Clash of Titans

Games featuring a future Hall of Fame coach on each sideline.

October 31, 1903: Michigan @ Minnesota

Fielding Yost vs Henry Williams

Where's Our Little Brown Jug?

Fielding Yost already had a national reputation when he became head coach at Michigan in 1901 at age 30. His first team, Ohio Wesleyan, tied Michigan and beat Ohio State on their way to winning the state championship. He coached Nebraska and then Kansas to Missouri Valley titles in 1898 and 1899. Keeping up his parapatetic pattern, he moved to Stanford in 1900 and coached the Indians to a 7-2-1 record.

When Yost moved to Michigan in 1901, he immediately turned the Wolverines into a powerhouse. His first squad shut out all 11 opponents with the closest game being a 21-0 triumph at Ohio State. Using what today would be called a "hurry up no huddle" offense, the Wolverines were christened the "Point-a-Minute" team, a monicker that would be extended to his subsequent Michigan teams.

Michigan won all 11 games in 1902 also, but this time gave up six points each to Case and Minnesota. The tightest contest was the 6-0 victory over Wisconsin. Read about that game.

The star of both undefeated teams was HB Willie Heston. Years later, Yost said, "Heston never had an equal. He was the quickest runner who ever lived, he could hit the line with the best, and he had an unusual balance."

The winning streak reached 29 games when the Wolverines trounced their first seven opponents in 1903 with none of them scoring a point.

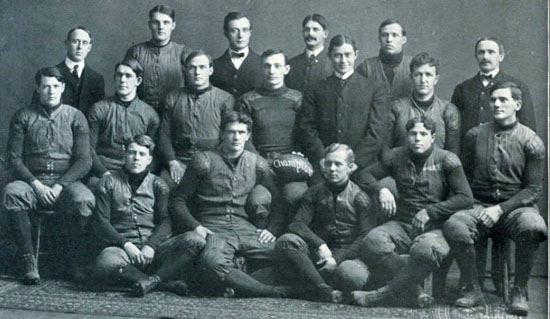

1903 Michigan football team

Fielding Yost in the second to last row. Willie Heston is second from the right in the first row.

(University of Michigan Michiganensian Yearbook Class of 1904)

Michigan's eighth opponent loomed as the biggest test since Yost became the coach. The Minnesota Golden Gophers of Coach Henry L. Williams were also a juggernaut. They too had shut out all seven college opponents with the closest contest being the 29-0 triumph over Carleton.

While playing halfback at Yale in 1889-90, Williams helped Coach Walter Camp invent the "tackle-back" formation wherein both tackles lined up off the line of scrimmage.

Williams began his coaching career at West Point in 1891 while teaching at nearby Siglar Academy. He guided the Cadets to a 4-1-1 record in their first full year of football competition.

Williams moved to Philadelphia to enroll in the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine while coaching at William Penn Charter School from 1892-99. During this period, Henry turned down an offer from his Yale teammate, Amos Alonzo Stagg, to be his assistant at the University of Chicago.

Williams became a gynecologist and served as a professor of gynecology for two years at Penn. He also spent parts of three years studying at medical centers in Berlin and Vienna.

Following Stagg's recommendation, Minnesota hired "Doc" Williams as its football coach in 1900 at a salary of $2,500 a year. The three-year contract allowed him to practice medicine. It was one of the best decisions the university ever made as he compiled a record of 141-34-12 over 22 seasons.

Decades later, Sigmund Harris, Williams' quarterback at Minnesota in 1902-04, summarized his coach's approach to football this way. "Williams never devoted the time to fundamentals, blocking, charging, and tackling, to anywhere near the extent (Bernie) Bierman, (Knute) Rockne, and some other coaches did. He was first and foremost a tactician, a deviser of offensive plays, equally expert at setting up a defense for any type of offense. I consider him to be the type of (Pop) Warner more than any other."

One of Williams' contributions to football strategy was the "Minnesota Shift." Offensive players suddenly switched to a new formation just before the ball was snapped in order to keep the defense off balance and disguise the point of attack. To show the attitude of the time, Williams offered his shift to his alma mater but was rebuffed because Yale would "not [take] football lessons from a Western university."

The difference between the Minnesota Shift and earlier versions was explained this way: "The old shift was what might be called a one-position shift, since the men moved from their regular station to another and then started with the snap of the ball. The Minnesota play may be called a two-position shift in that it requires the men in it to take two positions other than their regular stations before the ball is snapped. Hence the common term 'jump' shift, the men practically jumping from the first position into the second. Now while the old shift settled the nature of the line at once, the new shift keeps the nature of the line in doubt tothe defense until almost the instant of the snapping of the ball."

