Baseball Short Stories - 13

Coast to Coast

Memories and Dreams: The Official Magazine of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

(Fall 2022), John Rosengren The storied rivalry between the Giants and Dodgers was born in New York, dating back to an encounter in 1889 between the New York Giants and the Brooklyn Bridegrooms in a best-of-11 championship series. But the baseball rivalry between Brooklyn and New York - separate cities until 1898 - goes back even further.

More than 150 years later, interest in games played between the Dodgers and Giants has remained similarly strong, even with the rivalry relocated to California.

In the beginning, the feud took shape from the distinct and contrasting characters of Manhattan and Brooklyn. They pitted glitz against grit: Broadway, Park Avenue and the Upper East Side versus Flatbush, Bed-Stuy and Prospect Park. Dodgers fans disliked the urbane elitism of the Giants following; Giants fans disdained the blue-collar language of the Dodgers faithful.

The move to the West Coast changed the complexion but not the intensity of the rivarly, accentuated once again by the varying natures of the two host cities and the animosity intrinsic between the capitals of Northern and Southern California.

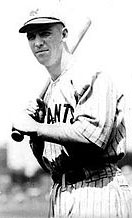

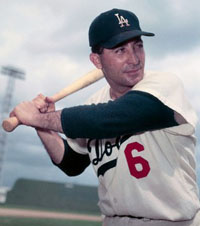

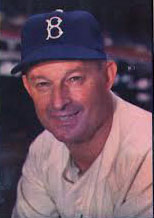

L-R: Carl Furillo, Charles Ebbets, Joe McGinnity "Los Angeles and San Francisco had long sustained a mutual disregard - hatred blended with a tinge of jealousy for what one town possessed that the other did not," David Plaut wrote in Chasing October: The Dodgers-Giants Pennant Race of 1962.

"We hated the Giants," said Carl Furillo, an All-Star outfielder who played his entire career with the Dodgers. "We just hated the uniform."

Not surprising then that passion lurked whenever the Giants and Dodgers played, dating back to the first encounter in 1889. A winner-take-all intensity charged the ballpark every time the two teams squared off. Giants players felt the surge the moment they arrived in enemy territory. The atmosphere and tradition pushed the players to compete at a higher level.

Strong personalities had stoked the rivalry over the decades. Brooklyn owner and president Charles Ebbets resented that his star pitcher, Joe "Iron Man" McGinnity, had joined the Giants in 1902 and wanted in every way to beat them. John McGraw, who became the Giants' manager that year, targeted Ebbets with frequent insults at the park and in the press. Ebbets lobbied the league (unsuccessfully) to punish McGraw. The stakes escalated in 1914 when McGraw's former teammate turned nemesis, Wilbert Robinson, became the Brooklyn skipper, a position he held for the next 17 years. The two rivals didn't so much play games as wage battles.

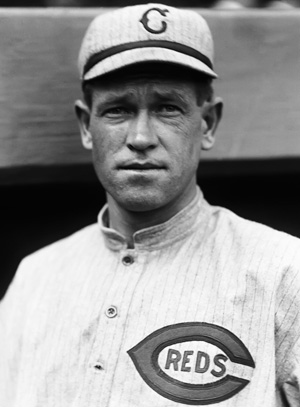

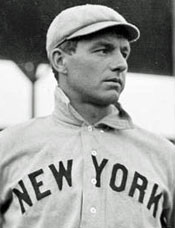

L-R: John McGraw, Wilbert Robinson, Bill Terry After the Giants won the World Series in 1933 and the Dodgers finished 26.5 games back, McGraw's successor, Bill Terry, responded to a reporter's question about the Dodgers prospects in 1934, "Brooklyn? Is Brooklyn still in the league?"

The Dodgers retaliated by defeating the Giants in the final two games of the season to spoil New York's pennant chances while Brooklyn fans waved "We're still in the league" banners at the Polo Grounds.

Seventeen years after that, Dodgers manager Charlie Dressen provoked the same revenge when he announced midseason in 1951, "The Giants is dead." That resuscitated New York with a winning spree (39 of 47 games) that wiped out the Dodgers' 13-game lead, the coup de grace coming off Bobby Thomson's bat in the last inning of the three-game playoff with the "shot heard 'round the world."

They replayed the script on the opposite coast 11 years later, the Dodgers again ceding a large lead down the stretch in 1962 and facing the Giants in a three-game tiebreaker to decided the pennant winner. After splitting the first two games, the Dodgers led the third, 4-2, going into the ninth, but the Giants scored four runs in the top of the inning to win the game and the pennant.

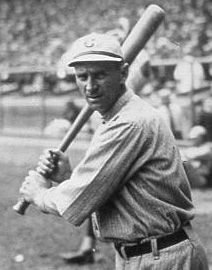

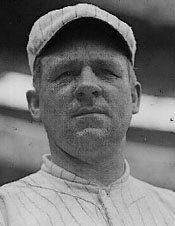

L-R: Charlie Dressen, Sal Maglie, Jackie Robinson When the two teams played one out of every seven games against each other - 22 times each summer - the spikes came up, the fastballs shrieked inside and the benches often cleared. In 1951, Giants P Sal Maglie, known a "The Barber" for the close shaves he regularly gave batters, knocked down the Dodgers' Jackie Robinson. Jackie bunted Maglie's next pitch down the first base line, and when the pitcher bent over to field it, Robinson smashed into him with a vengeance that emptied the benches.

