Pivotal Pro Football Moments

pivotal NFL postseason moment: A decision by a coach or an action by a player that establishes, continues or changes the momentum of a playoff game.

"The Immaculate Reception"

1972 AFC Playoff: Oakland Raiders @ Pittsburgh Steelers

As the #2 and #3 seeds in the AFC playoffs, the 11-3 Steelers and 10-3-1 Raiders met in the first round. The two teams squared off in Week 1 in Pittsburgh. As it turned out, the Steelers' 34-28 victory eventually earned them the right to host the playoff game.

Pittsburgh won all seven of its home games during the season. Their "Steel Curtain" defense allowed just 12 points in their last four games, and they led the NFL with 28 interceptions. Their 175 points allowed was second in the NFL to Miami's 171.

The Raiders were no slouch on defense themselves, ranking fourth in the AFC in points allowed (248). Add in 44° temperature at kickoff with a damp, blustery wind, and you wouldn't expect another 62-point game as happened in Week 1. Still, no one expected the defensive battle that ensued, in which the first half was scoreless, and only 20 points were scored in the second.

Each team had a 1,000y rusher, Franco Harris for the Steelers and Marv Hubbard for Oakland. But neither offensive line could control the line of scrimmage. Consequently, neither side could sustain a running game. Harris gained only 64y on 18 carries, and Hubbard did worse: 44y on 14 carries.

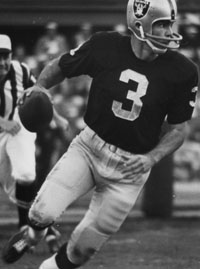

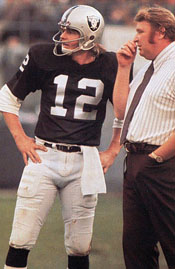

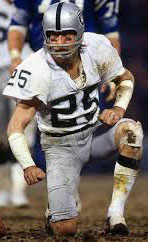

L-R: Daryle Lamonica, Ken Stabler and John Madden, Fred Biletnikoff

Scoreless First Half

Oakland QB Daryle Lamonica did not start the Week 1 game against the Steelers. But when Ken Stabler was ineffective, Lamonica took over and threw two touchdown passes in the fourth quarter. That earned Daryle a start in the next game, and he kept the job for the rest of the regular season.

But the December Steelers treated Lamonica, who was fighting the flu, the same way the September Steelers treated Stabler. The "Steel Curtain" defensive line mounted a strong pass rush and blanketed Daryle's favorite receiver, Fred Biletnikoff, who would catch only three passes for 28y. As a result, the Raiders never got any closer to the Steelers goal line in the first half than the Pitt 44.

Four of Lamonica's passes were smashed back in his face by L.C. Greenwood, "Mean Joe" Greene, Ben McGee, and Dwight White.

Steelers P Bobby Walden helped keep the Raiders deep in their territory. His punts of 59 and 62y were records for AFC playoff games. Eight of Raiders 12 offensive series began inside their 22y line. Until the last minutes of the game, Oakland's deepest penetrations were to the Pitt 47 and 44.

The Steelers mounted a drive in the second quarter that reached the Oakland 32. Coach Chuck Noll decided to go for it on fourth and one, but after the game said he "could've kicked myself" when the play misfired.

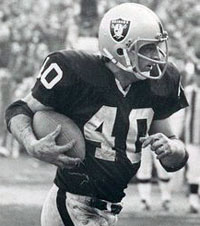

L-R: Roy Gerela, Mike Wagner, Raymond Chester, Pete Banaszak

Steelers Kick Two Field Goals

Pittsburgh's offensive game plan built around running the ball and throwing to the backs finally found some success as they took the second half kickoff and drove 67y to the Oakland 11 to set up Roy Gerella's 18y field goal. Steelers 3 Raiders 0 (9:52)

Oakland Coach John Madden finally called on Stabler to ignite the offense with 11:12 left in the game. But at first he didn't have any more luck than Lamonica.

Pittsburgh drove close enough for Gerella to hit another field goal, this time from the 29. Steelers 6 Raiders 0 (3:42)

With the way their defense was playing, Pittsburgh fans had to feel confident of victory since Oakland's dormant offense now needed a touchdown to win.