Williams' shift was legal because it wasn't until 1927 that the rules required shifting offensive players to be stationary for one-second before the snap.

Yost's Wolverines had defeated Williams' Gophers 23-6 at Ann Arbor in the final game of the 1902 season.

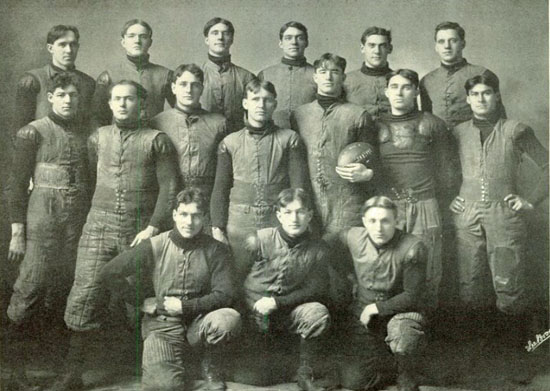

1903 Minnesota football team (University of Minnesota Gopher Yearbook Class of 1904)

Fearful that Minnesota fans would contaminate the drinking water for his sideline, Yost told his team manager Tommy Roberts to buy a large jug of water at a Minneapolis store. Roberts purchased a five-gallon Red Wing Pottery jug for 30 cents. That innocuous decision would create a tradition that exists to this day.

The game was the first one whose progress was transmitted over a distance. A Michigan student, Floyd Mattice, the Athletic Association, and the Bell Telephone Company collaborated to bring Wolverine fans in Ann Arbor a "live" account of the game.

In Minneapolis, Bell engineers erected a wooden tower 40' high at the 55-yard line (midfield on the 110-yd field at that time). Mattice climbed to the wooden booth at the top of the tower and donned a headset. When he spoke into the transmitter, he was answered by a professor speaking from University Hall on the UM campus in Ann Arbor.

The telephone company ran special phone lines to the University Hall Auditorium and to several other cities. 3,000 people paid 25 cents each to hear Mattice's description of the game. However, they didn't hear it directly. The Bell engineers placed 10 telephones on 10 tables backstage in University Hall. Ten students, who knew football and the opposing team, sat at the tables in numbered order.

Following the plays through binoculars, Mattice described the progress of the game. Back in Ann Arbor, the students listened on the telephones to Mattice's description and took turns every few minutes telling the crowd what each had heard. The course of the game was also charted on a large diagram of a football field on the auditorium stage. As play progressed, a marker charted the position of the ball.

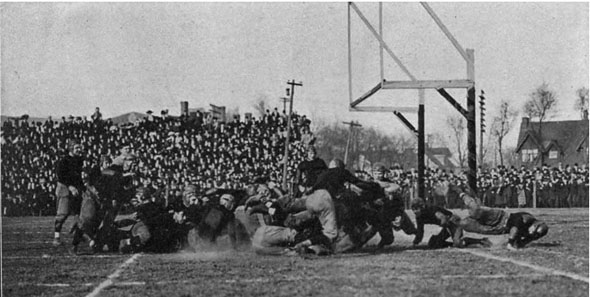

1903 Michigan-Minnesota action

Defenses Prevail

A crowd of 20,000, considered "the largest ever assembled at a game in the northwest," gathered under sunny 56° weather at Northrop Field in Minneapolis. The stands were full nearly an hour before the game, and standees were packed six deep outside the wire fence surrounding one end zone.

Strangely, the home team was late arriving on the field, delaying the opening kickoff by 14 minutes to 2:29 local time. Sunset would come just after 5 PM. The lost minutes would have a significant impact on the outcome.

Both teams seemed nervous at the start. QB Sig Harris, replacing injured first-string Minnesota QB Henry O'Brien, bobbled the opening kickoff and returned it only to the 15. Six plays later, the Gophers had to punt, but a bad snap from center forced Harris to run, and the Wolverines took over at the Minnesota 15.

The defenses dominated the 35-minute first half to the point whether neither side gained a first down (5y in three downs) until the ninth possession, when Michigan's Willie Heston and Joe Maddock gained 17y on consecutive runs. The Wolverines reached the Gopher 24 before bogging down.

Michigan soon had the ball back on Minnesota's 50 but fumbled, and the Gophers recovered. But penalties spoiled the chance and forced a punt. The scoreless half ended a few minutes later.

The Wolverines got close enough for Tom Hammond to attempt a place kick from Minnesota's 25. But the pass from center was bad, and the Gopher line swarmed Hammond before he could get the kick away at the 27.

Another Minnesota fumble a few minutes later gave the Wolverines the ball at the Gopher 45. Heston carried five straight times to advance the ball to the 25, but Willie's run on a third down fake punt failed to make the line to gain.

