|

Basketball

Snapshots – Part 2

The Path to 24 Seconds - I

The NBA swam upstream the first six years of its existence (1947-1954).

- Overshadowed by the college game, the league struggled to gain recognition in the northeast, where all its franchises were located, and had almost zero visibility in the other sections of the country.

- Founded by a group of arena owners looking to fill winter dates between hockey and boxing events, the league offered a rough, foul-plagued, boring brand of basketball.

Several games illustrate the league's plight. The first is the infamous playoff game between the New York Knicks and the Baltimore Bullets on Saturday night, March 26, 1949.

- Joe Lapchick's Knicks hosted the Bullets, headed by player-coach Buddy Jeannette, in the third and final game of their Eastern Division Series B playoff. The winner would qualify to meet the Washington Capitols in another best-of-three.

- Each team had won on the other's court. The New Yorkers lost an 82-81 "thrill-packed encounter" in the first game before registering a "convincing" 84-74 triumph to tie the series.

- Louis Effrat summarized the rubber game in the New York Times like this:

In the wildest basketball game ever played at Madison Square Garden the New York Knickerbockers last night defeated the Baltimore Bullets, 103-99, in overtime. ... Exactly 100 personal fouls were called, eleven men were banished, punches were thrown by players and spectators and none among the crowd of 9,625 ever will know why the affair did not terminate in a riotous free-for-all. ... The referees, Hagan Andersen and Ed Boyle, were unable completely to control the participants.

- According to Effrat, "all the feverish whistle-blowing" was caused by "the blocking, tackling, hooking and hacking tactics of both sides ..." He also described the play as "ragged, though rugged."

Reiser attempts to take ball away from Lumpp as Lewis (5) and

Tanenbaum (background) of Baltimore close in. ( NY Times photo)

- With one second to play in regulation, Connie Simmons of the Bullets stepped to the FT line and, "undaunted by the unsportsmanlike jeering of the crowd," canned two to tie the game for the 21st time, 89-89.

- Ray Lumpp and Butch Van Breda Kolff - later coach of the Lakers as well as the New Orleans Pride of the Women's Basketball League - led the Knick victory in the OT.

- Six Bullets fouled out, leaving them with only four on the court in the last minutes of OT. The Knicks lost five of their eleven squadmen to the six foul limit during the three-hour marathon.

- Altogether, the two squads shot an incredible 118 foul shots, a playoff record until Boston and Syracuse shot 128 in 4 OT four years later in another example of the pros' rugged style of play that resembled football as much as basketball.

- Remember that, at that time, every foul produced FTs, one or two depending on whether the player was in the act of shooting. It's no wonder the Knicks-Bullets game lasted an agonizing three hours including the interruptions produced by three full-blown fistfights.

- Each team scored 26 FG, but the Knicks made 51 FT compared to 47 for Baltimore to account for the final difference.

If this contest had an overabundance of "action" of the wrong kind, the next games we will cite as symptomatic of the league's problems illustrate the opposite problem - too little action.

Continued below ...

Reference: Tall Tales: The Glory Years of the NBA, in the words of the Men Who Played, Coached, and Built Pro Basketball, Terry Pluto (1992)

Top of Page |

Joe Lapchick

Buddy Jeannette

Connie Simmons

Butch Van Breda Kolff

|

George Mikan

Murray Mendenhall

Larry Foust

Ralph Beard

|

The Path to 24 Seconds - II

The early NBA suffered from the lack of a shot clock, as illustrated by these two games, among others.

November 22, 1950: Fort Wayne @ Minneapolis

- The Pistons handed the Lakers their first loss at home in nearly a year, 19-18. The two teams combined for only 31 shots in 48 minutes of play. Only eight FGs were successful.

- Minneapolis's 6'10" 245 lb C George Mikan had all four fielders and 15 of the team's 18 points. No other Laker attempted more than two shots. The Q4 score was Fort Wayne 3, Minneapolis 1.

- It was Mikan's dominance that led the Lakers to back-to-back championships in 1948-9 and 1949-50 and caused Pistons coach Murray Mendenhall to adopt his stall strategy. "I've been trying for three years to do something about him, but nothing works," Murray said.