Stabler hit TE Raymond Chester for 9y. Then Charlie Smith swept end for a first down. Next came a 12y screen pass to FB Pete Banaszak. The Steelers had done a good job thwarting Biletnikoff, but he got open on the next play for a 12y completion to put the ball on the Pittsburgh 42 – the Raiders' deepest penetration of the afternoon. But that distinction didn't last long as Stabler found WR Mike Siani for another 12y to the 30.

A boring defensive struggle was about to get extremely interesting.

Stabler's Gallop Puts Raiders Ahead

Stabler in his autobiography: "I think what Madden liked best about me was that I stayed relaxed in games, refusing to get rattled, because that was my nature. John, on the other hand, would often go berserk on the sidelines. He would hoot and holler at officials, slobbering at the mouth, pulling at his hair, and waving his big splay-fingered hands all around. All the while his face would get pinker and pinker until we sometimes thought it would bust. Some of the guys called him 'Pinky.'"

Both men's personalities would be on display in the remaining minutes of the game.

Back to pass, Stabler found all his receivers covered. Living up to his nickname "Snake," he slithered outside to escape a hard charge by rookie DE Craig Hanneman and weaved his way into the end zone. S Mike Wagner was the only defender to get a hand on Stabler, who lunged into the end zone near the left pylon. George Blanda's PAT made it Raiders 7 Steelers 6 with just 1:13 on the clock.

Hanneman had just entered the game to replace starting DE Dwight White. "I put an arm out, but he did a reverse pivot. I was outside because we had a safety blitz going, and I closed down. I should have smelled a rat." Hanneman's substitution would have become another "what if?" in football history except for what happened in the remaining 73 seconds of playing time.

Raiders fans, and maybe even Stabler himself, couldn't be blamed for thinking that his amazing 30y run through the vaunted Pittsburgh defense would be forever remembered as one of the most sensational touchdowns in NFL playoff history.

On the Oakland sideline, some Raiders began to think about playing the Miami Dolphins, the defending AFC champions, the following week for a trip to the Super Bowl.

Pittsburgh fans, whose team was playing its first postseason game in its history dating back to 1933, had to be despondent that their team's valiant effort would not be rewarded with a victory. Some must have thought, "Same old Steelers."

The "Immaculate Reception" for the Steelers and the "Immaculate Deception" for the Raiders

Miracles Do Happen

After a touchback, the Raiders deployed their version of the "Prevent Defense." Bradshaw, in his own words, "was just trying to get us close enough for Roy (Gerela) to kick a field goal." He threw to Harris who ran to the 29 and then hit FB John "Frenchy" Fuqua for 11y to the Steeler 40.

Two long desperation bombs to Ron Shanklin and John McMakin were batted away by FS Jack Tatum, and he barely missed an interception on a third aerial. That set up 4th and 10 with 0:26 on the clock.

George Atkinson, Tatum's partner at safety, recalled, "The last thing we said in the huddle is, 'Look, we got this game won. All we got to do is knock the ball down.' And guess what happens ... Tate went for the big knockout."

In the Pittsburgh huddle, Franco Harris thought about "how great a year it had been, and if this was going to be the last play, I was going to play it all the way out. Unfortunately, the play that was called didn't really involve me at all. I was supposed to stay in and block a linebacker if they blitzed, but they didn't."

A change in personnel for the Raiders for the fourth down play sent veteran MLB Dan Conners to the sideline for the first time all day when Oakland was on defense.

On the Pittsburgh sideline, LB Jack Ham could not watch. He began to cut the tape from his wrist with his back turned to the field. RB Rocky Bleier also felt resigned to defeat. He thought, "I can't watch the disaster that's about to take place." DT Joe Greene, ever the optimist, stood next to CB John Rower and told him, "This season has been too good. It ain't gonna end this way."

L-R: Terry Bradshaw, Dan Conners, Jack Ham, Joe Greene

Coach Noll sent in a pass play, "66 Down-In Left," with rookie WR Barry Pearson, who was known for his fine hands. He was the primary receiver on a down-and-in pattern to get a first down, but he was covered on the "in" part of the in-out play. So Bradshaw, who had completed only 10 of 24 passes, resorted to some fancy footwork to escape the clutches of DL Tony Cline and Horace Jones while looking for another receiver. Then he saw Fuqua heading toward the middle of the field. He was assigned to run the "out" route toward the left sideline and away from Tatum. But by the time Bradshaw was ready to throw, Fuqua was heading back toward the middle with Tatum heading toward him.

