|

Bad Officiating and the First Forward Pass

Echoes of Georgia Football: The Greatest Stories Ever Told (2006)

Glenn "Pop" Warner became the head coach of Georgia in 1895.

Coach Warner's first victory came when Georgia romped over Wofford in the opener at Athens, 34–0. This set the stage for the clash with North Carolina, Georgia's most illustrious foe up until that time. The Tar Heels had been playing football seven years to Georgia's three, and their annual game with Virginia was well on the way to becoming a southern classic. It was a feather in Georgia's cap just to have Carolina on the schedule, even if the Red and Black was considered outmatched.

The game was played at Atlanta's Athletic Park, and some of the spectators, unwilling to remain on the sidelines, stationed themselves on the field squarely in back of the offensive team. One of these was John Heisman, the Auburn coach, who was scouting Georgia. Early in the game, North Carolina, backed up near its own goal line, sent its punter, [George] Stephens, back in kick formation. Rushed too badly to get his punt away, Stephens retreated a few yards only to find himself trapped between the oncharging Georgia linemen and the fans who had lined up behind the Carolina team. Coach Heisman, for one, had to duck to keep out of the way. Finally, in desperation, Stephens flung the ball forward, over the scrimmage line, into the arms of a startled teammate, [Joel] Whitaker, while Georgia's secondary watched in disbelief. "Before the crowd was aware of it," wrote a reporter, "Whitaker was running through all obstructions like lightning with the ball, and had touched the ground back of the Georgia goal."

L-R: Pop Warner, John Heisman, Walter CCamp Since the forward pass had no place in the rules of the day, the fans were in an uproar. But the referee allowed the play to stand, with the observation that he "didn't see it." Men began squaring off, and "only the presence of Chief Connolly and the quick and determined work of the patrolmen prevented a general fight." Order was restored, and the game went on to its conclusion without another score being put on the board.

The Stephens-to-Whitaker pass became something of a cause célèbre. "It was clearly a fluke," said the Constitution, while the Journal called it a "clever trick." The play went down in athletic history as the first of its kind in the annals of football; it later would have an important role in the development of the modern sport. Ten years after the game, John Heisman wrote to Walter Camp of the incident, recommending that such a play be legalized in order to open up the game. The following year, 1906, the forward pass officially entered the rule book.

North Carolina evidently felt some guilt over the spectacular play and, immediately upon its return to Chapel Hill, accepted Georgia's challenge to come back and play the game over again five days later. The rematch was set for the same field on October 31, which was to be Atlanta Day at the huge World's Fair being held at Piedmont Park. Although Athletic Park was several miles removed from the exposition, it was anticipated that a large segment of the fair crowd would be lured to the gridiron.

But things did not work out as well as had been expected. Atlanta Day happened to fall on the same date that an earthquake was felt throughout the United States, Atlanta included. "A great many people were awakened at an unusual and unreasonable hour this morning," said the Journal, "and a great many were also badly scared." Football was crowded out of the general conversation that morning, but by noon a few diehards had inquired of the weather bureau what conditions they might expect by game time. "I don't know," said a weatherman. "Earthquakes are not in my line."

As it turned out, a miserably cold rain began to fall, and only 350 spectators showed up at Athletic Park. By the end of the game, "the players looked more like well-diggers than anything else." Still, the teams put on a remarkably good show, with Carolina winning once again, 10–6. This time the Georgians went home satisfied they were beaten.

The team ran into foul weather again on November 9, but beat Alabama at Wildwood Park in Columbus, 30–6. It was the first intercollegiate game in the south Georgia city, but the crowd, because of "the drenching rain together with the inequality of the teams, lost all interest…before it was over."

Nine days later Georgia was back in Atlanta for a Monday game with Sewanee. Early in the first half, Georgia's "Cow" Nalley blocked a punt with Sewanee recovering on the scrimmage line. "The Georgia boys claimed the ball," wrote a Constitution reporter, "and Referee Dorsey was appealed to. He pleaded ignorance of the rules." (It seems that Mr. Dorsey had been sitting in the stands ready to enjoy the game when he was asked to serve as referee. He informed the captains he was "somewhat rusty" but got the job anyway.) The matter of the blocked kick was referred by Dorsey to the umpire, a Mr. Seixas, who, after chasing Coach Warner off the field, decided in Georgia's favor. A touchdown followed quickly, and tempers began to flare.

A short time later, Georgia tackle W. B. Kent, who once was criticized by a reporter for being "too polite," came into conflict with Whitaker, a Sewanee end. "Kent was slugged by Whitaker," said the Constitution, "and a lengthy squabble ensued. Umpire Seixas ordered Whitaker out of the game but very wrongly said he would let him come back if Captain Stubbs would consent. … After much unnecessary kicking…Whitaker attempted to show a spot on his leg where he claimed Kent had bitten him. There was no bruise, however. Captain [Stanley] Blalock [of Sewanee] declared he would not play if Whitaker went out, but finally the matter was adjusted, Whitaker leaving the game." Georgia went on to win, 22–0.

On November 24, under a headline, "Looks Like Robbery," a Constitution reporter told the story of Georgia's defeat by Vanderbilt in Nashville on the day before. Midway in the second half, with the score 0–0, Georgia's Pomeroy, after a handoff from Barrow, was piled up in the middle of the line. Pomeroy yelled, "Down," an act that normally ended a play in that day regardless of the referee's whistle. But seconds later, Elliott of Vanderbilt was seen holding the ball aloft. Georgia claimed he had merely picked it up after the scrimmage and was handing it to Walter Cothran, the Red and Black center, prior to the next play. At any rate, said the report, "Someone cried run, and Elliott ran, making a touchdown."

A furious Pop Warner rushed out on the field to register his complaint, but again he met his match. W. L. Granberry, the referee, informed the Georgia coach that he was a Princeton graduate, class of 1885, that he had officiated at every game in Nashville since that time, and that, moreover, he had never had a previous complaint. This was too much for Warner. He gathered his Georgia boys around him and walked off the field. Vanderbilt was awarded the victory, 6–0.

The final game, against Auburn, was scheduled for noon of Thanksgiving Day as an added attraction of the World's Fair at Piedmont Park. The playing field was laid out on the eastern border of the exposition grounds, which had been graded for Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show. The early kickoff was planned to allow the spectators to see the game and still have time to enjoy John Philip Sousa's band and attend the exhibits later in the day.

Actually the game started at 3:00 after a long argument over the officials. Both teams agreed on the referee, linesman, and timekeeper, but could not come to terms regarding the umpire. The Georgians wanted Mr. Seixas, who had satisfied them with his work previously, while Auburn preferred a Mr. Taylor for a similar reason. In a last-ditch compromise, both men were appointed and the game was on.