- The visitors controlled the tip and Mikan and his teammates moved into their defensive positions. But when they turned around, they saw Pistons C Larry Foust standing at midcourt with the ball on his hip. Mendenhall had ordered him to do nothing until the Lakers came out to play man-to-man. The officials ordered Mendenhall to play ball, but he charged that the Lakers played an illegal zone that kept Mikan under the goal.

- The crowd of 7,021 began to boo and stomp their feet, but Fort Wayne held the ball for as long as three minutes at a time. When one player got tired of holding the ball, he'd flip it to a teammate.

- Every so often, Laker G Slater Martin would press and try to force a turnover. When he was successful, the Lakers would hurry downcourt and, after no more than three passes - the last one usually to Mikan - put up a shot.

- Fort Wayne led 8-7 at the end of Q1 but the Lakers "rallied" to carry a 13-11 edge into the locker room. Mikan had scored 12 of the 13.

- The Pistons continued their tactics even though they trailed. Lakers F Vern Mikkelsen thought, "As long as we were ahead and they were holding the ball, there was no point in our trying to create anything." Fort Wayne outscored the home team 5-4 in the quarter to trail by only one entering the final period.

- The teams exchanged FTs, and the score stayed 18-17 Lakers into the final minute. Now it was the home team's turn to stall as the Pistons tried to get the ball back. With nine seconds left, FW forced a turnover as an errant Laker pass sailed out of bounds.

- The Pistons passed in to Curly Armstrong who fed the breaking Foust who tossed a running hook shot over Mikan to make it 19-18. The Lakers hurried downcourt, but Martin's shot hit the rim as the horn sounded to end the lowest-scoring game in NBA history.

The second game that revealed the NBA's serious rule problems came a few weeks later.

January 6, 1951: Indianapolis Olympians @ Rochester Royals

- The Royals and Olympians tied 67-67 at the end of regulation. That doesn't seem like a game with a slow down problem, although Q4 produced only 20 points, the Royals outscoring the Olympians 12-8.

- No, it was the six OTs that spoiled the evening for the 3,790 fans. Two of the extra five-minute periods were scoreless as both teams concentrated on freezing the ball for one shot. In one of the OTs, neither club launched a shot.

- Two of the OTs produced 2-2 standoffs and one was 4-4. Finally, Indy's Ralph Beard sank a breakaway layup in the last second for the only points in the sixth extra session and a 75-73 victory in what is still the longest game in NBA history.

Something had to be done. But it took several more years before someone suggested a shot clock.

Continued below ...

Reference: Tall Tales: The Glory Years of the NBA, in the words of the Men Who Played, Coached, and Built Pro Basketball, Terry Pluto (1992)

|

The Path to 24 Seconds - III

Leonard Koppett

Bill Sharman

Ray Felix

Jack Molinas

Lakers-Nationals NBA Finals 1954

Video of 1954 Finals

|

Leonard Koppett (24 Seconds to Shoot: The Birth and Improbable Rise of the NBA) attributed the "bruising, body-contact type of game" that characterized the early years of the NBA to three factors.

- The first, and foremost, was the test of manhood: as soon as possible, pros "put the question" (as [Knicks coach Joe] Lapchick liked to say) to all newcomers. How much guts did the newcomer have? How much pain and risk was he willing to undertake to complete the path to the basket when it opened up? Could he be made to lose his temper, and therefore lose control of his own game? ...

Establishing respect, therefore, was necessity number one for every new player - respect from the opposition, and from his own teammates for the way he responded to the opposition's pressure. And the only way to establish respect was to hit back, promptly and effectively - to give as good as one got. ...

- The second basic invitation to rough stuff was strategic. Obviously the referees couldn't see everything, and couldn't call everything they did see. If they did, the whole game would quickly become a parade to the foul line, nullifying the very thing the owners were trying to sell - high speed, college-style basketball. Referees who had worked with pros before knew how to be "intelligently selective"; those recruited from the college ranks learned quickly, or went back to college games. ...

- The third factor was embedded in the rules, and was as much of a problem in college and amateur basketball as in the pros: as a close game came nearer and nearer to the final buzzer, there were substantial tactical advantages to fouling. The fact that a basket was worth two points and a free throw only one made it worthwhile to try to trade a foul - which could cost one point - for a chance to score two points. ...

The fledgling NBA tried new rules every year to address the problem of stalling by the team in the lead late in the game and the consequent fouling by the opponent. The 1949-50 season, for example, averaged 54 fouls per game, or more than one a minute.

