Clash of Titans

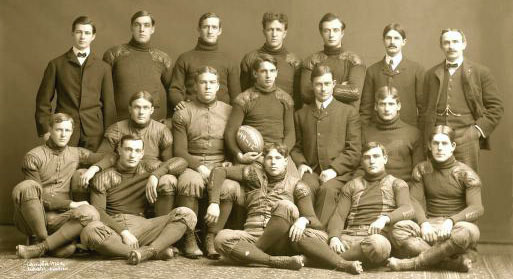

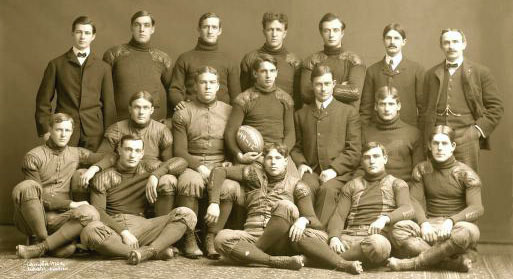

1902 Michigan Wolverines (University of Michigan Michiganensian Yearbook Class of 1903)

Coach Yost is just to the right of the player holding the football.

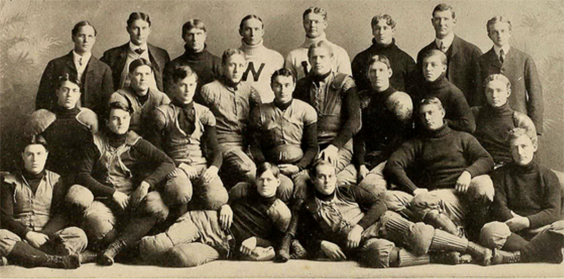

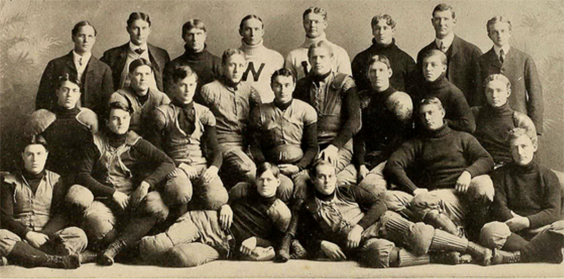

1902 Wisconsin Badgers (University of Wisconsin Madison Badger Yearbook Class of 1904)

Coach King is at the far left in the last row.

Marshall Field during a 1900 game

L-R: Harrison Weeks, Joe Maddock, Albert Herrstein

(Bentley Historical Library University of Michigan)

Michigan-Wisconsin action 1902 (tiptop25.com)

More Michigan-Wisconsin action (Michiganensian Yearbook Class of 1903)

.jpg)

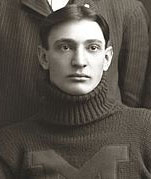

L-R: Everett Sweeley, James Lawrence, Curtis Redden

Games featuring a future Hall of Fame coach on each sideline.

November 1, 1902: Michigan vs Wisconsin

Fielding Yost vs Philip King

Fielding Yost, a West Virginia graduate, became Michigan's head coach in 1901 at age 30. He never came close to a losing season in his previous four seasons at Ohio Wesleyan, Nebraska, Kansas, and Stanford, compiling a record of 32-6-2. Michigan lured Yost with a salary of $2,300, more than twice what Stanford paid him. Also, the university picked up the tab for all his living and eating expenses in Ann Arbor from September 1 to the end of the football season.

Yost did not inherit a downtrodden program.

The Wolverines' cumulative record the previous five years, which coincided with Michigan's membership in the new Western Conference, was 33-4-1.

Yost enjoyed success from the beginning in Ann Arbor. His first Maize and Blue squad finished 10-0 to tie for first in the conference with Wisconsin, whom they did not play. The Wolverines outscored the opposition 270-0.

The season ended with a trip to Pasadena CA to play in the first Rose Bowl on January 1, 1902. The game proved to be no contest. Stanford might have been the champions of the Pacific Coast Conference, but they were no match for the Wolverines and their "hurry-up" offense. The final score was 49-0.

