|

Pivotal Pro Football Moments

pivotal NFL postseason moment: A decision by a coach or an action by a player that changes the momentum of a playoff game.

1958: Greatest Drives Ever

NFL Championship Game: Baltimore Colts @ New York Giants

Leading 17-14 late in the fourth quarter, the Giants face 3rd-and-four at their 40 at Yankee Stadium. Frank Gifford takes a handoff and starts right behind two pulling guards. DE Gino Marchetti slips E Bob Schnelker's block and tackles Frank near the 44 just before Gene "Big Daddy" Lipscomb comes barreling in. Everyone in the pile gets up except Gino who stays prone with what turns out to be a broken right ankle.

Marchetti: "I was able to slip my blocker and get out into the flow. Gifford ran right and I tackled him. To make sure Frank didn't go any further, Big Daddy hit the whole pile. He just wasn't going to let anybody or anything get to the 44y line. Daddy, not Gifford, was the one who broke my ankle."

After a few minutes, Marchetti is carried off on a stretcher. Then the officials measure for the first down and find the ball a foot short. The Giants strongly protest the spotting of the ball.

Gifford recalled: "A runner knows when he makes a first down. It was close, but there's never been any doubt in my mind that I made that one. In all the confusion around Gino's injury, the refs blew the spot. Then, even though we only had about a foot to go for the first down, I think the decision to punt was the right one."

With the injured Colt lying right where the play ended, referee Ron Gibbs picked up the ball and held it until Marchetti was carted off. When he put the ball back down, he put it near his back foot instead of his front foot. For the 2008 program "The Greatest Game Ever Played," ESPN hired an analyst to study the available footage of the play and use 21st-century computer techniques to determine whether Gifford made the first down based on where he landed when tackled. Conclusion: He was short by nine inches. Giants offensive coach Vince Lombardi urges head coach Jim Lee Howell to go for it and defensive coach Tom Landry agrees, but the head coach elects to punt. The Colts receive Don Chandler's kick on a fair catch at the 14. QB Johnny Unitas and the offense take the field with 2:20 on the clock.

Colts E Raymond Berry recalled: "I said to myself, 'Well, we've blown this ballgame.' The goalpost looked a million miles away."

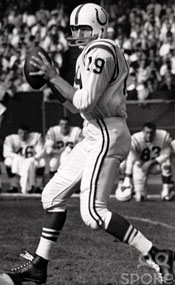

Unitas: "Our coach (Weeb Ewbank) never called the plays. He turned the game plan over to me. The guys up in the press box, they would ask me, 'What do you want to know?' I said, 'If you can find any kind of a tendency on them as far as their rushing linebackers, let me know. Otherwise, just sit there and enjoy the game.' Once in a while, Weeb would send things in to me like, 'Tell John to make the first down,' or 'Tell John we gotta score a touchdown here,' but that was fine with me. The decision was mine.'    L-R; Frank Gifford, Gino Marchetti, Gene Lipscomb Thus began what is arguably the most famous drive in NFL history.

Play 1: Calling two plays at a time, Colts QB Johnny Unitas passes incomplete to TE Jim Mutscheller, who was double covered as he ran down the hash marks. Two minute warning. Play 2: Incompletion on an underthrown pass to HB L. G. Dupre. Play 3: Unitas finds HB Lenny Moore, who went down 12y and turned back, for a first down at the 25. Play 4: Another underthrown pass to Dupre. Play 5: Unitas to Berry on a slant-in, and Ray runs through several arm tackles for 25y to midfield. Timeout with 1:05 showing. During the timeout, Landry takes the double team off Moore and puts it on Berry. Early in their relentless off-season practice sessions, Unitas asked Berry what he would do if a linebacker moved out to cover the L-pattern or square-in. Raymond replied, "I guess I'd give him an outside fake like this, try to make him come after me, then jump underneath him like this." Neither mentioned the strategy again until the Colts broke the huddle on Play 5 of the drive, and Harland Svare moved in front of Berry. Ray glanced at Unitas, who smiled. "John had called a ten-yard square-in for me. I went to the line, and there was Svare. I'll never forget the look John gave me, the look that we gave each other. I made that fake I had described to Unitas two years earlier, and Svare came right after me. I jumped underneath him, and John zipped it on a perfect line about seven yards down the field. I ran for the rest of the first down."