- 1950-51: A jump ball would be held after each foul shot in the three minutes of the game. The change was intended to discourage the defense from fouling since they would not automatically get the ball after a made FT. The jump pitted the player who was fouled against the player who fouled him. Coaches soon figured out that the best strategy was to have a big guy foul a small guy.

- 1951-52: The lane was widened from 6' to 12' to blunt the impact of big men, primarily George Mikan of the Minneapolis Lakers, and open more driving room to the basket. The jump ball rule was modified to go into effect in the last two minutes.

- 1952-53: The jump ball rule was amended again so that the player fouled would jump against the opponent who usually guarded him. This put the onus on the already overburdened officials to keep track of who was guarding whom.

- 1953-54: Players were allowed only two fouls per quarter (with the limit of six per game as enacted at the beginning of the league in 1946-7). If a player committed a third foul in a period, he must sit out the remainder of the quarter. The rule did little to lessen late game fouling.

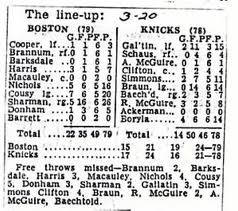

The inefficacy of the rules changes was demonstrated March 20, 1954 to a nationwide TV audience on the DuMont Television Network.

- The first paragraph of the AP article on the game played before 10,751 in the Boston Garden makes it sound like an exciting contest that would showcase pro basketball to the nation.

The Boston Celtics edged the New York Knickerbockers, 79-78, to eliminate the New Yorkers from the Eastern Division playoffs ... A basket by Bill Sharman with only 17 seconds left gave the Celtics their second victory of the eastern playoffs and sent New York down to its third straight playoff defeat.

- But if you read further, you learn that referees Charley Eckman and Gig Nicol called a total of 95 fouls, 49 against Boston. The Celtics won despite making only 35 of 56 FTs while the Knicks canned 50 of 63. That's right - 119 FTs were shot. And who knows how many times the officials ignored less blatant contact just to keep the game moving.

- The final quarter took 45 minutes to play. In fact, the Knicks' desperate attempts to sink a basket in the last seconds were not seen by television fans because the wire connection was disconnected when the fray reached the three-hour broadcast limit.

- Koppett: The game encompassed all the repulsive features of the grab-and-hold philosophy. ... The arguments with the referees were interminable and degrading. What had been happening, as a matter of course, in dozens of games for the last couple of years, was shown to a nationwide audience in unadulterated impurity.

- That same day, the Fort Wayne Pistons and Minneapolis Lakers demonstrated NBA basketball at its best in a Western Division playoff game in which only 31 fouls were whistled, the Lakers winning 78-73. But only the 2,600 in the arena experienced the excitement.

The 1953-4 season had started promisingly.

- Exciting new players had entered the league via the draft, such as 6'11" Ray Felix from Long Island U. (who had not been implicated in the betting scandal that destroyed that school's basketball program); F/C Bob Houbregs from Washington; F Jack Molinas, Columbia; and G/F Frank Ramsey, Kentucky.

- Molinas lasted only until December when he was found to have bet on his own team and immediately barred from the league. Commissioner Maurice Podoloff's decisive action gave the NBA credibility in an era that had just experienced major college gambling scandals.

- The third annual All Star Game at Madison Square Garden January 21 brought the 20 greatest players in the world together for an exciting OT contest that had basketball fans buzzing for weeks.

- Both the Eastern and Western Division races went to the wire. The Knicks edged the Celtics and Syracuse Nationals by two games in the East while the Lakers copped the West by a similar margin.

Then the playoffs left a bad taste in everyone's mouth.

- After the Celtics-Knicks debacle, two small market teams (to use a term not in vogue at the time), Minneapolis and Syracuse, battled their way to the finals.

- The Lakers claimed their fifth championship in six years in a seven-game finale that failed to push the baseball spring training reports off page one of the nation's sports sections.

- Also, the final tally showed that the nine teams had averaged 79.5 points per game, the lowest since the league's second season (1947-48).

- Three of the nine franchises were on life support: Baltimore, Fort Wayne, and Milwaukee.

When the owners met less than two weeks after the playoffs, the future looked bleak.

Continued below ...

