|

Baseball Short Stories - 11

My Greatest Day in Baseball: Honus Wagner

My Greatest Day as told to John P. Carmichael and other noted sportswriters (1945)

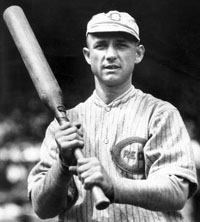

John Henry "Hans" Wagner, whose name is written large in golden baseball letters, was rated the greatest shortstop of all time, and once was called "the best ball player that ever trod in spiked shoes" by John J. McGraw.

When a fellow has played 2,785 games over a span of 21 years it's not the esiest thing in the world to pick out a single contest and say it was his best or that it gave him his biggest thrill. But I was never sharper than in the last game of the World Series our Pirates played with the Detroit Tigers of 1909, and I never walked off any field feeling happier.

I regard that final game with the Bengals as tops because it meant the end of a grand fight against a bunch of real fighters. I'm still willing to testify that the club of Hughie Jennings and Ty Cobb, of "Wahoo Sam" Crawford and Donie Bush, of Davy Jones and George Moriarity, was a holy terror. And it tickles my vanity to think the Pirates outbattled and defeated them.

Cobb stole two bases in the series, but I was lucky and got six. Cobb made six hits, I made eight.

Ask Ty what happened the day he stood on first and yelled at me, "Hey, Kraut Head, I'm comin' down on the next pitch." I told him to come ahead, and by golly, he did. But George Gibson, our catcher, laid the ball perfect, right in my glove and I struck it on Ty as he came in. I guess I wasn't too easy about it, 'cause it took three stitches to sew up his lip. That was the kind of a series it was from start to finish. Fred Clarke, our manager, told us we'd better sharpen our spikes since the Tigers would be sure to, and we took him at his word. We were sorta rough, too, I guess.

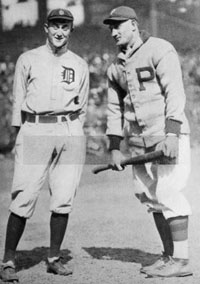

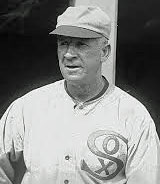

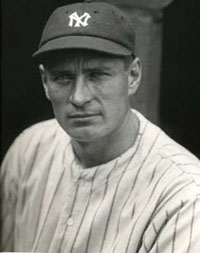

L-R: Ty Cobb and Honus Wagner at the 1909 World Series, Hughie Jennings, Fred Clarke Cobb surprised the Pirates by playing an unusually clean series, but some of the others weren't so careful.

The trouble started in the first game. Both sides had their jockeys warmed up. The Tigers let us have it and we gave it back to 'em with interest. There was a jawing match on nearly every pitch, and it was a good thing we had two of the greatest umpires who ever worked - Bill Klem and "Silk" O'Loughlin. They were young fellows then, but they knew their business and kept us in line. At least there weren't any riots.

In that first game, Fred Clarke hit a home run off Big George Mullin, who was Detroit's best pitcher that year. I followed Clarke at the plate, and I could see that Mullin was boiling, and anxious to get back at us. I always stood pretty far away from the plate, but this time took every inch I could, figuring Mullin would throw at me. I wasn't wrong. He laid his fast ball right in my ribs. Of course, you can't say a thing like that is deliberate, but our boys reckoned it was, and from that minute the rough-housing was on.

We came into the final game tied up at three apiece. It was played in Detroit, and the night before, the Tiger rooters hired two or three bands to play in front of our hotel and keep us awake, but (player-manager) Clarke fooled 'em by taking us all out to the tavern along the lake shore.

We knew our pitcher was going to be Babe Adams, the kid who had won two of our three victories. Babe was hardly old enough to shave, but Clarke had a hunch on him all along. I'll never forget the look on Adams' face when I told him Clarke wanted him to pitch the opener. He asked me if I wasn't fooling and I told him I wasn't and he hadn't better fool, either, when he got on the mound. What a job he did for us.

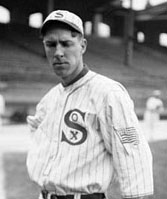

L-R: Babe Adams, "Wild Bill" Donovan, Tommy Leach , George Moriarity I guess I don't have to tell you what the feeling was that day. "Wild Bill" Donovan, who started for the Tigers, lived up to his name and we got two runs off him in the second. Mullin came in to pitch in the fourth and couldn't find the plate, either. There were two walks and two singles, giving us two more. In the sixth I got my only hit, but it ws a three-bagger that drove in Clarke and Tommy Leach, and I kept coming and crossed the plate when Davey Jones made a bad throw from the outfield. We certainly didn't need the run we picked up in the seventh, but it made us eight, and with Adams pitching perfect ball that was the score 8 to 0. But it's far from being the whole story.

On my hit Jones kicked the ball into the overflow crowd, trying to hold it to a double under the ground rules, but O'Loughlin saw him and wouldn't allow it. Another time there was a close play at first and the Tiger runner hit Bill Abstein, our first baseman, in the stomach with his fist. Abstein folded up and Ham Hyatt had to take his place. Another Tiger slid into second and cut Jack Miller on the head and leg. Bobby Byrne, out third baseman, banged into Moriarity so hard that Bobby had to leave the field with a broken ankle, and George, who concealed his injury until the next inning, went to the doctor to have 11 stitches put in his knee. Talk about "bean balls" - they were flying around everybody's head all afternoon.

This Is My Story of the Black Sox Series

The ringleader of the infamous plot, the first baseman of the team which exploded baseball's dirty business with the game's worst scandal, breaks his silence to speak for the first time.

Arnold (Chick) Gandil as told to Melvin Durslag, Sports Illustrated, September 17, 1956 A lot of you young readers have probably heard of the Black Sox scandal from your dads or granddads. Eight of us Sox were accused of throwing the 1919 World Series to Cincy. We were taken into court in Chicago, tried and acquitted. But organized baseball banned us for life.

To start with, I think I should recall to you the main characters involved.

First, there was Charles Comiskey, the White Sox owner. He was a sarcastic, belittling man who was the tightest owner in baseball. If a player objected to his miserly terms, Comiskey told him: "You can take it or leave it." Under baseball's slave laws, what could a fellow do but take it? I recall only one act of generosity on Comiskey's part. After we won the World Series in 1917, he splurged with a case of champagne.

Comiskey's manager was William (Kid) Gleason, who had been our coach in 1918 and became manager in 1919 when Clarence (Pants) Rowland resigned. He was a tough little guy, and he had a hard time trying to keep peace among the malcontents on our club. But most of the players liked him and gave him their best.

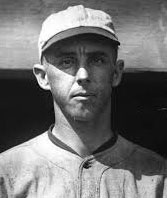

L-R: Chick Gandil, Charles Comiskey, Kid Gleason, Eddie Cicotte For all their skill, the White Sox in 1919 weren't a harmonious club. Baseball players in my day had a lot more cut-throat toughness anyway, and we had our share of personal feuds, but there was a common bond among most of us – our dislike for Comiskey. I would like to blame the trouble we got into on Comiskey's cheapness, but my conscience won't let me. We had no one to blame except ourselves. But, so help me, this fellow was tight. Many times we played in filthy uniforms because he was trying to keep down the cleaning tab.

Most of the griping on the club centered around salaries, which were much lower than any other club in the league. Eddie Cicotte, for example, had won 28 games in 1917 and still was making only $6,000 a year. Joe Jackson, a great hitter, was earning just a little more. I had been making $4,500 a year for the past three seasons. Only one man on the club was drawing what I'd call a decent salary, Eddie Collins, who had finagled a sharp contract in coming to the Sox from the Philadelphia Athletics. He was making about $14,000 a year. Naturally, Collins was happier with Comiskey than we were. So when the opportunity came in 1919 to pick up some easy change on the World Series, Collins, though a key man, wasn't included in our plans.