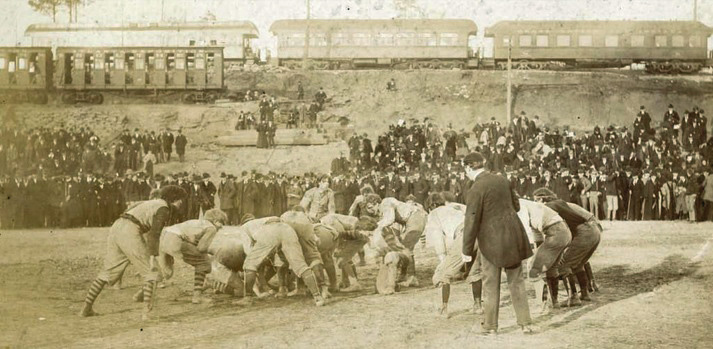

1895 Auburn-Georgia game By that time, things were in a chaotic state. A good number of the 60,000 visitors to the fair that day crowded onto the playing field area, many of them curiosity seekers who had never before seen a football game. The condition of the playing field, which had been romped over for weeks by Buffalo Bill's cowboys, Indians, and horses, can well be imagined. "The beginning of the game was the scene of the wildest and most disgraceful confusion," wrote a reporter. "The spectators massed about the players and only a select and energetic few could see the game at all." Finally a student, "with white cap and glasses," relieved the situation temporarily by tearing down a wire from the grandstand and improvising a fence on the sideline.

The Georgians were favored because of their powerful showing against North Carolina, Sewanee, and Vanderbilt. But they had neglected to scout Auburn, while the Alabamians' new coach, John Heisman, had personally watched his opponents perform. Georgia learned its lesson quickly. Reynolds Tichenor, the flea-sized Auburn quarterback, seized control of the game and exploited Georgia's weaknesses, sending his running backs on repeated long gains.

Georgia found itself behind, 10–0, before finally getting a second-half drive underway. The Constitution described the scene: "Ball is on Auburn's 10-yard line. Excitement is intense. The crowd has poured upon the field and is absolutely unmanageable. Nalley goes one yard, Farrell five. The men can hardly hear the signals. Kent, with goal three yards away, springs around left end, making a detour of 20 yards and getting a touchdown."

But that was Georgia's last assault. Auburn charged back upfield, through the Georgia line and milling crowd, and made the clinching score. Georgia was upset, 16–6.

Savior of Football

Bill Stern's Favorite Football Stories (1948)

On October 31, 1897, in a football game between Virginia and Georgia, the star of the Georgia team, an 18-year-old boy named Richard Vonalbade Gammon suffered head injuries from which he died that night.

On November 5, 1921, 24 years after his death, the University of Virginia presented to the University of Georgia a bronze plaque symbolizing the spirt of the Gammons, mother and son. The plaque shows a mother with her son embraced in her right arm and holding up a shield with her left. On the shield is inscribed, "THE CAUSE SHALL LIVE IN WHICH HIS LIFE WAS GIVEN." The background of the plaque reads "ROSALIND BURNS GAMMON, 1851-1904, AND VONALBADE GAMMON, 1879-1897," and below the instruction reads: "A MOTHER'S STRENGTH PREVAILED."

Gammons Plaque at University of Georgia This is the story behind the plaque.

On the afternoon of October 31, 1897, Georgia was playing its traditional rival, Virginia. The star of the Georgia team was a youngster named Von Gammon. Suddenly, during that hard-fought game there was a furious mixup as the players of both teams clashed near the Georgia goal-line, one team determined to score, the other just as grimly determined to prevent a touchdown. When the players on the ground were unscrambled, one was found at the bottom of the human heap–unconscious. He was the star of the Georgia team–Von Gammon. He was carried off the field suffering from a brain concussion. By morning, Von Gammon was dead.

The Georgia team quickly disbanded. Protests against the brutality of football rose to fever pitch. An anti-football bill was introduced in the State Legislature–quickly passed and forwarded to the governor of the state for his signature. It looked as though football in the South was doomed. Meanwhile, the rest of the country watched Georgia, waiting to take similar action.

But in football's darkest hour, a woman came forward. For that woman wrote a stirring letter to the Governor of Georgia, begging him not to sign the bill. She pleaded with the governor not to use Von Gammon's tragic death as an excuse to outlaw the game. That woman's touching appeal helped save college football in the South. For the bill never did become a law. Strangely enough, that woman was the mother of Von Gammon, the Georgia star who had been killed!

For several years thereafter, football grew and prospered–when suddenly, the game was once again threatened with destruction. In the season of 1905, 32 players were killed! This frightful toll of human life brought down public wrath. Eighteen state legislatures introduced bills to make football-playing a felony.

This time a man came to the rescue. He was an important man–a man people listened to. That man summoned college officials to discuss plans to save football. His plea was strong and vigorous. He convinced the nation that college football was a game worth playing, worth improving and worth saving. Under his sponsorship, there was organized what is today the National Collegiate Athletic Association. Rules were made to eliminate rough playing that might cause unnecessary injuries and death on the gridiron.

From that day, college football became greater in popularity than ever before. Colleges which never had tried the game now organized teams to carry their colors into gridiron battle.

Football's preeminence today can be traced to that one man who helped save the game. This man had never played football himself. But he was a fighting two-fisted man who will always be remembered, not only by the sports world, but American history as well. This man who helped save college football was the 25th President of the United States–Teddy Roosevelt.

The Game: West Point NY, November 9, 1912

Darin Watkins, Chance for Glory: The Innovation and Triumph

of the Washington State 1916 Rose Bowl Team (2015) The game of college football was ruled by the mighty and the powerful.

Standing among the best was the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, a team that relied on brute force to bully its way through the competition. The Cadets had a storied tradition of playing so aggressively that it was not uncommon for opponents to land in the hospital. The academy itself was built around the simple premise of training leaders for war.

But on this blustery day in November, thoughts of armed conflict were set aside for a heavily-anticipated game of football–a contest between two of the season's best. This one would be settled under gray skies before a crowd of over 5,000 fans in the stadium nestled near the Hudson River, where cool temperatures triggered a heavy gray mist that drifted onto the field.

The West Point Cadets, with only one loss on the 1912 season, were the team to beat. They were led by Capt. Leland Devore, a behemoth of a man, 6'6" with 250 pounds of sheer muscle. Standing next to him was a bruiser named Alexander Weyland, a heavyweight with a pounding style. Lined up, shoulder-to-shoulder the pair formed the point of a wedge that simply drove their opponents back. Much was made of their style of play the year before when two Yale players were hospitalized and nearly killed trying to stand directly in their way. In the backfield was running back and future Army general, Dwight Eisenhower. At only 5'8", this blonde-haired, blue-eyed character may have stood shorter than his larger teammates, but he carried with him a fierce determination. As a two-way player, he would lead the running game on offense, while racking up the most tackles on the team as a linebacker on defense.

L-R: Dwight Eisenhower, Jim Thorpe, Gus Welch, Pop Warner Facing them on this heavily anticipated day would be the Carlisle Indian School from Pennsylvania, a dynamic team with one of the best records in the nation on the season at 10-0-1. The college included Native Americans from 140 tribes from across the country. Using speed and an unorthodox style, the team had risen through the ranks by deploying new formations and uncanny deceptive style in the backfield. At the core of the Carlisle charge stood Jim Thorpe, arguably one of the greatest athletes of his day having just won two Olympic Gold Medals in the decathlon and pentathlon. He wasn't alone. QB Gus Welch was blessed with a slight-of-hand that brilliantly confused defenders. In a signature style, Welch would call out a play by muttering just a few words, or by using hand gestures and snapping the ball before the defense had a chance to get set.