References: 24 Seconds to Shoot: The Birth and Improbable Rise of the NBA, Leonard Koppett (1968)

Tall Tales: The Glory Years of the NBA, in the Words of the Men Who Played, Coached, and Built Pro Basketball, Terry Pluto (1992)

|

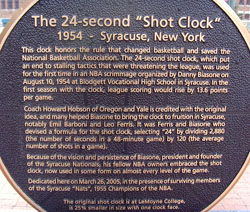

Danny Biasone

Monument in Syracuse showing the original 24-second shot clock; the building in the background is the original armory - now a science museum - where the Nationals played their games

Plaque on the monument

Shot clock today

Dolph Schayes

Johnny "Red" Kerr

George Yardley

|

The Path to 24 Seconds - IV

You wouldn't think a childhood immigrant from Italy would play a crucial role in the history of pro basketball. But Danny Biasone did just that.

- "This short, somewhat dour, rather unpolished man" (to quote Leonard Koppett), owned a bowling alley in Syracuse, one of the small city outposts of the original NBA along with Rochester, Fort Wayne, and Minneapolis. Since 1946, the 5'6" Biasone had also owned the Syracuse Nationals.

- Always struggling to make a profit, Danny despised the rough and tumble, slow style of play prevalent in the league because it bored the fans and therefore kept them out of the arenas.

- As early as 1951, Biasone began pushing an idea championed by Oregon coach Howard Hobson (among others) - a shot clock to limit possessions.

- But Little Danny couldn't get the attention of the other owners, who followed the leadership of the big market magnates in New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Washington.

Finally, the owners met on April 22, 1954 knowing that the NBA was at a crossroads. Bill Simmons summarized the league's plight as follows.

Without rules to prevent intentional fouling, stalling and roughhouse play, league scoring dropped to an appalling 79.5 points per game. ... If you were protecting a lead, your point guard dribbled around and waited to get fouled. If you were intentionally fouling someone, you popped him to send a statement. Players fought like hockey thugs, fans frequently threw things on the court and nobody could figure out how to stop what was happening. ... The '53 Playoffs averaged an unbelievable eighty free throws per game. The anti-electrifying '54 Finals featured scores of 79-68, 62-60, 81-67, 80-69, 84-73, 65-63, and 87-80. You get the idea.

- Additionally, the league had endured its first brush with the gambling scandals that had plagued college basketball the last few years with a rookie being banned for betting on his own team.

The owners finally listened to Danny.

- He proposed that, each time a team gained possession of the ball, it had to take a shot within 24 seconds.

- How did he arrive at 24 seconds? Simple. He divided the average number of shots taken in a "typical game" into the 2880 seconds (48 minutes) of playing time.

- Considering the league had in fact averaged one shot every 18 seconds, the rule gave a reasonable amount of time to get into the frontcourt and run a play.

But the 24-second rule alone would not eliminate all the intentional fouling. As Koppett explained:

A time limit, by itself, might encourage more fouling. If the offense had to shoot within 24 seconds, it might be a good idea to foul it first, and give up one point instead of two. Some way had to be found to nullify the strategic advantage of fouling.

- The answer was a limit on team fouls. To that point, the only limitation was on individual players - six fouls disqualified the man from further play in the game.

- Now the owners passed a rule stating that after the sixth foul by a team in a quarter, every additional foul would earn an extra free throw. So a "common" one-shot foul would lead to two FTs, and a foul on a shooter would give him three chances to make two points.

- So the strategy of trading one foul shot for the chance to make a FG no longer held any attraction. It was better for the losing team in the late minutes to play good defense to force a missed FG during each 24 second possession.

- The owners also had the good sense to realize that offensive fouls - obviously not deliberate since they cost a team possession - should still count toward the offender's personal limit but should not count as team fouls.

- One further refinement called for two shots for each backcourt foul. This delayed until the final minute the strategy of fouling an offensive player as soon as his team gained possession in order to get the ball back quicker.

- As Koppett summarized:

In one meeting, the NBA owners accomplished more than they had in eight years, although the magnitude of their achievement was not seen at the time, even by them.

The 1954-5 season featured the brand of ball that persists in the NBA to this day.

- In addition to ending the continual fouling in the last minutes, the 24-second rule had an unanticipated effect on the game. Koppett:

One thing, it had to be admitted, was gone along with the destructive tactics: a set, deliberate offense, of the short the Lakers had used. If a team moved into position slowly, to set up someone like [6'10" George] Mikan, there really wasn't enough time left to run a play or two. The new rules definitely favored a running club, and anybody who didn't have a good fast break had better think about getting one. ...

