|

Wallace Wade, an assistant coach at Vanderbilt, took over the Alabama football program in 1923 and immediately raised it to new heights. His second Crimson Tide team won the Southern Conference Championship with a 5-0 league mark and 8-1 overall. His second squad defended its Southern title by winning all nine of its games to become Alabama's first undefeated team in its 24-year football history. Bama allowed only seven points all season.

Oddly enough, it was Birmingham-Southern–one of the Tide's weakest opponents–that scored the touchdown, driving just 25y after recovering a fumble.

The two stars of Alabama's team were both backs who would earn admittence to the College Football Hall of Fame. 5'11" 160lb HB Johnny Mack Brown earned the nickname the "Dothan Antelope." Stanford coach Glenn "Pop" Warner called Johnny "one of the fastest football players I've ever seen."

Brown had a terrible memory, which caused Wade to institute a huddle so that Johnny had to remember only one play at a time.

Allison "Pooley" Hubert, a 5'10" 190lb senior, played both fullback and quarterback ("quarterback" being the blocking back in the single-wing system that was popular at the time). He came to Alabama as a 21-year-old freshman after serving in World War I. "Papa," as his teammates tagged him, was outstanding on both sides of the ball, scoring three or more touchdowns in six different games during his career and ranking as one the best defensive backs in the country. As a result, he was voted the Most Valuable Player in the Southern Conference. Pooley played without a helmet.

Hubert was born into a Catholic family in Meridian MS 95 miles from Tuscaloosa. He was probably the only member of that faith on the Alabama roster.

An Alabama graduate, Champ Pickens, was a big booster for his alma mater whose name was on the cup awarded annually to the Southern Conference champion. He told author John McCallum how he lobbied the Rose Bowl to pick Alabama.

Jack Benefield, the Pacific Coast Conference representative, was sent to the East Coast to search for a suitable opponent for the Washington Huskies. Benefield's first choice was Tulane, and he personally offered the invitation to Coach Clark Shaughnessy at a meeting in Chicago. But Shaughnessy couldn't get Tulane president Dr. A. B. Dinwiddie to okay the offer. So Clark suggested to Benefield that the Rose Bowl committee invite Alabama. Benefield was cool to the proposal. He said he had never heard of Alabama as a football team. By gum, he couldn't take a chance on mixing a lemon with a rose. But, to his credit, Benefield said he would check Alabama out, and Shaughnessy went to a phone and called Wade and tipped him off that he was sending Benefield to Tuscaloosa to talk Rose Bowl with him.

Washington's "Wonder Team,"

which led the nation in scoring, was quickly installed as a 2-1 favorite over the little-known Tide. Southern football was nationally rated as inferior to the game played in the East, Midwest, and West Coast. The general regard for Alabama's chances was summed up by syndicated newspaper columnist Will Rogers when he referred to Alabama as "a team from Tuska-loser." But Alabama's starters had played together for three years and would not be intimidated by the biggest stage in college football at that time. Also, as a California writer put it, "Washington is about as welcome as the plague in this part of the country. All of Southern California was pulling for Alabama ..."

But Alabama had a standing rule against postseason games. Dr. George Denny, the university president, and Wade never saw eye to eye on some things, especially what Wade's salary should be, but they most certainly agreed on the subject of football: it was vital to the future growth of the University of Alabama. The rule against postseason games was rescinded. As Alabama's number-one promoter ... I also played a role in the situation by getting Governor Bill Brandon to sign a telegram I was sending to the Rose Bowl committee. Without even asking me for an explanation, the governor said, "Go right ahead, Champ." I said, "Don't you want to know what it says?" And he said, "Forget the details. Good luck." So I phoned Western Union and dictated this message: "Speaking unofficially and without knowledge of University of Alabama authorities, I the governor of Alabama want to call to your attention the Crimson Tide's great football record this season. If you are interested in a real opponent for Washington in the Rose Bowl New Year's Day, then give Alabama serious consideration." The chairman of the Rose Bowl committee wired back: "Governor Brandon - Thank you for your wire; be assured we will give Alabama utmost consideration." Two weeks afterward, the Tide received an official invitation. Suddenly the cry all over Alabama was "California, here we come." It seems that Southern California went to Washington for a game in 1923 with the promise of a return engagement in Los Angeles the next season. But after beating the Trojans 22-0, UW backed out of the second game.