Four years later, Maglie again brushed back Robinson, who again bunted. This time, "The Barber" avoided fielding the ball even though Jackie slowed to give him the chance to reach it. Instead, Robinson knocked over Giants 2B Davey Williams, who was covering first. Alvin Dark, then the Giants' shortstop, bowled over Robinson at third base later in the game, jarring the ball loose from Robinson's grip, and the two grappled.

In 1953, Ruben Gomez, famous for pitching inside, plunked the Dodgers' Furillo, who was contending for the battle title, in the wrist. Figuring Leo Durocher had ordered the pitch, Furillo charged the Giants' manager. In the brawl that followed, someone stepped on Furillo's hand, breaking a bone, and he had to sit out the next 10 days (though he did end up winning the battle title with his .344 average).

L-R: Alvin Dark, Ruben Gomez, Leo Durocher But the moment that epitomized the intensity and marked the apex of violence occurred at Candlestick Park on Aug. 22, 1965, with the two teams once again vying for the pennant. After both the Dodgers' Sandy Koufax and the Giants' Juan Marichal had been warned by the plate umpire not to throw any more brushback pitches, a return throw by Dodgers C John Roseboro buzzed Marichal in the batter's box from behind. Startled, Marichal - who said the ball nicked his ear - wheeled, saw Roseboro advacing on him in full gear and brought his bat down on the catcher's head, inciting a 14-minute brawl. Ultimately, Marichal was fined $1,750 - a record amount at the time - suspended for eight playing dates and barred from pitching in Los Angeles in early September. In the end, the Dodgers edged the Giants for the pennant.

In an unexpected twist to their story, the two men eventually forgave one another and became friends. When Marichal joined Los Angeles in 1975 at the end of his career, Roseboro appealed to Dodgers fans to give him a chance.

Juan Marichal (27) hits C John Roseboro as P Sandy Koufax comes in. In 2021, the historic rivalry continued to thrive with all of its complexity and controversy. For most of the regular season, the Giants held off the Dodgers - though the two teams were tied for first on September 4 - and finally won the division by a single game. That set up a dramatic NLDS that went the distance, the Dodgers leading, 2-1, in the ninth inning of Game 5. The Giants managed to get the tying run on base. With two outs and an 0-2 count, Dodgers P Max Scherzer threw a slider. Wilmer Flores checked his swing, but upon appeal, the first base ump signaled strike.

And, once again, the two teams split the sweet and bitter tastes of victory and defeat.

Royal Treatment

Seventy-five years ago, Jackie Robinson took his first steps toward the big leagues in Montreal.

John Powers, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum 2021 Yearbook

Stengel, DiMaggio, and Mantle

The New York Yankees of the 1950s: Mantle, Stengel, Berra, and a Decade of Dominance,

David Fischer (2019) 19-year-old Mickey Mantle joined the Yankees for the 1951 season and immediately electrified the baseball world. Manager Casey Stengel saw the Commerce Comet as the replacement for the aging Joe DiMaggio in center field.

Although the Yankees were winning, the mood in the locker room was not always harmonious. The relationship between DiMaggio and Stengel continued to deteriorate to the point that they now ignored each other’s existence. New York beat writers who traveled with the club had no difficulty picking up on the palpable tension between player and manager. When reporters approached Stengel to question him about the volatile situation, he replied: “So what if he doesn’t talk to me? I’ll get by and so will he.” The absolute discord between the two would hit a sour note during the July 7 game at Boston’s Fenway Park. It was the dog days of summer, and Casey’s club was flagging. The Yankees were only one game behind the Chicago White Sox, but they had lost four of their previous five games. Their play was uninspired. The three-day All-Star break would begin at the conclusion of the next afternoon’s game against the Red Sox, and Stengel admitted his team was fatigued. “Four or five of these players are dead tired,” he explained.

Stengel’s diagnosis of his team proved prophetic. In the first inning, Bobby Doerr hit an easy popup that DiMaggio misplayed, coming up short on the shallow flyball that dropped for a hit, allowing two runs to score. The next batter, Billy Goodman, hit a high flyball to right-center that DiMaggio couldn’t chase down, loading the bases. From Stengel’s point of view, those were two plays that a younger version of DiMaggio would have easily made. When Clyde Vollmer followed with a grand slam home run, the Yankees were deep in a six-run hole, which prompted the New York manager to make a fateful decision. He dispatched rookie Jackie Jensen out to center field. When Jensen reached center he informed DiMaggio that Casey was pulling him from the game. With a large Fenway Park crowd looking on, DiMaggio trotted from the field with his head down.