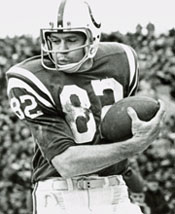

L-R: Johnny Unitas, Raymond Berry, L. G. Dupre, Lenny Moore L-R: Johnny Unitas, Raymond Berry, L. G. Dupre, Lenny MoorePlay 6: Knowing the defense was expecting sideline passes that would allow the receiver to step out and stop the clock, what Landry called "prevent mode," Unitas fakes a pitchout and hits Berry over the middle again for 15 to the NY 35. Baltimore takes its last timeout with 0:43 left.

Giants MLB Sam Huff: "Unitas threw that ball right by my ear. I was in the right place, but I couldn't get my arm up in time. It whooshed past the ear hole of my helmet. I go to bed every night hearing, 'Unitas to Berry,' 'Unitas to Berry,' said Sam, imitating famed Yankee Stadium PA announcer Bob Sheppard. "His voice echoed in my head."

Play 7: Unitas to Berry who bends down like an infielder to take the low throw inches off the ground, turns, breaks a tackle, and runs for 22y to the 13.

Berry: "There was just enough time for the kicking team to come on and tie it. ... Decades later, I asked John, 'Why, all of a sudden, did you come to me three times in a row?' ... He smiled and said, 'Because I figured you'd catch them, Raymond.' John wasn't overly analytical. He was instinctive. You know, when something like that is going on around you, you miss a lot of it. You don't grasp it all. Because we didn't have time to huddle, the Giants were also operating without perfect communication. So all of us were in a different rhythm. The game had kind of moved inside our heads. That's the two-minute drill in spades. Maybe the whole deal came down just to how well John and I knew each other."

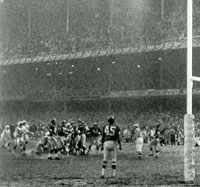

Landry: "We were looking for a pass and went into a special defense. Both linebackers, (Harlan) Svare and (Cliff) Livingston, were over on the strong side to double up on Moore. (Jimmy) Patton and (Carl) Karilivacz doubled Berry. Huff played pass, and they caught us." Play 8: With no time to think and feel the pressure, K Steve Myhra rushes in with the field goal unit and, without a huddle, kicks a 20y field goal. Colts 17 Giants 17 (0:10)

L: Unitas passes to Berry in front of Karilivacz C: Myhra's tying field goal sails through the uprights. R: Giants win the overtime coin flip. Backup QB George Shaw served as Myhra's holder. As he left the sideline, LB Dick Syzmanski told him, "For crissakes, George, don't fumble the ball." So Shaw kept repeating to himself, "Don't drop the ball, don't drop the ball." "It felt like a hunk of ice," he said afterwards. Years later, George admitted, "I've woken up since then in the middle of the night, thinking, 'Don't drop the ball.'"

On the first play after the kickoff, the Giants ran a quarterback sneak to run out the clock.

L-R: Charlie Conerly, Bill Pellington, Sam Huff Many of the players on both sides thought the game had ended in a tie and that the teams would split the proceeds fifty-fifty. The New York captains, Bill Svoboda and Tobin Rote, had no idea what to do until an official came over to lead them to midfield for the coin toss.

In 1941, the NFL passed a rule that had never been applied for 17 years. If a playoff game ended in a tie, the teams would play a sudden-death overtime. On the NBC TV broadcast, Colts announcer Chuck Thompson told the audience: "Something historic that will be remembered forever is happening today, ladies and gentlemen."