Fielding Harris "Hurry Up" Yost is the most interesting character in the early history of college football with the possible exception of Knute Rockne. According to legendary writer Ring Lardner, Yost had "more personality than any other man I have ever met." In Natural Enemies: The Notre Dame-Michigan Football Feud, John Kryk writes: "Yost's most fascinating–and irritating–trait was his unrestrained penchant for bragging. He was an 'unabashed ham' who positively adored the spotlight. ... Yost was forever downplaying his opponents' accomplishments and boasting about those of his own team ..." Such a character simultanously produced undying loyalty in his own players and fans and rabid hatred in his rivals. But even his enemies had to admit that Yost was "a wily tactician, a brilliant innovator, and an incredibly fierce competitor."

Yost's team featured what today is called the "hurry up" or "no huddle" offense. His superbly conditioned athletes would run a play, sprint to the new line of scrimmage, and quickly run another–sometimes the same play five or six times in a row. Rare was the team that had athletes who could keep pace.

Michigan's star back Willie Heston described how the "Hurry Up Offense" worked. "Quarterback (Harrison) Weeks would call the next play (by number) as soon as the current play was over. At the line of scrimmage, Weeks would call out numbers, but that first number was the one to 'go' on. If the opposing team caught on, the system was changed. The Michigan players would not move on the signal, and the opposing team would be off-side."

The '02 Wolverines continued their mind-boggling streak. None of their first six opponents came within 23 points of them and only one of them scored any points–six.

1902 Michigan Wolverines (University of Michigan Michiganensian Yearbook Class of 1903)

Coach Yost is just to the right of the player holding the football.

Featured Player

Willie Heston came to Michigan in 1901 all the way from San Jose State Normal School in California, where he enrolled in 1898 with the intent of becoming a teacher. He immediately became a football sensation, wowing opponents and spectators with his long runs although his exploits on the West Coast did not attract nationwide attention. Heston was only 5'8" but weighed 190lb and could run the 100y dash in ten seconds. Among those who saw him play was Fielding Yost, the Stanford coach in 1900.

Willie earned his teaching degree and accepted a teaching job in Oregon for 1901. But his plans took an unexpected turn.

When Yost took the Michigan job in 1901, he wrote Heston to invite him to join the Wolverines and study law. With the National Collegiate Athletic Association still five years away, there were no rules prohibiting Willie from playing four more years of college football.

During Willie's four years at Michigan, the Wolverines had four of the most successful seasons in the history of college football. Michigan compiled a record of 43-0-1, outscoring its opponents by an astounding 2,326-40.

Heston returned to the West Coast with his Michigan teammates for the inaugural Tournament of Roses football game on January 1, 1902. Willie rushed for 170y on 18 carries as the Wolverines clobbered Stanford 49-0. That total remained the Rose Bowl record for most rushing yards for 59 years. |

|

| Heston became known for his quick starts and an uncanny ability to pivot and switch direction at full speed. He had "terrific driving power in his legs" and "a powerful stiff arm." Heston is considered the first "tailback" in college football. Previously, left halfbacks ran plays in one direction, and right halfbacks ran plays in the other direction. Yost placed Heston directly behind the center so that he could run in either direction. Yost also considered Heston "one of the greatest defensive backs, one of the hardest, surest tacklers that ever lived." Heston was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1953. | |

Could anyone derail the Michigan express? The next opponent, Wisconsin, believed they could. Philip King had built a strong program in Madison starting in 1896. Through the 1901 season, the Badgers were 41-6-1 under King. They had played Michigan once, defeating the Wolverines 17-5 in 1899.

The 1901 Badgers went 9-0, outscoring their opponents 317-5, and tied with Michigan for the conference title since the two teams did not meet. Neither school was satisfied with that outcome. So a game was scheduled for 1902.

King scouted the Michigan-Indiana game along with his FB Earl Driver. King was justifiably concerned. "Michigan is playing a very fast game, and the team is much further advanced in the game at this time than is Wisconsin. We realize, and have realized, that we have a very hard proposition to meet on November 1."

1902 Wisconsin Badgers (University of Wisconsin Madison Badger Yearbook Class of 1904)

Coach King is at the far left in the last row.

