|

How Glenn Warner Got His Nickname

Undefeated: Jim Thorpe and the Carlisle Indian School Football Team, Steve Sheinkin

When Glenn Warner enrolled at the Cornell University law school in 1892, he had never played football or even seen a game.

Now twenty-one, Glenn was a burly six foot two, with curly brown hair. He rode the train from Buffalo to Ithaca, in central New York, and walked around the Cornell campus, strolling pathways between grassy lawns and gray stone buildings. He wandered out to the sports field, where the football team was practicing.

Curious how the American version of this sport was played, he stood for a while and watched. He was startled to see the team captain, Carl Johanson, striding toward him.

Johanson looked Warner up and down and asked what he weighed.

"Two hundred and fifteen pounds," Warner said.

"Fine. Get on a suit right away. We need a left guard."

Warner was stunned. "Wait a minute," he managed to say. "I don’t know anything about the game at all."

"Never mind," Johanson told him. "All you’ve got to do is keep them from going through you and spoiling the play when we’ve got the ball. And when they’ve got the ball, knock the tar out of your man and tackle the runner. Perfectly simple."

The day after meeting Carl Johanson, Glenn Warner walked onto the Cornell football field for his first day of practice. The game had changed somewhat in the twenty-three years since Princeton had traveled to Rutgers (in 1869)—there were now eleven men per team on the field at once, for instance.

But the sport was still just loosely organized combat.

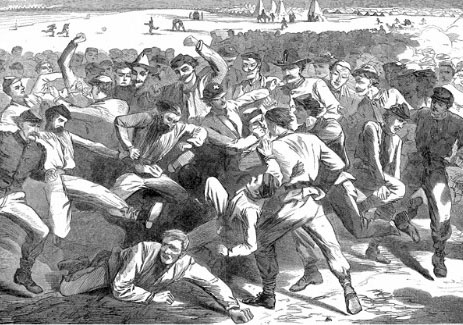

"Early-day football was anything but a parlor sport," Warner recalled, "many games being little more than free-for-all fights."

After only one practice, Warner was named starting left guard on the Cornell football team. Like everyone, he’d be on the field for every play, offense and defense. He learned on the fly.

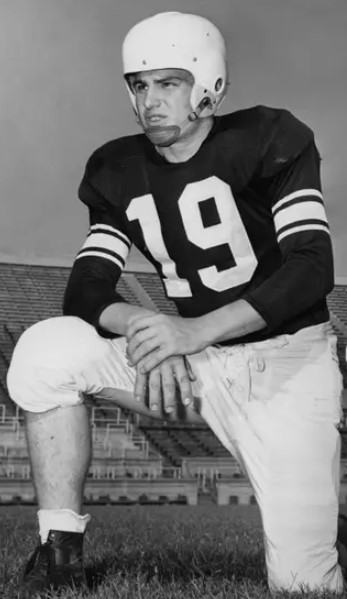

L-R: Glenn Warner at Cornell; "Soldiers playing football," a Winslow Homer Illustration Each play started with the teams lined up, facing each other, the ball on the ground between them. Before the play began, opposing linemen grunted at one another, spat, picked up dirt and threw it in each other's eyes. A lineman on offense snapped the ball to the quarterback, who then tossed it backward to one of the running backs lined up behind him. The man with the ball started forward, and defenders tried to knock him down. Teams could score by carrying the ball across the opponent’s goal line, or by kicking it through goalposts at the goal line. The ball itself was bigger and rounder than today’s ball, made for tucking under an arm or kicking, not throwing.

There was no such thing as passing; the forward pass was illegal.

Modern players memorize binders full of intricately choreographed plays. This was not the sport Warner learned. Early-day football was simple, repetitive, and—believe it or not—much more violent than today’s game. The typical play involved the ballcarrier plunging headfirst into a tightly packed wall of defenders, while his entire team pushed and pulled him—a "mass play," as it was called. Some teams even sewed suitcase handles onto the pants of their running backs so teammates could lift and drag ballcarriers through the pile. Defenders dove for the runner’s legs or leaped onto his back until he fell to the ground.

But the play still wasn’t over. It wasn’t over until the man with the ball quit moving. So while he squirmed and wriggled forward, more defenders piled on, and plays ended in massive, writhing mounds, inside of which guys would throw elbows and knees, scratch and bite, spit and choke, until the refs could untangle the heap.

Then, bruised and bleeding, everyone lined up and did it again.

The team on offense had three plays to move the ball just five yards. Five yards got you a first down—a fresh set of three plays to gain another five—so there was no need to do anything other than plunge straight ahead, play after play. "The stronger team usually was able to smash and grind the ball downfield in short, steady gains," Warner recalled, "until they had finally crossed the goal line."

And unlike today, football players wore little or no padding.

"In fact, one who wore homemade pads was regarded as a sissy," recalled John Heisman, an early player and coach for whom the Heisman Trophy was later named. Leather helmets were optional, and considered borderline wimpy. "Hair was the only head protection we knew," Heisman said, "and in preparation for football, we would let it grow from the first of June."

Warner joined the fashion, growing out his curly locks. "This sometimes had its disadvantages," he’d later say, "for when no arm or leg presented itself, a man made his tackle by simply knotting both hands in the opponent’s hair."

It was hardly enough to dampen Warner’s growing enthusiasm. "After I had gotten used to having my face pushed in and my head tramped on, I began to take an interest in the game."

One day, soon after he’d joined the team, Warner made a nice play at practice, and Carl Johanson shouted, "Good work, Pop!" Johanson never explained the nickname’s origin. Warner figured it had something to do with his being a couple of years older than most college freshmen.

Anyway, the name stuck. From then on, he was Pop Warner.

"Pop worked his way through school by waiting tables at a restaurant and played well enough to keep his spot at left guard." On the field, he paid special attention to the way his coach tried to get an edge using strategy—to use the word loosely. "If a player was too good-natured or easy-going," Warner explained, "the coach would tell one of his own mates to sock him in the jaw when he wasn’t looking and then blame it on the other team so as to make him mad."

Pop Warner was among the first coaches inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame when it began in 1951. He compiled a record of 319-106-32.