The Giants' 37-year-old QB Charlie Conerly had been voted the game's Most Valuable Player by the sportswriter late in the fourth quarter. Already exhausted by the grueling contest, he could barely drag himself onto the field for the overtime. Charlie told his good friend Gifford, "I just can't go on anymore." Frank told him, "Boy, you're going to have to go some more." "I can't," replied the exhausted quarterback. With Marchetti unavailable, Unitas represented the Colts for the coin toss. As the visiting captain, John called "tails" but lost and kicked the dirt, fearful that his offense might never get the ball if the Giants scored on their first possession. The Colts chose to go kick toward the same goal as in the fourth quarter, the one in front of the outfield bleachers where most of the Colts fans were located.

The Giants desperately need to score on their possession and win the game to keep their spent and frustrated defenders off the field. Bert Rechichar kicks to Don Maynard, who loses the ball in the lights. He fumbles, recovers, and returns 10y to the 20. Rookie Johnny Sample replaces the injured Milt Davis at cornerback, but the Giants don't seem to notice. They run Gifford for four. Then Conerly throws an incompletion low and outside to Schnelker. On third down, Charlie rolls right and tries to run for the first down, but MLB Bill Pellington pulls him down 2' short. This time, no one argues against Howell's sending in Chandler. Taseff returns the 52y punt to the Colt 20.

Alan Ameche: "John told us, 'We're going to go right down the field and score.' No doubt about it. You could just feel the confidence."

Now came the second most memorable drive in NFL history.

Play 1: With Huff helping Karilivacz on the right side with Berry, Dupre starts wide and cuts back over right tackle for 11 to the 31. Play 2: Moore races down the right sideline, but Lindon Crow stays with him and breaks up John's long pass. Play 3: Dupre for 2 to set up 3rd-and-8. Play 4: Seeing Huff and Karilivacz drop into coverage early as LE Berry heads downfield, Unitas tosses a flare pass in the left flat to Ameche, who runs for eight and a first down on the 41. Berry: "Ameche lined up in the backfield. I was split out. His route was a wide flair. I was running a hook pattern, and Svare was trying to help Karilivacz with me, instead of covering Ameche. ... To catch the pass that John threw Alan, you couldn't have just ordinary hands. Ameche made the first down by less than a yard."

Play 5: Dupre again runs behind the right side of his line and gains four.

Play 6: DT Dick Modzelewski beats G Alex Sandusky, shoots in, and sacks Unitas for a loss of eight. Play 7: On 3rd-and-14 from the 37, Unitas wants to throw to his right but, with no one open, escapes the rush to his left and passes to Berry, who comes back to the ball and gains 21 to the NY 42. Berry: "3rd-and-14. Here's where attention to detail paid off. John scrambled left, and I ran a route we called 'come open late.' I was the third choice on this play. I cut a stutter-step pattern straight into that muddy spot that I had found before the game. Behind me, Karilivacz slipped and fell right on his butt. I didn't see him go down - I was already turned toward John - or we would have had a touchdown. Unitas flapped that big left hand at me, signaling 'Take off!' But I didn't react quickly enough. So he just drilled me in the hands. First down in Giants territory."

Play 8: Unitas calls an audible at the line, a trap play for Ameche who takes the ball just before Modzelewski arrives and bursts 23y to the 19, where Patton drags him down.

Some of the players regard the trap play as Unitas's best call of the game.