L: Casey Stengel and Joe DiMaggio; R: DiMaggio and Mickey Mantle Once again, Stengel had displayed a complete lack of regard for DiMaggio’s public stature. At least, that was how Joe perceived events. The skipper’s decision to make the move and replace the aging superstar in the middle of the game strained an already acrimonious relationship. Following the 10–4 loss to the Red Sox, DiMaggio boiled with rage in the clubhouse as teammates looked at one another in stony silence. DiMaggio’s left leg was ailing, Stengel explained, that’s why he removed him from the game. Nobody was buying what Casey was selling. The Yankees lost again the following afternoon, too. More than any other team, the Yankees needed the brief rest provided by the All-Star break. They had the look of a tired team and they had limped into the midsummer respite, both literally and figuratively, having lost five of their last six, including a three-game sweep in Boston at the hands of the Red Sox. The Yankees sank into third place behind the first-place White Sox and second-place Red Sox.

Mantle had fallen into a prolonged slump and was optioned to AAA Kansas City where he regained his confidence.

Toward the end of the summer of 1951, the Yankees and the resurgent Cleveland Indians—winners of 13 games in a row to start the month of August—played leapfrog with each other in the standings as the White Sox and Red Sox faded badly. Rookie Gil McDougald was the team’s leading hitter, and with DiMaggio not up to snuff, catcher Yogi Berra supplied most of the punch with Gene Woodling and Hank Bauer chipping in admirably. To fortify the offense, Mantle returned to fuel New York down the stretch. The kid returned to the Yankees on August 20, never to spend another moment in the minors. Now wearing the more familiar jersey number 7, Mantle batted .284 with six homers and 20 RBIs in the team’s remaining 27-game charge. ... With the Indians leading the Yanks by only one game, on September 16 and 17 Cleveland was scheduled for its final visit of the season to the Stadium. To face the right-handed aces of the Cleveland staff, Bob Feller and Bob Lemon, Stengel chose Allie Reynolds and Eddie Lopat. For the opener of the two-game set, 68,760 people, the largest crowd of the season, jammed into the Stadium to see if the defending champion Yankees could stay in the race. Feller, one of the great pitching stars in the history of the game, was 22-7 going into the game, and was one of three pitchers, along with Early Wynn and Mike Garcia, to win 20 or more games for the Indians. Reynolds was pitching the best baseball of his career, and on this afternoon he pitched brilliantly, allowing only five hits and one run. The Yanks were leading, 3–1, and in the bottom of the fifth Mantle, batting third in the lineup, doubled, and Berra, batting fourth, received an intentional walk as Feller preferred to pitch to DiMaggio. DiMaggio, burning inside because Stengel had dropped him to fifth in the order, lined a ball into the left-center field alleyway for a two-run triple and a 5–1 Yankees lead, finishing Feller and the Indians for the day. After the game a pile of Western Union telegrams were delivered to DiMaggio’s locker, congratulating him on his clutch hit. “Now when I get a hit,” said DiMaggio with contempt, “they send me telegrams.” New York was back in first place by percentage points over Cleveland in their tug-o-war for the AL pennant flag. The second game of the series pitted Lopat, vying for his 20th win of the season, against Indians sinkerball pitcher Bob Lemon, who already had posted 17 wins on the year and always gave the Yanks difficulty. This was another pitchers’ battle. The score was tied at one run apiece. It was the bottom of the ninth inning. Phil Rizzuto was at bat. DiMaggio was on third base. Rizzuto took Lemon’s first pitch, a called strike, and argued the call with the umpire. That gave him time to grab his bat from both ends, the sign to DiMaggio that a squeeze play was on for the next pitch. But DiMaggio broke early, surprising Rizzuto. Lemon, seeing what was happening, threw high, to avoid a bunt, aiming behind Rizzuto. But with Joltin’ Joe bearing down on him, Rizzuto got his bat up in time to lay down a bunt. “If I didn’t bunt, the pitch would’ve hit me right in the head,” Rizzuto told the New York Times. “I bunted it with both feet off the ground, but I got it off toward first base.” DiMaggio scored the winning run. Stengel called it “the greatest play I ever saw.” As the winning run scored, Lemon angrily threw both the ball and his glove into the stands. With 12 games to go, New York now led by one full game. ...

The Yankees claimed their third consecutive pennant, a 98-65 record lifting them five games ahead of the second-place Indians, but Joe DiMaggio, 36, his body aching, was no longer the Jolter—he slumped to .263 with only 12 home runs and 71 runs batted in. Yogi Berra was the Yankees’ most dangerous hitter now, with 27 homers and 88 RBIs. Mantle, in his rookie season, batted .267 with 13 homers and 65 RBIs in 96 games. Another newcomer, third baseman Gil McDougald, the only New York regular to hit over .300, was the AL’s Rookie of the Year, with a .306 batting average, 14 homers, and 63 RBIs. ...

The Yankees faced the New York Giants in the World Series.