The First Legal Forward Pass

Highlights of College Football: John Durant and Les Etter (1970)

Football officials and college delegates held two meetings in New York in December and discussed various reforms. This led to the historic gathering on January 12, 1906 from which an organization that later became the National College Athletic Association (NCAA).

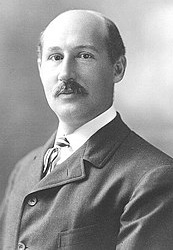

The Rules Committee, under the leadship of Walter Camp and Captain Palmer E. Pierce of West Point, made some far-reaching changes that opened up the game and reduced the hazards. Among them were:

Legalization of the forward pass

Establishing a neutral zone the length of the ball between the opposing lines

Increasing the yardage required for a first down from five yards to 10 in three downs

Reducing game time from 70 to 60 minutes and dividing it into two halves

L-R: Walter Camp, Palmer Pierce, Edward Cochems The year 1913 marked the beginning of the modern game. Here, briefly, is a partial list of the major changes made from 1907 to 1912:

The value of a field goal was reduced from 4 to 3 points, and a touchdown was increased from 5 to 6 points.

Outlawed were: the flying tackle, crawling by the ball carrier, and interlocking interference (a form of the wedge). It was also declared illegal "to use hands, arms, or body to push, pull or hold upon his feet the player carrying the ball."

Seven men were required to be on the offensive scrimmage line, thus eliminating the deadly mass plays.

The halves were divided into two quarters of 15 minutes each; the number of downs required to keep possession of the ball was increased from 3 to 4 in 10 yards; a player withdrawn from the game could return in any succeeding period. (Before this rule, a player removed from the game had to stay out.)

The field was reduced from 110 yards to 100, but 10-yard end zones were created in which forward passes could be caught.

The forward pass was at first hampered by many restrictions, but it was liberalized within a few years. At first, the pass had to cross the line of scrimmage within five yards from the point where the ball had been put in play. An incomplete pass when touched but not caught, could be recovered by either side (in effect, a fumble). If the pass fell to the ground untouched, the offensive team lost the ball. A pass caught behind the goal was a touchback, not a touchdown.

In 1910 the five-yard restriction was removed and the pass could cross the line of scrimmage at any point. However, it had to be thrown at least five yards behind the line.

In 1912 the receiver was protected by rules prohibiting defensive players from interfering with him. (Earlier, a player on defense could flatten the would-be receiver with a block, even clip him from behind, without committing a foul.)

Who tossed the first legal forward pass? The answer is not quite clear. However, we do know that the play was first used legally in a little-known game in 1905 between two small Kansas colleges: Fairmont (now Wichita State) and Washburn.

It came about this way. The forward pass was legalized during the 1905 season and used in the closing stages of that season. But the major colleges decided to wait until next year.

Fairmont and Washburn did not want to wait, however. They agreed to meet in a post-season game and try out the pass provided the rules committee would grant them permission to use it. Wires were sent to Walter Camp, who, following a meeting of the rules-makers in early December, told the two Kansas colleges to go ahead with their plans. The teams agreed to play on Christmas Day and both began practicing the forward pass. They had two weeks to go.

There is no doubt that the first legal forward pass was thrown in this now-forgotten game, but who threw it or which team initiated it will never be known. Both colleges claim the honor. Old press reports do verify the fact that forward passes were used by both teams but oddly enough, they fail to say who actually tossed the first one.

In any event, we learn that Hugh Hope, the Washburn quarterback, completed three passes to halfback Glenn Millice for a total of 25 yards, and Bill Davis, Fairmont's captain, completed two for a total of 15 yards. Both passers threw the ball underhand and it floated forward end over end. Neither team scored during the game.

Most football historians are not aware of the Fairmont-Washburn game and the few who are generally ignore it on the grounds that the forward pass rule was not officially entered in the rules book until January 12, 1906. They maintain–and with some justification–that the first legal pass was thrown on September 5, 1906 when Bradbury Robinson, a St. Louis Univesity halfback, tossed the ball forward to his running-mate, Jack Schneider, in a game with Carroll College of Waukesha, Wisconsin.

The St. Louis team was the first one to make full use of the new pass rule. It was coached by Edward B. Cochems, who was years ahead of his contemporaries in adopting the newfangled weapon.

He prepared for the 1906 season by taking his entire squad to Lake Beulah in Wisconsin for the two summer months. There, he studied the proportions of the clumsy, melon-shaped ball, which players called the "blimp," and realized that it had been designed for kicking and carrying, not for passing. He saw that the lacing was the only part of the ball that allowed finger purchase for throwing on its long axis. Before the first practice he told his players to put their fingers on the lacings nearest the end of the ball and throw it overhand with a twist of the wrist.

Eddie Cochems found an apt pupil in 6-foot, 4-inch Brad Robinson, who had a buggy-whip arm. In an early practice session Robinson, all excited, ran up to Cochems and said, "Coach, I can throw the darn thing 40 yards." His target was Jack Schneider and they worked together the rest of the summer. Cochems and his players could hardly wait for the season to begin.

What they did that fall stood the football world on its head. The slick Robinson-Schneider combination gave a perfect demonstration. Victims were Iowa (39-0) and Kansas (34-2). Against Kansas, Brad would shoot the ball hard and accurately to Jack Schneider at distances up to 50 yards. Opposing teams became panic-stricken as they stood helplessly watching long passes spiral over their heads for touchdowns. The defenders did not know what to do. When they dropped back to cover Schneider, the St. Louis backs darted through the line or around ends for long gains. Even the officials working the St. Louis games were stunned. One referee said that he had officiated at games around the country and had never seen anything like the St. Louis pass plays.

The team raced through an undefeated season, winning 11 games and scoring 402 points while yielding only 11.

The wonder of it all was that other coaches did not immediately take up the pass and do with it what St. Louis had done. Perhaps it was because St. Louis was a relatively obscure school deep in mid-America, outside of the Big Ten and far from the eastern seaboard, where the game had reached its highest development.

Little attention was paid to the pass in the East even though Yale beat Harvard with it in the 1906 game when HB Paul Veeder lofted a 35-yard pass to Clarence Alcott the right end, who caught it three yards from Harvard's goal line and was promptly downed. Moments later Yale scored the only touchdown of the game to win, 6-0. Navy beat Army, that year, 10-0, also by means of the pass.