Tatum had three options. (1) Deflect the pass. (2) Let Fuqua catch the ball and tackle him immediately at the Oakland 35 with only a few seconds left for the Steelers to try a field goal. (3) Live up to his nickname of "The Assassin" and smash Fuqua to cause an incompletion.

Tatum chose the third option. Fuqua leaped for the high pass just as Tatum slammed his shoulder into his upper back. The ball caromed off Tatum, or off Fuqua, or both players and flew back toward the line of scrimmage. Knocked to the ground and woozy, Fuqua looked up and saw Tatum smile wickedly.

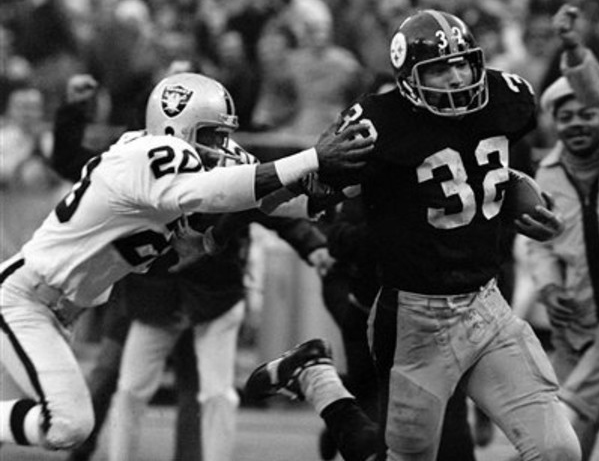

L: Harris catches the ricochet. #31 is Jack Tatum. R: Franco escapes Jimmy Warren.

Several Raiders defenders started to celebrate, thinking the incompletion would give them the ball on downs. On the turf after being hit by DT Tony Cline a split second after he threw the ball, Bradshaw slammed his helmet in disgust. LB Andy Russell on the Steelers sideline recalled, "When the ball was thrown, I watched it thinking that Frenchy might catch it. When I saw the ball deflected backward, I just looked down. I thought the season was over."

Harris had been trained by Penn State coach Joe Paterno to "Go to the ball!" So like Tatum, Franco followed his instinct. "I knew Brad was in serious trouble, so I went downfield in case he needed me as an outlet receiver. I was always taught to go to the ball, so when he threw it, that's what I did. The next thing I knew, the ball was coming right to me."

If Franco had been a half-step slower, the ball would have hit the artificial turf for an incompletion that would have doomed the Steelers. But he reached down and caught the ball at his shoe tops at the Oakland 42. His athleticism allowed him to keep his balance and continue to run instead of falling down. He had been contained all afternoon but now he had running room. Quickly reaching full speed, he sped down the left sideline, pushed away diving S Jimmy Warren at the 10, and went into the end zone with 0:05 on the clock. Back judge Adrian Burk signaled a touchdown, but referee Fred Swearingen did not.

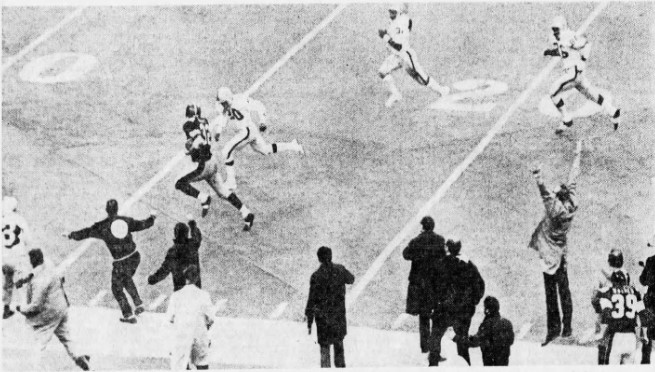

Harris runs to the end zone after fending off Jimmy Warren.

Phil Villapiano, the linebacker assigned to cover Harris, recalled: "I was right with Franco, but after Bradshaw threw the ball, I went over to help out. The ball went over my head to Franco. Had I stayed where I was, it would have been right to me. I saw exactly what happened and made a move to cut Franco off. But McMakin dove on the back of my legs. It was blatant clipping. He always was a smart player, and it was a great play, but he never gets any credit."