Despite the racial tensions of the era, this Carlisle team carried a true swagger on the field, often taunting opposing players and making funny remarks as the game progressed. After one play where the referee gave Carlisle a bad spot with the ball, one player remarked, "What's the use of crying about a few inches when the white man has taken the whole country?" In another contest, with their opponent's defense left exhausted from the constant speedy barrage Welch taunted defenders by declaring, "We're going to run the ball to the right." They did and despite the warning of their intentions gained 20 yards. Carlisle's style of play led the nation in scoring, marching its way past East Coast dynasties such as Syracuse, Georgetown, and Pittsburgh.

Leading the way on the Carlisle sideline stood Coach "Pop" Warner, a grumpy curmudgeon of a man who often paced up and down the sidellines with a hand-rolled lit cigarette dangling from his mouth. The 42-year-old coach had long waited for this game. Despite his disheveled appearance, Warner was at heart a brilliant tactician. On this day, he had a few surprises in store for the Army team.

It had been Warner himself who had once dismissed Jim Thorpe for not being adequate enough to play football. When Thorpe first showed up at Carlisle, he was just another gangly kid in overalls. One day, walking casually across the athletic field Thorpe ran up to the school's high-jump bar and cleared it with ease. Other track athletes could only stand by in awe. Thorpe had just cleared 5'3", a height that would have been a school record. When word of the jump reached Warner, the coach reached out to Thorpe to turn out for track. The 18-year-old Thorpe had recently lost his father, so with the promise of playing sports and the fatherly approach of Warner, Thorpe would be convinced to stay at Carlisle to finish his education.

As the Carlisle track coach, Warner knew Thorpe could be something special, and he trained him all the way through to the Olympics. But it was on the football field where Thorpe could really shine. An athletic specimen with amazing speed who could do it all–dodge opponents with a crafty ability to switch direction, or power his way through, carrying players 10 yards down the field–Thorpe could also pull up and throw the ball 60 yards, or kick it just as far. But in the beginning, Warner did not want the boy to play football. "I'm sorry, son, but you're just not big enough." Pointing to players getting ready to practice, Thorpe gestured for Warner to give him the ball, saying, "Oh, c'mon, coach; you have to give me a chance." Reluctantly Warner agreed. The drill involved trying to weave through some three dozen players on the field. Thorpe took off like a jackrabbit, running left, then stopping short, and quickly shooting off in the other direction. Running virtually untouched, Thorpe continued on until most of the players gave up out of exhaustion. Rambling back up the sidelines, he tossed Warner the ball, saying, "I gave them some good practice, didn't I, Pop?" Warner just stood there amazed. He had no choice but to let Thorpe on the team.

But to Coach Warner on this day in November at West Point, something was not quite right with his usually brash team. Walking into the locker room, he found his 22 men huddled together, quiet and sullen. Only Jim Thorpe was standing, and nervously pacing around the wooden benches. Time was running out just before kick-off. Warner wasn't one for big speeches but looking into his players' eyes, he knew they needed something that would help them stand for themselves–something to set aside the fear of playing against the U.S. Army.

Stepping before them with a fierce look of determination Warner spoke, "On every play, I want all of you to remember one thing: your fathers and your grandfathers are the ones who fought their fathers. These men playing against you today are soldiers. They are the Long Knives. You are Indians. Tonight, we will know if you are warriors. Let's go!" With that the players leaped up in unison, heading outside with new determination.

Eisenhower himself had long awaited this contest, believing he would be the one to knock Thorpe from the game. Having won the toss, Carlisle would receive. The crowd roared as the high kick landed into the hands of Jim Thorpe on the 15-yard line. Racing up the middle, he would be brought down on the 30-yard line.

Warner had sent scouts ahead to watch the Cadets play, so he knew their favorite tactic was to push straight up the middle on defense. He had to smile. His team had been working on a new formation for weeks, just for this moment. As Warner's boys lined up, QB Gus Welch called out the first audible, causing the backs to split out to both sides. It would be football's first double-wing formation, one that Warner had devised just for this contest. His plan was to neutralize Army's strength by buttoning it up from the outside. The wings, near the line of scrimmage, would effectively seal in the outside tackles. This formation also multiplied the number of options available to the team for sweeps, reverses, or any number of pitches or passes.

L-R: Alex Arcasa, Stansil Powell, Joe Guyon On the very first play, Carlisle QB Welch pitched the ball out to HB Alex Arcasa, who sprinted from right to left for 15y behind the blocking of Thorpe. No sooner was he down than the team sprinted back into formation without pausing to huddle. With the same formation, another wide pitch was open to Arcasa, running to the right. Suddenly, the back stopped, looked left, and threw the ball to the other side of the field to Thorpe for a 15y gain. Just like that, Carlisle had moved the ball into Army territory for a first down, a feat few teams had accomplished that season.

Three plays later, Carlisle used the same play. As Army chased Arcasa to the right, he pulled up and passed again to Thorpe, who was out in the open field. This time, Army LB Dwight Eisenhower was ready. Taking a bead on the speedy runner, Eisenhower saw his chance and put a huge hit on Thorpe. He was't alone. From the other side, a second Army player reached Thorpe at the exact same moment. The massive collision could be heard from the stands. Thorpe was stunned and lost the ball. Army would recover deep in its own territory.

As the play cleared, Warner's heart sank. There lay Jim Thorpe, rolling on the ground in pain, holding his right shoulder. The Army tradition of trying to knock a man out of the game appeared to have worked. Warner and others raced to Thorpe's side. The first thing the coach did was to feel along Thorpe's shoulder blade to see whether there were any breaks. There weren't. The referee pointed to his watch and said, "Coach, we'll need to move him on a stretcher."

"Hell's bells, Mr. Referee," said Lenox, the Army Captain, "let's give him all the time he needs."

It was in that singular moment that everything changed.

Thorpe jumped to his feet as if nothing had happened and ran to the sideline, lightly rubbing his shoulder. The attempt by the Army captain to be gracious appeared to have struck Thorpe as condescending. From that point on, Thorpe played with a heightened sense of determination. Angered by what had happened, Carlisle FB Stancil "Possum" Powell punched the Army QB Vern Pritchard. Powell was ejected from the game and the penalty gave Army the ball at the Indians' 25-yard line.

The Cadets lined up for their power style of play. Briefly, it seemed Carlisle's defense might hold. The defenders rarely stayed still before the snap, which gave the Army offense trouble in figuring out just whom they were supposed to block. But Army answered by switching to a tight, sweeping formation. A powerful flow of men followed by RB Eisenhower eagerly flattened any defender along the way. In just a few plays, Army had its first down on the Carlisle 15-yard line. Almost with ease, Eisenhower again took the ball and followed his blockers around the right side untouched, marching deftly into the end zone. Army took an early 6-0 lead, a botched extra point attempt the only mark against a flawless drive. The sound of cannon rocked the stadium from the south end zone. Fans celebrated in the stands, believing the game was well in hand. With little emotion, the Army players simply dusted themselves off and lined up to kick.