- The average points scored by each team jumped to 93.1, an increase of 13.6. In addition, the number of fouls dropped slightly. Koppett:

The first season under the 24-second rule had not revolutionized play - that would take about three years, while old habits were abandoned and new techniques explored. But it did, instantly, eliminate the bad taste that had been building up for so long. Finally, the emphasis had settled on where it always had to be if a league was to succeed - on the players and the games.

Fittingly, the rules changes Biasone championed benefitted his team in the final game of the season.

- The early rounds of the playoffs featured three OT games and four other close ones. None were marred by the stall-and-foul tactics prevalent in previous seasons.

- Syracuse reached the NBA finals against the Fort Wayne Pistons. The series went to the seventh game in Syracuse. The odds favored the Nats since the Pistons had lost all 27 games they had played in Syracuse since the inception of the NBA.

- Still, the law of averages finally seemed to be catching up with the Nats as the visitors jumped out to a 41-24 lead. As star Dolph Schayes recalled:

If it were a year earlier, the game would have been over. If there were no 24-second clock, they could have dribbled out the second half and shot free throws.

- Instead, Syracuse closed the gap and tied the game at the end of Q3. The teams traded the lead throughout the final quarter. At no time did either team hold the ball on offense or foul intentionally on defense.

- Finally, with 12 seconds to play, George King sank a FT to put the Nationals ahead 92-91. Then he stole the ball to preserve the victory and give Danny his first and last NBA title.

- Nationals C Johnny Kerr (longtime TV broadcaster for the Chicago Bulls):

For years, we kidded Danny Biasone that he invented the clock so he could win a title, but the clock did make the difference. In the first half, George Yardley and those guys were killing us.

Unfortunately, as the NBA grew, the league's prophet, Biasone, couldn't survive in a small market.

- So he sold the Nationals in 1963 to owners who moved them to Philadelphia to become the 76ers.

- He died at age 83 in 1992, largely forgotten. In the last days of his losing battle with cancer, he complained that the hospital wouldn't supply him with a tv to watch the NBA playoffs.

- The league sent a floral arrangement in the shape of a shot clock to the funeral.

- Danny was inducted posthumously into the Basketball Hall of Fame in 2000.

|

Reference: Tall Tales: The Glory Years of the NBA, in the words of the Men Who Played,

Coached, and Built Pro Basketball, Terry Pluto (1992)

24 Seconds to Shoot: The Birth and Improbable Rise of the NBA, Leonard Koppett (1968)

The Book of Basketball: The NBA According to The Sports Guy, Bill Simmons (2009) |

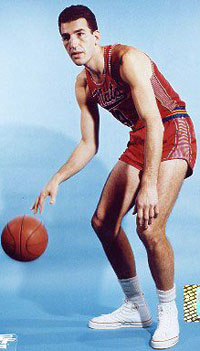

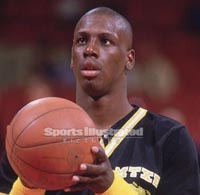

Xavier McDaniel became the first player in NCAA history to lead the country in scoring and rebounding in the same season.

- Born in South Carolina in 1963, the 6'7 F played for Wichita State from 1981-5.

- During his first two seasons in Wichita, the Shockers were on NCAA probation. He was a teammate his freshman year of Antoine Carr and Cliff Levingston.

- When Levingston left for the NBA, McDaniel became a starter and averaged 18.8 points and 14.4 rebounds as power F opposite Carr.

- Carr left the next season, and McDaniel raised his scoring average to 20.6 points per game to earn the Missouri Valley Conference MVP award.

- He then led the nation in scoring (27.4) and rebounding (15.0) his senior season. He finished with over 2,000 points and 1,000 rebounds.

- In college, Xavier began to shave both his head and his eyebrows to look more intimidating.

The Seattle Supersonics made McDaniel the #4 pick of the 1985 NBA Draft.

- Starting immediately, the "X-Man" averaged 17.1 ppg to finish second in the Rookie of the Year balloting behind Chuck Person.

- He averaged over 20 ppg each of the next three seasons.

- Early in the 1990-1 season, the Sonics traded McDaniel to Phoenix for Eddie Johnson and two draft picks.