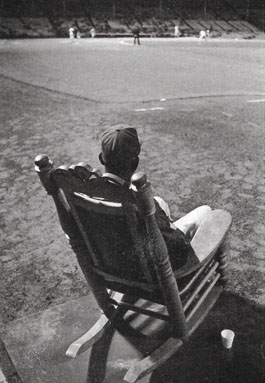

The Yankees won the second game as southpaw Eddie Lopat throttled the Giants attack with his slow curves, scattering five hits through nine innings for a 3–1 victory, but Mantle wasn’t around to help celebrate. He started the game with a bunt single and ended in a room at nearby Lenox Hill Hospital in Manhattan, with his father in the adjoining bed. In the fifth inning, Willie Mays led off with a flyball to right center. Mantle had been covering extra ground all season, covering for the aging DiMaggio, in the twilight of his career. According to several sources, Stengel had instructed Mantle earlier to “take everything you can get over in center. The Dago’s heel is hurting pretty bad.” Mantle ran hard for the ball. DiMaggio did, too. This was the World Series, and the entire country was watching. An instant before Mantle was to glove the high fly, DiMaggio called, “I got it.” In reverence, the rookie right fielder pulled up at the last second, turned on the outfield grass to slow his momentum, and fell to the turf, crumpled in a heap. The 19-year-old speedster had stepped on a drainpipe and torn ligaments in his right knee. DiMaggio caught the ball, but Mantle was finished for the Series. He had to be carried off the field and rushed by cab to the hospital for surgery—the first of a series of leg injuries that robbed him of much of his speed and plagued him throughout the rest of his career. As teammate Jerry Coleman said, The Mick had “the body of a god. Only Mantle’s legs were mortal.”

L: DiMaggio catches fly as Mantle collapses; R: Mickey watching the Series from his hospital bed. On the way out of the stadium, Mutt Mantle tried to help his son into the taxi that would take him to the hospital, but when Mickey placed his hand for support on his father’s shoulder, Mutt collapsed from the weight, his spine already ravaged by Hodgkin’s disease. The two watched the rest of the World Series from their adjacent hospital beds. Mickey had surgery and was sent home to heal. Mutt was given a grim prognosis and succumbed the following May. He was 39 years old. Mutt Mantle was denied watching most of his son’s major-league career, but at least he saw Mickey switch-hit in a World Series, right-handed in the first game, left-handed in the second.

The Giants won Game 3 to take a 2-1 lead on the Yankees. Heavy rains delayed the Series for two days.

When play resumed, the Yankees were able to return to their Game 1 starter, Reynolds, on three days rest. He was sharper this time around, and atoned for his first-game defeat by going the distance in a 6–2 victory, striking out seven, as the Yankees evened the series. DiMaggio, held hitless in 11 at-bats in the first three games, found his groove and paced the Yankees’ attack with a single and a two-run homer.

The Yankees won the Series in six games.

The 1951 World Series would end up being the finale for Joe DiMaggio’s baseball career. He finished the 1951 regular season with an average of .263, by far the lowest mark of his career. He hit .261 in the World Series, but contributed three extra-base hits and five RBIs. The double he lashed to right field off New York Giants 20-game winner Larry Jansen in the sixth game was to be his last hit. The Yankee Clipper was nearing his 37th birthday when World Series play ended. Following 13 seasons with the Yankees, he had posted a career average of .325 and 361 home runs. However, he felt he wasn’t able to play up to his own standards anymore. Still, he ended the season up to his standards in one way: with a ninth World Series title in 10 tries. Not long after the Series ended, DiMaggio arranged a meeting with team owners Dan Topping and Del Webb. He complained his body was aching and acknowledged his skills had deteriorated. He told them that he didn’t think he could play anymore, so he had decided to retire. “I’m finished,” he admitted. Topping asked Joe to think it over during his barnstorming trip through Korea and Japan, hopeful that DiMag would reconsider. Joe agreed, but in his heart, he knew his decision had been made. Webb told DiMaggio not to worry about the money, and promised him the same $100,000 salary for next year. He offered to have the contract drawn up and sent over for his signature. DiMaggio demurred. It wasn’t about the money, he promised. He didn’t want to play baseball anymore. Several weeks later, Life magazine published a scouting report on the Yankees that included a sad perspective of DiMaggio’s skills. Andy High, a Dodgers scout, who had followed the Yankees for the final month of the season, had compiled most of the report. When the Dodgers didn’t win the pennant, their front office presented the scouting report to the Giants in a show of National League unity. After the Giants won the Series opener, manager Leo Durocher raved about the scouting report, saying, “It’s great. I never saw a report like it.” The report couldn’t win the Series for the Giants, but its disclosure embarrassed DiMaggio more than any other player. It read:

DiMaggio’s friends knew that his pride surely would not let him play now that the erosion of his skills had been publicly exposed. And early in December, shortly after his 37th birthday, he phoned Topping, saying that he wanted to come to New York to announce his retirement. But he agreed to Topping’s request for another meeting. That’s when Topping and Webb played their last card: Manager Casey Stengel’s plan to use him on a part-time basis, with DiMaggio determining when he would play. Joe appreciated the offer, but could not agree to be a part-time player. His retirement was final except for the announcement. On the morning of December 12, at the club’s Fifth Avenue office suite in the Squibb Tower, the newsmen were handed a statement announcing Joe DiMaggio’s retirement. Joe was there, of course, with Topping, Webb, and Stengel alongside him. “I can no longer produce for my ball club, my manager, my teammates, and my fans the sort of baseball their loyalty to me deserves,” said a tearful DiMaggio. “Until yesterday,” Webb told DiMag, “we had still hoped you would stay. But, since you didn’t change your mind, it’s a sad day, not only for the Yankees, but for all baseball as well.” When the questions began, one newspaperman naturally asked, “Joe, why are you quitting?” “I no longer have it,” he replied.