Unlike most teams of the day, Carlisle used completely different players for offense and defense giving Warner a freshly rested team for each change of possession. On offense, the full force of Warner's coaching chicanery came into views. Sweeps suddenly turned into reverses. Grand gestures to take the ball into the line left defenders rushing forward to make a tackle on players who suddenly didn't have the ball. A simple pitch by QB Welch to Arcasa sprinting to the right became a reverse to a sprinting Thorpe going left. When Army seemed to have the runner corralled in the backfield, Carlisle would suddenly stop and throw the ball deep downfield. Play after play, the offense appeared to be performing a well-rehearsed ballet. Soon, Carlisle found itself on the Army eight. The drive would end as strangely as it had begun: a trick play where the center snapped the ball, dropped back to block, then while the backs took off in both directions, QB Welch faked left, then right, then quietly handed the ball to his blocking center, who charged up the middle for an easy score. With the extra point, it was now Carlisle in the lead 7-6. Fans grew silent at this sudden change.

When the Carlisle defense returned to the field, its players resumed their constantly moving style of play, using their speed and agility to maneuver around the power blocking attack. Defenders stepped away from powerful blocks only to nip at the runing backs from the side. Army could still move the ball, but it could only manage a few yards at a time. Suddenly, Army found itself failing to make a first down. Carlisle would take a one-point lead into halftime.

In the locker room, the Army players were frustrated with their performance. Eisenhower pulled aside his fellow linebackers to make plans to "take out" Thorpe. Fans often referred to it as "the ol' one-two," with one player striking up high in the chest, the other taking out the legs.

Thorpe seemed stronger in the second half than in the first. On the team's first possession, Thorpe sprinted from side to side, knocking defenders to the ground with a devastating stiff arm. When it seemed Army had Thorpe cornered, he would suddenly pull up and throw the ball deep with surprising accuracy. When he didn't have the ball, he proved to be a devastating blocker. With his team lined up near the end zone, Thorpe and Joe Guyon doubled up on Army's leading tackler, Leland Devore with a surprisingly powerful blow. Right behind them, RB Arcasa all but strolled into the end zone, giving his team a 14-6 lead.

The block left Devore enraged. On the ensuing kickoff, he appeared to take his frustrations out by rushing full speed into Carlisle's Guyon, who never saw the blow coming. Devore's hit drove the smaller player to the ground and left him unconscious. Pandemonium threatened to take over the game as emotions now ran high. After a brief huddle, the referees ejected Devore for "unsportsmanlike conduct." Eisenhower knew that without his best blocker and best defender, the game would be on his shoulders. His plan to take out Thorpe seemed even more critical to the outcome. After three plays, Army was forced to punt. With Carlisle back on offense, Ike would have his chance.

Nearly everyone knew that on first down, Thorpe would get the ball. On the snap, Walsh spun around to buy Thorpe a moment for his blockers to do their work. The Carlisle offense continued to weave in a series of confusing misdirection movements, timed to open up a hole in the middle of the Army line that Thorpe raced through at full speed. This was the moment Eisenhower and Hobbs had waited for. The two linebackers lowered their heads with a full burst of energy, smashing into Thorpe from two sides. Eisenhower would later say it was among the hardest hits he had ever delivered. The collision could be heard from the top of the stands.

As the whistle sounded, players moved back to reveal all three men lying face down on the ground. Thorpe appeared to have taken the brunt of the punishment. For the moment, it appeared Eisenhower and Hobbs had won; they had just take down the greatest athlete of their time. But moment of victory quickly vanished as Thorpe jumped to his feet and ran back behind the line as if nothing had happened. The other two men were slow to get up.

A few plays later, Thorpe sprinted straight into the heart of the Army defense once again. Head down, he knew the punishment headed his way. Eisenhower eagerly raced forward to finish the job. This time, it would be Ike's teammate, Charles Benedict, who flew into the melee. All three barreled straight toward each other in a repeat of the exact same collision. Eisenhower couldn't believe he was getting a second chance. With even more determination than before, he propelled himself toward the sprinting Thorpe.

Yet at the very instant the trio would collide, something changed. Thorpe went from a full-speed run into an immediate stop. The Army linebackers already committed to a violent collision, slammed directly into each other with a tremendous force. Thorpe, with an almost comical gesture, stopped, and then cut around the pair for another substantial gain. Tossing the ball back to the referee, he glanced back to see the two Army linebackers writhing on the ground, dazed and nearly unconscious. As Eisenhower regained his senses, he tried to stand only to feel a shooting pain ripping through his right knee. Benedict stumbled over to the sidelines. Eisenhower tried to stay in the game but on the very next play, he would be removed by the Army coach.

With the power trio from Army off the field, Thorpe played the game of his life–at one point twisting into the air to snag a pass from Welch that was well over his head. Another touchdown gave Carlisle a 21-6 lead. Eisenhower, with his leg wrapped in an ice bag could watch no more, and carrying his helmet, he wandered away from the field. When it was all over Carlisle would win the game 28-6. Sportswriters swarmed all around Thorpe, who had just run for over 200y against one of the nation's best teams. He was now raised to elite status among the most popular football athletes of his day. As for Dwight Eisenhower, the disappointment was crushing. His roommate and closest friend would write that he had "lost interest in life" and was content merely to exist until graduation set him free.

USC Caused Stanford to Play a Home Game in Berkeley

CalBear8 on californiagoldenblogs.com 3/25/2012

No, I am not making this up. In 1924, the actions of the University of Southern California resulted in the Stanford football team playing a home game at California Memorial Stadium. Against Utah. There were allegations of players being paid, a fired coach, canceled games, secret deals, a school suspended from the conference, recriminations, counter-recriminations, even Knute Rockne got involved! Think of it as a preview for "Pac-12 Gone Wild!" And it all somehow resulted in the Stanford varsity football team taking the field at Memorial Stadium in Berkeley on November 8, 1924–as the home team. If you join me after the jump, I will do my best to sort out the great Pacific Coast Conference scandal of 1924.

"A home game in BERKELEY?" Stanford's first-year head coach Glenn "Pop" Warner was surprised by this turn of events.

The Pacific Coast Conference ("PCC") was less than a decade old when the 1924 scandal erupted, and USC had only been a conference member for two seasons. The Conference had been founded in 1915 with California, Washington, Oregon, and Oregon State as the original members. Washington State joined two years later, followed by Stanford. In 1922, the conference agreed to accept two new members, USC and Idaho. By that time, USC had already been playing PCC teams for several years. California, for example, had played the Trojans regularly beginning in 1916, and had compiled a 4-0-1 record against them by 1921.

But shortly after USC joined the conference, rumors began circulating that USC was paying cash to recruits and not requiring players to be academically qualified students. Although the requirements for player eligibility were relatively minimal at that time, paying players and failing to enforce academic requirements were clear violations of the conference bylaws. By 1924, California and Stanford became convinced that the rumors were true. USC, of course, denied that it had engaged in any improper conduct. Trojan quarterback Chester Dolley claimed the the very idea that USC would pay players "was really a joke," not because it was against the rules, but "because the university didn't have a dime." But, as will be seen, USC's football team was far from broke, and actually had tens of thousands of dollars on hand to spend on achieving football success.

Regardless of USC's denials, California and Stanford decided that they needed to take action to stop what they believed to be cheating by the Trojans. On November 1, 1924 the Trojans were in Berkeley to play the Bears. Before the game, Cal officials met with USC officials and informed them that California and Stanford had jointly decided to sever all athletic relations with USC at the end of the football season. The Bears then beat the Trojans 7-0, USC's first loss of the season and Cal's sixth consecutive win over USC.