- At the end of that season, the Suns passed him on to the Knicks where he fit well in Coach Pat Riley's physical style. His days in New York are best remembered for the intimidating D he played on Scottie Pippen during the Bulls' seven-game series victory that led to their second NBA crown.

- McDaniel played with the Celtics and New Jersey Nets on either side of a stint in Europe before retiring following the 1997-8 season.

Xavier has appeared in numerous tv shows since debuting in the movies in 1992.

|

Xavier McDaniel, Wichita State

Xavier McDaniel, Seattle

|

|

Luisetti's

One-Handed Shot

Angelo "Hank" Luisetti revolutionized the game of

basketball in the 1930s. How did he do it? By developing a running one-handed

shot. Players in Hank's time took two-handed set shots

with both feet on the floor. While accurate, the shot was easy to defend.

A player needed a solid screen to have time to get the shot off. As

a result, basketball scores were usually in the 30s, occasionally in

the 40s if one team were clearly superior.

Playing

for Stanford from 1936-8,

Luisetti scored 1,596 points (16.5 ppg), made All-American

all three years, and was voted Player of the Year twice. The game that

cemented his legacy took place December 29, 1936. Stanford

traveled cross-country to play Long Island

University at Madison Square Garden. Coach Claire

Bee's LIU team

had won 43 games in a row. The smug East Coast fans had heard about

Luisetti but wondered how he would stack up against

the pride of the East. They quickly found out. Hank

popped in 15 points to lead the West Coast quintet to a 45-31 upset

before 17,000 fans. In later years, Bee said, "I

can't remember anybody who could do more things."

|

Hank Luisetti

|

Another

highlight occurred on January 1, 1938, in Cleveland when Luisetti

scored 50 points against Duquesne,

making him the first player to reach the half-century mark. He made

23 FG and 4 FT. Hank still holds the Stanford

record for most points in a game.

Since

the NBA did not exist yet, Luisetti did not play

pro ball. World War II would have derailed his career anyway. A 1950

poll voted Hank the second best basketball player

of the first half century, behind only George Mikan.

Luisetti entered the Basketball Hall of Fame in 1959.

|

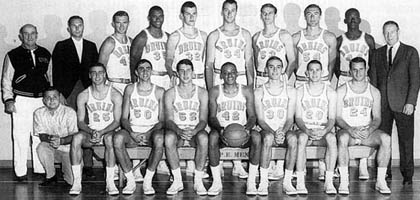

Wooden's First National Champs

This is a "before he was a legend" story about John

Wooden's first national champions at UCLA

in 1963-4. No Lew Alcindor (later Kareem Abdul-Jabbar)

or Bill Walton. This team was known as "gutty

little Bruins."

They

may have lacked the big athletic center, but they were a marvelous 30-0

team nonetheless. Oh, they had talent. Three starters later played in

the NBA: 6'2" senior Walt

Hazzard (#42), who later coached his alma mater, 6'1"

junior Gail

Goodrich (#25), and 6'5" junior Keith

Erickson (#53). The other two starters were 6'3" senior

Jack Hirsch (#50) and 6'5" senior Fred Slaughter

(#35). Sophomore Kenny Washington (#44), another future

pro, came off the bench.

Wooden

had started in Westwood in 1948-49. His NCAA record entering 1963-4

was:

- 1950:

Pacific Coast Conference champions, lost in NCAA first round

- 1952:

same as 1950

- 1956:

PCC champions, lost in NCAA first round to eventual champion San

Francisco with Bill Russell

- 1962:

Athletic Association of Western Universities champions, won the NCAA

Far West regional, lost to eventual champion Cincinnati

in Final Four

- 1963:

AAWU co-champs, lost in NCAA first round

The

Bruins were not even

picked to win the AAWU title in 1964 and ranked 11th in the preseason

AP poll. As they won game after game, they climbed in the rankings

until January when, as the only remaining undefeated team, they took

the top spot for the first time in history after Georgia

Tech beat Kentucky.

Combining quickness with excellent teamwork on both offense and defense,

UCLA swept through the

conference schedule unblemished. The closest call came on the second

night of a back-to-back at Cal,

58-56.

In

the 25-team NCAA tournament (not yet called "March Mardness"),

the Bruins won the West

Regional at Corvallis OR by defeating Seattle

(95-90) and San Francisco

(76-72). In the Final Four in Kansas City, they topped Kansas

State 90-84 (their third win over the Wildcats

that season) and then Duke

98-83 in the finals. Hazard was voted the tournament

MVP.