The Oakland coaches and players were beside themselves on the sideline. Madden protested that the pass should have been ruled incomplete because it bounced off Fuqua to Harris, and consecutive touches by the passing team was not allowed.

As Steeler fans swarmed onto the field, the officials held up the game while Swearingen went into the baseball dugout at Three Rivers Stadium and telephoned Art McNally, the NFL's supervisor of officials, who was up in the press box. McNally had seen replays of the controversial play and told Swearingen that the touchdown call made by two of the officials was correct. NFL officials later denied it, but many believe it was the first time replay was used to check the outcome of a play. So Swearingen came back onto the field and signaled touchdown.

The Raiders had time for one play, but Stabler's long desperation pass to a receiver surrounded by five Steelers was batted down. FINAL SCORE: STEELERS 13 RAIDERS 7

The only replay footage that appears to show conclusively which player touched the ball to cause the ricochet was the one taken by NBC's end zone camera behind Bradshaw. When it is stopped at the moment the pass hit a player, the ball seems to flatten out on Fuqua's left forearm.

Until his dying day in 2010, Tatum insisted that the ball never touched him. "Frenchy was between me and the ball, so if the ball hit me, it would have had to come through him or over the top of him, and that didn't happen."

Coach Madden years later: "What bothered me about it then and still bothers me now is, if it was a touchdown, why didn't they call it a touchdown right away? If the referee didn't know it was a touchdown when it happened, how did he know it was a touchdown after he went over and talked on the phone? It doesn't go away, so there's never been any closure. I've never gotten over it, and I never will. I have seen guys joke about it, but I never have. Just like that, our whole season, everything we worked for, was over. It's just something you have to live with."

Until his dying day in 2010, Tatum insisted that the ball never touched him. "Frenchy was between me and the ball, so if the ball hit me, it would have had to come through him or over the top of him, and that didn't happen."

Coach Madden years later: "What bothered me about it then and still bothers me now is, if it was a touchdown, why didn't they call it a touchdown right away? If the referee didn't know it was a touchdown when it happened, how did he know it was a touchdown after he went over and talked on the phone? It doesn't go away, so there's never been any closure. I've never gotten over it, and I never will. I have seen guys joke about it, but I never have. Just like that, our whole season, everything we worked for, was over. It's just something you have to live with."

Incredibly, the long-suffering owner of the Steelers, 71-year-old Arthur Rooney Sr., missed his team's touchdown. Win or lose, he went to the Steelers' locker room after every game to greet the players. So he was in an elevator on his way to ground level to console his team on their heartbreaking loss and congratulate them on the best season in the franchise's history. When he got downstairs, he was told of the touchdown but had to wait out the review.

Myron Cope, the color commentator on the Steelers' radio broadcasts, also left his perch in the press box to get ready for his interviews with players after the game. But he went to the sideline rather than the locker room. He recalled, "I was standing near the end zone watching the game wind down. I saw Bradshaw throw the pass, and the ball bounce off I think Frenchy. Suddenly Franco came out of nowhere to catch the ball. He ran down the sidelines straight at me. All of a sudden, I realized what was happening. So I began yelling, 'Come on, Franco. Come on. You can make it.' You can see me on the film replays jumping around and waving my arms to urge Franco on. I'm the little guy in the trench coat with my back turned to the camera. I've watched a lot of games in my time. I saw plenty of big plays. But the Immaculate Reception remains the greatest moment of my career. It's at the top of my list."

Myron Cope, the color commentator on the Steelers' radio broadcasts, also left his perch in the press box to get ready for his interviews with players after the game. But he went to the sideline rather than the locker room. He recalled, "I was standing near the end zone watching the game wind down. I saw Bradshaw throw the pass, and the ball bounce off I think Frenchy. Suddenly Franco came out of nowhere to catch the ball. He ran down the sidelines straight at me. All of a sudden, I realized what was happening. So I began yelling, 'Come on, Franco. Come on. You can make it.' You can see me on the film replays jumping around and waving my arms to urge Franco on. I'm the little guy in the trench coat with my back turned to the camera. I've watched a lot of games in my time. I saw plenty of big plays. But the Immaculate Reception remains the greatest moment of my career. It's at the top of my list."