The game, much to the chagrin of University of Chicago coach Amos Alonzo Stagg, would be played in Chicago at Marshall Field on his campus. Home to numerous graduates of both Wisconsin and Michigan, Chicago was fertile recruiting territory for both schools. So while the game was ostensibly moved to Chicago to accommodate a larger crowd, it also gave Stagg's two biggest rivals a chance to show their programs to high school football players in the Windy City.

Marshall Field during a 1900 game

Wisconsin knew they would have to be at their best to beat the Wolverines. The Badgers dispatched Kansas 38-0 to move to 5-0 heading into the big clash in Chicago. But a Kansas player who had played for Yost when he coached the 1899 team told a reporter, "Wisconsin plays a good game, but she'll have to play faster than that to beat Michigan."

One writer opined that the Badger defense was "the best that has been shown by a Wisconsin eleven in years. The general opinion is that the line is absolutely impregnable, and that Michigan will be unable to break it down or to get around the ends." Also, "King has been quietly adopting some of the styles of play in which Michigan excels, one being the tackle back play ... The coach has also perfected a number of trick plays, which will be tried for the first time in the big contest. If Wisconsin ... can get within striking distance of Michigan's goal, Captain Juneau will try drop kicks from the field."

However, word of UM's 86-0 slaughter of Ohio State sent a wave of gloom through the Wisconsin camp. King would have to work hard to instill confidence in his men. To make matters worse, two Wisconsin stalwarts suffered from leg injuries: FB Driver and Captain W. J. Juneau.

Yost knew the Badgers would be by far his most formidable foe of the season. So Michigan practiced in "absolute secrecy ... behind the high board fence at Ferry Field ..." Yost was reported to be concerned that his team was "too confident." He told his players that they had not met as good a team as Wisconsin the last two years.

UM lineman Joe Maddock was expected to miss the game "on account of a boil on his hand" and a sprained wrist. Star HB Willie Heston nearly bit his tongue in half during the Ohio State game. As a result, he couldn't eat but "must hold back his head and be fed gruel beef broth and milk." However, he was expected to play Saturday.

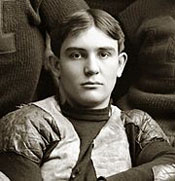

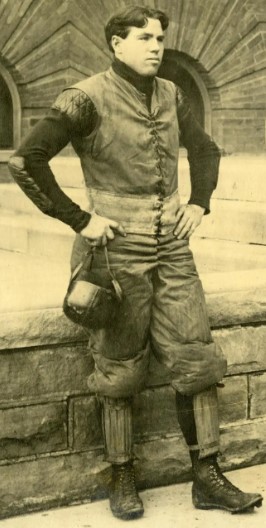

L-R: Harrison Weeks, Joe Maddock, Albert Herrstein

(Bentley Historical Library University of Michigan)

Both schools sent their gladiators off to Chicago with pep rallies. Wisconsin's Thursday practice was witnessed by an estimated 1500 people, "a larger crowd ... than has attended any of the home games this year. The students marched from the gymnasium to the field, headed by the university band, and watched the play of the team with great interest, cheering the men at every good play made."

In Ann Arbor, "Every student of the university turned out to a big singing meeting held in University hall" Thursday night. "Songs, red-hot speeches, thundering yells and, in short, every form of expression of Michigan enthusiasm was the order, and combined to make the meeting one of the most enthusiastic demonstrations of spirit seen at Michigan in some time. Professor Trueblood was on hand to lead the locomotive yell which has met with such popularity. This yell is designed to drown out the Wisconsin yell."

The betting line ended at seven to six in favor of the Wolverines. Those betting on Wisconsin pointed out that, while Michigan had rolled up phenomenal scores the last two years, neither her offense nor her defense had been severely tested. Most of the Wolverine scores came on long end runs by Heston and Herrstein. But the Badger ends, Abbott and Juneau, were strong enough to stop those plays.

Coach King promised his squad was ready. "The men are all in good condition and will fight the game of their lives tomorrow." Yost sounded less confident. "The man who thinks Michigan has a cinch does not know what he is talking about. If we are defeated, it will be mainly due to overconfidence, a spirit that is so manifest I cannot break it up."