Over in another corner of the Yankees offices other baseball writers had Casey Stengel surrounded. “Who’s your center fielder now?” one wondered. “The kid,” the manager said. “Mickey Mantle.”

L-R at Joe DiMaggio's retirement: Yankees GM George Weiss, Casey Stengel, Joe, Del Webb, Dan Topping A Paige Out of History - 1

Don Amore, Baseball Digest, January/February 2022

At age 59, Satchel Paige threw three scoreless innings in one of the most improbable achievements in baseball history.

The stories must have been apocryphal. Had to be, right? Hammering nails with a fastball? Heaving a ball 400 feet on the fly? Sending his fielders back to the dugout and then striking out the side on nine pitches?

Or were they?

When Leroy "Satchel" Paige joined the Kansas City Athletics in September of 1965 at the age of 59, he regaled his new, young teammates with stories, like the one about his legendary control. Throwing strikes over a matchbook? C'mon.

"Rene Lachemann used to love it," said A's outfielder Tommie Reynolds. "Lach was catching him, and he'd put down a gum wrapper and Satch would throw it over that gum wrapper. He'd throw a breaking ball over it. Wherever he put it, Satchel threw the ball right over it."

"He was something," Lachemann said. "I'd catch him on the side a lot. I'd fool around with him a lot and I'd say, 'I heard you threw strikes over a gum wrapper.' He said, 'Put one down," and sure as spit, he threw it right there to it."

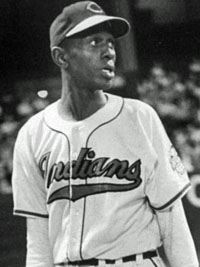

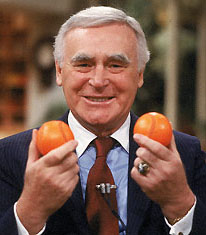

No one was quite sure what to make of it when Charles O. Finley signed Paige, the legendary Negro leagues star, on September 10, 1965. Paige had last pitched in the majors in 1953–12 years earlier–and he was two months past his 59th birthday, though Satch liked to tell people a goat ate the Bible that had his birth certificate tucked in it.

It was a publicity stunt, to be sure. But it produced one of the most remarkable feats and magical nights in baseball history: September 25 1965, the night Sachel Paige nowed down major-league hitters for three innings.

L-R: Satchel Paige with Cleveland; Charles O. Finley, Satchel with Kansas City "I didn't give a damn if I made an out," said Jim Gosger, 79, who went 0-for-2 against Paige. "You were facing someone of this stature who'd been around so long and he was a gentleman. An absolute gentleman. It's something you just never forget."

As hard to believe as the tallest of Satch's tall tales, the ageless Paige pitched three scoreless innings in a major-league regular-season game, allowing only one hit.

"Unheard of," said Lee Thomas, who played first base for Boston. "That doesn't happen."

The 10th-place A's were on their way to losing 103 games, and dying at the turnstiles. Finley would try any gimmick he could dream up to draw a few fans. Manager Haywood Sullivan refused to comment on Paige's signing, other than to confirm Finley's directive that he was to start two weeks later on the 25th.

Not allowed by baseball's racial barrier to play in the major leagues during his prime, Paige finally made his big league debut for Veeck at age 42 in 1948, and he was no stunt. He went 6-1 for the American League champion Cleveland Indians and pitched in the World Series. Later, with Veeck's St. Louis Browns he was an All-Star at ages 45 and 46. Then he pitched a few more years in the minors.

In 1965, Paige needed money. He had not pitched long enough to qualify for the MLB pension and his wife, LaHome, was expecting their eighth child. They had written to 20 teams asking for a job in the game. Meanwhile, Paige signed with promoter Abe Saperstein, the Harlem Globetrotters owner who had been a Negro leagues investor, to make personal appearances. In June, Paige threw batting practice before a benefit exhibition game between the St. Louis Cardinals and Detroit Tigers at Busch Stadium. After one batter reached the wall, Paige stopped throwing BP fastballs and began using his assortment of offspeed pitches and offbeat deliveries, and none of the major-league hitters could get the ball out of the infield.

On September 8, Finley had his young shortstop, Bert Campaneris, play every position, and it drew 21,000 fans to Municipal Stadium, where the A's were barely drawing 1,000 fans for home games that late in such a lost season. Two days later, he signed Paige, who lived in Kansas City and agreed to pitch three innings for $3,500.

"I'll need three or four days to get really sharpened up," Paige told reporters.