In general, the East looked upon the pass with mild contempt–something not quite manly, like smashing the line. Furthermore, it carried severe penalties and was not worthwhile. The East could win games without it, so why use it? And anyway, the new play was a fad and would soon die out. So thought the East, with the exception of a few coaches. Pop Warner, Carlisle's coach, was one of the few.

"Okay, You Pass."

More Strange But True Football Stories, Zander Hollander (1973)

Lombardi demonstrated the same kind of toughness in coaching. On his second day in camp [as head coach of the Packers in 1959], after putting the Packers through a hard practice, he found 20 players scattered about the training room waiting to be attended to for minor injuries. "What's this?" he said in his brisk, loud voice. "You've got to play with those small hurts, you know!" The next day the number of Packers in the trainer's quarters had dwindled to two. One of them, A.D. Williams, an end, had his foot in a bucket of ice in order to reduce the swelling in his ankle. "How're you feeling?" Vince boomed. Williams hopped out of his chair and said through chattering teeth, "I feel better already, coach."

During his first week at Green Bay, the coach yelled so loudly and so often that he lost his voice. He insisted that injured players run in practice and warned, "You're preparing yourself mentally. Don't cross me. If you cross me a second time, you're gone."

Lombardi was as good as his word. Through clever trades he discarded the playboys, the shirkers and the troublemakers. Then he remodeled the spirit of those who were left. He harassed them out of the bars and into bed by curfew time. He forced them to attend meetings, meals and workouts on time. He let them know that his intentions were to make them tougher than the football players on other teams. "Football is two things," he said. "It's blocking and tackling. If you block and tackle better than the team you're playing, you win."

Schnellenberger Plays for Bear, Then Recruits for Him

Bear's Boys, Eli Gold (2007)

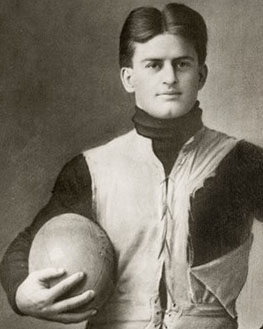

When he accepted the position as head coach at Kentucky in 1946, Paul "Bear" Bryant was only 32 years old. He was determined to win, even at a non-football school such as Kentucky. And he did. During his eight seasons with the Wildcats, he led his teams to a 60-23-5 record, took them to their first four bowl games, and in 1950 scored a Southeastern Conference championship.

The new coach impressed his players from the start. When George Blanda, who played for Bryant from 1946 to 1948, first saw him, he said, "That must be what God looks like."

As a high school player, Howard Schnellenberger was one of the best linemen in Kentucky. He was highy recruited and was ready to sign with Indiana when Coach Bryant came to call.

Bryant was not one to come empty-handed: he brought the governor of Kentucky along on the visit. Schnellenberger's dad was impressed, but his mother said it would be wrong to break the commitment to Indiana.

Coach Bryant, who knew Mrs. Schnellenberger was a devou Catholic, returned a few days later with the archbishop of her diocese. The deal was done.

Schnellenberger told Keith Dunnavant, author of Coach: "When Coach Bryant goes to war, he doesn't just bring the rifles, he brings the howitzers. That's the lesson I learned that day."

The military metaphors don't end there. According to Schnellenberger, football practices at Kentucky were exactly like boot camp. They were also reminiscent of Bryant's famous Junction Boys training camp, the pre-season session endured by Bryant's first team at Texas A&M at an old military base in the dusty town of Junction TX in 1954.

"When I saw the Junction Boys movie a few years ago, it ticked me off," Schnellenberger said. "I didn't know they were only out there for eight days. We were out there for six weeks!"

As Schnellenberger tells it, before there was a Junction, there was a Millersburg.

"He took us to a military camp north of campus. There were probably 132 freshmen on the bus. Only forty came back."

The Kentucky stories sound strikingly familiar to the scenes from Junction Boys. Guys climbing out of windows and sliding down drainpipes to escape in the middle of the night. A rock-strewn field. No water. Collapsing from heat stroke.

L-R: Bear Bryant, George Blanda, Howard Schnellenberger at Kentucky, Joe Namath Also familiar is the commitment and the bond shared by the players who made it through the experience and stayed with the team.

"He made it so hard," Schnellenberger said. "He was running off the quitters. The ones who stayed were committed."

As he told Dunnavant: "Coach taught me that hard work and sacrifice could get you somewhere in this world. He set the tone for my whole life."

Schnellenberger played for Coach Bryant for two years before Bryant left for A&M. He finished his playing years at Kentucky in 1956 as an all-American tight end under Coach Blanton Collier. He stayed on as Collier's assistant coach at Kentucky for two years. Then he joined Coach Bryant's coaching staff at Alabama in the national championship year of 1961.

"That was a real high time to be at Alabama," he said. "There was no rebuilding going on that year."

As an Alabama assistant coach, Schnellenberger is perhaps best remembered as the coach who recruited Joe Namath. When Joe was a high school senior in Beaver Falls PA, dozens of college coaches were after him.

Namath had committed to Maryland, but when he didn't score the required minimum on the college boards, he was up for grabs. The Alabama coaches snapped into action.

Schnellenberger knew Joe's older brother, Frank, who had been a freshman at Kentucky when Schnellenberger was a senior there. Frank was more like a father figure to Joe and thought playing for Bryant would give Joe the discipline and focus he needed.

Expecting to stay only one day, Schnellenberger arrived in town with just the clothes on his back. He hoped to hustle Joe out of town before other schools found out he was available. But the visit with his star prospect stretched into a week.

Not only did he have no change of clothes, Schnellenberger was running out of cash.

"Before I left, Coach Bryant went into one of his tin boxes and grabbed me some petty cash," Schnellenberger recalled. "I should have brought more on my own, but I didn't have much extra in those days."

Finally, he convinced Joe to come to Tuscaloosa. Schnellenberger had barely enough money to buy their plane tickets, and when a storm forced them to spend the night in Atlanta, Schnellenberger wrote a bad check for their hotel room.

At breakfast the next morning, Schnellenberger, who had only the change in his pocket, was incredibly relieved when Joe only ordered coffee.

Despite the ribbing his fellow coaches gave him for still wearing the clothes he had on when he departed a week earlier, Schnellenberger breathed a huge sigh of relief when he delivered his charge to the practice field.