Exactly what evidence California and Stanford had is unknown, as no public statements were made, and the entire incident has remained largely shrouded in mystery. The 1926 Stanford Quad yearbook (writing after the dispute had been resolved and there was a desire for friendly relations between all the schools), explained the situation this way:

Although the actual considerations which led the Stanford and California athletic committees to make this move will probably never been made public, it is generally known that a certain laxity in standards, culminating in an unfortunate disqualification of one of the U.S.C. varsity players just prior to the California-U.S.C. game, had direct bearing on this action. USC expressed outrage at the actions of California and Stanford. The university and its coaches again protested their innocence and two days later, after a vote by its student body, USC decided that rather than wait until the end of the season, it would impose a preemptive boycott on the northern California schools. USC announced that it would not play the game against Stanford, which was scheduled for the following Saturday, November 8, in Los Angeles. USC's graduate manager, Gwynn Wilson, told Stanford officials, "If we are not good enough to play you in 1925, we are not going to play you in 1924."

The authors of Fight On!, a history of USC football, dismiss the entire incident as nothing more than "institutional arrogance" by California and Stanford.

[D]espite a full investigation of USC before it was admitted to the Pacific Coast Conference, it was reported that Stanford and California retained "a spirit of distrust and intimated frequently that they did not believe Southern California was maintaining high scholastic standards nor enforcing such eligibility rules as were they." This may have been the first public display of an institutional arrogance that led a later USC coach, John McKay, to refer to people from Stanford as "those snooty bastards." However, these USC historians do not discuss the substance of the allegations against the Trojans. They make no mention of the USC player who was disqualified immediately before the California game, nor of the allegations of payments to recruits. They simply claim that the northern California schools had a vendetta against USC, asserting: "Whether there was any truth to the allegations about USC's academic standards is immaterial–Stanford and Cal were determined to play hardball."

USC's last-minute cancellation of the game put Stanford in a bind. According to the 1926 Stanford Quad yearbook:

The Stanford-U.S.C. game was canceled by the action of the student body of the southern institution. . . . At the time of the break, Stanford's plans for the U.S.C. game had proceeded on a mammoth scale. Special trains had been chartered, an entire hotel rented, and an elaborate schedule of events planned in Los Angeles. Even more significantly, Stanford was in the middle of a great season, and having one less game on its schedule could have endangered its Rose Bowl hopes. Stanford scrambled to find a replacement game. According to the Stanford Quad, the school contacted all the schools in the Bay Area to see if they could schedule one of them to play the following Saturday. But no one was available. In fact, St. Mary's would have been willing to play Stanford, but USC got to them first, booking the Gaels as their replacement opponent for the November 8 game in Los Angeles. (To USC's shock, St. Mary's pulled off a 14-10 upset.) Finally, as unimaginable as this may seem to a modern football fan who is used to the detailed preparations made in advance of every game, Stanford obtained the agreement of the team from the University of Utah to take the long train trip to the Bay Area with only four days notice.

Now that an opponent had been secured, Stanford faced another dilemma: where to play? The Cal and Stanford freshmen teams were scheduled to play at Stanford Stadium on November 8. There were no professional football stadiums in existence for Stanford to use. But there was one large stadium in the Bay Area that was going to be unused that weekend. The University of California Golden Bears were traveling to Seattle to play Washington on November 8. California Memorial Stadium in Berkeley would be empty. Calls were made between Palo Alto and Berkeley, and it was agreed: the Stanford-Utah game would be played at Memorial Stadium, with Stanford as the home team.

Why the Cal-Stanford freshman game was not moved to Berkeley, leaving Stanford Stadium free for Stanford's varsity game, is unclear. Possibly Stanford believed that attendance at the hastily scheduled Utah game would be poor wherever it was played, since it was on a weekend when the varsity squad was supposed to have been on the road and many fans had already bought tickets for the popular freshman game (known as "the Little Big Game") in Palo Alto. And perhaps both schools felt that it would be too disruptive and confusing for fans both to schedule a new varsity game at Stanford and move the Cal-Stanford freshman game to Berkeley on only a few days notice. But, for whatever reason, the freshman game was not moved. Thus, on the afternoon of November 8, 1924 for the first and only time in history, the Stanford football team ran out onto the field at Memorial Stadium in Berkeley as the home team. They were, of course, attired in their bright red home uniforms. There is no record of whether anyone called for them to take off those red shirts.

The game itself was anti-climatic. Stanford was in the midst of what would prove to be an undefeated regular season (although California would hold them to a 20-20 tie in the Big Game), which would end with a loss to Notre Dame in the Rose Bowl. Utah was simply not up to Stanford's level of play, and the team was also no doubt tired by the last-minute train trip to Berkeley, and ill-prepared for a game against a powerful PCC team it had not expected to play that season. The final score was Stanford 30, Utah 0.

Because of the scandal and because of its last-minute cancellation of the Stanford game, USC was suspended from the Pacific Coast Conference. But during the off-season a series of private meetings were held between the officials of the various schools and, by the beginning of the 1925 season, the Trojans had been reinstated to the conference. As with the original allegations of cheating by USC, the terms under which the dispute was resolved are shrouded in secrecy. Whatever those terms were, California was not satisfied with them. Despite USC's reinstatement to the PCC, the Bears refused to play them in 1925. But by 1926, the entire dispute had been patched up, again on terms that were not made public. USC reappeared on California's 1926 football schedule, leaving 1925 as the only year between 1921 and the present when there was no Cal-USC game.

George Halas Stories

Hit & Tell: War Stories from the NFL's Wildest Players

Joseph Hession & Kevin Lynch (1995) Former Chicago Bears owner, coach and player George Halas, was well known for his frugality. It inspired former Bears player and coach Mike Ditka to joke, "He throws nickels around like they were manhole covers."

Halas' legendary cheapness dates back to the club's early years. At the 1933 East-West Shrine game, Halas was impressed by a 270-pound tackle named George Musso. He offered Musso $5 to travel to the Bears' training camp and a salary of $90 per game with one caveat: He had to make the team.

At camp that year Halas informed Musso that he was about to be cut. Musso, desperate to play pro ball, refused to leave and said he'd play for half of what Halas had offered. Halas agreed and cut Musso's salary to $45 per game.

Musso not ony made the team but went on to play both offensive and defensive tackle for 12 years in Chicago. He was All-Pro three times and was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1982.

Halas never intended to release Musso. He just wanted to save $45 per game.

L-R: George Halas, George Musso, Billy Wade Halas also knew how to motivate players with financial incentives. As the 1941 season was drawing to a close, the 8-1 Bears were tied for first place with the Green Bay Packers. They needed to beat the Philadelphia Eagles to keep pace.

After falling behind 14-0 in the first half, most of the Chicago players were prepared to listen to one of Halas' legendary halftime tongue-lashings. But instead of attacking the players, he took a more logical approach.

"He said, 'If you guys lose this game and they win the next two, you lose your chance to play for the world title,'" former Stanford All-American Hugh Gallarneau recalled. "'And that means you lose a chance for a playoff check which could amount to as much money as your season's salary!'

"That pep talk really made sense. We went out and scored 49 points in the second half to win 49-14."

The Bears then beat the New York Giants to win the NFL championship and collected that coveted playoff check.

The first time a dog disrupted a Chicago Bears game by dashing out of the Wrigley Field stands and onto the football field, QB Bill Wade didn't suspect a thing.