Where a baseball player would run a mile these days to avoid a gambler, we mixed freely. Players often bet. After the games, they would sit in lobbies and bars with gamblers, gabbing away. Most of the gamblers we knew were honorable Joes who would never think of fixing a game. I had always considered "Sport" Sullivan as one of those gamblers until that September day in 1919 when Sullivan walked up to Eddie Cicotte and me as we left our hotel in Boston. As I recall, we were four games in front the final week of the season, and it looked pretty certain that the pennant was ours.

I was kind of surprised when Sullivan suggested that we get a "syndicate" together of seven or eight players to throw the Series to Cincinnati. The idea of taking seven or eight people in on the plot scared me. I said to Sullivan it wouldn't work. He answered, "Don't be silly. It's been pulled before and it can be again." He said he was willing to pay $10,000 each to all the players we brought in on the deal. Considering our skimpy salaries, $10,000 was quite a chunk, and he knew it.

Cicotte and I told Sullivan we would think it over. The money looked awfully good. I was 31 then and couldn't last much longer in baseball. Cicotte and I tried to figure out first which players might be interested. And of those who might be, which ones would we care to cut in on this gravy. We finally decided on LF Joe Jackson, 3B Buck Weaver, CF Oscar Felsch, SS Swede Risberg, Eddie Cicotte, our leading pitcher; Fred McMullin, a utility infielder; Claude Williams, who was perhaps a better pitcher than Cicotte; and, finally, myself, the first baseman – not that we loved them, because there never was much love among the White Sox. Let's just say that we disliked them the least.

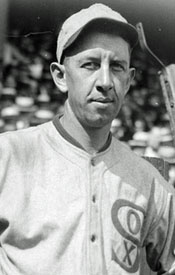

L-R: Joe Jackson, Buck Weaver, Oscar Felsch, Swede Risberg I met Sullivan the next morning and told him I could close the deal only if the players got their money in advance. He explained it would take a little time to raise all that cash so quickly but said that when he got it he would contact me in Chicago. As we parted, he told me that no player was to yap about the fix to other gamblers.

When the White Sox returned to Chicago for their final games of the season, Cicotte brought a friend of his to see me, a former big league pitcher named Bill Burns. Somehow Burns had got wind of our negotiations with Sullivan; one of our players must have talked. Burns asked that we definitely not accept Sullivan's deal until he could contact a rich gambling friend in Montreal. He said he could top any offer.

Cicotte and I called a meeting of the players that night and told them about Burns. Weaver piped up, "We might as well take his money, too, and go to hell with all of them." I personally disliked and distrusted Burns and said that we should stick with Sullivan. But I was overruled by the others who voted at least to listen to Burns's proposition when he returned from Montreal.

Later in Chicago I got word from Sullivan that he was bringing a friend from New York to sew up the deal. Sullivan introduced his friend as "Mr. Ryan," but, having met this man two years before in New York, I recognized him as Arnold Rothstein, the big shot gambler. His plan was this: We were to try our best to win the first game behind Cicotte, who was the league's leading pitcher. The White Sox were rated as 3-to-1 favorites in the Series. A win in the first game would boost the price higher. We were then to lose the Series at our convenience. At that time, a World Series was decided by five out of nine games instead of the four-out-of-seven system used today.

Rothstein said nothing until we asked for our $80,000 in advance. He asked calmly, "What's to assure us you guys will keep the agreement?" We offered him our word. He answered, "It's a weak collateral." The deal was about to fall apart when Rothstein came up with a compromise. He would give us $10,000 in advance and pay the remaining $70,000 in installments over the first four games, each payment amounting to $17,500.

We asked Sullivan and Rothstein to come back in an hour. I got the gang together and we decided to accept the deal. Rothstein returned and gave us ten $1,000 bills. When the gamblers left we entrusted the money with Cicotte until it could be changed inconspicuously. He put the bills under his pillow. At Rothstein's insistence, we had given our solemn word that no other gambler would be tipped off, but as soon as he left, we agreed to take any money we could get from Burns, too.

The next day I got a telephone call from Jake Lingle, the Chicago reporter who was later to be murdered by gangsters. Lingle said he heard the Series was fixed. "Where did you hear that crazy story," I said and hung up. I now began to worry. That night Sullivan paid me a visit. He was mad. He said that someone had yapped to Chicago gamblers about the fix. The price on the Sox had suddenly begun to drop. We had a hot argument that came close to turning into a fist fight. We both apologized, and an agreement was made for Sullivan to make the cash payments after each game to a friend on mine.

L-R: Fred McMullin, Claude Williams, Eddie Collins, Arnold Rothstein By the time we arrived in Cincinnati to open the Series the rumors were really flying. Even a clerk in a stationery store, not recognizing me as a ballplayer, told me confidentially, "I have it firsthand that the Series is in the bag." Waitresses and bellhops were talking the same way. Reporters were buzzing about, asking questions.

We were now convinced that every move on the field would be watched like a hawk and we were beginning to sweat. Burns and a friend, the prize-fighter Abe Attell, came to see Cicotte and me at the hotel. They asked that we arrange a meeting with the gang – which we did grudgingly. Attell took the floor and produced a telegram which read, "Will take you in on any deal you make. Will guarantee all expenses." It was signed, "A.R." Attell identified A.R. as Arnold Rothstein. The players exchanged looks. Obviously the telegram was faked, and Attell and Burns knew nothing of Rothstein's private deal with us. We walked out of the room.

This was the last of our group meetings with any gamblers. But now our troubles were just beginning. That night, the eve of the Series, several players got threatening phone calls. I must have had five during the early part of the evening. Many of them – maybe all of them – came from cranks, but they still left me creepy. Cicotte was so upset that he left the hotel about midnight and took a long walk. I don't think he slept an hour all night.

I had just fallen asleep when Sullivan knocked at my door and awakened me. He said excitedly that a couple of the players had told him the deal was off. I said to him, "Well, maybe it is." He replied, "I wouldn't call it the best policy to double-cross Rothstein." Deep down, I knew he was right. In my nervous state I got mad at Sullivan and told him to get out. I sat on the edge of the bed, trying to think. I truthfully wanted to go to our manager, Kid Gleason, and tell him the whole story, but I knew it wouldn't be that simple. I realized that things were too involved by now to try to explain.

I guess some of the others must have felt the same way, because the next morning I was called to a meeting of the eight players. Everyone was upset and there was a lot of disagreement. But it was finally decided that there was too much suspicion now to throw the games without getting caught. We weighed the risk of public disgrace and going to jail against taking our chances with the gamblers by crossing them up and keeping the $10,000. We were never remorseful enough to want to return the ten grand to Rothstein. We gambled that he wouldn't dare do anything to us since he was in no position himself to make a fuss over the cash. Our only course was to try to win, and we were certain that we could.

But when we trotted out on the field that day for the opener, we were still a tense bunch of ballplayers. And, as if things weren't bad enough, some joker in the stands yelled to Cicotte, "Be careful, Eddie. There's a guy looking for you with a rifle." Cicotte wasn't worth a wooden nickel in that opening game. He was knocked out of the box in the fourth inning when Cincy scored five runs. The Reds were unstoppable that day. When Cicotte was lifted in the fourth with the Reds leading 5-1, Gleason sent in Roy Wilkinson. The Cincy batters slugged him, too, just as they did our next pitcher, Grover Lowdermilk. Cincinnati got 14 hits that day and beat us 9-1.

Rumors of a fix began to circulate right away, and, though I didn't see Comiskey, I heard he was running around like a wild man, trying to track down information. What the wiseacres didn't know was that our original agreement with Rothstein was to try to win the first game.