Not surprisingly, all the talk in the clubhouses was about the winning touchdown.

Coach Noll: "Pearson got hung up, and Frenchy adjusted his route, and Terry went to him. ... Franco had been blocking on the play and then went out. He was hustling ... and all good things happen to those who keep hustling."

Noll added: "Whatever it takes. ... That's the story of this team, isn'it it? Whatever it takes ... even if it's a little luck. One busted play got them a touchdown, why shouldn't it get us one?"

Bradshaw: "The primary receiver was Barry Pearson. He was covered, and I had to do something. I got hit after I threw. When I got up, the next thing I saw was Franco running down the sideline. It looked like his whole army was out of the stands and running beside him. I can't believe it. I've been playing football since second grade, and I haven't seen anything like this." (Harris's fan club was known as "Franco's Italian Army.")

Fuqua: "I saw the pass coming at me, and I thought I could catch it. Then I felt somebody (Tatum) hit me from behind. I thought that ball was too low for anyone to catch. I thought it was impossible to catch. Next thing I knew, Franco was roaring past me, and I wondered what the hell was going on." Asked if Tatum touched the ball, Fuqua replied: "No comment. I'll tell you after the Super Bowl. I'm not chopping down any cherry trees but no comment."

Harris: "I was blocking on that play. After Terry threw the ball, I ran downfield to follow the play. All of a sudden, I saw the ball, and I put my hands out for it. The only thing I could think about was getting to the goal line."

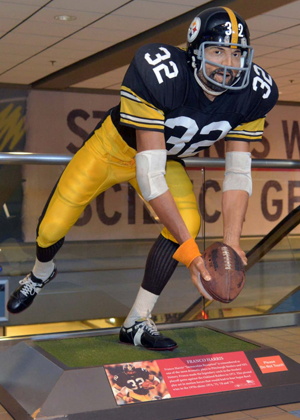

| Fuqua never answered the question of who touched the ball. Owner Art Rooney told him not to tell, saying "Let's keep it immaculate." Raiders LB Phil Villapiano, who was on the field for the play, later said, "I've seen Fuqua several times at golf tournaments or banquets, and we're always dogging him about it (the ricochet). He just laughs and says, 'I'll never tell.'" Harris's catch is immortalized in a statue in the Pittsburgh airport. Dan Connors believes the "Immaculate Deception," as Raiders fans call the play, would not have happened if he were on the field. His reason is that where Harris caught the ball in the middle of the field is the same spot where he would have positioned himself. Another "what if?" to contemplate. |

|

References

Snake, Ken Stabler and Berry Stainback (1986)

Stadium Stories: Oakland Raiders - Colorful Tales of the Silver and Black, Tom LaMarre (2003)

Stadium Stories: Pittsburgh Steelers - Colorful Tales of the Black and Gold, Norm Vargo (2005)

Steel Dynasty: The Team That Changed the NFL, Bill Chastain (2005)

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Heart-Pounding, Jaw-Dropping, and Gut-Wrenching Moments from Oakland Raiders History, Steven Travers (2008)

Their Life's Work: The Brotherhood of the 1970s Pittsburgh Steelers, Then and Now, Gary M. Pomerantz (2013)

Hell with the Lid Off: Inside the Fierce Rivalry between the 1970s Oakland Raiders and Pittsburgh Steelers, Ed Gruver and Jim Campbell (2019)

Snake, Ken Stabler and Berry Stainback (1986)

Stadium Stories: Oakland Raiders - Colorful Tales of the Silver and Black, Tom LaMarre (2003)

Stadium Stories: Pittsburgh Steelers - Colorful Tales of the Black and Gold, Norm Vargo (2005)

Steel Dynasty: The Team That Changed the NFL, Bill Chastain (2005)

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Heart-Pounding, Jaw-Dropping, and Gut-Wrenching Moments from Oakland Raiders History, Steven Travers (2008)

Their Life's Work: The Brotherhood of the 1970s Pittsburgh Steelers, Then and Now, Gary M. Pomerantz (2013)

Hell with the Lid Off: Inside the Fierce Rivalry between the 1970s Oakland Raiders and Pittsburgh Steelers, Ed Gruver and Jim Campbell (2019)