|

Football Short Story

Woody's Salvation - Part 3

1968: The Year That Saved Ohio State Football, David Hyde (2008)

Read Part 1 | Read Part 2

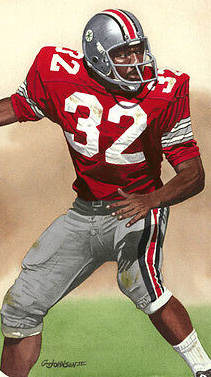

Jack Tatum was playing basketball with some friends one afternoon in the concrete jungle of Patterson, New Jersey, when a friend came running up with some news.

"Tate, I think that sweeper salesman went to your house and your mom let him in!"

Tatum took off running. Across their neighborhood, a con game had been operating. A white salesman was selling vacuum cleaners for $10 down and $5 a month into eternity. Some people never even got the vacuum. And now this guy was at Tatum's house? Talking to his mom?

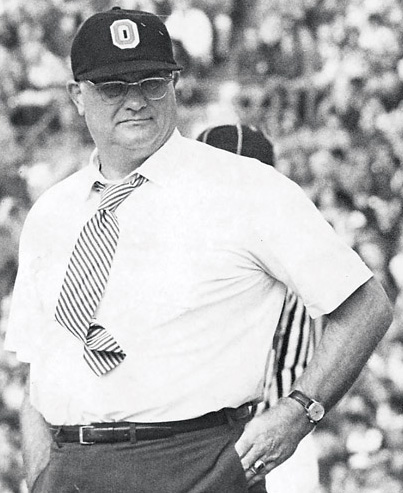

L-R: Woody Hayes; Jack Tatum Ohio State; Jack Tatum Oakland Raiders

Tatum ran through gaps in fences, down a couple of alleys, and was home in the time it took his adrenaline to rise. He planned to do some talking to this salesman. Or maybe his fists would do it, if necessary. As he stormed through the front door, ready for battle, his juices up, he heard his mom say from the kitchen, "Well, there's John David now."

Tatum turned the corner into the kitchen, looking for the vacuum salesman, ready for battle.

There sat Woody Hayes.

This was always the trick, getting the coach to this very seat in a recruit's life. Assistant coach Larry Catuzzi had done the legwork on Tatum for months, talking with his coach, visiting with his father, always showing Ohio State had everyone's interests in mind. Then he scheduled Hayes to make the full-court sell.

Tatum stopped in the kitchen, surprised. Hayes looked at him from a table chair. Tatum quickly recovered and traded the angry-son look for his star-recruit mask, the nonchalant one that said every coach in the land wanted him.

"Hi," he said.

"Hi," Hayes said, then turned back to Tatum's mom. He looked down at the piece of banana cream pie on his fork. "This is the best pie I've ever tasted. I've got to get the recipe for my wife."

His mom smiled. "It's made with a special crust and ...

For the next five minutes, as Tatum stood silently by, his mom and Hayes discussed how she made that banana cream pie. Hayes acted as if it contained the secret to life. It did, too, at least to Hayes. Because therein lay a secret of his success.

"My wife, I love her dearly," Woody would tell a recruit's mother, "but she just can't make an apple pie like you can."

When Woody was recruiting, he knew there was one person who could sway the deal-a parent. Often, it was the mother, though not always. Jan White's father, for instance, had a Penn State decal on the front door of their Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, home. When he heard Hayes was visiting them, he asked, "Why's he coming here?"

"I want to hear him out," Jan said.

"Why? You're going to Penn State, right?" his father said.

"We might as well listen to him," the son said.

After Hayes spent two hours at the Whites' dinner table discussing education, family, and philosophy-talking to the parents, that is, as Jan wondered why he was being excluded-the father turned to the son immediately upon Hayes's leaving.

"If you don't go to Ohio State," he said, "I will."

That was how Hayes could be. He had an intangible aura about him, an indefinable magnetic force that put people under his spell. The scouting report on him read: If you want to dislike him, you must never talk with him or hear him make a speech. As he discussed his bedrock beliefs-education, family, integrity-he seemed more like part of the family than a famous visitor.