That night I got more threatening phone calls. I'll never know whether they came from screwballs or from gamblers. I half expected a visit from Sullivan or one of his men, but I imagine things were hot for them, too. By this time I'm sure they knew the deal was off, especially since our collection man didn't show up after the game to try to get the first installment of the $70,000.

The White Sox made 10 hits in the second game against four for Cincinnati, yet we were beaten 4-2 when we should have won easily. In the fourth inning, with no score, we had runners on second and third with one down, but I grounded into an out at the plate and Risberg popped up to kill our chances. In the last of the fourth our pitcher, Williams, hit a wild streak, gave up three walks and a triple to give the Reds a 3-0 lead. They stretched it to 4-0 in the sixth, but we made two in the seventh when Risberg and Schalk scored on a wild throw by Greasy Neale, the Cincinnati right fielder who later became a pro football coach.

After the game the cynics made quite a thing of the six walks issued by Williams, and there were rumors that he wasn't following his catcher's signals. But nothing was said about Neale's wild throw, or some dumb base running by Edd Roush, the Cincy center fielder, who was caught in a trap and tagged out after trying to go to second.

The pressure eased when we came back to Comiskey Park for the third game and Dickie Kerr threw a shutout for a 3-0 win. I batted in our first two runs in the second inning with a long single to center. We made our third run on a triple by Risberg, who then scored on a slick bunt by Schalk.

That night I was paid an unexpected visit by Burns, who was in a panic. He and some other gamblers, going on the assumption the Series was fixed, had bet heavily on the Reds. Now they had their doubts. Burns said that if I could assure him that the players would go along with the fix, he would guarantee me $20,000. Since I personally didn't feel that Burns could guarantee me 20 cents, and since I was troubled with enough outside pressure as it was, I told him I wasn't interested. Meanwhile, the threatening calls got so heavy that I had to quit answering the telephone.

Cicotte went to the mound in the fourth game and allowed only five hits, but we got only three and were beaten 2-0. Both of the Cincy runs were scored in the fifth inning, partly due to two errors by Cicotte. One was probably my fault. Eddie fielded an easy roller and threw wide to first, permitting the runner to move to second. When the next batter singled to left center, and Jackson threw to the plate to try to cut off a run, I yelled to Cicotte to intercept the throw. I felt we had no chance to get the man at home but could nail the batter now trying to reach second. Cicotte juggled the ball and all hands were safe. The next man then doubled, and Cincy had both its runs.

Well, you can imagine all the gossiping that took place that night. Everyone talked of Cicotte's two errors, but no one even mentioned that he had allowed only five hits. After listening to all the talk in the hotel lobby, Gleason called a meeting of the players. He asked if there were any truth to the rumors he had been hearing. We who were involved with gamblers got all huffy about this; the players who were not kept quiet. Gleason was happy to let the matter drop, but Comiskey was now convinced that we were out to throw the Series. He suspected the whole club.

With the Reds now leading three games to one, we came back with Williams in the fifth game against Hod Eller, who was one of those fellows who could be either real bad or real good. This day he was good. He had a mean shine ball that had us missing all over the place. He struck out the side in two straight innings – and half of those he fanned were never in on our plot. Williams allowed Cincy only four hits that day, three coming in the sixth inning in which the Reds scored four runs. But before Eller was through with his shine ball, he struck out 9 batters and shut us out 5-0. Felsch got the blame for that loss. He had thrown wild after fielding a Texas leaguer in the sixth inning and later chased a long fly to the fence which he couldn't get and it went for a triple. When Collins booted one later, permitting the fifth run to score, the experts must have thought that he was in on the fix, too.

We went back to Cincinnati for the sixth game which we won 5-4 behind Kerr, after we had overcome a 4-0 Cincy lead. This was the only game to go into extra innings. In the 10th, Weaver doubled and I drove him home with a single for the winning run.

Though Cincy now led the Series 4-2, we honestly felt we had hit our stride and would have no trouble taking the next three games. We were even more confident the next day when Cicotte won his third start easily, 4-1. We breezed in this game, led all the way and only Collins committed an error.

Things had quieted down by the time we got back to Chicago for the eighth game. The Series now stood at 4-3 in favor of the Reds and a lot of the skeptics decided that maybe the Sox meant business after all. It was Gleason's feeling that if Williams could finally win in the eighth game, then he would start Kerr in the ninth and have Cicotte ready for relief at the first sign of trouble. But Williams lasted less than an inning. Cincy drove him out with four runs, and that was the game and Series. We lost 10-5 as Eller pitched his second win for Cincinnati.

If there is any doubt about our trying to win the Series, let's look at the record. Jackson was the leading hitter with .375. He didn't commit an error. Weaver was our second man with .324. He didn't boot any, either. Total hits favored Cincy only 64 to 59, and each side committed 12 errors. Though I hit only .233, it was still seven points better than our star Eddie Collins, and two of my hits knocked in winning runs.

Our losing to Cincinnati was an upset all right, but no more than Cleveland's losing to the New York Giants by four straight in 1954. Mind you, I offer no defense for the thing we conspired to do. It was inexcusable. But I maintain that our actual losing of the Series was pure baseball fortune.

The loser's share amounted to $3,254 apiece, which Comiskey held up while he conducted a private investigation. I never did get any part of Rothstein's $10,000 and I don't know who did. Since Rothstein probably won his bets anyway, he never gave us any trouble. Naturally, I would have liked to have had my share of that ten grand, but with all the excitement at the Series' end and with Comiskey's investigation, I was frankly frightened stiff. Besides, I had the crazy notion that my not touching any of that money would exonerate me from my guilt in the conspiracy. I give you my solemn word I don't know to this day what happened to the cash.

Strong Minds and Weak Backs

Nice Guys Finish Last, Leo Durocher with Ed Linn (1975)

19-year-old Leo Durocher joined the Yankees for spring training in 1925. I had been with the Yankees for only a couple of days when Miller Huggins, the manager, tested me. The way it has always been in baseball, the humpty-dumpties, the substitutes, come out early to take their batting and fielding practice, and then the bell rings and the hitting cage belongs to the regulars.

When the bell rung, I had already been working out for about thirty minutes fielding ground balls that were being hit to me by Wally Pipp, who had lost his job to Lou Gehrig during the season and was helping out where he could. Wally was great when it came to that kind of thing because he could hit ground balls a mile a minute, and nothing pleased him more than to drive one through you. After another ten minutes or so, I came into the bench for a drink of water, and Miller Huggins said to me, "Go on up and hit." I grabbed a bat from in front of the dugout, went into the batting cage, and, boy, did I get a blast. Ruth and Gehrig and the rest of them all started to scream, "Get out of here, you busher! Get out to the field where you belong!" Let me tell you, I just dropped the bat and got out of there and ran back for my glove. Miller Huggins said, "I thought I told you to hit." I said, "Well, they wouldn't let me." Very firmly, he said, "I told you to get up there and hit!" OK! I grabbed a bat and I strode to the cage holding the bat in one hand like a club. Nobody was going to run me out of there the second time. Nobody. As luck would have it, Babe Ruth was waiting to hit next. I jumped in from the right side and Ruth moved in the left side. "Get out of here, you humpty-dumpty," he roared. "Get lost!" I said, "You better talk to the Man over there because he told me to hit next and I'm hitting." And all around the cage, the regulars were hollering, "Get out, you busher. ... Break your bat over his head, Babe. ... Knock the cage down on him." Well, he was going to have to do something like that to get me out of there. I just stood my ground and yelled to the pitcher. "You're gonna have to pitch to both of us because I'm not getting out of here." With that, Mr. Huggins called in, "Let him hit, Babe. Get out of there."    L-R: Leo Durocher, Miller Huggins and Babe Ruth, Wally Pipp Babe growled and snorted and let me know I was "fresh as paint" but later, in the locker room, Mr. Huggins patted me on the back. He had a way of sitting next to me and talking very softly, as if it were in it together. As it was us against them. "Never lose that self-assurance that you're the best," Mr. Huggins would tell me again and again. "There are a lot of fellows around here with strong backs and weak minds," he would say. "You have a strong mind and a weak back. Let them do all the hitting, you use your head. And as long as you live, there will be a place for you in baseball. You'll be here when they're all gone."