The idea was for Paige to be a sort of coach and cheerleader for that month, and it would count toward the service time he needed to qualify for the $125-per-month pension. He'd joke with players about his age, repeat his famous 10 rules to live by, and other Satch-isms.

"Sure, I ejoyed it," Reynolds, 80, said. "I used to go out to the bullpen, which I didn't often do because I was a [position] player, but I didn't mind going to the bullpen when Satch was there. I heard a lot of stories, he kept it lively. He'd tell us, 'If you see a bear, don't help me, help the bear.' After the game, he wouldn't take a shower because, he said, 'water rusts iron.'

"Just being around Satch, it was like being with history."

To be continued ...

A Paige Out of History - 2

Don Amore, Baseball Digest, January/February 2022

Latin Legend

Memories and Dreams: The Official Magazine of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

(Spring 2022), Phil Rogers Minnie Minoso blazed a trail for generations of Latin American stars who followed.

His most valuable asset, however, may have been pure determination.

"Don't quit," fellow Cuban and All-Star pitcher Jose Contreras said he was told by Minoso during a big league career that, like Minoso's, began late. "Don't leave the field if you think you can still play."

Raised in the sugar cane country outside Havana, Saturnino Orestes Armas Minoso dearly loved his homeland - and learned tenacity during arduous work in the fields. His skill at baseball, however, put him on the path to a different life.

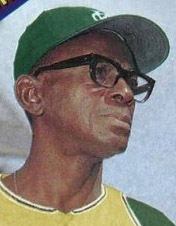

L: Minnie Minoso, R: Jose Contreras Major leaguers are fond of saying they will play until someone tears the uniform off their back. But the charismatic Minoso almost lived that boast. He's known for having played in the major leagues over five decades, thanks to cameos with the White Sox in 1976 and 1980, but it was in the Mexican League where his love for baseball shown the brightest.

He was released by the White Sox at midseason in 1964 and headed to Mexico that winter. He sometimes served as a player-manager but was still active as a player in '73, when he turned in 120 games as a first baseman/outfielder. He was most likely in his 50s when that season ended, although listed officially at 47 with a birthdate of Nov. 29, 1925.

"I went (to Mexico) for one year and stayed for 10," Minoso said late in his life.

Among stops in the Negro leagues, minor leagues, American League, National League and the Mexican League, Minoso likely totaled more than 4,000 professional hits.

But Minoso was more than just numbers. He blazed a trail for players from Latin America in the same way Jackie Robinson opened the door for Black players. The first dark-skinned Latin player to appear in the AL or NL, he allowed young players in Cuba, the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico to dream about playing on the best teams in the world.

"To me, Minnie is a legend," Contreras told The New York Times. "He was one of the reasons I started playing baseball when I was a kid. I wanted to be like him. He was one of our best representatives, our Jackie Robinson."

Minoso revered Cuban native Martin Dihigo, who was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1977. It was easier to follow Minoso's career in the 1940s and '50s than it had been Dihigo's in the '20s and '30s, which allowed him to set an example at a time more Latin Americans were finding their way to the big leagues.

L: Orlando Cepeda, R: Roberto Clemente Orlando Cepeda, inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1999, remembers fellow Puerto Rican Roberto Clemente idolizing Minoso. "He was everybody's hero," Cepeda said. "I wanted to be Minoso. Clemente wanted to be Minoso."

A catcher as a teenager and mostly a third baseman for the Nego National League's New York Cubans, Minoso was in right field for his American League debut with the Cleveland Indians on April 19, 1949.

He was a complete player who finished his career with a .299 batting average, 195 home runs and 216 stolen bases, and built a .387 career on-base percentage by always being a tough out. In his 14 full-time seasons in the American League and National League, he drew 812 walks while striking out only 580 times.

On an afternoon at Yankee Stadium in May 1955, Minoso was hitting cleanup. With men on second and third with one out in the first inning, he dug his spikes into the dirt intent on bringing home two runs. The pitch from Bob Grim, a 20-game winner and Rookie of the Year in '54, slammed into the left side of Minoso's head, breaking his helmet.

He was diagnosed with a skull fracture the next day, but somehow returned to the lineup two weeks later. He suffered another skull fracture in 1962 after colliding with the brick outfield wall while playing for the St. Louis Cardinals. He also broke his right wrist that season. It was the beginning of the end for him as a highly productive player.

Minoso had made Chicago his full-time home by then and died happily in 2015, living near Lake Michigan with his wife, Sharon Rice, and their son, Charlie, whom Minoso fathered while in his 60s.

"He wanted to chase the American dream," Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Bseball Museum, told The New York Times. "He laid down that foundation to so many others, because they knew they would have the opportunity to play this game."

Exit Dick Williams

Glenn Dickey, Champions: The Story of the First Two Oakland A's Dynasties–and the

Building of the Third (2002) The Oakland Athletics, managed by Dick Williams, had won the World Series in 1972, upsetting the Cincinnati Reds despite the meddling of volatile owner Charles Finley.

The 1973 playoffs were vintage Oakland A's: great pitching, controversy swirling around owner Charlie Finley, a fight in the clubhouse, and, finally, a dramatic victory.