With the Gophers gaining consistently on punt exchanges, the home team drove inside the UM 35 on five of their remaining seven possessions of the first half. But three drives stalled on downs, one of them at the 14, and captain Ed Rogers missed a 45y field goal attempts on the fourth. Halftime stopped the final penetration. So despite being outplayed, the Wolverines went to the locker room in a scoreless tie. If the Gophers had doubted they could hang with Michigan, they were now inclined to believe their coach, who had been telling them for weeks they could defeat the Wolverines.

More Michigan-Minnesota action. The goal posts hang over the goal line.

Minnesota outgained Michigan in the first half 155y to 60. To jump start his offense, Yost told his team at halftime "to use trick plays and fake interference whenever possible."

The newspaper play-by-play accounts of the viciously played game repeatedly list "man hurt" or "man badly hurt." The crowd is reported as going "crazy" several times when a Michigan man is down, especially if it's Heston. At one point, the crowd yelled, "Put Yost off the field," when he objected to a holding call.

Gophers Batter Heston

Some Michigan fans heard Minnesota assistant coach Pudge Heffelfinger, a great lineman at Yale (1888-91), yelling from the sidelines, "Kill off Heston in the first ten minutes, or you'll lose." The crowd started chanting, "Kill off Heston." The umpire Minnesota selected, Henry Clark, received heavy criticism from Michigan fans for failing to penalize Minnesota's rough play.

By the second half, Heston looked like a boxer who had been in a 15-round heavyweight match. After the game, he bitterly denounced the Gophers for their rough play. "They not only slugged, but they used their spikes." Longtime Michigan trainer Keene Fitzpatrick called the game "the worst, from the point of foul play, that ever came under my observation. I saw Heston punched any number of times, and once I saw a Minnesota man jump on [QB Fred] Norcross after he had caught a punt and knock him out with a blow to the jaw."

Minnesota Get First Break

The Gophers got the first break in the second half when Fred Norcross fumbled a punt, and Minnesota recovered on the Wolverine 30. Earl Current broke loose for a 7y gain followed by an 8y run to put the ball on the 15. Three runs gained a first down on the eight. But the next play resulted in a fumble that Michigan recovered on the three to stave off the threat.

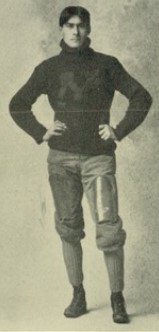

L-R: Henry L. Williams, Minnesota captain Edward Rogers, Willie Heston, Michigan captain Curtis Redden

(Rogers picture from University of Minnesota Gopher Yearbook Class of 1904)

(Redden picture from University of Michigan Michiganensian Yearbook Class of 1904)

The game devolved into a punting duel again with Michigan gradually working its way out of its territory on "fierce line plunges" until it pushed into Minnesota territory. Coming back after being "laid out" several times, Heston broke loose around left end for 15y to the 20. Play was stopped while injured men from both sides were treated with Dr. Williams caring for players on both teams.

Michigan Takes Lead

Michigan finally broke the scoring ice midway through the second half. From the Minnesota 40, Heston broke into the clear with only grass in front of him when S Harris made a game-saving tackle. On the next play, Heston started around left end only to be leveled by a hard tackle that made him woozy. But he stayed in and ran multiple times to put the ball on the five. Line bucks by HB Herb Graver and Hammond placed the ball just inches from the goal. QB Norcross called Heston's number again, but as he barked the signals, T Joe Maddock dropped back. "His face was cut and bleeding, too. One eye was a deep purple. 'Give me the damn ball!' he growled. 'Willie's done enough.' So Norcross handed to Maddock on what was called a "tackles-back" play, which, ironically, Coach Williams had co-invented with the immortal Walter Camp, his coach at Yale. Maddock smashed across the goal line for the first score of the game. Hammond booted the extra point to make it 6-0 Michigan with seven minutes left in the game. Maddock said after the game, "When I went over for the touchdown, I was punched in the back of the neck and kicked in the head at least 20 times."

Tom Hammond kicks the extra point to make it 6-0 Michigan. (Michigan Bentley Historical Library)

The touchdown silenced most of the crowd while in Ann Arbor, hundreds of people took to the streets to celebrate what certainly would be a Michigan victory.

With dusk setting in, Sig Harris elated the Minnesota fans by taking the kickoff and meandering through six UM defenders 45y to the 50. Suddenly, "Hope sprang anew in the breast of the Minnesota rooters," wrote the Minneapolis Journal. Captain Edward Rogers gained 10 around right end. Several more runs moved the pigskin to the 33 before the Michigan defense tossed the runner for a 10y loss. That forced a punt that Michigan caught on the five with four minutes to play.