I was Miller Huggins' boy from the first. My father and Rabbit Maranville, the other two important men in my life up to then, had both been small men. Miller Huggins was an itty-bitty man, no bigger than a jockey. He couldn't have stood more than five feet three, and he weighed maybe 120 pounds. Tiny as he was, he had been a big-league second baseman for twelve years, and from what everybody told me, one of the very best. He had managed the St. Louis Cardinals for three years, and the Yankees for eight. With the Yankees he had won three straight pennants, had suffered the humiliation of being hung out of a speeding train by Babe Ruth when the Babe was in his cups, and had fined the babe an unheard of $5,000 and made it stick by surviving Babe's "me or him" ultimatum. He loved me like a father, and I loved him like a son. I couldn't hit worth a damn - Babe Ruth nicknamed me "the All-American Out" - but Mr. Huggins kept telling me I'd stick around for a long time if I kept my cockiness and my scrappiness and that fierce desire to do anything to win. "Little guys like us can win games," he would say. "We can beat 'em," he would say, tapping his head just like Rabbit Maranville, "up here." Is Ruth's HR Total Fair or Foul?

Rich Marazzi, Baseball Digest (July-August 2020)

"Dad, I Don't Think I Can Play Ball"

The New York Yankees of the 1950s: Mantle, Stengel, Berra, and a Decade of Dominance,

David Fischer (2019) Mickey Mantle was in his rookie year of 1951 with the Yankees.

An eight-game winning streak propelled the Yankees into first place in early May. Leading the way was Mantle—raw, untutored, small town–shy, but obviously able to knock the ball a country mile. And he was able to do it from both sides of the plate. His father, Mutt Mantle, who thought of everything when it came to baseball, had started him on a program of switch-hitting at age five. By May 18, Mantle was hitting .316 with four homers (two right-handed and two left-handed), and led the AL with 26 RBIs. As a left-handed hitter, Mantle pulverized low pitches, golfing them prodigious distances. Right-handed, his best swing was a level one, generated a couple of inches below the shoulders. This swing produced line drives that outfielders simply couldn't get to in time.

As the season progressed, however, AL pitchers figured out Mantle's primary weakness and began to feed him a steady diet of high fastballs. As it happened, his production waned. He batted .175 without a homer over his final 11 games of May. After fanning in all five at-bats during a May 30 doubleheader in Boston, and being pulled before each game ended, he broke down in tears on the bench. Mantle's rookie season must have been nerve-racking for a rural kid. He was still only two years out of high school; he and his teenage wife, Merlyn, his high school sweetheart in Commerce, Oklahoma, were overwhelmed by the towering skyscrapers and the fast pace of the big city. On top of that, reporters from a dozen newspapers came into the locker room day after day with variations on the same question about his medical deferment from the Army due to a bone infection in his left ankle called osteomyelitis, the result of a high school football injury, that left Mantle open to criticism that he was shirking his patriotic duty.

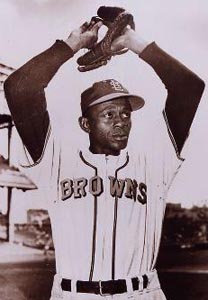

L-R: Rookie Mickey Mantle, Mutt Mantle, Satchel Paige His father's illness added to his troubles. Mutt Mantle had been diagnosed with Hodgkin's disease, a form of cancer. The prognosis was poor. Mutt could no longer sleep in a bed; he had to sit up and try to get some rest in a chair. The kid's eyes were red a good deal of the time, and it wasn't just from the frustration of watching his batting average drop under .260 by the end of June. The low point came on July 13 when Cleveland's Bob Lemon struck out Mantle three times. That prompted Stengel to farm out the youngster to Triple-A Kansas City for more seasoning. Mantle was devastated. He struggled in Kansas City, starting off hitless in his first 22 at-bats. Then he called his father in Oklahoma. "Dad, I don't think I can play ball," he said. Mutt Mantle drove all the way to the Kansas City hotel where Mickey was staying. Mickey expected a comforting pat on the back, but when Mutt walked into the room, he began packing his son's bag, saying that he was taking Mickey home. "Thought I raised a man," said Mutt. "You ain't nothing but a coward." Mantle asked his father for one more chance. Mutt relented, then he returned to the Oklahoma mines. "I'm gonna do it for him," Mantle told himself, and he followed through on his promise. The newly focused teenager rededicated himself to baseball and eventually rediscovered his powerful hitting stroke. Over his next 40 games with Kansas City, Mickey hit .361 with 11 homers and 50 RBIs. Mickey hoped it wouldn't be too long before the Yankees recalled him to New York. ...

Toward the end of the summer of 1951, the Yankees and the resurgent Cleveland Indians— winners of 13 games in a row to start the month of August—played leapfrog with each other in the standings as the White Sox and Red Sox faded badly. Rookie Gil McDougald was the team's leading hitter, and with DiMaggio not up to snuff, catcher Yogi Berra supplied most of the punch with Gene Woodling and Hank Bauer chipping in admirably. To fortify the offense, Mantle returned to fuel New York down the stretch. The kid returned to the Yankees on August 20, never to spend another moment in the minors. Now wearing the more familiar jersey number 7, Mantle batted .284 with six homers and 20 RBIs in the team's remaining 27-game charge. He hit a home run on August 29 off the ancient Satchel Paige, the famed Negro Leagues right-hander who was finishing up his legendary career with Bill Veeck's hapless St. Louis Browns.

"No One Was More of a Winner"

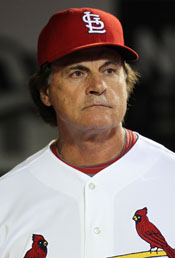

Stan McNeal, Cardinals Magazine, Issue 4 2020-21

Bob Gibson was one of the greatest athletes of the 20th century - the author of baseball's masterpiece seson by a pitcher, and landmark performance in a World Series. He also was intelligent, tough, humorous and a great motivator, say former Cardinals who knew him well.

Above all, they concur, Gibson was a winner. He wanted to win more than anything else - and had the talent to make it happen almost single-handedly. When Gibson retired in 1975, after 17 seasons spent solely as a Cardinal, his 251 wins were the most by a righthander in the National league during the live-ball era (post-1920).

Gibson was at his best when the stakes were highest and reeled off seven straight wins (two in Game 7s) across three World Series - each one a complete game - to establish a major league record that stands today.

Yet Gibson's best sport might not have been baseball. The same year he signed with the Cardinals (1957), he played four months for the Harlem Globetrotters after graduating from Creighton, the university in his hometown of Omaha, Neb. He attended on a basketball scholarship and also played baseball (.325 hitter), but his No. 45 was retired by the school only for hoops.

Bob Gibson in college Nevertheless, baseball would be the sport he dominated professionally. Nearly 46 years after his final pitch, Gibson remains No. 1 in nearly every meaningful statistic for Cardinals pitching, including wins, innings and strikeouts.

Along the way, he won two Cy Young Awards, an MVP and was named World Series MVP twice. He threw a no-hitter and was the first National league pitcher to surpass 3,000 strikeouts. He displayed his all-around athleticism by winning nine Gold Gloves and clubbing 26 home runs (including the postseason).

Given more run support, Gibson would have been a 300-game winner. He made 67 starts in which he gave up two earned runs or less, yet he was charged with the loss in 45 of those games and received no decision in 22 others.