John

Wooden's record at UCLA

ended up as follows:

first 15 years (1949-1963): no national

championships

last 12 years (1964-1975): ten national

championships

So

a subtitle for this Snapshot might be "Sometimes it takes a long

time to become a legend."

|

The

Original Celtics – from New York, not Boston

Boston fans won't want to hear this, but the original

basketball Celtics were

a New York-based team. The first "Celtics"

were an all-Irish team (hence the name) that disbanded during World War

I. In 1918 promoter James Furey reformed the team with

some of the previous players plus others mostly from the West Side of

New York City. He haughtily called his team the

Original Celtics.

They

played in several struggling pro leagues before becoming primarily a

touring squad (similar to the Harlem Globetrotters,

who started in 1927). They traveled up to 150,000 miles a year playing

150 or more games. They won 90% of their games (193-11-1 one year).

In 1926, the American

Basketball League, brainchild of George Preston Marshall

(later the owner of the Washington Redskins),

forced the Celtics to

join his league by prohibiting member teams from playing them. Under

the heading of "be careful what you wish for," the Celtics

so dominated the league its first two seasons that the league broke

them up, apportioning their players to other teams. However, attendance

fell, accelerated by the Depression, and the ABL folded after the 1931

season. The Original Celtics

reformed as a touring team but never duplicated their original glory.

They finally disbanded in 1941.

The

Celtics of the 1920s

were enshrined as a team in the Basketball

Hall of Fame in 1959. They are credited with extending

the popularity of basketball throughout the nation as well as creating

strategies like post pivot play, zone defenses, and switching man-to-man

defenses. They were also the first professional team to sign players

to exclusive contracts.

Five Celtics

stars were inducted as Hall-of-Famers on their own.

-

Dutch

Dennert (6'1" 210 lb.), credited with perfecting

the pivot play; later coached several teams in pre-NBA leagues

-

Nat

Holman, a "dazzling passer" and accurate

shooter, the "best all-around player of the twenties"; coached City College of New York

for decades; in 1950 his team became the only college to win the

NCAA and NIT tournaments in the same season

-

John

Beckman, considered the "Babe Ruth of Basketball" (its premier attraction); a leading scorer who

electrified crowds

-

Joe

Lapchick (6'5"), "the game's first truly

agile big man"; a great passer and shooter who controlled nearly

every center tap that followed each made basket; successful college

coach at St. John's

with four NIT championships; also coached the New

York Knicks to three NBA Finals appearances

-

Bennie

Borgmann, "outstanding set shooter who could

also drive to the basket with great skill"; "pro basketball's

number one scorer in the 1920s"; later a pro player-coach and

then full-time coach

How

did the Celtics name,

associated with a New York team for over 20 years, end up the moniker

of the Boston franchise? Walter Brown, the first owner and one

of the founders of the Basketball Association of America in 1946 (the

first title of today's NBA), toyed with names like "Whirlwinds,"

"Unicorns," and "Olympics." While conversing with

the team's PR man, he suddenly hit on "Celtics"

because the name had such a great basketball tradition. Also, Boston

was full of Irishmen; so it could only help ticket sales. Would

the Boston Celtics have

been as successful if they had been the Boston

Unicorns with some other color uniforms (pink for

unicorns?)?

|

John Wooden and Bill Walton

Harv Schmidt

Larry Farmer

Nick Weatherspoon

Tommy Curtis

|

When UCLA Came to the Sugar Bowl

John Wooden's UCLA Bruins had won six NCAA championships in a row when they came to New Orleans in December 1972 to play in the Sugar Bowl Basketball Tournament.

- The 1972-73 edition of the West Coast juggernaut had won their first six games of the season by a minimum of 16 points. That stretched the Bruins' winning streak to 51 games

- The undisputed leader of the Bruins was 6'11" C Bill Walton, who brought an average of 19 points and 17 rebounds into the tournament.

- Harv Schmidt, coach of Illinois, one of the other three participants, said, Walton is one of the best power postmen to ever play the college game.

- Joining Walton in the starting lineup were forwards Keith Wilkes (6'6") and Larry Farmer (6'5") and guards Tommy Curtis (5'10") and Larry Hollyfield (6'5").