A report the day before the game said, "Rooters from Ann Arbor and Madison are in Chicago in force, thronging the hotel lobbies and parading the streets bedecked with ribbons and taunting banners. There is more enthusiasm among rooters than seen in years."

When trains carrying 1,500 Wisconsin students arrived shortly before noon Saturday, the band led a parade along downtown streets in the Windy City.

When trains carrying 1,500 Wisconsin students arrived shortly before noon Saturday, the band led a parade along downtown streets in the Windy City.

A crowd estimated at 22,000, the largest at a college football game in the west, overflowed Marshall Field on an unseasonably warm, overcast day. Attendance could have been higher, but the gates were closed when Chicago football "manager" Barleme cut off ticket sales after an unfortunate incident during the first half injured a number of people, as will be explained in due time. Many of those turned away watched from the roofs of nearby buildings. "By the time the second half began, there was not an unoccupied roof, telegraph pole, lamp post or window within eyesight of the gridiron."

Hundreds of football enthusiasts in Kalamazoo MI gathered around the bulletin board of the Gazette-News to follow the game via reports from Chicago.

Even in neutral-state Minneapolis, a large crowd gathered to follow the game via "special wire service direct from Marshall Field" to the offices of The Minneapolis Journal.

Even in neutral-state Minneapolis, a large crowd gathered to follow the game via "special wire service direct from Marshall Field" to the offices of The Minneapolis Journal.

The game consisted of two 35-minute halves.

One of Yost's oft-quoted axioms was, "Hurry up and score in the first few minutes of a game before your opponents realize what is going on." To that end, he ran what today would be called a "no huddle offense." All eleven starters, every one in excellent physical condition, followed the ball downfield each play and started lining up for the next snap even before the pile was untangled. QB Harrison "Boss" Weeks often called the signals for the next play while the defense was hustling into position. Sometimes the Wolverines would run four or five plays without a signal–similar to today's "scripted" drives. The team was so well prepared that, as Heston recalled, "everyone knew what to do and what play was coming up. Our opponents didn't have much of a chance to get set for us."

The most popular offensive set in 1902 was the "tackles-back" formation. With only five players required on the line of scrimmage, the two tackles lined up in the backfield. (Some teams used the "guards-back" formation instead of or in addition to the tackles-back.) From that starting point, one tackle could lead the runner while the other lagged behind him and pushed him forward or even grabbed the leather straps (handles) sewn into the shoulders of the jersey or on the hips of their trousers and dragged or even threw the ball carrier forward. Sometimes the tackles carried the ball.

As is still true today, only one backfield player could be in motion at the snap, and he could not be moving forward at the snap. However, teams had three downs to gain five yards. (Hence the striping of the field every five yards as is still the case today.) Forward passes were illegal until 1906. Three officials worked each game.

Michigan-Wisconsin action 1902 (tiptop25.com)

Michigan Starts Strong

The Wolverines took the opening kickoff and moved right down the field. King expected Michigan to use the strategy that had worked well all year–mostly end runs mixed with occasional up-the-middle plunges. But Yost, sensing what King was thinking and convinced his line was stronger than the Badger forwards, had QB Weeks run play after play up the gut. To facilitate that strategy, Yost started Paul Jones at fullback instead of the speedier but smaller James Lawrence.

Starting from their 35 after Curtis Redden returned the kickoff 10y, Wisconsin held for two plays, but Michigan gained a first down on a fake kick. Again the Badgers forced third down only to have Albert Hernnstein push through the center for 3y to allow UM to retain possession. In a display of "the fastest kind of ball," a 5y gain around right end was followed by eight more around left end. Hernnstein skirted left end for 15y to the 20. When the Wolverines reached the three, T Joe Maddock, starting despite his boil, rammed over the goal line. Everett Sweeley "kicked goal" to make it 6-0 Michigan after eight minutes of play.

At least the exhausted Badgers would get the ball–right? No. The rules required the team that was scored on to kickoff to the scoring team. The kick reached the UM goal line. So the Wolverines started their second possession at their 20. After Hester ran around left end for 5y, Weeks followed the custom of the day by punting the ball to midfield.