Relying on a blistering fastball and biting slider, the 6-foot-1 righthander seemingly threw himself at hitters with a violent follow-through. He pitched with power, and purpose, and worked fast. He shunned chit-chatting with opponents, preferring to scowl at them instead (Gibson liked to claim he was squinting in order to see the catcher's sign). If a batter inched too close to the plate, he'd likely end up on his backside courtesy of a well-placed fastball. Gibson never led the league in hit batsmen, but he didn't mind hitters thinking he was coming after them.

"Intimidation is in the mind of the beholder," Gibson told fans during a Q&A event at Busch Stadium in 2014. "My idea was to win a ballgame, not to win an election. If you were intimidated by me, that was your problem, not mine. Most of the guys I hit was because I was throwing the ball inside and they were looking outside, so they would hit themselves and I would get credit for it."

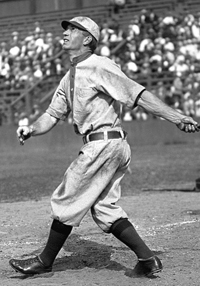

Bob Gibson pitches against the Boston Red Sox in the 1967 World Series. Gibson did more than talk tough - he was tough incarnate. Whatever he started, he expected to finish, and he ended up completing more than half the games he started. No other pitcher who has taken the mound since Gibson retired in 1975 has matched that feat (min. 250 starts). During a 13-season run (1962-74), Gibby failed to make 30 starts and pitch 200 innings only twice - and those two seasons might say even more about his grit.

The first, in 1967, came when Roberto Clemente's line drive broke his right leg on July 15. (Incredibly, Gibson stayed in that game and pitched to three batters after getting smoked!) As soon as the cast hardened, Gibson resumed throwing, and he was back on the mound in September to make five starts (3-1, 0.96 ERA), including the pennant-clincher. His legend went to another level in the World Series, when he started Games 1, 4, and 7, never trailed in a single inning, and posted three complete-game wins over the Red Sox to earn Series MVP for the second time in four years.

Six years later, at 37, Gibson tore cartilage in his right knee running the bases in a game at New York on Aug. 4. He initially tried to stay in the game, but the injury was bad enough that he wound up undergoing surgery with a projected recovery time of four to six weeks. But Gibson returned to start on Sept. 29, beating Steve Carlton and the Phillies to keep the club in a division race decided two days later.

The road Gibson navigated to the top of his profession presented hardships and challenges dating to his birth. The youngest of seven children, he grew up in a poor section of Omaha without a father, who died three months before Bob was born. As a child, he suffered from a litany of ailments, including rickets, hay fever, asthma, pneumonia, and rheumatic heart.

But a love of sports gained from his oldest brother, Josh, 15 years his senior, brought a different world to young Gibson. With Josh serving as father figure and coach, Gibson played his share of travel ball during summers and emerged as one of the area's top athletes in multiple sports at Omaha Tech High School. In the early 1950s, however, scholarships were difficult to come by for black student-athletes, and Gibson didn't know what he'd do after high school until Creighton came calling.

At this Catholic university, which had never given a black player a basketball scholarship before, Gibson's reputation as a fierce, unflinching competitor took root. He was tested early and often by his new teammates, said childhood friend Rodney Wead.

When he finished at Creighton, Gibson wasn't sure if he wanted to pursue a career in basketball or baseball, but he was all but ignored by the NBA, while the Cardinals offered him $4,000. Gibson reached the majors two years after signing, but his career didn't take off until 1962, his first full season after Johnny Keane took over as Cardinals skipper. Keane had been Gibson's first manager in the minors, and he assured the 26-year-old pitcher he'd be a regular part of his rotation. Gibson responded by earning his first of nine All Star Game selections and winning 15 games. By 1964, when he beat the Yankees twice in the World Series (capped by a Game 7 win on two days' rest), Gibson was in the discussion of baseball's biggest stars.

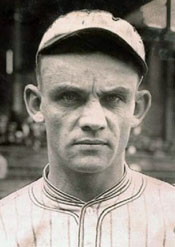

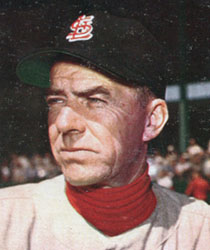

L-R: Johnny Keane; Gibson rejoices with Tim McCarver and Ken Boyer after last out of 1964 World Series. On the days he didn't start, teammates say Gibson put away his game face and was a clubhouse delight, quick to tease others but also willing to be the target of a joke.

"He was a guy rich in humor," said another close friend, former Cardinals catcher Tim McCarver. "When he pitched, he had his routine and all that went with it. But he was an easygoing guy. People don't believe that, but I don't care. He was."

In 1971, Satchel Paige Came to Cooperstown

Scott Pitoniak, baseballhall.org

Leroy "Satchel" Paige had preached often about not looking back "because something might be gaining on you." But as the legendary pitcher, showman and civil rights activist approached the podium on the Library steps outside the Baseball Hall of Fame the morning of Aug. 9, 1971, he had no choice but to violate one of his most popular commandments.

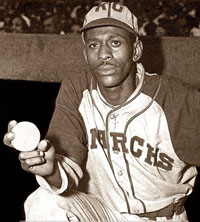

For seven minutes, the Hall’s first Negro Leagues inductee would look back, with humor and poignancy, on a four-decade baseball odyssey that had seen him barnstorm to every nook and cranny of the United States – and beyond. That Paige had finally arrived at a destination he never thought would open its doors to him totally blew his mind. The man who had struck out Jim Crow and laid the foundation for Jackie Robinson to integrate a sport and a nation soaked in the applause of the 2,500 mostly white spectators who had congregated in Cooperstown that historic day. But, while basking in the limelight, the tall, slender 65-year-old couldn’t help but feel conflicted. Voices dueled inside Paige’s head. "Should he be grateful that the lords of hardball were finally acknowledging that blackball had brilliant players, or should he resent them – and all of America – for making him pitch his best ball in the shadows?" author Larry Tye explained in his award-winning biography, Satchel: The Life and Times of an American Legend. "Was what counted that he was the first vintage Negro Leaguer to be voted into this most exclusive club and the (first) pitcher ever to make it with a losing record in the (white) Majors? Or was it that the Hall had tried to banish him to a separate and unequal wing?" Though Paige had every right to be bitter, he opted to express gratitude rather than regret when he arrived at the podium and was shown the bronze plaque that would hang near ones immortalizing Babe Ruth, Walter Johnson, Bob Feller, Dizzy Dean and Robinson.     L-R: Satchel Paige with Kansas City Monarchs, Cleveland Indians, St. Louis Browns, and KC Athletics On Feb. 9, 1971, Paige had been nominated to the Hall of Fame, beginning a process that would end with his induction. "Since I’ve been here, I’ve heard myself called some very nice names,’’ he began, grinning broadly beneath horn-rimmed glasses. "And I can remember when some of the men (enshrined in the Hall) called me some bad, bad names when I used to pitch against them."