- Assistant coach Gary Cunningham, speaking for Coach Wooden, said, The Sugar Bowl has a strong field ... we're looking forward to the competition.

UCLA played Drake in the opening game at the Municipal Auditorium Friday, December 29, with the Illini facing Temple in the nightcap.

- Drake coach Howard Stacey was under no illusion about his team's chances. No doubt UCLA is in a class by itself. ... We are probably a lot like UCLA in philosophy. We'll try full court pressure on defense, and we believe in the fast break offensively.

- His squad entered the contest with a 6-1 mark, including the most recent victory over Iowa 96-80. The lone setback came at the hands of Iowa State 88-84.

- All five Bulldog starters averaged in double figures with 6-2 G David Langston the leader with 18 ppg.

As expected, UCLA jumped out to an early lead before a crowd of over 7,000 that shoe-horned into the 1930-vintage arena.

- The Bruins led 32-24 after 12 minutes of play. But Drake started converting a rash of UCLA turnovers - 16 in the first half alone - into points. The 18-6 run that carried into the second half propelled the Des Moines school into a 38-34 halftime lead and a 42-38 margin in the early minutes of the second half.

- The underdogs benefitted from Coach Stacey's strategy of moving his C, 6'8" Larry Seger, to the top of the key to draw the intimidating Walton out of the middle. Seger canned five buckets on long, looping set shots from 20 to 28'.

- After Wooden made some halftime adjustments, including switching Walton off Seger, the Bruins began firing on all cylinders. Farmer and Walton scored the first 13 points in the second half to build up a 10-point lead.

- The Bulldogs got no closer than eight points after the first five minutes of the half.

- Walton, who led all scorers with 29, simply overpowered Seger underneath. UCLA shot an incredible 63.5% from the floor thanks to numerous layups on the back end of steals and Walton's point blank baskets. (Dunking was prohibited by the NCAA from 1967-76.)

- The final margin was 85-72. At least Drake had the satisfaction of holding the mighty Bruins to their smallest margin of victory so far in the season.

- Stacey was asked what it would take to stop the agile, strong Walton. Another Walton. He is the best center I've seen in a long time, and the best I've every coached against ... including Jerry Lucas. UCLA ... kept the pressure on us and waited for the mistakes even though we stayed with them.

Illinois defeated Temple 82-77 to run their record to 6-2 and earn the right to play UCLA for the championship the Saturday afternoon.

- G Jeff Dawson's 24 points and F Nick Weatherspoon's 22 accounted for over half of the Illini's points. Could the duo continue that production against the Bruins?

- 'Spoon scored 18, but Dawson was held to 14 as the methodical Uclans prevailed 71-64.

- The #1 Bruins didn't have an easy time of it but at no time did they not seem in control of the game. However, they trailed ten minutes deep into the game before pulling ahead 37-31 at intermission.

- Nick Conner, Illinois' cat-quick 6'8" C and a Connie Hawkins look-alike, made Walton work at both ends of the court. After scoring just 10 the first 20 minutes, Bill put in 12 the second half to again lead all scorers and win the MVP award.

- Bruins playmaker Tommy Curtis picked up three fouls in the first ten minutes of action and sat out the rest of the half. UCLA led 37-31 at the break.

- UCLA got its patented fast-break working the second half and built up 53-37 lead in the first six minutes. The Fighting llini lived up to their name but got no closer than the final margin.

- Wooden: I wasn't particularly pleased with our play, but I'm much happier than I was after Friday's game. It was Illinois' pressure which caused our mistakes ... They weren't mistakes of our own. They played a fine pressure defense. Their aggressiveness caused the trouble. ... Conner, as far as I'm concerned, is the most outstanding individual we've played this year.

UCLA finished the 1971-72 season 30-0 for their seventh straight national championship. They would extend their winning streak to 88 before losing to Notre Dame in January, 1973.

|

1972-73 UCLA Bruins after winning their 7th straight national championship

|

CONTENTS

The Path to 24 Seconds - I

The Path to 24 Seconds - II

The Path to 24 Seconds - III

The Path to 24 Seconds - IV

Xavier McDaniel

Luisetti's

One-Handed Shot

Wooden's First National Champs

The

Original Celtics – from New York, not Boston

When UCLA Came to Sugar Bowl

Basketball

Snapshots Index

Basketball

Magazine

Golden Rankings Home |