More Michigan-Wisconsin action (Michiganensian Yearbook Class of 1903)

After gaining 2y, then losing one, Wisconsin went for it on third down and made it. But no such luck for the Badgers on the next series. So they punted to the 10, the pigskin being returned to the 25. An injured Michigan man was replaced–the only way a substitute could take the field following the tradition of rugby and soccer.

Michigan Thwarted by Fumble

UM began another drive deep into UW territory. Jones, "a human battering ram in the hands of his teammates," pushed up the middle twice before "another man is laid out." From the UW 35, Hernnstein raced around left end for 15y, suffering a cut over his eye for his trouble. Jones and Maddock smashed the middle, making just enough to retain possession.

About this time, a commotion broke out on the northeast corner of the field. A temporary bleacher built to hold 400 people but filled with 500 collapsed, causing the game to be stopped for a few minutes. Several hundred people were thrown to the ground. "A score of men" were injured, many with broken limbs, but no one was killed. With the police occupied with the accident, the immense crowd broke down the wire fence and swarmed onto the field. But the "scrubs" of each team came to the rescue, shoving the crowd away from the sidelines so the game could resume after a 15-minute delay.

When play resumed, Michigan continued its march deep into UW territory again. Jones +3, Palmer +4, and Jones +3 before Heston again skirted Bush's end to the 10. But the drive abruptly ended with a fumble.

Badgers Repel Threat

Juneau broke free for Wisconsin's first long gain of the day–30y. But Michigan held and Redden returned 15y to the center of the field. UM then lost the ball because of a holding penalty but got it back two plays later on a punt, Sweeley taking the ball out of bounds at the 25. The Wolverines resumed their smashing runs and quickly moved to midfield. Three runs by Hernnstein and Heston gained 12 through tackle. Then Jones gained three at right tackle, and Palmer and Maddock added 15 more. Jones was "laid out for several minutes" at this point but stayed in the game. Heston ran into LE Allen Abbott "like an avalanche" to put the ball on the five. UW partisans held their breath since another UM touchdown would put the game out of reach. Heston moved the pigskin to the one, but the beleaguered Badgers dug in and stopped Jones to take over on downs. "A mass play was hurled against Long and Abbott. When the scrimmage was over, breathless Wisconsin 'rooters' of second life sent up a mighty cheer. Their line at last had held."

UW immediately "punted out," but Michigan fumbled the kick, a Badger recovering. It was time for the Red and White to do some smashing of its own. Liljequist gained before Vanderboom did the same. Then Juneau ran around Sweeley's end to midfield, where he fumbled. But Abbott pounced on it at the UW 45. Neither team threatened the rest of the way.

The half ended with Wisconsin in possession on its 10. MICHIGAN 6 WISCONSIN 0

Michigan outgained the Badgers in the first half 273-75.

.jpg)

L-R: Everett Sweeley, James Lawrence, Curtis Redden

Badgers Repel Threat

Michigan's Lawrence, in for Jones at fullback, kicked off to Juneau, who returned the ball to midfield. UW gained a quick first down on Abbott's 5y scamper and Juneau's 4y run around Sweeley. But Vanderboom fumbled after gaining five to turn the ball over to Michigan. The Badgers, who moved their halfbacks inside their ends for the second half, gave ground grudgingly, several times forcing Yost's men to take the full three downs to gain the five to keep possession. Then Abbott threw Hernnstein for a 2y loss. When Heston gained only one, Lawrence tried a place kick from the 45 that didn't come close. Earl Driver "took the free kick from the 20y line and kicked to Redden on Michigan's 50y line, and he carried it back ten yards." The teams exchanged possession of the ball within 10y of the midfield stripe on either side until Driver punted to Hernnstein on the UM 20 where he was "thrown in his tracks."

After three more punts, Weeks tried "a quarterback kick" that was blocked by Long. But Wisconsin could go nowhere and punted. Michigan seemed content to run out the clock–to use a phrase not in vogue at the time. Hernnstein tried a fake kick but gained only a yard. UW made one first down after receiving a punt but had to kick back three plays later. Michigan moved close enough for Lawrence to miss another place kick from the 25.