Paige evoked more laughter when he talked about how former Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck had been lambasted for signing him to a contract in 1948 at the advanced age of 42. "They told him to get anyone but Paige – he’s too old,’’’ Satchel said, pointing to his former boss in the crowd. "Well, Mr. Veeck, I got you off the hook today." Paige mentioned how he once pitched 165 straight days in a row, and jokingly explained why he took his sweet time walking to the mound. "I never rushed myself,’’ he deadpanned, "because I knew they couldn’t start the game until I got out there." His speech was interrupted by laughter 13 times, but it was much more than a comedic monologue. There were touching moments, too, like when he spoke candidly about how he wished he – not Robinson – had been the one to break baseball’s color barrier. But he added that, upon further reflection, he realized Jackie had been the right man for that enormous challenge. Paige concluded by saying he "was the proudest man on the earth today," prompting a standing ovation. Ted Page, a former teammate, was among those springing to their feet. "I cried a little, but I came away from that ceremony a lot taller,’’ Page told the New Pittsburgh Courier, a newspaper with a predominantly Black readership. "When Satch stood up to be inducted, he was standing up for all of us who had played the game during the days when we knew we were good but weren’t recognized for being that way. His acceptance was vindication that we were as good as any man. I’m only happy that I was alive to see it." Paige’s unrivaled pitching and showmanship, particularly in interracial exhibition games against white aces like Dizzy Dean and Bob Feller, had paved the way for baseball integration. His induction into the Hall a half century ago would blaze trails, too. It opened the shrine’s doors for Josh Gibson, Oscar Charleston, Cool Papa Bell, and other Negro League legends whom history had forgotten. In the 10 years following Paige’s immortal moment, nine more of his Black contemporaries were enshrined. In 2006, a special committee righted a bunch more wrongs, electing 17 Black baseball pioneers, including the first female inductee, former Negro Leagues owner Effa Manley. In total, 34 Negro Leagues legends have followed Paige to Cooperstown. Writers from African-American newspapers had long lobbied for Paige’s inclusion, but the campaign among the mainstream, white media didn’t really start until 1952 when Sport magazine’s Ed Fitzgerald publicly championed the cause. It would be another decade before the movement gained steam. According to Donald Spivey’s biography, If You Were Only White, a "Paige For Hall of Fame Committee" was formed in Connecticut in 1961, with founder John Henry Norton collecting letters of support. Not surprisingly, Veeck became an ardent supporter, telling reporters: "If Paige had been brought up to the majors in his prime, today’s Cy Young Award would be known as the Satchel Paige Award." Feller, who had waged mound duels with Paige in front of overflowing crowds, also jumped on board, calling Satchel’s exclusion from the Hall "patently unfair." The greatest impetus, though, would come from Ted Williams during his 1966 Hall of Fame induction speech. His unexpected comments pushing for the enshrinement of Paige, Gibson and other Negro Leaguers prompted organized baseball to take action. Two years later, a special 10-man committee was formed to recommend which Black pioneers should be inducted. That Paige would be the unanimous first choice was not surprising, given his crossover popularity and achievements. In addition to his barnstorming tours, he had helped Cleveland win a pennant and World Series title, and was the first African-American pitcher to start a game in the white big leagues and pitch in a Fall Classic. By tossing three scoreless innings in a 1965 game for the Kansas City Athletics at age 59, Paige made good on another one of his adages: "Age is a matter of mind over matter. If you don’t mind, it don’t matter." His pithy sayings and humorous names for his array of pitches ("Bat Dodger," "Bee Ball," "Hesitation Ball") contributed to the larger-than-life persona he had created, but the slapstick occasionally muddied the argument that he was the greatest pitcher of all-time. Though records are sketchy, the best information available suggests Paige had an overall Negro Leagues record of 146-64 with 1,620 strikeouts and just 316 bases on balls, and a American League record of 28-31, with a 3.29 earned run average and 33 saves. Paige argued those stats significantly short-changed him. He claimed he pitched in more than 2,500 games, winning roughly 2,000 of them, with 55 no-hitters and somewhere between 250-330 shutouts. Numerous Hall of Famers vouched for his greatness. Dean said his fastball looked like a change-up compared "to that little pistol bullet Satchel shoots up to the plate." Joe DiMaggio said Paige was the best and fastest pitcher he faced. Slugger Hack Wilson claimed Satchel made baseballs look as small as marbles to batters struggling to see and hit them. The announcement of Paige’s unanimous election at a packed press conference in Manhattan on Feb. 9, 1971 was supposed to be a crowning moment for him and for baseball. But the festivities took a sour turn when it was revealed his plaque would hang in a different room than previous inductees. Though Paige publicly accepted this "separate but unequal" decision – "I’m proud to be wherever they put me" – the media did not. "The notion of Jim Crow in Baseball’s Heaven is appalling,’’ columnist Jim Murray wrote in the Los Angeles Times. "What is this – 1840? Either let him in the front of the Hall – or move the damn thing to Mississippi." Jackie Robinson suggested Paige boycott the induction. Privately, Satchel seethed, telling friends, "The only change is that baseball has turned Paige from a second-class citizen to a second-class immortal." On July 7 – Satch’s 65th birthday – saner heads prevailed and MLB Commissioner Bowie Kuhn and Hall President Paul Kerr announced Paige’s plaque would hang in the main hall. "I guess they finally found out I was really worthy,’’ Paige told reporters. "I appreciate it to the highest." Following his induction, he spoke frankly with reporters on a variety of topics, including his candidacy to become MLB’s first Black manager. "I could manage easy – I’ve been in baseball 40 years,’’ he said. "And I would want to manage." But he also offered a reason why it wouldn’t happen. "I don’t think the white is ready to listen to the colored yet,’’ he said. "That’s why they’re afraid to get a Black manager. They’re afraid everybody won’t take orders from him. You know there are plenty of qualified guys around." Among them was Frank Robinson, who would topple that racial barrier four years later when he was hired to manage the Indians. Paige’s comments had set the wheels in motion. It was all part of his remarkable, trailblazing journey – a journey that saw him bust open some doors in Cooperstown 50 summers ago, clearing a path for Black pioneers to finally feel at home in the home of baseball. The More, the Merrier

Tom Verducci, Sports Illustrated, October 2020

In 1995, the playoffs gave us a thrilling series that changed the fortunes of two teams, helped the game heal, and made a convincing argument for a bigger postseason field. Few baseballs in motion held more suspense than the one 25 years ago that skipped across the AstroTurf of Seattle's Kingdome like a rock over a pond. The skipping lasted long enough to allow the calculus of history to play out in your head.

Could the runner on first dash home faster than the baseball could be returned there? Was Seattle about to lose its Mariners? Were the Yankees about to lose their manager? Would this first nationally televised playoff game in two years bring back fans who had deserted MLB because of a players strike? Would people care about postseason baseball now that - gulp! - second-place teams were invited? This year (2020) the bar for postseason entry was lowered again. Eight of the 15 teams in each league qualified, opening the door for the possibility of a sub-.500 entrant. ... Structure and settings may change, but as the Mariners and Yankees proved in an epic 1995 American League Division Series, once the ball is put in play, the game has a way of writing its own unforgettable, unscripted narrative. The left field wall interrupted the baseball's bouncing, redirecting it into the glove of outfielder Gerald Williams. He whirled and threw it on one bounce to the relay man, SS Tony Fernandez, who spun and fired a strike into the mitt of C Jim Leyritz just as the runner, Ken Griffey Jr., threw himself toward home plate with a feet-first slide. ... Griffey beat the ball to the plate. The two-run, 11th-inning double by Edgar Martinez in Game 5 of the ALDS is the only time a series ended on an extra-inning hit that turned a deficit into a victory. The winning run, winning hit and winning decision (Randy Johnson) all belonged to Hall of Famers. The final score was 6-5. "The best game. The best series ever played," Seattle reliever Norm Charlton said in the clubhouse. "You saw two teams leave the field exhausted because neither one of us had a damn thing left." Like a deus ex machina, Johnson came out of the bullpen on one day of rest to pitch a third elimination game in seven days. His back gave out the next year. New York starter David Cone threw 147 pitches before he trudged off the mound, visibly exhausted. So withered was Cone he would stay in his New York City apartment for the next week with the shades drawn and a right arm so achy he could not comb his hair. Six months later he suffered a career-threatening aneurysm in that arm.   Jack McDowell pitches to Edgar Martinez. Cone had served as a prominent union leader during the 1994-95 strike, after which attendance cratered 20%. Said Cone after the game, "If this doesn't do a lot to diminish the image of the greedy ballplayer, I don't know what will."

