|

Pivotal Pro Football Moments

pivotal NFL postseason moment: A decision by a coach or an action by a player that changes the momentum of a playoff game.

1964: Browns' Superbly Prepared Defense Stifles Colts

1964 NFL Championship Game: Baltimore Colts @ Cleveland Browns

34-year-old Don Shula led the Baltimore Colts to a 12-2 mark in his second year at the helm to win the NFL West Division. Their opponent in the championship game was the Cleveland Browns, the team Shula played for in 1951-52 when the current Browns coach Blanton Collier was an assistant on Paul Brown's staff.

The Colts led the league in points allowed, 16.1 per game. Four veterans from the 1958-59 champs continued to lead the defense: LE Gino Marchetti, talked out of retirement for one more year, RE Ordell Braase, RLB Don Shinnick, and MLB Bill Pellington, age 37 like Marchetti, which made them three years older than their head coach.

The Browns defied the conventional wisdom that defense wins championships. They finished dead last in yards allowed (4,722) and gave up 20 more first downs than any other team. But they were fifth in points allowed (293), showing their "bend but not break" resiliency.

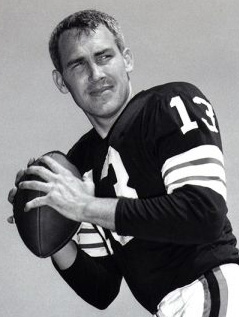

L-R: Don Shula and Johnny Unitas, Blanton Collier, Frank Ryan Collier Studies the Colts for Two Weeks

With no playoff needed to determine either conference champion, the teams had two weeks to prepare for the big clash. That provided Blanton Collier with a delicious opportunity since he basically invented film analysis when he served on Paul Brown's staff from 1946-53. As Terry Pluto put it, "You give Blanton Collier a film projector, a quart of ice cream, and some time, and he'll come up with a Picasso of a game plan."

The coaches exchanged five game films. That provided Collier with a gold mine of footage to compile a dossier on every Colt on each side of the ball. Players like secondary captain Bernie Parrish came to Blanton's house and watched with him as he dissected the Baltimore passing attack. Other Browns watched films of their opponent on their own until they got to know their every tendency.

The more Collier watched the Colts, the more he thought his Browns could beat them. He also knew that, with the right game plan, his quarterback, Frank Ryan, could outplay Colts QB Johnny Unitas.

Individual Browns were given instructions on how to handle their Baltimore counterparts.

RT Monte Clark was told to ignore DE Gino Marchetti's head-and-shoulders fake and slap to the helmet. Just stand there. Get in his way.

On the other end of the line, T Dick Schafrath was told that DE Ordell Braase, being left-handed, almost always went left. Ignore his head fake to the right. Like Gino, Ordell liked the head slap. Schafrath was told to counter that move with a punch under Braase's chest pad.

The more they watched film, the more the Browns offense felt they could score on the Colts. The only way to cover outstanding receivers Paul Warfield and Gary Collins was to double-team them. But they couldn't double cover both. Also, no team possessed a weapon like Jim Brown. Ryan even told reporters eleven days before the game, "We have more offense than the Colts."

DT Dick Modzelewski, a 12-year veteran who came to the Browns that season from the Giants, had faced G Alex Sandusky many times. So Mo tutored the other defensive tackle, second-year pro Jim Kanicki, in ways to handle giant OT Jim Parker, 6'4" 275 lb.

Collier told both Modzelewski and Kanicki to play the run–just hold your ground. It would fall to ends Paul Wiggin and Bill Glass to put pressure on Unitas.

The main defensive plan Collier concocted involved the coverage of Unitas's receivers. He and Parrish noticed that opponents played off Raymond Berry and Jimmy Orr, afraid of getting beat deep. That allowed Unitas to throw his precisely timed down-and-outs and slant-ins. Parrish wanted to get right up on the receivers to bump them and mess up the timing.

LB Walter Beach, assigned to cover Berry, noticed in the films that, while the great Colt receiver faked with his head, shoulders, and feet, he could not fake with his waist. Confident he was quicker and stronger than Berry, Beach was ready to cover him tight.

The Colts entered the clash as seven-point favorites. The press almost universally predicted the Colts would win. Many even predicted a rout. Ed Shrake wrote in Sports Illustrated: "It is yawningly conceded that the Eastern Conference champion Cleveland will be playing merely for the dubious pleasure of being thrashed by Baltimore on December 27. There are at least three teams in the West that are superior to any in the East. To be realistic about it, the championship game of 1964 has already been played. Baltimore won it in October by beating Green Bay for the second time."

Football historian Ernie Accorsi, who would later serve as general manager of both the Colts and Browns, recalled: "No one, and I mean no one, outside of Cleveland gave the Browns a chance. The prevailing thought was that Unitas would score so many points that Cleveland would not be able to keep up. They would nullify Jim Brown."

However, Collier had the utmost confidence. Two days before the game, he told Cleveland writer Hal Lebovitz, "Hal, we have covered everything. We are prepared. We are going to win." Knowing how unusual it was for a coach to express such optimism, Hal sensed that something special might happen on Sunday.

Cleveland Municipal Stadium during the 1964 Championship Game Light snow flurries fell off and on during the game.

The teams' defensive preparation paid off as the first half ended scoreless. The Browns "clamping" coverage had an impact immediately. Colts radio announcer Frank Messer observed that Unitas was "running more today than he has all season."

The Colts got close enough to try a field goal early in the second quarter but a botched snap turned the ball over. The high-scoring game many predicted was not transpiring. The Colts left the field at halftime stunned.