Driver kicked right back to Graver, who returned 23y to the 27 "by a brilliant run." But two plunges gained only one. So Lawrence tried and failed again, this time from a bad angle at the 25. Michigan got the ball right back, recovering Juneau's fumble at the 30.

But all that gained the Maize and Blue was another missed field goal by Lawrence. Wisconsin didn't want the hot potato and kicked to the center of the field to Weeks, who was thrown after failing on a fair catch. After gaining 15y, Michigan tried another "free kick for goal" from the 35, but Lawrence went 0-for-5.

Minutes later "the game was called" with the ball in Michigan's possession "on its own fifty-yard line." FINAL SCORE: MICHIGAN 6 WISCONSIN 0

Michigan outgained the Badgers 92-48 in the second half for a total advantage of 365-123.

Post-game

Weeks: "I am almost too happy to talk. It was an awful hard game. We should have had two more touchdowns in the first half. My poor judgment kept us from scoring oftener. Our defense certainly impressed Wisconsin. They caught us napping several times and drew our ends in, but on the whole our defense was good. We are all tickled to death at the result."

Coach King: "I think that the better team won. Our boys played a good game, and I am proud of them. It is not a disgrace to be beaten by such a team as Michigan has. The men are all in good conditions. Taking it all in all, it was indeed a great game."

Captain Juneau of Wisconsin: "Oh, but it was a glorious game. I am indeed very happy. The score should have been 18 to 0. They expected us to play our halfbacks outside of tackle. We surprised them a few, didn't we? I told the team to pound away as long as they could and to pound hard. They pounded hard enough to satisfy even Wisconsin, I think. We surprised them on the defensive. However, their defense, too, was a little stronger than I expected."

The Chicago Tribune writer summarized the game like this: "Michigan showed the most powerful and concerted attack ever seen in western football. Few of the immense crowd knew that they were witnessing the acme of modern attack. But the football critics and galaxy of western coaches, drawn from far and wide to see the battle of gridiron giants, marveled at the perfection of unified effort which Yost had taught, and his pupils so ably carried out. It was better offense than the Michigan team of 1901, which registered 550 points without being scored on, showed in its best games last year. This is a bold statement but it was the unanimous opinion of those whose business it is to study football for practical uses."

Former Penn coach George Woodruff, the inventor of the guards-back plays and other innovations, wrote an analysis column for the Tribune: "For two years I have been curious to see the Michigan team play. I was filled with doubts as to whether it was really as strong in material and in style of play as scores would seem to indicate. My curiosity was gratified yesterday at Marshall field ... That

the team is great goes without saying. That it is phenomenal against second class elevens is equally apparent from the scores of the last two seasons. And yet I hesitate to admit that the Wolverines could beat many first class teams which I have seen. As examples I would note the Pennsylvania eleven of 1897, the Yale team of 1900, and the Harvard team of 1901. My hesitancy about the relative merits of Yost's men and teams named above is an evidence that I consider Michigan of both 1901 and 1902 in the front rank of all football teams. ... I believe western teams rank with those in the east. The best here are evenly matched with the best there."

References:

College Football U.S.A. 1969 ... 1972: The Official Book of the National Football Foundation, John McCallum and Charles H. Pearson (1972)

Natural Enemies: The Notre Dame-Michigan Football Feud, John Kryk (1994)

Michigan Football, Martin Gitlin (2014)

Stagg vs. Yost: The Birth of Cutthroat Football, John Kryk (2015)

The Unanimous Champions of College Football, 1869-2019, Robert J. Reid (2022)

College Football U.S.A. 1969 ... 1972: The Official Book of the National Football Foundation, John McCallum and Charles H. Pearson (1972)

Natural Enemies: The Notre Dame-Michigan Football Feud, John Kryk (1994)

Michigan Football, Martin Gitlin (2014)

Stagg vs. Yost: The Birth of Cutthroat Football, John Kryk (2015)

The Unanimous Champions of College Football, 1869-2019, Robert J. Reid (2022)