The Alabama delegation traveled to Los Angeles by train, the journey taking four days and nights. They arrived December 24 and were immediately the Toast of the Town. They hobnobbed with movie stars, were taken to dinner by transplanted Southerners, and toured the sites until Wade shut it all down. He conducted hard, closed practice sessions.The West Coast press continued to provide motivation fuel. One writer predicted Washington would win by 51 points. Another said the Huskies would "blow the country team back across the continent." Pickens recalled: Some of our players never before had been away from home. Pasadena seemed to them like another planet. They were nervous, homesick. I made some calls to Tuscaloosa and instructed the folks to start a barrage of telegrams to our locker room. "Remind our kids that now is their chance to get even with the damn yankees." That Civil War pitch will do it every time. So in response to my last-minute pleas, 'Bama fans burned up the telegraph lines. Just before rushing out on the field to do battle, our kids gathered in a large semicircle around Coach Wade and heard the messages. There was not a dry eye in the room. The sentiment was pretty well summed up by the war whoop of one of our big linemen: "Let me at 'em! I'll murder those [expletive deleted] murderers!"

Crowd of 50,000 at the 1926 Rose Bowl The entire Deep South was united behind the Crimson Tide. With radio in its infancy, the 1926 Rose Bowl was broadcast only in Los Angeles. However, the Associated Press broadcasting station in Atlanta transmitted the game play by play as it was received from Pasadena. So fans gathered in the homes of fortunate owners of "radio receiving sets" in cities across the Deep South from Baton Rouge to Atlanta.

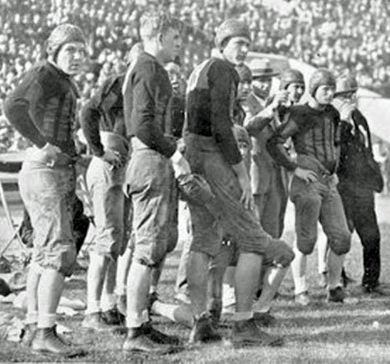

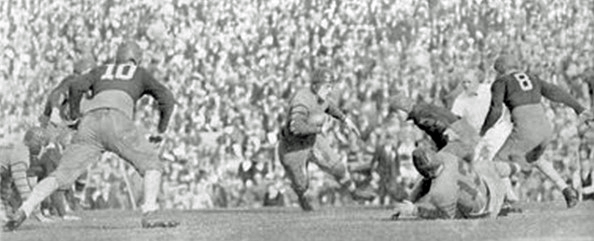

The game was a Tale of Two Halves, with a rough tackle by Washington's All-American HB George "Wildcat" Wilson and then his departure with an injury helping the "plucky" Tide turn the tide after intermission.In Montgomery, fans packed the Grand Theater where a large gridiron had been mounted to the stage. As play by play reports came in, a football was moved on the display Perhaps the Southerners were too fired up or maybe they were intimidated by the crowd of 50,000. In any case, the Purple Tornado built a 12-0 first-half lead. First Quarter Receiving the kickoff, Bama drove to the UW 15 with Johnny Mack Brown's 15y sweep and Pooley Hubert's 29y pass to Grant Gillis the big gainers. But the Tide went backwards from there, and George Wilson intercepted a desperate fourth-down pass and ran it out to the 15. Washington marched from there to a touchdown. Wilson's 11y run over right tackle gained a first down. The Huskies went for it on 4th-and-5 from their 45. Wildcat connected with QB George Guttormsen who went out of bounds on the Alabama 15. Three snaps later, George crashed around left end to the 1' line, warding off three potential tacklers along the way. Harold Patton, the other halfback, was given the honor of carrying the ball over the goal line. However, Guttormsen missed the drop-kick for the extra point.   L: Johnny Mack Brown runs against the Huskies. R: Bama sideline.  George Wilson carries for Washington as Pooley Hubert (10) zeroes in on him. Wilson also made possible Washington's second touchdown. First, he boomed a punt 65y into the Bama end zone. On the ensuing series, Wilson tackled Brown and twisted Johnny's leg violently. The enraged Crimson Tide vowed to get revenge. When Gillis punted back four plays later, the Huskies started from their 42. Wilson ripped off a 33y gain to the 22. Then the All-American hurled a pass to E John Cole in the back corner of the end zone. Guttormsen's drop kick for the PAT hit the crossbar - a second failure that would doom the Huskies. 12-0 UW. Washington again received the kickoff but moved to three first downs. Then Wilson tried to turn left end but was smashed by the Tide and had to be taken off the field with injured ribs. A 15y holding penalty thwarted the advance, forcing a punt that Brown ran back 40y to the UW 46. Hubert connected with Brown for 14y as the quarter ended.  Brown tackled as E Emile Barnes (right) looks for a block. As the crowd at the Grand Theater in Montgomery went outside during the halftime break, you couldn't blame them for thinking, "Maybe our boys aren't as good as we thought."