Not every parent talked football, Hayes knew. But in an era when pro football wasn't a winning lottery ticket, they all talked education. Rarely did recruits see Hayes's inexplicable side, the schizophrenic one they'd see on the field, ripping hats, smashing glasses, and throwing fists. It was there, somewhere below the surface, of course. And sometimes he couldn't hide it. One recruiting class earlier, in the spring of 1966, Catuzzi was talking on the phone with a recruit from Cleveland named Frank Titas. Titas intended to be a doctor and was considering Michigan, too. Catuzzi put Hayes on the phone.

"Well, Frank, don't forget we run the fullback better than anyone in the country," Hayes said. "And you want to be a doctor. We have the best premed program in the country."

He listened.

"Uh-huh," he said. "So you're thinking of going to Michigan then?"

Pause.

"Well, Frank, you're not being patriotic," Hayes said. "You're not doing the right thing as an Ohio boy. This is where you belong!"

His voice was rising now.

"You don't belong up there! Not with them! Not with that team!"

He slammed down the phone.

"I hope he breaks his goddamned leg!"

That was Woody, too. But what Tatum saw that afternoon in his Patterson home was the rich personality of Hayes at work. After listening to the banana-cream-pie cream-pie conversation, Tatum left the room, figuring he wouldn't be missed. Evidently, he wasn't, either. When he returned an hour later, Hayes was telling his mom about General Patton and World War II. His mother began telling the story of her grandfather, who rode with General Grant in the Civil War.

After Hayes left the Tatum home that day, she said, "Jack, I kind of like that Mr. Hayes."

Oh, Lord, Tatum thought to himself, I'm going to Ohio State.

Tatum knew all about Hayes and Ohio State. His high school coach, John Federici, was a Hayes disciple. He ran Hayes's three-yards-and-a-cloud-of-dust offense. That was a fine high school offense, Tatum figured, because he played the featured position of fullback.

But Tatum saw himself following to Syracuse the famous black running backs such as Jim Brown, Ernie Davis, and Floyd Little. He even befriended a girl there on his recruiting trip and made plans to see her. Or maybe she had befriended him. Because later, on a recruiting trip to Michigan State, Tatum was talking with another recruit named John Brockington, and they made a startling discovery. They had met the same girl at Syracuse. She acted the same way with each of them. She had said she hoped to see each of them play there. And, well, their eyes were opened a bit.

Then again, nothing surprised Tatum too much. Not by this point in the game. He was educated on the streets and found recruiting to be one life lesson after another. He counted five new girlfriends at different schools from his recruiting trips. From some schools, he came home with hundreds of dollars in his pocket. He had been promised jobs and cars and gifts for his parents if he signed with the proper school.

Tatum was enjoying the bidding war for his services when he walked into Hayes's office on his visit. So far, nothing had been offered by Ohio State. He figured this is where it would happen.

"I don't know what the hell the other schools promised you," Hayes said, "but I'll make you only two promises. And I'll keep both of them."

They were the same promises he made in some form to everyone: To get a diploma and to become a better football player. That was it. No money. No cars. No girls. No grades. Nothing that Tatum had come to expect was a regular part of the recruiting process.

Tatum was surprised. He wasn't completely sold on the school. Ohio State's coaches, for the first of many times, couldn't get a read on his thoughts. But in the end none of that mattered. His mom had been won over since that first meeting in Patterson. She said how wonderful Hayes was. She said her son would get his degree there. She said how the holes in the soles of the coach's shoes showed he was a genuine person they could trust.

"I think you should go to Ohio State," she told him.

That settled it. He committed. Still, Catuzzi wasn't ready to celebrate until the national signing day on May 17. That spring, he was in New Jersey at a track meet in which Tatum ran the 100-yard dash. It was a slow cinder track. Tatum stumbled out of the blocks, but he quickly caught his stride and won the race in 9.9 seconds.

"Who's that?" Arizona State coach Frank Kush said.

Catuzzi looked at Tatum as if he had never seen him before.

"I don't know," he said.

|