As legend goes, Coach Bryant took it from there. He invited Joe to join him on his coach's tower–a first for a player or recruit–and the rest is history.

Too Thin, Too Slow, Wears Contact Lenses

Strange & Amazing Football Stories, Bill Gutman (1986)

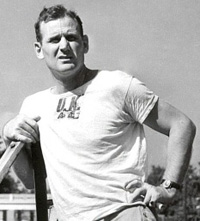

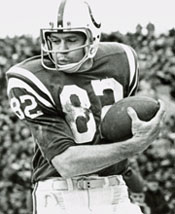

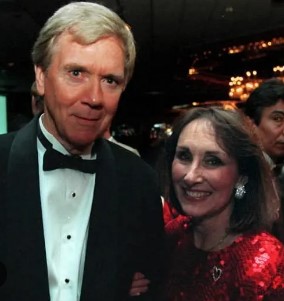

To some players, gaining an advantage on their opponents doesn't always mean deception or trickery. Take the case of Raymond Berry, the great pass receiver for the Baltimore Colts in the late 1950s and 1960s. Berry was the favorite target of quarterback John Unitas, and the two formed one of the greatest passing combos in National Football League history.

But Raymond Berry didn't have the natural physical attributes of many of the league's top receivers. He was tall enough at 6'2", but he was a thin 185 pounds and speed of many top wideouts and wore contact lenses during games. In addition, he wore a corset to protect a fragile back.

How, then, did Raymond Berry become one of the most productive pass receivers. The secret was dedication and practice. In fact, Raymond Berry may have practiced more than any receiver before or since. He practiced catching his patterns until each one was precisely orchestrated to perfection. And he practiced coordinating his patterns with quarterback Unitas until the two knew each other like a pair of matched bookends.

L-R: Raymond Berry, John Unitas, Sally Berry, Coach Raymond Berry In fact, Raymond Berry practiced so much that he often ran out of people willing to throw passes to him. For a while he fretted over the situation. Then he found an answer. The resourceful wide receiver found his own personal passer—his wife, Sally! It might have been a first.

"Sally's got a good arm," Berry would say whenever someone questioned the tactic. Anyone watching their workout agreed. Sally Berry wasn't going to put John Unitas out of a job, but she threw crisp ten- to fifteen-yard passes with good accuracy, more than enough to give her husband the kind of practice sessions he craved. She threw the ball just where he wanted it—high, low, behind him, over his head, right, left, again and again and again.

The practices were extremely important to Berry, who felt that all the good habits and good instincts had to be absorbed in practice. "In a game there's no time to think. Good practice habits keep you toned up and you do certain things without thinking in the games."

Berry's good habits made him the best split end of his day. He was instrumental in helping the Colts to NFL titles in 1958 and '59. In 1960 he had his best season with 74 catches for 1,298 yards and ten touchdowns. And his career stats place him among the pass receiving elite.

Always a stickler for detail, Berry didn't change his habits when he became head coach of the New England Patriots midway through the 1984 season. Perennial underachievers, the Patriots of recent vintage had never seemed to live up to preseason expectations. Berry was not only instrumental in turning the team around in '84, but in 1985 he surprised the entire pro fooball world by leading the upstart Pats all the way to the Super Bowl. Observers claimed that Berry's careful preparation and insistence on meticulous practice habits were crucial in enabling the team to put it all together. Bidding to become only the second wild-card team in NFL history to win the Super Bowl, the Pats were short-circuited in the final game by the rough, tough Chicago Bears.

Raymond Berry's pro coaching career is still ahead of him, but no matter what the future holds, nothing will ever dim his achievements as a player. On the gridiron his so-called eccentricities contributed to his success as much as anything else. For instance, to avoid jamming his thumbs, he built up their strength squeezing Silly Putty in his spare time. But of all the things Raymond Berry did to gain an advantage on the gridiron, perhaps the most important was proposing to a girl who had a durable and accurate throwing arm. Sally Berry might have been the most important quarterback in Raymond Berry's football life.

THE MAN WHO LET DOWN THE NFL WHEN THE NATION WAS MOURNING A Game of Extremes: 25 Exceptional Football Stories: About What Happened On and Off The Field, Roy Lingster (2022)

Sports have always been used as a way to bring people together. No matter their religion, their political beliefs, and their employment, folks from all walks of life are able to be joined by their love of sports. From basketball to baseball and especially to football, athletics have bound people and groups from all different walks of life.

Sports can bring people together in the best of times but can also bring people together in the worst of times too. In fact, the worst of times can be sports1 shiniest moments and the time they can work the most magic and create a soothing balm on an entire nation.

But sometimes sports do have to stop. Some events are so big, shattering, and shocking that they require the world of professional sports to take a few days to observe moments of silence. And when that doesn't happen, it can create serious tension and discomfort for literally everyone involved, including the players on the field.

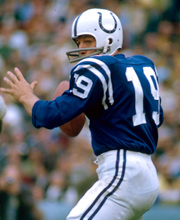

L: President John F. Kennedy at 1962 Army-Navy game; R: NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle The year was 1963, and it was a very different America than the one we know and love today. The president, John F. Kennedy, was youthful and incredibly unique. When he was elected back in 1960, he set a tone and an attitude about the country that was hopeful and exciting. After generations of leaders who felt ancient and stuck in a different era, Kennedy was forward-thinking and felt like a major step in the right direction to millions of Americans. Despite political differences, people from all parts of the country felt proud that the nation had selected such a significant leader.

The entire country was shattered on November 22, 1963, when President Kennedy was assassinated as he drove in a motorcade, waving to fans in Dallas, Texas. The generation that had voted for Kennedy had never known a trauma like that, and it literally left people in tears on the street.

The entire country came to a screeching halt. School was canceled, people were sent home from work, and people from coast to coast just shut down as America reeled from such a loss.

There were sporting events throughout the US that were promptly canceled following Kennedy's murder. But the NFL, which had a slew of games lined up just a couple of days after the 22nd, actually did not cancel their games.