The team's win in the World Series the previous year hadn't convinced the skeptics about the A's; the Baltimore Orioles were 11-10 favorites in the American League Championship Series. There certainly were reasons to like the Orioles. Like the A's, they had great pitching–with Jim Palmer, Mike Cuellar and Dave McNally–and they had the edge in postseason experience, having played in three World Series in the four previous years.

With Vida Blue, Catfish Hunter, and Ken Holtzman, the A's had three 20-game winners; but they had also lost CF Billy North because of a sprained ankle near the end of the season. From his spot at the top of the batting order North was often the catalyst for the A's offense.

Baltimore won the first game of the ALCS 6-0 as Palmer outpitched Blue, but the A's bounced back with a 6-3 win over McNally.

The predictable Finley controversy came a couple of days later, with the series having switched to Oakland for what was scheduled as an afternoon game. Rain had started the day before and continued into Monday. After looking at a weather forecast that predicted still more rain, American League President Joe Cronin postponed the game for a day.

Finley cornered Cronin in the tunnel leading to the dressing room and started screaming at him. Cronin tried to tell him that that wasn't the place to "discuss" his decision, but Finley continued screaming as several members of the media, a few A's players, and Williams all watched, with emotions varying from amusement to embarrassment.

Finley was angry because the postponement would allow Palmer, who had won 22 games and led the league with an ERA of 2.40, to come back for the fourth game on three days rest, which was the norm for starters at the time. Cronin's decision stood, and the matter became academic when the rain continued well into the evening.

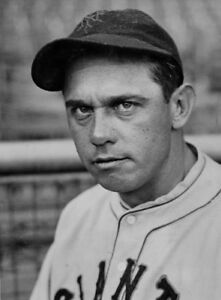

DIck Williams, Charles Finley, Vida Blue, Rollie Fingers The A's won Game 3 2-1..

The next day, after knocking out Palmer in the second, the A's seemed to be on their way to clinching the ALCS as they took a 4-0 lead into the seventh behind Blue. But then Blue lost it, giving up four runs to tie the game and getting only one out before he was rellieved by Rollie Fingers. In the next inning Fingers had one of his few failures, giving up the game-winning homer to Bobby Grich.

That day, Blue was in the middle of a typical A's upheaval in the clubhouse. Fingers talked disgustedly of how the A's had the Orioles by the throat but let them get away. Blue Moon Odom thought he was putting the blame on Blue, Odom's friend, and he started yelling at Fingers. "If you don't give up the home run to Grich, we don't lose the game." Soon, Fingers and Odom were brawling, though other players quickly separated them.

The A's won ALCS Game 5 3-0 to advance to the World Series once again.

The 1973 World Series would be an exciting one, as dramatic in its own way as the 1972 Series, again extending to the full seven games. But as so often happened in the Finley years, the action on the field was overshadowed by the off-field antics of the A's bombastic owner.

The rules of professional baseball specify that only players on a major league roster on August 31 are eligible for postseason play. Because Finley had sold reserve C Jose Morales to the Montreal Expos on September 18, the A's had only 24 players who qualified. The number was reduced to 23 when North sprained his ankle. His injury would keep him out of the World Series, and he quickly became a non-person to Finley.

Said North, "I have a picture in my office of me sitting between Charlie Finley and Dick Williams as Finley told me I wouldn't even be able to sit on the bench for the Series. Teams do that all the time for injured players, and I'd had a pretty good season. I'd led the league in stolen bases and runs scored until I was hurt."

North would sit in the third deck at Shea Stadium for the third game, but no more. "I thought, 'I don't need this,' so I went home."

The A's had petitioned to add designated runner Allen Lewis and reserve infielder Manny Trillo to their roster for the ALCS games, and Baltimore had agreed, so the A's had a full 25-player team. The Mets, the National League champions, were not as agreeable as the Orioles had been. They OK'd the addition of Lewis to the roster (since nobody other than Finley ever thought he did the A's any good), but refused to allow Trillo to be added. The A's would play the Series with only 24 men.

Before the first game in Oakland, Finley ordered his public address announcer to tell the fans that the Mets had refused to allow Trillo to be added to the roster. The announcement was obviously intended to be a public embarrassment to the Mets, and commissioner Bowie Kuhn issued a statement reprimanding Finley.

The first game was a pitching duel between left-handers Holtzman and Jon Matlack, but it was Holtzman's hitting that was the big story. Designated hitters weren't used in any of the Series games, which seemed to be a disadvantage for the A's because their pitchers were not accustomed to batting. But in the third, Holtzman hit a two-out double down the left-field line. Then, when Mets 2B Felix Millan allowed a Campaneris grounder to go through his legs, Holtzman scored. Campaneris stole second and scored on a single by Joe Rudi. That run was the difference in the eventual 2-1 A's win.

The next game, which is still remembered while the other games from that Series have faded out of memory, came to be known as the Mike Andrews game. It started a classic Finley controversy.

The Mets led 6-4 going into the bottom of the 8th.