But during his five-year career with the Bears, Wade witnessed an unusually large number of canines running onto the field. They almost always appeared at pivotal points in a game, when the Bears needed to break an opponent's momentum. Over time Wade began to cast a suspicious eye toward head coach George Halas.

"No one knew where the dogs came from, but it usually happened at crucial times in the fourth quarter, especially when things were going bad for us," said Wade, who quarterbacked the Bears from 1961-65. "Everything would stop until the dogs were caught." ... Wade believes Halas may have orchestrated the doggie dashes to disrupt the opponent's momentum.

"I could never say he did or didn't do it," Wade said. "I could never prove it. But I always thought he did. You never knew what Coach Halas was going to do. He was a mischievous person and a wonderfully interesting person."

Wade remembers once being involved in an intense conversation with Halas on the sidelines during a home game when a critical call went against the Bears' defense. Not having seen the play, but suspecting that his team had received the raw end of the deal, Halas stormed onto the field and displayed his anger by performing a series of well-choreographed theatrics.

"He was shaking his fist and pretending to shout at the officials," Wade said, "except nothing was coming out of his mouth. He was just trying to incite the fans."

Bo on the Bear

Bo: Life, laughs, and lessons of a college football legend,

Bo Schembecher & Mitch Albom (1989) As long as we're talking about great ones, I should tell you a story about Paul "Bear" Bryant, whom many consider the best college coach ever. It's hard to argue. Bear was one of a kind. A man's man. An old-fashioned, knock-em-down, drag-em-out football coach. Everyone knows how he won more games than any coach in Division I college football. And everyone knows about the national championships he won, and players like George Blanda, Joe Namath, and Ken Stabler, who grew up under his wing.

But I got to know Bear in a different way. They say you never forget your first kiss or your first car? Well, you surely never forget the first time you coach alongside Bear Bryant. It was a hell of a thing.

L-R: Bear Bryant, Bo Schembechler, Tubby Raymond The year was 1972. The Coaches All-America Game, an all-star game which doesn't exist anymore. We played it in Lubbock, Texas, in July. Have you ever been to Lubbock, Texas, in July? You play at night just to avoid heat stroke.

Anyhow, Bear was head coach of the East, and I was his assistant, along with Tubby Raymond, from Delaware. We flew in about a week early. Now, as you can imagine, it's tough to get players in July. Who wants to risk injury and sunburn? But somehow the West team–coached by Chuck Fairbanks, then of Oklahoma–was loaded. They had all these great players from Southern Cal and Nebraska, including Jerry Tagge, the Huskers quarterback.

And we were at least ten men short.

"What are we going to do?" I asked Bear, who by this time was in his late fifties, a little wrinkled, but still the toughest looking son of a gun you'd ever see.

"Well, Bo," he said, in that deep, gravelly voice, "we got to get us some players. How many you got up there at Michigan that can play?"

"Plenty. But we're only supposed to have three guys from any one team."

"The heck with that," he said. "Get all you can."

We ended up with five Michigan guys. Bear brought Johnny Musso, his great running back, and a few others from Alabama.

It was all last minute, none of which seemed to faze Bear. He told me, "Bo, coach the offense." He told Tubby, "You coach the defense."

"And me," he said, "I'm gonna play golf."

And that's exactly what he did. Every day. Tubby and I would start practice and sooner or later, Bear would roll in wearing some fancy plaid golf shirt and golf shoes. But there was never a question who was head man. One afternoon, I called a meeting for the offense, and right in the middle, Joe Gilliam, the quarterback from Tennessee State (and later the Pittsburgh Steelers) lit up a cigarette. Now, if one of my Michigan players did that, he'd be kicked out the door. But these weren't my guys. So I went out in the hall where Bear was just wandering around.

"Hey," I said, "I want to tell you something. I'm not teaching football to any son of a gun smoking a cigarette."

L-R: Johnny Musso, Joe Gilliam, Lionel Antoine He looked at me and waved his hand. Without saying a word, he walked into that meeting.

"Hello, men," he said. They all straightened up. "I want to tell you something: we're here to play football. I don't care what you do when we're not playing football, but when you're in a meeting, or practicing, we'll do things the way they're supposed to be."

He paused for effect.

"And there ain't going to be no ... smoking ... in ... here. Now, Gilliam you get that cigarette out!"

That was the end of the smoking problem.

As the game drew closer, everyone figured we'd get killed. We still didn't have enough players. We were trying to get Lionel Antoine, the outstanding tackle from Southern Illinois. He was supposed to play, but he was married, and his baby was in the hospital at the time.

I called him every day in Chicago, hoping maybe he could make it down. Finally, on the morning of the game, I tried one last time.

"How's it going, Lionel?" I asked.

"Everything is fine, now," he said. "The baby's all right. But it's too late to play in the game, right?"

"Not really. We need you. We don't even have a tackle."

He was flattered. "Well, I don't see how I could–"

"Look, hold on there a minute." I went to Bear. I told him the kid could play, but he was up north.

"Tell him to get ready," Bear said. "I'll send a jet for him."

"What jet?"

"The university jet."

"Well, gee, can you get the jet at this late notice?"

"For God's sake, Bo. I bought the goddamn thing for them! I guess I can get it if I want it!"

Believe me when I tell you, Lionel was down there in a matter of hours. I scribbled a few plays on a piece of paper–"You block here, then you block here"–and we stuck him on the bus.

The weather was hot and sticky. Riding to the game, we saw one of those temperature signs at a bank: it read 101 degrees. Bear was wearing his traditional button-down shirt and checkered hat. We got to the field, and the first thing he said was, "Well, God damn! Look at that! Their bench is overe there in the shade and we're in the sun!"

He looked at me. "Bo, I want you to get some guys and carry all our benches to the other side. In the shade."

"OK, Bear," I said.

And we moved our whole team. Carried the benches across the playing field, to the same sideline as the West. Set up right next to them.

And you know what? Nobody asked us a single question. That was the power of Bear Bryant.

The game started. Early on, the West had to punt, and Ron Curl from Michigan State broke through and blocked it. We got the ball and quickly scored a touchdown. It was 7-0.

We kicked off. They didn't move. We got the ball. Went 80 yards and scored again. Now it was 14-0. Less than seven minutes had passed.

O. J. Simpson was on the sideline for ABC. He found Bear, who was just standing there, watching all this, not calling any plays. And O. J. said, "Coach, that was a great drive! You sure are moving that ball."

Bear said: "Uh, yeah, absolutely. We figure we can, uh, run on these guys. We are well prepared."

"Thanks, coach."

"Sure."

O. J. walked away. I glanced over at Bear and we both laughed and shook our heads.

At halftime, Tubby and I went over some plays. This was Bear's only suggestion: "Bo. The sun is down. You tell them to bring those benches over to the other side now."

"OK, Bear."

And we moved back across the field. And nobody said a word.

By the fourth quarter, we had rolled up a big score, 35-20, and time was running out. All of a sudden, Bear was standing next to me. I looked up.

"Well, come on, Bo," he said, "what are you waiting for? Ain't you gonna run my play?"

"His" play–the only one he suggested all week–was a trick play in which you toss the ball to the running back out of the I formation, and he runs left, then throws it back across field to the quarterback, who takes off down the sideline. If it works, it makes the defense look bad.

"Gee, coach," I said, "You run that play, you're really going to rub it in."