Pete Rozelle was the man in charge of the NFL at the time, and he would live to regret this error for the rest of his life. Being the commissioner of the National Football League from 1960 to 1989, Rozelle had seen a whole bunch of major world events that could complicate the world of professional sports. But Rozelle had never experienced anything like the Kennedy assassination. Immediately after the shooting, there were calls from every direction telling Rozelle to cancel the weekend's games. Some people even called on Rozelle to end the season early. No one wanted to think about football, people said. Meanwhile, the AFL, still a separate entity at the time, had already cleaned its slate of games.

But when Rozelle spoke with Pierre Salinger, President Kennedy's press secretary, he decided the games would go on. Salinger encouraged Rozelle to keep the games playing on the weekend. And JFK's brother, Robert F. Kennedy, also said he wished the games would be played.

So that decided it: football would be on that weekend.

Ironically, one of the teams set to play just days after Kennedy’s death was the Dallas Cowboys. This was painful for multiple reasons, but most specifically because the word "Dallas" felt cursed in the days after Kennedy’s death. How would the team fare when they were representing a city that had just taken away the country’s leader?

Well, they didn’t fare well. When the Cowboys arrived in Cleveland to play the Browns, the players noticed they were not being welcomed with open arms. That wasn’t true by a long shot, in fact. Many people blamed Dallas and anyone associated with it for the death of the president. The people working in the hotel turned their backs on the Cowboys. People stared them down and kept their distance; the team even ate in small, disconnected groups in the evening as to not draw attention to themselves and who they were.

And the day of the game was awkward and uncomfortable. The stands, sparsely populated as the nation mourned, had a few people who yelled at the Cowboys during warm-up, telling them to go back home. The owner of the Browns, Art Modell, hired a group of off-duty policemen to protect the players, and he ordered them to never utter the word "Dallas."

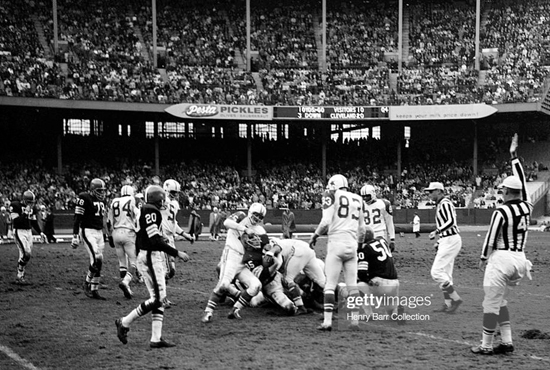

Browns-Cowboys play two days after President Kennedy's death It quickly became apparent that no one—not the players, the coaches, the refs, or the audience—wanted to really watch football on that day. But that is what they did. The players performed like zombies and seemed completely tuned out from the opening snap until the very last play. When it was all over, the Browns won 27–17, but no one seemed to really care.

The entire situation was so completely unique in the worst and most painful ways. The members of the Cowboys dreaded being in Cleveland and receiving such a cold reception, but they also couldn’t stomach the thought of returning to Dallas and feeling the horrible heartache of being there. The situation was made even more complicated by the fact that some of the people on the team actually knew Jack Ruby, the local Dallas business owner who had just shot and killed Kennedy assassin Lee Harvey Oswald. It felt like the country was on a dreadful roller coaster that everyone wanted to stop.

Years later, Rozelle would admit that he made the wrong call. He would later say he should have canceled the games and joined the rest of the world of professional sports in quiet solidarity and mourning. The lessons that Rozelle failed to learn would later be accepted and followed by Paul Tagliabue, who took over for Rozelle years later. He saw over the NFL in 2001, when the nation suffered another unfathomable tragedy on September 11, 2001. But Tagliabue, remembering what Rozelle had told him, canceled all games following the attacks of 9/11.

The tough decision to play after the assassination of JFK shook the world and the players involved in the league. In the end, it would be recognized as a bad mistake, but it would hold a special place in the history books, not only of America but also of the NFL. Forever shrouded in regret and pain, the games played after Kennedy’s death will never be forgotten.

Ed Hochuli's Nightmare

After Further Review: My Life Including the Infamous, Controversial, and Unforgettable Calls That Changed the NFL, Mike Pereira with Rick Jaffe (2016)

You know that feeling you get in the pit of your stomach when you make a mistake and there's nothing you can do to correct it? There's no amount of antacid you can take to make yourself feel better. Welcome to referee Ed Hochuli's nightmare.

The game took place in Denver between the Chargers and the Broncos [2008], and it was one of the most interesting plays I've ever been involved with. The Broncos trailed 38–31 with 1:17 left in the game, but had the ball, second-and-1 from the Chargers' 1-yard line. Denver quarterback Jay Cutler was attempting to pass the ball and it slipped out of his hand just prior to his hand moving forward, and it appeared to be a fumble that was recovered by San Diego linebacker Tim Dobbins. Game over.

However, Hochuli blew his whistle and ruled the pass was incomplete and the play was over. The replay official initiated a review and Hochuli went under the hood. He knew at that point that he made a mistake, and while he could reverse his ruling from an incomplete pass to a fumble, he could not give the ball to the Chargers. The only thing he could do was to put the ball back at the spot of the fumble with Denver retaining possession.

He was devastated, because he knew immediately that he had made the wrong call and there was no way for him to give the ball to San Diego, which would have essentially ended the game.

Two plays later Cutler completed a four-yard pass to Eddie Royal for a touchdown and then converted on a two-point conversion to give the Broncos a 39–38 victory.

I knew Ed about as well as anybody, and I knew how devastated he would be. One of the things I instituted when I began running the officiating department was to install phones into the officials' locker rooms at each stadium so I could contact them either before or after a game in case there was a concern or a problem. I'd say there was both a concern and a problem in this case.

Hochuli's call cost San Diego the game, and I knew how badly he would feel, so by the time Ed got to the officials' locker room, I was already waiting on the phone to talk to him. He got on the phone with me and I immediately pointed out all the good he had done for the NFL and all the great things he had done as an official.

L: Ed Hochuli works on his muscles. R: Hochuli explains his bad call to Chargers' coach Norv Turner. I explained to him that there was a reason that I put officials who were struggling on his crew, that there was a reason I always gave him first-year officials—because I knew with his preparation and his work ethic, he would make them better. I didn't want him to feel like his career was ruined with one missed call.

He was destroyed, so I had hope that by the time the phone call was over, Ed would understand just how important and valuable he was not only to me, but also to the officiating department. It's just one more example of how serious the officials take their jobs, and I knew I had to talk him off the ledge.