The series provided the best argument for the newly expanded playoffs, which the strike had wiped out in 1994 and purists had derided. Second-place New York needed a 25-6 finish to grab the first-ever AL wild card, breaking a 13-year playoff drought, the franchise's longest since it was known as the Yankees. Seattle mounted the third-greatest comeback in history (13 games out of Aug. 2) to seize its first playoff spot. Alas, during that run a stadium-funding referendum failed by about 1,000 votes out of a half-million cast. The Mariners seemed bound for St. Petersburg. Every game in the series was epic, even if most people didn't get to see them because coverage was regional. That meant 80% of the country missed the Yankees' 15-inning win in Game 2 that gave them a 2-0 lead. "I remember leaving Yankee Stadium and wondering how we were going to win a game there," New York manager Buck Showalter says of the Kingdome. "It was all the bounces and the noise. It was like playing in a pinball machine. All of our communication had to be done in the runway behind the dugout." The Yankees were in front in every game and lost the series. They blew eight leads, including a 5-4 advantage against Johnson in the 11th in Game 5. "I was out there in right field in that last inning," Seattle's Jay Buhner said after the game, "thinking, My God, this is the best game I've ever seen." It would only get more exciting. A bunt single by Joey Cora and a single by Griffey set the stage for Martinez against Jack McDowell, whom Showalter picked to make his first career relief appearance over closer John Wetteland. McDowell hung an 0-and-1 splitter. Martinez smacked it on a line, sending the baseball and history into motion.  Ken Griffey Jr. scores the winning run as C Jim Leyritz reaches for the ball. Another vote in Seattle took place in October. This one passed, keeping the Mariners in town. Only by the grace of the three other division series having ended did Game 5 get the coverage it deserved. It was the first nationally televised postseason game since Joe Carter homered for the Blue Jays to win the 1993 World Series. It drew an overnight rating of 13.4, better than any of the past 12 World Series games. "This series," Showalter says, "was one of the first times people began to put '94 behind them. Ninety-four broke a lot of hearts. To this day I've had more people tell me this series was when they came back, when they said, 'O.K., this is why we love baseball so much.'" All Smoke, No Mirrors

Thomas Raber, Cardinals Magazine 2000 Issue 5 reprinted in 2020 Issue 2

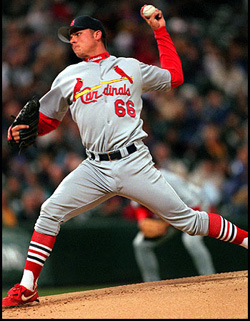

The 2000 Cardinals were holding onto something they hadn't had in more than a decade: a commanding lead atop their division. Thank GM Walt Jocketty for his savvy shopping over the previous offseason. Darryl Kile, Andy Benes and Pat Hentgen had been added to the starting rotation, and they provided a sturdy backbone for a team that spent only three days out of first place all year and built a 9 1/2-game lead by July 1. But if you were heading to Busch that summer, the pitcher you might have wanted to see take the mound for the first-place Cards was another relative newcomer - a rookie lefthander who lit up the ballpark with an electrifying presence and seemingly unlimited potential: Rick Ankiel.

Rick Ankiel's eyes fizz like two glasses of cola when he is either amused or challenged. You've seen the look as he glares in for the catcher's sign, his brown eyes peering over his black glove as if he's hiding a hand of poker cards. Just now, the eyes flash because he has been asked a silly question. "How are you feeling today?"

Trite to be sure, but maybe it's natural to wonder how a 21-year-old with a seemingly golden left shoulder might feel on a Friday afternoon in late June, when the sun is shining, he is not scheduled to pitch, and his high school buddies from just three years ago might be hitting the beach at his home in Port St. Lucie FL.

Just three days earlier, Ankiel had defeated the San Francisco Giants 7-2 at Busch Stadium, striking out eight batters in six innings. In two days, he would match serves with dominant Los Angeles Dodgers ace Kevin Brown for seven innings before a capacity crowd at Busch, leaving the game tied, 1-1, in an eventual 2-1 Cardinals victory.

Whether he's engaged in killer pingpong matches with the clubhouse attendants before game time, or wagging a big bat defiantly from the knob as he takes his stance during batting practice, Ankiel spreads the sense that he'd really like to be playing every day, somewhere in the lineup (he played the outfield in high school and for the USA Junior National Team when not pitching). His spirit for competition and his level of energy never are a problem.

"He impressed me from the get-go," says Cardinals manager Tony La Russa. "In every phase of things. He's got a good heart and a great gut. Courage. And he's sure not afraid of tough situations."

To wit, Ankiel made it look easy on June 20 against the Giants. In the first inning he fanned San Francisco slugger Barry Bonds to help himself out of a jam. Ankiel later whiffed Bonds a second time. And still later he K'd Bonds again to make it a clean trifecta. Confidence comes easily to the man who turned 21 on July 19.

"He has talent," says pitching coach Dave Duncan, skipping fancy analysis.

"You know? Some guys come along and they can try as hard as they want to, and they never really develop the talent of being able to execute quality pitches consistently. But he has great physical ability. He's a very good athlete. He's a very coordinated athlete. He's got a real live arm. Great movement on the ball and good velocity.

"What he does that might be different from somebody else is still in the developing stages. Whether he's going to develop great command of his curveball or his changeup and be able to execute pitchers all over the strike zone, as he wants to, that's still in the future. But given time to learn how to do these things, I feel assured that he's going to be able to do them."

L-R: Rick Ankiel, Tony La Russa, Dave Duncan, Mike Easler After being the 72nd selection in the June 1997 amateur draft - straight from Port St. Lucie (FL) High - Ankiel played his professional season in '98 at Class-A Peoria and Prince William, recording a combined 12-6 record, a 2.42 ERA, and 222 strikeouts in 161 innings. In '99, he advanced to Class-AA Arkansas and Class-AAA Memphis, progressing so rapidly that he found himself with the Cardinals by August of '99. In nine games and five starts with the big club, he went 0-1 with a 3.27 ERA, and he struck out 39 batters in 33 innings.

Some say Ankiel will step up to notch the National league Rookie of the Year honor this year. At the halfway point of the season, he led all major league rookies in every significant pitching category, including ERA (3.44), wins (6), winning % (.667), innings (86.1), strikeouts (86) and opponents' batting average (.228). But he's still learning to pitch and, to his credit, he knows that he is.

On the mound, Ankiel is Exhibit A of composure and style. You've seen the fluid, no-windup delivery, and the way he tucks his glove neatly at the waist when he throws. His follow-through brings his left leg high behind him, like the tail propeller of a helicopter.

What he really likes is taking his turn at bat. Through the first half of the season, he had smacked two HRs, driven in six runs, and was batting a notable .278 - nifty for a pitcher. He had been called off the bench three times between starts to pinch-hit. In fact, he claims to enjoy batting as much as shutting opposing batters down.

"Yeah. Hitting is a fun part of the game," he says. "There's nothing like it. You can go up there and be a hero with one swing. I don't think there's any better feeling than hitting one out or getting a base hit. Just getting a chance to compete."

Cardinals hitting coach Mike Easler is impish, but respectful, when discussing the subject of Ankiel at the bat. The pitcher may not be the next coming of Babe Ruth, but he is willing to work and to listen about the art of hitting.

"Ricky's a competitive person," Easler says. "He's the type of guy who was probably a great hitter in high school. When he gets tohome plate he grits and grinds just like he does on the mound. He has that, 'I'm not going to get beat' attitude, and that's the greatest thing you can see in a young, talented and strong kid like him. He asks questions, which is good. He's going to win a lot of games for himself over his, hopefully, 15- or 20-year career."

Born at Fort Pierce FL, Ankiel grew up admiring the likes of Dwight Gooden, Darryl Strawberry and Mark McGwire. Baseball was the only sport he played, perhaps an indication of his single-minded drive.