He glared at me with those thin, steel eyes. "So what?" he snarled. "It's only the goddamn All-Star game. What the hell. I want my play run!"

"OK, Bear," I said.

I called the play. Sure enough, it worked to perfection. Our quarterback, Paul Miller from North Carolina, was wide open and scampered all the way to the two-yard line. And Fairbanks was over there, across the field, screaming at me: "You son of a bitch, Bo! You no-account son of a bitch!"

So I opened my arms and said, "Wait a minute! I'm not the head coach! I didn't call that play."

He couldn't hear me. I hope by now he's forgiven me.

We punched it in for a touchdown and that was it. 42-20. After the game, Bear gave all the credit to Tubby and me. "These guys did all the coaching," he told the press. "And they did great. Bo, I'd like to take you back to Alabama with that offense. You did a job, man."

That night they had a buffet dinner for everyone. Tubby and I were standing in line, and all of a sudden, over in the corner, we heard that voice, as thick as mud: "Hey, Bo! Tubby! Come on over here! We're not gonna eat that crap! We won the game!"

"Men, I had a few steaks flown in. Sit down. We're gonna eat like champions." And they brought out these porterhouses that were the biggest things I ever saw. We sat there and ate until way after midnight with the old coach, just talking and laughing about the game. What a week. I wish every young coach could get a chance like that."

Capital Expectations

The Future Is Now: George Allen, Pro Football's Most Controversial Coach

William Gildea & Kenneth Turan (1972) Redskins owner Edward Bennett Williams hired George Allen in 1971 to resuscitate the Washington franchise, which had not made the postseason since 1945. Into the sports desert stepped Allen, who vowed to win now by attacking the Redskins' most urgent problem, their porous defense, which ranked last in its conference against the rush the year before and twelfth out of thirteen teams in overall performance.

"I intend to concentrate on defense where I will spend a majority of my time," Allen said in his first meeting with the Washington press. "Our whole thinking is to get the defense riled up. That will be my main goal. If there's the opportunity to get a solid football player, we'll trade." Whatever had to be done - obtaining players, increasing the number of coaches and scouts, buying land and building the training complex - Allen wanted to do it in one swoop and knew how to.

L-R: Edward Bennett Williams, George Allen "I'm impatient," he reflected, after the 1971 season. "I don't want to have to say we're going to win next year or the next year. Everything we do is designed to help us win now. I believe in the first year you take over a job, whether it's insurance or banking or whatever, you have to make the changes that are necessary. I think if you wait a year and don't make the changes you lose something with your employees in the organization." ...

Holding the traditional NFL theory that a winning team is built painstakingly through the college draft, many Washington fans grew alarmed at Allen's references to trading, charging that he would ruin the long-range future of the team. A few went so far as to sell their season tickets to friends.

Bending enough to concede that Allen's preference for tested players might not be such a radical idea, Oakland's moving force Al Davis allowed, "With twenty-six teams selecting, it may be impossible to build a champion through the draft." But not even such a forward thinker as Davis could feel comfortable with the Allen technique in its purest form, which is not simply trading draft choices but all the draft choices. "I don't think," Davis added, "you have to go as far as he does."

On the draft day shortly after he took over the Redskins, the day Allen proved to Washington he was a shaker and trader the likes of which had not been seen, the Allen philosophy was manifested by his determination to trade more draft choices still. Having already unloaded seven that day, Allen, the story goes, sought desperately to deal the Redskins' second-round pick, which somehow still remained in his possession.

As the club's turn to choose came up in the New York meeting room, Allen frantically worked the phones in the Redskins office trying to make a deal. At the last minute, St. Louis offered a receiver, Dave Williams, but former Cardinal coach Charley Winner, now an Allen aide, talked Allen out of it.

Desperate for guidance with the time allotted to draft a collegian expired, the Redskins representative in New York, unable to raise anyone on the open line to Washington, blurted, "Washington takes Cotton Speyrer." Just then Allen picked up the phone to inquire what had happened. Told that Cotton Speyrer, the receiver from Texas, belonged to the Redskins, a frustrated Allen sputtered, "Look, I don't want Sprayer, Spryer, or whatever his name is."

But Allen had him just the same, a real, live draft choice, and he made the best of it. Midway through training camp, he did what came naturally, trading him to Baltimore in a deal for a veteran receiver, Roy Jefferson. "The theory that I don't like draft choices is incorrect," Allen explained after his first Washington season. "We like certain draft choices, like firsts. I'm interested in firsts.

"The building procedure can work both ways. When I was an assistant with the Bears and when I was in Los Angeles, both times, we traded for draft choices and had three first-round picks in one year. We got Dick Butkus, Gale Sayers, and Steve DeLong with the Bears and Bob Klein, Larry Smith, and Jim Seymour for the Rams."

Hollywood Failed His Audition

The Genius: How Bill Walsh Reinvented Football and Created an NFL Dynasty, David Harris (2008)

In his second year as 49ers coach (1980), Walsh was trying to upgrade his squad through the draft and trades. He obtained TE Charle Young from the Eagles. "He may not have been the super performer he had been," Bill later rememberred, but "I was confident he would work well in our offensive scheme. He was still capable of playing well, and most important to us, he was a great leader."

Bill was intrigued by Henderson's skills and impressed by what they could do for the Niners' anemic defense. He was fast, strong, and incredibly agile, and Walsh would later say Hollywood knew more about his position than anyone he had ever seen play it. There were, however, rumors of substance abuse connected to Henderson which McVay checked out with the Dallas hierarchy. The Cowboys front office denied any truth to the rumors and described their oddball linebacker as "clean as a whistle."

Walsh ended up trading a fourth-round draft pick for Hollywood. And, at first, Bill was thrilled to have him. When he ran Henderson through drills, he was stunned at the man's physical ability. Bill had also spent several hours in phone conversations with the linebacker before the trade and found him intelligent and likable. After Henderson joined the Niners, Bill even took the unusual step of inviting him over to his house in Menlo Park for dinner. It was a pleasant evening, though Bill wondered about Henderson's bladder because he kept leaving the table to use the bathroom throughout the visit. Bill Walsh knew nothing about cocaine addiction at that point in his career, but Thomas Henderson would be his first hands-on lesson in the subject.

Walsh's disappointment with his acquisition began at training camp and quickly snowballed. The linebacker would play impressively for one day and then be sidelined for the next week with various ailments, ranging from impacted wisdom teeth to a sore neck to twinges in his hamstrings. Good as he was, Henderson was never on the field, and Bill began to lose his patience. As Walsh later learned, Henderson was spending a good deal of his time while recovering from his injuries snorting coke back in his dorm room or in the restroom between team meetings or out in his Mercedes Benz in the parking lot. "He'd come in every day like he was sick," one teammate remembered, "looking like he'd rubbed a powdered doughnut on his nose." Soon all the other players "knew he was over the edge," another recalled. "It was obvious and unfortunate."

Eventually even Bill caught on that something was seriously wrong and his great trade was going to have to be aborted. Walsh's problem was that the terms of the collective bargaining agreement between the NFL and the NFL Players Association forbade cutting a player when he was too injured to practice and Henderson was covered under the rules because of his various ailments. To get around it, Bill eventually resorted to subterfuge. After a practice one day, Walsh found Henderson, who had missed the workout, asleep on the locker-room floor, with guys stepping around him. When Bill woke Hollywood, asked if he was all right, and received an affirmative answer, the coach convinced him to get his pads on and come out on the field to help him with a defense he was considering for the next game. Henderson bought the story and Bill recruited several players to go out and practice with him. Then he had the team cameraman film Hollywood going through his drills in case he ever needed to prove his point with the union. The next day, Henderson was cut and Walsh was glad to wash his hands of him.