The following season, we changed the rule to prevent that from happening again. From that point on, when a quarterback pass-fumble play was ruled an incomplete pass but, in fact, was a fumble, the ball could be awarded to the recovering team, even though the team wouldn't be allowed to advance the ball. It's the same for a quarterback pass-fumble play now, as it is with a runner that is ruled down by contact when, in fact, it was a fumble. While that didn't make Ed feel any better, and he doesn't take too kindly to it, it became known as the Ed Hochuli Rule. Upon my further review, even the best make mistakes. It wasn't the first and it won't be the last. But you have to look at a person's total body of work to determine his value. Hochuli missed the call and he and his crew suffered a substantial downgrade. It was enough to knock most crews out of the playoffs, but not Hochuli's.

But as I said before, this crew battled back and ended up working a wild-card game that postseason, much to Commissioner Roger Goodell's chagrin. Due to the magnitude of the mistake, Goodell didn't want Hochuli or his crew in the postseason. But based upon their overall season performance, how could I not put them in the playoffs? They battled their asses off and earned it over the final 14 weeks of the season. What would that have said to an officiating crew if I told them that since they had made a mistake in Week 2, they wouldn't make the postseason? It would say that I suck as a boss. It wouldn't be right and it wouldn't be fair.

Needless to say, Goodell and I didn't always see eye-to-eye on things.

"It's Gonna Be a Heavyweight Match"

Da Bears! How the 1985 Monsters of the Midway Became the Greatest Team in NFL History (Kindle), Steve Delsohn (2010)

Aggression was a weapon which Mike Ditka believed in. During the 1960s, he had been a relentless tight end for the Chicago Bears. Now, at age 45, he was in his third year as their combative head coach. Thus he viewed the next football game as more than a game. It was a litmus test to see just how ferocious his 1984 Bears were.

Aggression was a weapon which Mike Ditka believed in. During the 1960s, he had been a relentless tight end for the Chicago Bears. Now, at age 45, he was in his third year as their combative head coach. Thus he viewed the next football game as more than a game. It was a litmus test to see just how ferocious his 1984 Bears were.

"If you want to defeat your opponent, you got to out-hit him," says Ditka. "People say, 'Well, you need to out-think him.' No! You gotta out-hit him. That's what football players understand. It's like a boxer. You hit him in the nose enough times he's gonna respect you. The Raiders were always a physical football team, and that's what we talked about before the game. I said, 'We're going toe to toe with these guys. It's gonna be a heavyweight match, and we're gonna slug with them.' "

On November 6, 1984, the Bears mauled the Raiders 17–6. This being Chicago, it was windy and cold on that Sunday afternoon at Soldier Field. This being the 1984 Bears, the offense did just enough, led by its beloved warrior Walter Payton, who gained 111 yards and scored both of his team's two touchdowns. On defense, the Bears made the Raiders look weak and confused, forcing 3 interceptions and 2 fumbles and sacking the Raider quarterbacks 9 times. Read that again—9 times—because it doesn't happen too often. The single-game NFL record is 12, which is held by five different teams, including the '84 Bears, who did it later that season against the Lions.

L-R: Mike Ditka carried off after Bears won Super Bowl; Walter Payton; Emery Moorehead Against the Raiders, it seemed as if the Bears competed against each other to see who could beat the snot out of the quarterback first. First they fractured Marc Wilson's arm and knocked him out of the game. Then they knocked out his replacement, David Humm, with a knee injury. Wilson was forced to reenter the game and found himself getting knocked out a second time. Curry Kirkpatrick, writing for Sports Illustrated during his heyday, was deeply impressed. "So brutal was the Bear onslaught that Al Davis was seen covering his face with his hands. Just breathe, baby."

The NFL's closest observers were also starting to see that the Bear offensive line had become increasingly nasty in its own right. Kurt Becker started that game at right guard for Chicago. A six-foot-five, 280-pound Michigan graduate with a maniacal streak, he frequently tangled that Sunday with future Hall of Fame lineman Howie Long, who later told Sports Illustrated he finally screamed at Becker, "I'm going to get you in the parking lot after the game and beat you up in front of your family!"

Becker says Long tried to follow through on his threat. "Howie was out of his mind by the end of the game," he recalls. "He tried to come into our locker room and confront me. Then he wouldn't get on their team bus. He was looking for me in the parking lot."

Years later, Emery Moorehead, Chicago's multitalented tight end, ran into the great Raider running back Marcus Allen, and they began reminiscing about the day the '84 Bears made the '84 Raiders look soft.

"Marcus said, after we knocked out both of their quarterbacks, they wanted to put in Ray Guy, their punter, because he was supposed to be their emergency quarterback," says Moorehead. "But Guy refused to go in. Then all of them were arguing at halftime about who was going back in—was it gonna be David Humm or Marc Wilson? Nobody wanted to go back in. That's how intimidating our defense was then. You can't even hit guys today the way our defense hit them. You'd be suspended."

Ditka, who doesn't joke about this kind of thing, says the 1984 win against the Raiders "was the most brutal football game I've ever watched. Did you see how many guys they were carrying off the field for both teams?"

L-R: Kurt Becker, Howie Long, Ray Guy, Jim McMahon In the second quarter, the Bears lost their own starting quarterback, Jim McMahon, when he scrambled away from the pressure and ran for a first down before getting pinned between two Raiders. On the CBS telecast it looked fairly benign, but in reality one of the Raiders had struck McMahon in his side with a helmet. His offensive teammates told him to leave the game. He refused and remained for three more plays, but at halftime he had trouble breathing. McMahon tried to play again in the third quarter, and this time his offensive linemen ordered him to the sideline.

"Jim got hit in the kidney, and it came over the bone in his rib cage and his kidney got lacerated," says McMahon's longtime agent Steve Zucker. "I was in the stands, and I met him in the locker room. He was pissing blood, I mean pure blood, and he was in intense pain. He was in agony."

Adds McMahon, "They wanted to remove it, but I knew my career would be over. The bottom part of it was gone, and it was cut in about five places. It was bleeding for two days. The doctor told me, 'Look, you're gonna die if we don't cut it out.' I said, 'You can't cut this out, you cut it out and I'm finished. Just keep giving me the morphine and leave me alone.'