In the Cleveland locker room, Collier was surprised that he didn't have to make any defensive adjustments. So he asked for suggestions from his offense. "They're stacking it up pretty well inside," said Brown. "It might be time to throw the ball more." With the Colts double-teaming Warfield, Collins said all there was between him and the goal line was little Bob Boyd, five inches shorter, and he could beat him any time he wanted.

Collier Takes the Wind in Third Quarter

Collier made a decision at halftime that would have a big impact on the game. "Most of the time you want the wind with you at the end of the game so you can rally if you have to. But I decided maybe we better take the wind while it was still blowing. If we gave it to the Colts and they got hot, we might be out of the game by the time we got it in the fourth."

If the Colts made any offensive adjustments at halftime, they didn't work. After a three-and-out, Tom Gilburg's punt into the wind traveled only 25y to the Baltimore 48.

A second down screen pass to Brown moved the ball to the 38 for a first down. But a short run and two incompletions by Ryan under pressure brought out 41-year-old Lou Groza, who boomed a 42y field goal. Browns 3 Colts 0 (11:39)

Brown Breaks Loose

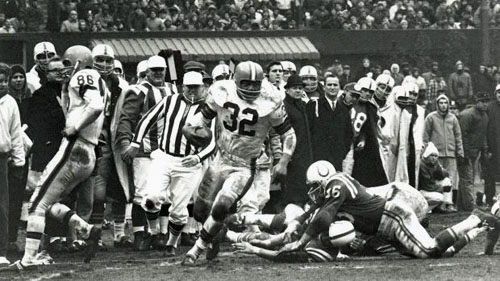

The Browns quickly forced another punt and started another scoring possession, this one from their 31. After Brown took a draw handoff for five, the Browns lined up in a double wing, with HB Ernie Green as a flanker to the left. The only man behind Ryan was Brown. RLB Don Shinnick cheated a little toward the middle. The defensive back opposite Green played 6-7y behind the line. Ryan tossed a quick pitchout to Brown swinging to his left. He swept around the pinched-in linebacker as Green knocked down DE Ordell Braase. Jim ran behind three blockers all the way to the Colt 18 where DB Jerry Logan made a touchdown-saving tackle from behind. Green got up from his first block and raced downfield where he took out MLB Bill Pellington to help the 46y gain.

Jim Brown breaks loose down the sideline. Collier: "We didn't use that sweep much in the first half. Maybe we were thinking too much. It had gained a lot of yards for us during the season, and we knew the Colts knew it. So we didn't go to it in the first half. It was very effective in the second half."

Ryan: "They were playing the corner way off the line. Most clubs play the cornerback up close when we come out in the double wing, figuring he can cross the line and force Jim Brown back and wide on the sweep until help gets there. But they were playing him deep, and when Jim turned the corner, he was home free."

Green: "That play really got us going. We finally broke Jim loose, and we knew we were going to be all right."

Ryan took the next snap, stepped up in the pocket, and found Collins open in the end zone behind the goal posts after he got away from Boyd and Logan. Browns 10 Colts 0 (13:34)

Collins had noticed that Boyd was shading him toward the sidelines. So he broke the other way, heading for the goal post. Ryan had enough time to read the change and let fly. Five times that year he had hit a goal post. But this time, the ball went under the crossbar.

The Colts' woes continued when Tony Lorick made a bad decision to run the kickoff out from 1y into the end zone. He made it only to the 12, and a clipping penalty moved the ball back to the six. After a 2y run, Unitas tried to pass but yet again ended up running, for just a yard. He threw a short pass to Lorick who was felled at the 12. Gilberg wasn't so lucky on his punt this time, the ball going out 27y upfield to the Colt 39.

Ryan Calls "Hook & Go"

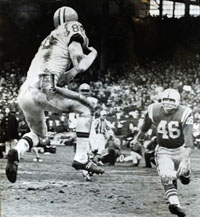

Smelling blood, Ryan called a play known as "Hook & Go." Collins faked the hook to freeze the defensive back, then ran straight for the end zone. Jim lofted a high spiral with the wind toward Collins. Boyd slipped down on the dirt infield, and all Gary had to do was cradle the ball on the five and waltz into the end zone. Browns 17 Colts 0 (6:12)

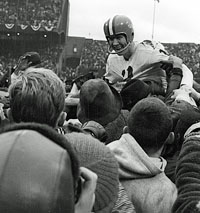

L: Gary Collins snags TD pass. R: Ryan carried off the field. Ryan: "This was probably the most important decision I had to make all afternoon. We had established tremendous momentum. The running was going; we had just gained 46y on a running play, and I was tempted to call another sweep. But maybe I would call a sweep into an outside blitz, and they would drop Jim for a long loss. Then I thought maybe we can go inside, but if they pinched in and cut off the inside we wouldn't gain, and the momentum could go from us to them. I knew they had been playing Gary Collins for a hook pass all afternoon. I decided to call a hook-and-go to Collins, and when he went he was open.

"Gary was so wide open, I had buck fever," said Ryan. "There was no one within 20 yards of him. I had the wind at my back. It surprises you when a receiver is that wide open, but it happens occasionally. I just had to make sure I got him the ball, because Gary could have caught it and walked into the end zone."

Collins: "When I faked, Bobby Boyd slipped and fell. When that ball was in the air, I kept thinking that if I dropped it, I had better catch a jet out of Cleveland right now."

Boyd: "We couldn't hear our calls. We blew one on that play, and we blew another one later. The guy who was supposed to take the middle deep took the outside."

The game was essentially over. The only question was whether the Colts would score. The answer was a resounding "No!"

Cleveland added ten more points in the fourth quarter on a second Groza field goal and another Ryan-to-Collins connection, this one covering 49y.

Final score: Browns 27 Colts 0

References:

Run It! And Let's Get the Hell Out of Here!" The 100 Best Plays in Pro Football History, Jonathan Rand (2007) |