgers had drafted Seaver in the 10th round in 1965, but a Dodgers scout named Tommy Lasorda refused to meet Seaver's $70,000 asking price. Seaver returned to school.

Seaver and the Braves reached a deal in late February for a $40,000 bonus. USC's spring season had already started, however, and under baseball's rules, a team couldn't sign a player if his college season had begun. Commissioner Spike Eckert nullified the contract. Seaver then tried to return to school, but the NCAA declared him ineligible, even though he had yet to accept any money.

It was a classic Catch-22 situation. Seaver's dad threatened a lawsuit. Eckert, in an unprecedented move, set up a special lottery. Any team willing to match Atlanta's $40,000 bonus could participate, but the Braves were banned from signing Seaver for three years. Only three teams chose to get involved in the Seaver sweepstakes: the Philadelphia Phillies, Cleveland Indians and Mets. The Mets won the lottery.

Eckert explained his decision was "for the interest of the boy and the public. The youngster previously signed a contract with another club in good faith only to learn he had been improperly contracted," Eckert said. "It was not his fault that the contract was invalidated."

Did the Mets know what they were getting? It's perhaps noteworthy that only three teams thought he was worth that $40,000 bonus, though that was a sizable bonus for the time, more than most of the first-round picks would receive that June. Seaver had been lightly scouted in high school in Fresno CA, but he was just 5-foot-9 and 160 pounds as a senior in 1962. He spent the next year working in a packing plant and joined the Marine Corps Reserve. After a year at Fresno City College, he transferred to USC.

So while Seaver was only the 20th pick in the January phase, it was apparent he was an excellent prospect. The Fresno paper called him a "fireballing right-hander." It's possible that Seaver's bonus demands scared some teams away. His dad also thought Seaver's military commitment might have been an issue. "The Braves were the only club to go after him," Charley Seaver said, "possibly because of his military status."

But it's also possible some teams hadn't seen Seaver and that even though he had gone 10-2 with a 2.47 ERA for USC, his fastball didn't impress. Years later, Baseball America quoted a veteran scout from the area who said of Seaver: "Some clubs wouldn't give him more than $4,000 because he had a below-average fastball. But he pitched against a team called the Crosby All-Stars just before the draft and was facing active major leaguers. He struck out 12 in five innings."The Fresno Bee didn't mention that game, but it did mention one outing for USC early in 1966 when Seaver threw five perfect innings against the San Diego Marines. The paper also said the Dodgers had reportedly offered Seaver $50,000 to sign in 1965.

Seaver was an immediate star in New York. He spent 1966 in the minors and reached the Mets in 1967, when he went 16-13 with a 2.76 ERA and won National League Rookie of the Year honors. He went 16-12 with a 2.20 ERA in 1968 as the Mets climbed out of the cellar. Still, after going 73-89, they weren't expected to do much in 1969, the first year the leagues were split into divisions.

All the Mets did in 1969 was win the World Series. Tom Seaver was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1992.

Always a Hit

Memories and Dreams: The Official Magazine of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

(Spring 2022), Jerry Crasnick The achy knees that dogged Tony Oliva through the second half of his career cried out for attention and prompted his teammate, roommate and close friend Rod Carew to embark on more than a few recuse missions - fetching ice to dull Oliva's pain.

But for the first eight seasons of his big league career, it was American League pitchers who were looking for help against Oliva, whose legendary skill at the plate made him one of the game's most celebrated hitters.

Elected to the Hall of Fame in December by the Golden Days Era Committee, Oliva grew up in a family of 10 children in the town of Pinar del Rio, Cuba, a major tobacco growing region and a center of the cigar industry. His father, Pedro, was a successful semipro ballplayer who turned to farming and grew tobacco, mangos, oranges and other crops on a 150-acre plot.

Much of the family's land was seized by the Castro regime in the late 1950s, but baseball was a constant, and it wasn't uncommon for the Oliva clan to choose up sides and play three games on Sunday.

L-R: Tony Oliva, Rod Carew, Kent Hrbek Tony Oliva's given name was Pedro Oliva II, but he assumed an alternate identity out of necessity. After Twins scout "Papa Joe" Cambria signed him out of a Havana tryout, Oliva lacked the documentation to get from Cuba to Spring Training in Florida. So he borrowed his brother Antoine's birth certificate as a step toward acquiring a passport. From that time forward, he would be known as "Tony."

Oliva overcame a language barrier, several bouts of homesickness and some culture shock on his way to stardom. He hit .342 in 337 minor league games in Wytheville, Va., Charlotte, N.C., and Dallas-Fort Worth before cracking the Twins' Opening Day roster in April 1964. He led the American League that season with 217 hits, 109 runs, 43 doubles, 374 total bases and a .323 average to win the AL Rookie of the Year Award and his first of three career batting titles.

Oliva thrived thanks to a "see the ball, hit the ball" mantra and a flair for making solid contact. He was selected to eight All-Star teams, logged a .304 career batting average and struck out just 645 times in 6,301 big league at-bats. He topped out at 55 walks in a season, preferring to let the bat head fly on pitches at his shins or at the letters. His quick hands, keen eyes and sweet swing prompted some writers to wax poetic.

"Watching Tony Oliva hit a baseball is like hearing Caruso sing, Paderewski play the piano, or Heifetz draw a string across a bow," wrote Phil Elderkin of the Christian Science Monitor.

The elite pitchers of Oliva's day found him problematic as a rule. Oliva hit .320 against Luis Tiant, .344 off Jim Palmer, .356 vs. Sam McDowell, .365 off Tommy John, .429 vs Dean Chance and .467 against Rollie Fingers. He launched seven homers in 112 at-bats against Mel Stottlemyre and eight in 93 at-bats off Catfish Hunter.

But after a severe knee injury in 1971, playing in the field became difficult - even for a man who won a Gold Glove Award in 1966. He underwent eight knee surgeries through the years and missed almost an entire season in his prime, transitioning to a full-time designated hitter role at age 34. He retired three years later.

Oliva was a baseball savant with the capacity to both hit and teach. After his retirement in 1976 he spent 15 years dispensing encouragement and common sense advice as a coach in the minors and majors for the Twins. Kent Hrbek, the local boy-made-good for the Twins, had an out-of-body experience in Spring Training of 1979 when he went down to the batting cage in Melbourne, Fla., and encountered his baseball icon.

"To me, it was like watching God walk around the clubhouse," Hrbek said. "If Tony told me to go out and stand in the freeway, I would have done it. I idolized the heck out of the guy. Anything he told me would go in one ear and then stay there."

Baseball fans in Minnesota and surrounding states are already making plans for Induction Day in July. That includes Hrbek, who has reserved a spot for his 42-foot motor home at a campground near Cooperstown. He can't wait to make the trip with his girlfriend and see his hero shaking hands, posing for photos and signing autographs with a smile.

"The only difference now is, when he signs 'Tony Oliva,' he has to put 'HOF' on the ball," Hrbek said.

|