McMahon spent the next ten days in the hospital. Right after the Raiders game, Bears trainer Fred Cato told reporters, "At this point, I will say he will play again this season. But he will miss four weeks. There was no rib damage, no other organs were injured, but there was a lot of pain, and he did urinate blood. On the positive side, he didn't rupture the kidney, which could have ended his career." Cato turned out to be wrong about McMahon returning after a month. For McMahon, the '84 season had just ended. And just that abruptly the Bears lost their momentum. They were 7–3, but now it seemed less likely that they would keep winning enough to make the playoffs. If they did qualify for the postseason, their quarterbacks would be Steve Fuller and Rusty Lisch.

Psychological

Out of Bounds, Jim Brown with Steve Delsohn (1989)

The Bronx, New York. Yankee Stadium. October, 1963. Winter is moving in. So are the New York Giants. And they're attacking my eyes.

I wasn't happy, wasn't quite surprised. Though you'll always find scared individuals, the prevallent nature of the professional football player is that of a soldier of fortune. He's trained and willing to bust people up.

The Giants were sophisticated assassins. Maybe it was living in New York: guys like Frank Gifford, Jim Katcavage, Andy Robustelli, seemed hipper, classier, than the average guy in the NFL. I had big respect for the Giants. They were football intellectuals, the smartest team in the league. Also the most calculating. Other teams would have one or two thugs who'd randomly jump you, hit you in the head. New York did nothing helter-skelter. The Giants would determine, as a unit, who they were going to get, then go out and get him. I used to envision them in their dressing room: "Look, today we're gonna fuck up Jim Brown's eyes. And here's how we're going to do it."

Jim Brown runs against the Giants. Loose rules. Hard men. Not a lot of cash. It made the old NFL a primitive place. I accepted the standard rough stuff, knew it was part of my sport. Still, the first time I carried the ball against the Giants, I knew something was up. We used to wear those two-bar masks; the bottom of the nose to just above the eyebrow was exposed. As I was going down my first carry, a guy stuck his hand inside my helmet, scraped my eyes. Next carry, my eye got hit by a forearm. As the first half went on, I guess the Giants got pretty blatant. Rosey Grier, their huge defensive end, started screaming at his own teammates: "WHAT THE HELL ARE YOU DOING THAT FOR?"

Me and Rosey were real friends, the Giants knew it. I don't believe they sent him that morning's memo.

Rosey even confronted the officials, told them his teammates were after my eyes. The officials didn't call anything. I'm not singing the blues: in our era, that was not unusual either. The game was not remotely as commercial, the refs weren't out there to protect careers. Guys got away with serious mayhem.

For me that particular day, that presented a problem. In boxing, guy hits you in the groin, ref is dreaming about his chick, it's simple: you crack the other guy in the groin. To keep it semi-clean in football, you need the official, especially if you're a guy on offense, particularly a runner. A runner can't really retaliate, all he can do is go nuts, start a fight. Then his ass is ejected, the defense is grinning.

I came in at halftime against the Giants, sat by myself. It was a strange, memorable moment. Time diffuses memory, and people today think it was all power, speed, and instincts. I did have those talents, but a major part of my edge was psychological. Normally, I was the one who messed with people's mind. Now the Giants had penetrated mine.

Sitting alone, I was thinking, Damn. Do these guys have me? Do I complain? Do I start a fistfight?

Have they broken my will?

I was scared. Not physically. You can't play in the NFL, not for long, if you're frightened of taking punishment. No way you can play running back.

What scared me was the Giants' tactics. Specifically, I was afraid that those tactics would stop me from performing. In my entire life, fear of not performing is the greatest fear I have ever felt.

I wasn't alone. Bill Quinlan, a defensive end, was one of the roughest, toughest guys on the Cleveland Browns. He would throw up violently before every single single. Quinlan's boogieman was inside his stomach, tearing away.

Being the star of my team, perhaps the most scrutinized man in the league, my boogieman was twenty feet tall. The pressure on any big star is somehow unique. You're in the dressing room before the game, younger guys are glancing at you, veterans depending on you, 60,000 people want to be entertained–brother, you can't have an ordinary game.

That shit would scare me to death. I'd be trying so hard to concentrate, start thinking, Wow! I think I would rather not be here.

At first when I had those thoughts I was miserable. I felt so damn guilty. Then I talked to other people, not my teammates or opponents, but men I respected in other professions, and learned that fear is perfectly natural. It's essential–if men didn't blink when you threw something at their eyes, if they had no fear, they wouldn't survive. I learned that fear is a gift from God.

I was set free! Once I admitted I had fear, I used that sucker. Made it my ally. Okay, I have a contest this afternoon, and I am Fucked Up. By gametime, can I take this totally messed up feeling, pull my stuff together? Can I come face to face with the Devil–and still perform? When I discovered I could, it was a hell of a piece of knowledge. By kickoff, I could grip my fear, transform it into power.

Unfortunately, during halftime against the Giants, I forgot all that. I didn't have a clue. Not only had they rattled my mind, the Giants had messed up my eyes. I felt like I was looking through a thick curtain. Then halftime ended. End of soul search. I thought, Man, I got a game here. They go for my eyes again, I'll deal with it then.

I never discovered what I would have done. First time I got the ball, I broke a long one–touchdown.

Next time we got the ball, I scored another strong TD. That was that: the Giants stopped going for my eyes. I think I know why. I've always felt that competition, stripped to its essence, is a battle of will. Skills, conditions, even luck may vary. Only one thing is constant: break an opponent's will, you'll beat him every time. Control a man's mind, his body will follow.

The Giants probably didn't know it, but on that day, they came close to breaking me. When I wouldn't succumb, I think they lost their will. And we beat them, 35-24.

There was still the matter of my eyes. Two days later they were still blood-red and blurry. I pulled aside one of our coaches just before practice.

I said, "Coach, my eyes haven't cleared up. Maybe I should go see the doctor."

He said, "Yeah ... can you go after practice? I don't want the other guys to think you're hurt. It would screw them up."

So I practiced, then I snuck to the doctor that night.

"Where Do I Sign?"