Williams put in pinch-hitter Andrews for the good-fielding, poor-hitting Ted Kubiak; Andrews remained in the game at second base. Andrews, in the final year of his eight-year major league career, had been injured during most of the season and had started only 15 games at second, being used mostly as a designated hitter. He was not prepared to play in the field, but he was there when Milner grounded to second for what should have been the third out. The ball went through Andrews' legs, and two runs scored. Jerry Grote then grounded a ball to Andrews' right; this time, he handled the grounder but threw wide of first base, allowing the Mets to score the fourth run of the inning.

In his box along the third-base line, Finley called team physician Dr. Charles Hudson as the inning finally ended. When Andrews entered the dressing room, he was told to report to orthopedist Dr. Harry Walker, who had been summoned by Dr. Hudson after Finley's phone call. After the examination, Finley had a long talk with Andrews and then showed the press a statement from Dr. Walker that read: "Mike Andrews is unable to play his position because of a bicep groove tencosynotitis of the right shoulder. It is my opinion that he is disabled for the rest of the year." The doctor had signed the report and so had Andrews, under the words "I agree to the above."

Finley would later claim that Andrews had signed the statement in exchange for a guaranteed 1974 contract. Andrews told UPI that Finley "had threatened to destroy me in baseball" if he didn't sign the statement.

Andrews' version of events had much more credibility because Finley's motive was obvious: he wanted to be able to put Trillo on the roster. Even though they should have been accustomed to Finley's bizarre behavior, Andrews' teammates were shocked when they learned of his "suspension" just before boarding their flight to New York for the third game of the Series. At practice the next day, at (Captain Sal) Bando's suggestion, they wore black patches with the number 17, Andrews' number on their sleeves. (Reggie) Jackson hinted at stronger action, saying there might be a player boycott. Holtzman later recalled: "We had voted on the plane to boycott if Andrews was't reinstated. And you know that bunch, they would have done it."

Fortunately, the players didn't have to follow through on their threat. After meeting with Andrews, commissioner Kuhn reinstated him, ending Finley's attempt to activate Trillo. Said Kuhn: "The handling of this matter by the Oakland club [read: Finley] has had the unfortunate effect of unfairly embarrassing a player who has given many years of abale service to professional baseball."

Finley accused Kuhn of making his statement to the media before even sending a copy to the A's owner: "It is my ballclub, my money, and I don't appreciate anybody telling me how to spend my money to run my business. I don't think the commissioner treated us fairly in turning down our request. He's talking about embarrassing Andrews. We're not out to embarrass Andrews. But I sure as hell was embarrassed by what the commissioner did."

The Athletics won Game 3 2-1.

The fourth game was an easy 6-1 Mets triumph, noteworthy primarily because Williams used Andrews as a pinch-hitter in the eighth. The New York fans showed their opinion about the controversy by giving Andrews a standing ovation. Williams had the satisfaction of embarrassing Finley, who had to stand with the crowd and weakly applauded.

The A's won the World Series in seven games.

Their victory was quickly forgotten after the game, however, when Williams announced on national television that he was quitting as the A's manaager. It was no surprise to his players; Williams had told them before the third game of the Series that he would be quitting.

Because of the timing, even his players assumed that the Andrews incident had led to Williams' decision; but in truth, his decision had been made earlier in the season. If there was one incident that precipitated it, it was probably one that involved Jackson. In September, Jackson had pulled a muscle and Williams wanted to use him as a designated hitter. Finley, probably trying to keep Jackson's statistics down for salary negotiation purposes, instead ordered Williams to put Jackson on the bench. Williams had secretly been talking to the New York Yankees who were about to make a managing change. "The Andrews case was the final straw," he said, "but I was ready to quit before then. I wanted to go to New York."

But Williams was still under contract, and Finley wouldn't release him unless the Yankees compensated the A's with either P Scott McGregor or OF Otto Velez. New York wouldn't part with their best minor league talent, so the Yankees made their managerial change–from Ralph Houk to Bill Virdon–and Williams went home to Florida. Finley finally released Williams from his contract so he could take over the California Angels in midseason, but the Angels, who went 36-48 under Williams that year, were not the Yankees. "I guess Charlie won, after all," said Williams.

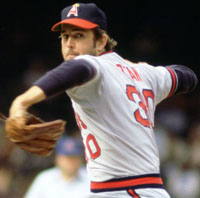

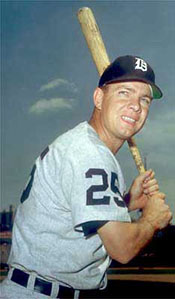

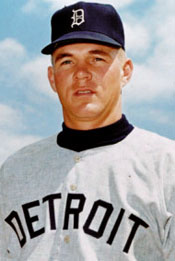

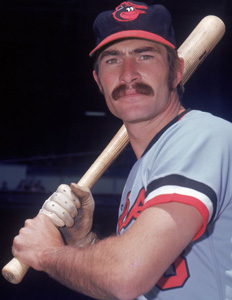

Numbers King

Nolan Ryan's Strikeout Achievements Still Fill the Record Books

Scott Pitoniak, Memories and Dreams: The Official Magazine of the Hall of Fame (Winter 2021)

|