Minnesota's hopes suffered a setback in the form of a 20y penalty for unnecessary roughness. Three plays later, Michigan punted to Harris, who ran it back 10y to Minnesota's 50.

Gophers Tie Score

In a move that seems incomprehensible today, the Gophers immediately punted back. But the strategy paid off because Graver fumbled the ball, and a Minnesota man pounced on it at the 20.

Egil Boeckman carried twice for a first down on the 15. Several more runs put the ball on the five. Fred Schacht scored from there. With the Minnesota fans collectively holding their breath, Rogers kicked the tying point. Michigan 6 Minnesota 6

Game Ends Early

The fans stormed the field, and the officials ended the game with two minutes left since it would be impossible to clear the field before darkness set in completely. That infuriated Yost because his team wasn't given a chance to regain the lead in the remaining time. It was the first time in his Michigan coaching career that he left a field without the victory.

In a way, a tie was a fitting way to end the contest because Minnesota dominated the Wolverines in almost every statistical category except points scored. The Gophers outgained the Wolverines 237-152. The only stat that favored Michigan was rushing yardage in the second half: 122-196.

Both coaches said their team should have won. "I think Minnesota should have won," said Williams, "but we are satisfied with the result." Yost: "We should have won. The boys played well, but luck was against them. Minnesota has a great team, and I wish we might play them again."

The headline in the Minneapolis Tribune the next day proclaimed: "Tie Game; Minnesota Wins."

Michigan Leaves Jug Behind

Because the chaos of the field and the rush to catch their train, the Michigan team and staff hurried off the field to the safety of the locker room, leaving their water jug at Northrup Field. (Manager Roberts claimed in 1956 that the jug had served its purpose. So he intentionally left it behind.)

When the Michigan team arrived back in Ann Arbor, a crowd of 5,000 met them at the depot, singing and yelling. The crowd attached ropes to a bus and towed the team to campus while continuing their songs and yells. At a rally on campus, Heston told the crowd that the Gophers were "the roughest lot of sluggers I ever went up against." Willie's right eye was nearly swollen shut, and his nose bore "marks of terrific smashes." Maddock added, "I don't know how many times I was hit and kicked, but I think I got at least 20 blows on the back of my neck."

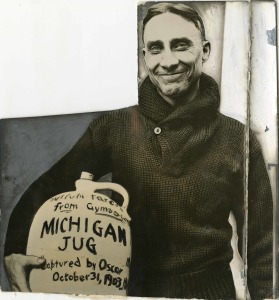

Sunday morning, a Minnesota custodian named Oscar Munson found the water jug while cleaning the visitors' locker room. He took it to Athletic Director "Doc" Cooke, who decided to keep the jug as a memento of the tie against Michigan. He had Munson inscribe on it in large print "Minnesota 6" and in small print "Michigan 6." They added, "Michigan Jug captured by Oscar October 31, 1903." Cooke had the jug suspended from the ceiling of his office so every visitor would see it.

The story gets murky from that point. One version says that Yost sent a letter asking for the jug to be returned, and Cooke wrote back, "We have your little brown jug. If you want it, you'll have to win it."

The game had been so brutal that the two schools would not agree to play each other again for another six years. Another version of the jug story says that Cooke and the captain of the 1909 Minnesota team decided that playing for the jug "might be material to build up a fine tradition between the two institutions." Yost and Michigan's captain agreed, and the "Little Brown Jug" has been the traveling trophy for the Michigan-Minnesota rivalry ever since.

L: Minnesota's head of athletics L. J. Cooke with the Michigan jug.

R: A replica of the jug on display at Michigan in recent years

References:

Football for Public and Player, Herbert Reed (1913)

The History of American Football: Its Great Teams, Players, and Coaches, Allison Danzig (1956)

Great College Football Coaches of the Twenties and Thirties, Tim Cohane (1973)

The Little Brown Jug: The Michigan-Minnesota Football Rivalry, Ken Magee, Jon M. Stevens, and Glenn "Shemy" Schembechler III (2014)

Miracle Moments in Michigan Wolverines Football History, Derek Kornacki and Steve Kornacki (2018)

Football for Public and Player, Herbert Reed (1913)

The History of American Football: Its Great Teams, Players, and Coaches, Allison Danzig (1956)

Great College Football Coaches of the Twenties and Thirties, Tim Cohane (1973)

The Little Brown Jug: The Michigan-Minnesota Football Rivalry, Ken Magee, Jon M. Stevens, and Glenn "Shemy" Schembechler III (2014)

Miracle Moments in Michigan Wolverines Football History, Derek Kornacki and Steve Kornacki (2018)