"Here's the biggest thing I can say about him," Cardinals C Mike Matheny begins. "He'll go out and have, not a shaky outing but an outing that he doesn't think was good for him. And the adjustments he makes within five days to get on the mound again and come out and really throw the ball well - that's something you can't teach a young guy to do. Usually they take their lumps, and they come in bunches, and it can set them back. But he's just got so much drive, he's pushed himself harder than anybody could push him. That, along with all the talent he has, is really going to set him apart. It's amazing, given how old he is, and with all that's been going on in his life."

In the clubhouse after the June 25 Dodgers game, Ankiel is entertaining a cluster of reporters.

In some ways, Ankiel comes off as a veteran.

"Our young man stepped up and matched their man (Kevin Brown) today," La Russa says. "When you face the good ones, you get better yourself."

In other ways, he seems like a kid.

"I got a hit today," Ankiel chirps. "I'm pumped up about that. That's going to keep me on Cloud 9 probably for a couple of days now."

So, when will Ankiel feel he has it made? With so much before him, will he have to achieve a specific goal, or will he just know it when he feels it? Or maybe he feels he has arrived right now.

"I don't know," Ankiel says. "We're all here playing the same game, so it doesn't really matter what level of maturity or skill you are at, I don't think. The results are what count. It doesn't matter what level you think you're at when you're on the field. You go out and give your best and hope for the best when it happens.

He is feeling amused and challenged. And his eyes are fizzing like cola.

Postscript: Rick Ankiel's story is one of the saddest in Cardinals history. He finished the 2000 season 11-7 with a 3.50 ERA. Because of injuries to several starting pitchers, La Russa chose Ankiel to start Game One of the NL Division Series against the Braves. Rick pitched two scoreless innings before coming unhinged in the third inning. He allowed four runs on two hits and four walks and threw five wild pitches before being removed with two outs. In his next start in Game Two of the NL Championship Series against the Mets, he threw only 20 pitches, five of which got past C Eli Marrero. Rick was unable to regain his touch in 2001 and was sent down to AAA. In 4 1/3 innings, he walked 17 batters and threw 12 wild pitches. An elbow injury that required surgery compounded his problems. Eventually, he moved to the outfield and made the league All-Star for AAA Memphis in 2007. He returned to the Cardinals in 2008 as an outfielder and played for five other teams through 2013 when he finally retired.

There's No Sleeping in Baseball

Rich Marazzi, Baseball Digest, March/April 2021

It's rare that a player is tossed in the middle of a play, but it occurred on September 17 this past season at Chicago's Guaranteed Rate Field, where the White Sox hosted the Minnesota Twins. Josh Donaldson led off the top of the sixth inning with the score tied 2-2. He had a 2-0 count facing Sox right-hander Reynaldo Lopez. The next pitch appeared to be off the plate, but umpire Dan Bellino called it a strike. Donaldson, who had an exchange with Bellino earlier in the game, had words again with the umpire. On the next pitch, Donaldson homered down the left-field line. After rounding the bases, he kicked dirt at home plate as he crossed it in protest of Bellino's called strike. Bellino booted him immediately and Donaldson, apparently thinking he had missed the plate, returned to touch the dish and then argued as he kicked more dirt on it.

Assuming Donaldson failed to touch the plate, was he permitted to go back and touch it after the ejection? The answer is yes. Rule 8.01 (d) states: "If an umpire disqualifies a player while a play is in progress, the disqualification shall not take effect until no further action is possible in that play."

Boston Red Sox C Sammy White pulled a rock in a game against the Detroit Tigers on August 28, 1956, at Fenway Park. In the top of the sixth, Tigers C Red Wilson was facing Mel Parnell with Bill Tuttle on second and two outs. Wilson hit a ball up the middle that was fielded by Milt Bolling behind second base. Tuttle tried to score on the play and Bolling fired home to head off the Tigers runner. Tuttle was called safe by umpire Frank Umont, which caused White to go into a frenzy. He disgustedly heaved the ball into the outfield and was immediately tossed by Umont. Meanwhile, Wilson continued to circle the bases and score. Wilson was credited with a single and White was given an error and a ticket to the clubhouse.

If a player gets the thumb after the game ends, he is fined but not disqualified for the next game. On June 23, 2010, the Los Angeles Angels defeated the Los Angeles Dodgers, 2-1, in Anaheim when the Dodgers' Russell Martin was called out at second base to end the game. Martin fumed over the call and was expelled. Two nights later, Dodgers 1B James Loney was disqualified following the game when he argued a Mariano Rivera third-strike call by plate umpire Phil Cuzzi in the Dodgers' 2-1 loss to the New York Yankees.

L-R: Josh Donaldson, Sammy White, Russell Martin Some of the most intriguing ejections have occurred in minor-league games. In a May 24, 1988, Texas League contest in El Paso, umpire Brian Owen chased Paul Streizin, the Diablos' public address announcer, for playing a tape of singer Linda Ronstadt's "When Will I Be Loved?" which starts, "I've been cheted, been mistreated." Owen warned Streizen not to play the song after a controversial call in the fifth inning went against the Diablos in their game against the Jackson Mets. When Streizin repeated the tune at the end of the inning, Owen relieved the subborn PA announcer of his duties.

Three days later in Omaha, umpire Tony Manners removed organist Lambert Bartak from Rosenblatt Stadium for playing the theme song from The Mickey Mouse Club after a disputed call in a Triple-A game between the Tidewater Tides and Omaha Royals. "He was playing music derogatory to the profession," said Manners. The following night some 25 Omaha fans appeared at the park wearing Mickey Mouse ears. One was in a full Mickey Mouse costume.

Ever hear of a bat boy making an early exit? It happened on June 27, 1980, in an International League contest between the Charleston Charlies and Pawtucket Red Sox, when Sox bat boy Billy Broadbent was expelled by umpire Zach Rebackoff. "Rebackoff was not very well liked," recalled Broadbent. "One night he was giving me a hard time about not being quick enough in bringing him the baseballs. A few of the Pawtucket players heard him and told me that I didn't have to take that from him and the next time he gives me a had time, tell him to (bleep) off." Several days later Rebackoff was behind the plate and to expedite the delivery of the baseballs, he wanted Broadbent to stand behind the catcher when the pitcher was warming up. "I refused because I had gotten hit by a pitch once before during the season," explained the former bat boy, who currently serves the Red Sox as their video coordinator. "Twice he ordered me to stand behind the catcher, and I finally told him where he can go. He then calmly walked over to me, took the baseballs and said, "You aren't working any more tonight. You're outta here!"

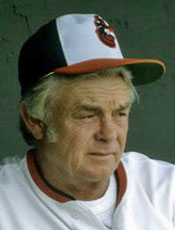

Baltimore Orioles manager Earl Weaver, who racked up 96 managerial ejections. Perhaps the most unusual one took place in the middle of the playing of the national anthem before the start of the game. Former umpire Doug Ford tells this story. "One night I had a play at first base that went against Weaver. The next night we were standing at home plate during the national anthem, and Weaver said, 'What are you going to (bleep) up tonight, Ford?' I said, "Whatever it is, you're not going to be watching because as soon as this last note is done, you're done with it. And furthermore, if you cover up home plate, everybody is going to think you're nuts because they don't know that I ran you.' He argued a little bit and left."

L-R: Earl Weaver, Edd Roush, Heinie Gros I'll put this piece to bed with the following story. During the 1920 season, the Cincinnati Reds and New York Giants played at the Polo Grounds when Giants LF George Burns hit a shot down the 3B line for a double. Reds skipper Pat Moran argued with umpire Barry McCormick that the ball was foul. During the course of the extended argument, the Reds' Hall of Fame CF Edd Roush put his glove on the ground and took a nap. When the game resumed, Roush was fast asleep. McCormick got tired of waiting, and despite the efforts of Heinie Groh to wake his teammate, the ump ejected Roush for delay of game.

|