Berry: "Our audible system consisted of colors. Red was the live color. So, when Unitas came to the line of scrimmage, he'd go, 'Blue 81! Blue 81! Set! Hut!' But this was a red call, a two-hole trap. Sam Huff had started cheating to the left, trying to help out on all these quick passes. ... If I hadn't loafed on the play, Ameche might've scored. My job was to get to the safety, and my excuse was that I was dragging and worn out. That play never breaks for more than two or three yards, anyway." Unitas: "Sam kept dropping back a little more, a little more. Also, Modzelewski had just sacked me two plays before. I figured he'd be pumped up and trappable. If Art Spinney could trap Modzelewski, and Buzz Nutter could cut back on Spinney's man ... then all George Preas had to do was shield Huff a little - he didn't even have to block him - and Ameche could shoot through. There wasn't anything magical about it. I didn't pull it out of a hat. The defense told me what to do. It's what you worked on all year, when you practice the two-minute drill." Play 9: The Giants finally guess right and stop Dupre for no gain at right tackle.

Play 10: Unitas hits Berry on a slant-in. Leaning forward to make the grab, Ray falls on the 10 but lunges to the eight before being covered. 1st and goal. Play 11: Ameche gains a yard. The game is stopped while a well-dressed drunk runs onto the field. He was actually an NBC employee who was stalling so that a dislodged cable could be reconnected to restore the live picture to black and white screens across America.

During the interruption, Unitas comes to the bench to see what head coach Weeb Ewbank has in mind for the next play. "Well, Ameche's a fine ball carrier, says the coach, who seems content to run the ball, then kick the field goal. Weeb recalled, "Unitas didn't say a word when I mentioned Ameche. He just stood there starting at me, like he couldn't quite remember who I was." Play 12: With the nation watching again, Unitas makes his most daring call. He drops back, freezes Crow with a pump-fake to Moore going into the end zone, then lofts the ball to Mutscheller who twists to catch the ball on the two. His momentum carries him out of bounds just outside the pylon.

Ewbank: "He (Unitas) came up with that pass. I almost fainted on that one."

Unitas: "The strong-side linebacker (Livingston) took an inside position on Mutscheller, which surprised me. ... You'd expect him to play Jimmy straight up, if not a little on the outside. The defensive back, Lindon Crow, was well into the end zone. And I knew Crow had to worry about Lenny Moore coming out of the backfield. Really, they were the only two defenders in the picture. ... So Jimmy was open on a diagonal from the very first step he took. People said it was a gamble, but they couldn't see what I was seeing. If Jimmy had been able to keep his footing on the icy sideline - his momentum basically slid him out of bounds - he would have walked into the end zone ... I actually overthrew him a little. It was my fault that it wasn't a touchdown." When asked by a reporter afterward why he risked an interception when a short field goal could end the game, Johnny replied, "When you know what you are doing, you're not intercepted. The Giants were jammed up at the line and not expecting a pass. If Jim had been covered, I'd have thrown the pass out of bounds. It's just that I would rather win a game like this by a touchdown than a field goal." Years later, a Baltimore writer asked Unitas the same question. John just laughed. "Hell," he said, "if Mutscheller wasn't open, I'd have thrown it away. Once you've figured out what's the right thing to do, all you need then is the nerve to do it. I've always liked touchdowns better than field goals ... Nothing against Myhra, but I had more confidence in me." Mutscheller: "The play was called for Alan. But when John checked off, I didn't think a thing of it. He was always pulling out plays we hadn't run since training camp. If he thought this would work, so did I. You could tell from his confidence that he was going to make it work. Everyone in the huddle got confidence from him. ... John never stopped telling me, 'Geez, Jim, I tried to make you the hero.' But then, if I had scored that touchdown, Ameche wouldn't have been able to sell all those hamburgers (at his restaurant chain)." Play 13: Huff said, "We all knew the next play was going to be a run, and that Ameche would be carrying, but it didn't do much good." Against a stacked front expecting a run to the Colts left side with Huff in a three-point stance, Ameche puts his head down and careens untouched through a big hole at right guard into the end zone with 6:45 left in the extra period.

FINAL SCORE: Colts 23 Giants 17   Ameche scores! The writers revoted and chose Unitas to receive the Chevrolet Corvette that went to the Most Valuable Player. |