From Ashes to Glory, Bill McCartney with Dave Diles (1995)

When future Colorado head coach Bill McCartney was an assistant coach under Bo Schembechler at Michigan in 1979, he was involved in the recruitment of WR Anthony Carter in Riviera Beach FL.

Anthony had staggering high school statistics, scoring 59 touchdowns, an All-American in both football and basketball. He's the fastest person I've ever seen on a football field, and he had so much speed in basketball that he'd get the ball at the end of the court on an in-bounds pass, and still beat everybody else down the floor on the fast break. He was playing basketball when I first saw him and talked him into coming to Michigan as one of his five on-campus visits.

That, in itself, was a major accomplishment, since he never seemed more than lukewarm about the whole thing. I'm sure he wouldn't even have agreed to a visit had not some of his close advisers spoken so highly about about the school and about Bo Schembechler. Besides, Anthony had already signed a letter of intent with Florida State, and that discouraged a lot of schools. But in those years, that signing wasn't binding on Big Ten schools, and we pulled out all the stops to ensure an impressive visit to the Michigan campus.

Everything cooperated except the weatherman.

It never got above zero the entire weekend! Knowing that Anthony was accustomed to the Florida sunshine, we decided to be as resourceful as possible. We got a special permit from the Wayne County Sheriff's Department at Metropolitan Airport outside Detroit and parked a jeep close to the spot where Anthony would exit the airport. And whoosh! Right off the plane, right into a vehicle that had been left running with the heater turned up very high. All weekend long, we did things door-to-door whenever possible, and when we did have to step outside with him, we jumped into one heated vehicle after another.

Not once during the entire weekend did I get any indication that Carter was giving Michigan a second thought. He was being accommodating, that's all. I took the plane back to Florida with him since I had to go there for additional recruiting, and I kept the conversation going by reminding him of all the advantages that would be his by joining the Wolverines.

"There's one thing you'll have to overcome if you decide to sign with Michigan," I told him. "You'll have to face the fact we do have some winter here."

He turned and looked straight at me and said, "You know, it's not all that cold there."

I knew then our plan had worked, but we didn't seem all that much closer to getting Anthony Carter. In fact, I realized that we were a distant third behind Florida State and Texas. But when the national signing day arrived, Carter didn't sign with anyone.

L-R: Anthony Carter, Bo Schembechler, Bill McCartney I arrived in town late Wednesday afternoon. I tried to get an appointment to see Anthony on Thursday but was unsuccessful. Friday afternoon I happened across Carter on the street. I was driving a rental, he was riding a bicycle. I pulled up alongside and asked if I could talk to him. He just stared at me and pedaled away.

His basketball team was starting state tournament play that night and won the game, meaning another game the following night. I stayed around, knowing I was playing a long shot. Carter's team was beaten the second night, a Saturday. I stuck around through Sunday and still hadn't even had a chance to make a final appeal.

Monday morning dawned. I wolfed down some breakfast and headed to Suncoast High School, trying one last time to see Anthony. I saw his coach instead.

"I've been here since last Wednesday, Coach," I pleaded, "and all I want is five minutes with Anthony. If he tells me no, or absolutely won't talk to me, then I'm on the next plane to Michigan. But I want to hear it from him."

The coach agreed to get Anthony between classes. In five minutes he returned, telling me Carter hadn't come to school that morning. The coach had called Anthony at home, encouraging him to give me just five minutes. While Carter had agreed, the coach alerted me that Anthony might not be in the best of moods. Apparently he'd been up all night. Anthony's girlfriend, who was going to college in another part of the state, had managed to get into town and Anthony, the girl, and a recruiter from another school had spent the night in the recruiter's car, talking.

But there was a part to the story that neither the coach nor I had discovered yet: It seems that Anthony's mother had gotten up in the early dawn to get ready to go to her job as a cleaning lady in a small motel in town. She found the threesome, still together after a night spent in the recruiter's car. It was then Anthony told her he had made his decision about college. And it wasn't Michigan.

Mrs. Carter, a tiny woman, looked up at that recruiter and told him, "You take that girl and dangle her in front of my son like that? I'll never sign for my son to go to your school."

Mrs. Carter was gone by the time I arrived and knocked at the door. Anthony came to the door, glanced at me for a second and, without saying a word, sort of shoved the screen door open. Then he walked away. It was clear to me what he was saying: Come in if you must, say what you have to, and then leave.

I'd had six days to get my spiel down, and I wasn't going to blow it then. I pulled up a chair and sat facing him.

"Anthony, I've been here six days now, and all I want is a chance to talk with you. I'm going to take just ten minutes and after that, if you don't like what I've said, you'll never see me again."

I did every bit of the talking. I never asked one question. I just told him what Michigan to offer—no special inducements, no prizes, no deals, just a chance to get a great education and play in a great program. And I told him everyone else had probably told him that Bo Schembechler was a running coach and that he'd be wasting his talents there. Bo's stubborn and Bo's a bear on defense and strong running and good kicking—but Bo's also a true pro. I assured Carter his talents would be utilized.

When I finished, I merely said, "That's it. What do you think?"

Anthony Carter, in cold, simple terms, looked at me and asked, "Where do I sign?"

I almost fell off the chair.

He said we'd have to go to the motel to see his mom. When we arrived there, Anthony told her, "This is the coach from Michigan. I'm going to Michigan. We need you to sign papers."

She signed them, but Anthony didn't. He said he wanted to go to school so his coach could witness his signing. Once at school, doggoned if we could find the head coach. I was frantic, thinking Anthony might change his mind before we could complete the transaction. After all, just a couple of hours earlier he'd been all set to go somewhere else. We finally located an assistant coach, and Anthony agreed to sign in his presence. Once his name was on the paper, I telephoned Schembechler. He was flabbergasted. He chatted with Anthony briefly, and then I told Bo he just had to come to Florida for the formal announcement. Bo was on the first plane leaving Detroit Metro.

You want a storybook ending to this? The first time Anthony Carter touched the ball as a freshman, he ran 76 yards for a touchdown with a punt return. He scored 37 touchdowns for the Wolverines, averaging a gain of 17.4 yards every time he came in contact with the football at Michigan. He gained more yards per play than any person who ever played college football. He became a three-time all-American, was named captain of his team and got his degree before becoming a millionaire with his extraordinary exploits in the National Football League.

|