Third QuarterThe story goes that Wade went into the Bama locker room at halftime and told his team, "And they told me Southern boys would fight." Then he left. Later during the halftime, Brown was spotted sitting in the stands with his shoes off. Wade decided to change his offensive strategy to utilize Brown's pass catching ability. With Wilson still out of action the entire third period, the Tide scored on three straight possessions. After a punt exchange, Hubert, "the seasoned and mature team leader," kept calling his own number after the Tide gained possession on the UW 41. Pooley scampered 26y to the 15. Then he tore off ten more before bucking the last five to put the Tide on the board. Bill Buckler kicked the PAT to cut the deficit to 12-7.   L: Pooley Hubert breaks off a 17y run. R: Hubert scores. Bama kicked off and soon had the ball back. On the second play, Grant Gillis heaved a 45y pass that Brown took in stride "like Tris Speaker catching a fly ball" (to quote one reporter) and sprinted the remaining 20y to pay dirt. Buckler again converted and just like that, Alabama led for the first time, 14-12.

Louis Tesreau, playing in place of Wilson, fumbled, and Alabama recovered at the 30. Hubert, smelling blood, immediately called an audacious play. He dropped back and lofted the ball downfield. Brown grabbed it on the five and zipped over. Buckler missed the point, but with the two-point conversion 34 years in the future, the Tide still had a two-score lead, 20-12. Brown explained the third touchdown: "Pooley told me to run upfield as fast as I could. When I reached the three yard line, I looked back and, sure enough, the ball was coming over my shoulder. I took it in stride and went over carrying somebody. The place was really in an uproar."

The Wilson-less Huskies couldn't make a first down before the period mercifully ended for them.Fourth Quarter Four plays in, Wilson returned to the field with Bama on UW's 32. A few plays later, Hubert failed by an inch to make a first down at the 12. Then he misfired on a fourth down pass. "Wildcat" then led an 88y touchdown drive. He started with an 18y sweep around left end. Patton followed with a 20y gallop around the other side. Three plays later, George passed to Guttormsen for to move the chains to the UA 31. After a 4y run, Wilson fired "a long low pass" to Guttormsen for a touchdown. Eugene Cook booted the point to make it 20-19. Receiving the kickoff, the Tide used its version of "Mr. Inside and Mr. Outside" to move into UW territory behind Brown's end runs of 15 and 14y and Hubert's center thrust for 23 to the 23. But Pooley tried a pass that went right into Cole's hands. But time ran out before the Huskies could mount another threat.  Fourth quarter action Afterward, Wilson complained, "The crowd beat us. We'll never play in Los Angeles again." Coach Wade: "Washington was undoubtedly one of the greatest football teams I have ever seen, and I am filled with much gladness that we won. The fact that the crowd at the game gave our team such wonderful support made the triumph a still more joyous one. The people here have been mighty courteous to all of us and I, as well, as the rest of the party, certainly appreciate it. Our team was in the best shape Friday it has ever been. They all fought hard and gave their every ounce–I am mighty proud of each and every one of them." The Rose Bowl head linesman proclaimed, "Johnny Mack Brown has the sweetest feet I have ever seen. The way he managed to elude Washington tacklers in his long runs was marvelous. He has a weaving elusive style that is beautiful to watch."

The Alabama team was hailed across the Deep South. In Montgomery, a spontaneous parade of thousands formed after the game at the central square. When the train from Pasadena pulled into New Orleans several days later, nearly one thousand Tulane students greeted the Crimson Tide. In other towns from there to Tuscaloosa, crowds gathered to express their pride and joy in the Rose Bowl triumph. When the train arrived in T-Town, the entire student body and most of the town turned out for a raucous parade. The team rode in wagons pulled by students. The celebration ended with speeches and tributes on the campus Quad. President Denny declared a school holiday.The school fight song, "Yea Alabama!," includes the lyric, "Remember the Rose Bowl, we'll win then." Historians consider the 1926 Rose Bowl the most important game in Southern football history. Andrew Doyle, a history professor at Winthrop University, wrote, "It was a sublime tonic for Southerners who were buffeted by a legacy of defeat, military defeat, a legacy of poverty, and a legacy of isolation from the American political and cultural mainstream." Alabama returned to the Rose Bowl the following year and tied Stanford 7-7. While in California, Champ Pickens arranged a Hollywood screen test for Johnny Mack Brown. That led to a lengthy movie career in which he appeared in more than 160 movies, mostly Westerns, between 1927 and 1966. His unique achievement is induction into both the College Football Hall of Fame and the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

View a video on Alabama football and the 1926 Rose Bowl. Reference:

Southeastern Conference Football: America's Most Competitive Conference, |

|