Giants Pick LT

Barca, Jerry. Big Blue Wrecking Crew: Smashmouth Football, a Little Bit of Crazy, and the '86 Super Bowl Champion New York Giants.

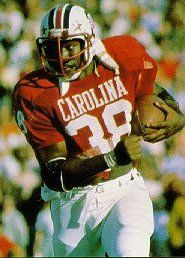

St. Martin's Press. Kindle Edition. The Saints had the #1 choice in the 1981 NFL draft, and the Giants had the second pick. On the weekend before the draft, staffers in the Giants' personnel department hit the phones. They dialed prospects to confirm the draft day locations and telephone numbers of the pro hopefuls. When they called Lawrence Taylor, he wasn't there. North Carolina's all-American defensive standout was in New Orleans. He was at the Saints' facility.

"Oh, shit. They're definitely going to take him," Jerry Shay, the Giants' chief scout said, recalling the collective reaction at the Meadowlands.

Bum Phillips, the former Houston Oilers head coach, had become the Saints' coach in the off-season. He made it clear he wanted to take George Rogers, the Heisman Trophy-winning running back from South Carolina. In Houston, Phillips had made the play-offs in his final three seasons, including two conference championship game appearances, and he built his success with the Oilers behind the powerful, bruising running of Earl Campbell. With the top collegiate running back available for the Saints, it was obvious Phillips would pick Rogers in an attempt to replicate the model of success the coach had with Campbell in Houston. The Giants' routine call to connect with Taylor cast doubt on that presumption.

"We thought we were going to have to take Rogers, which we would've been okay with, but we really wanted Lawrence. That scared the hell out of us," Shay said.

Once the draft order had been settled and the Giants had completed their scouting, the team figured it would get Rogers or Taylor. At that point, Shay put together highlight reels on each player. "Lawrence Taylor's highlight reel was a whole spool of a 16mm thing, and shoot, we had less than half a reel on George Rogers," Shay said.

Taylor wasn't the most decorated linebacker coming out of college. That was Hugh Green from Pittsburgh. Green finished second to Rogers in the Heisman balloting, the highest finish ever for a purely defensive player at that point. Green won the Maxwell Award as college football's most outstanding player, the United Press International Player of the Year honors, and the Lombardi Award as the top college lineman.

In his junior season, North Carolina changed how they utilized him. Taylor had been playing as a down lineman. They let him stand up. Rather than read and react to the play, Taylor went on the attack. He started to make plays, and he relished it. He became a force, and NFL scouts noticed.

"That's when his stock started going up," Shay said.

L-R: Lawrence Taylor, Bum Phillips, George Rogers, Hugh Green Midway through his senior season, opposing offenses constructed their game plans to avoid him. Oklahoma's head coach Barry Switzer called Taylor "Godzilla." Georgia Tech head coach Bill Curry said he "destroyed" the Yellow Jackets' offense.

North Carolina finished Taylor's senior season with an 11–1 record and ranked tenth in the Associated Press poll, the school's highest end-of-season ranking in more than three decades. Taylor was named the Atlantic Coast Conference Player of the Year.

Green had received more media attention, but pro football insiders had seen enough of Taylor to put him above the Pittsburgh linebacker.

"Lawrence Taylor was the only guy I knew at that size that could take a three hundred–pound guy and walk him back to the quarterback. Not only could he outrun him, he could outmuscle him, too," Shay said.

On the college level, Taylor played stand-up defensive end. In the pros, this translated to being an outside linebacker. The transition would prove to be more than ideal for the six-foot-three, 237-pounder with an unusual combination of speed and power.

Meanwhile, in the background, the Dallas Cowboys had been trying to work out a trade with the Saints for the number-one pick. Dallas wanted Taylor, and Taylor wanted to play for the Cowboys. Taylor was a fan of outspoken former Cowboys linebacker Thomas "Hollywood" Henderson. Taylor would eventually shift from his collegiate No. 98 to No. 56 in the pros because of Henderson, who, a few months before Taylor was drafted, admitted to having a $1,000-a-day cocaine habit.

With Dallas maneuvering for a trade to draft Taylor and the prized pick being at the Saints' facility in the weekend before the draft, the Giants already had two strikes against them. Then came a third.

New York's strongest position unit was the linebackers with Harry Carson, Brian Kelley, and Brad Van Pelt. Why draft another one? Plus, Taylor had retained Mike Trope as his agent. Trope had handled the rookie contracts for Heisman Trophy winners Earl Campbell and Tony Dorsett. Trope believed that high first-round picks should get three-year contracts worth $750,000.

Now, Giants players threatened to walk out if Taylor came in and surpassed them in salary before playing a snap of pro ball. "There's no way a rookie deserves to make more than some of us," one unnamed Giant told the Associated Press. Taylor heard about the comments and told the Giants' front office to back off. "I didn't want people to be mad at me. So I sent the Giants a telegram Monday saying I would rather not be drafted by them." That night, Giants players and coaches on the offensive and defensive sides of the ball called Taylor, assuring him there would be no issues.

Less than twenty-four hours later on April 28, 1981, the NFL draft commenced. Thirty-two seconds into the event, the New Orleans Saints picked Rogers. Phillips believed Rogers could do more than Taylor simply because you can give the ball to a running back. "He's a great linebacker, but if you put him on one side, they'd just run the other way the whole game. I couldn't get him in a position 30 times a game to make the big play," Phillips said.

Less than a minute after the Rogers pick, the Giants picked Taylor. Making fast picks was a calculated move by Giants general manager George Young. He believed it sent the message to other teams that the Giants knew what they were doing. Plus, if you had the guy you wanted, there wasn't any reason to wait to hear trade offers.

Across the Hudson River, in the draft room at Giants Stadium, Shay said there was a feeling of elation when they grabbed Taylor. But no hooting, hollering, and high-fiving. "That kind of stuff isn't allowed."

My Black Hat: A Gift from St. Ara

Jimmy Johnson as told to Ed Hinton: Turning the Thing Around: Pulling America's Team out of the Dumps and Myself Out of the Doghouse"

Johnson's first season as coach after replacing Howard Schnellenberger at Miami ended with a home game against Notre Dame.

As surely as Howard Schnellenberger's Orange Bowl upset of Nebraska had established Miami in the nation's mind as a football power, our game with Notre Dame would place a nationally perceived black hat on Miami's head, and specifically on mine.

Gerry Faust had run a legendary, super-power high school program at Moeller in Cincinnati. After Dan Devine resigned as head coach at Notre Dame following the 1980 season to go to the Green Bay Packers, Faust was named Notre Dame coach by the school's president in charge of athletics, the Rev. Edmund P. Joyce.

Faust's arrival in 1981 was the most celebrated for a Notre Dame coach since 1941, when Frank Leahy was brought in from a highly successful tenure at another Catholic school, Boston College. Faust was and is a devout man (and I respect that). So Faust's arrival was much more than a secular celebration. It was a nationwide religious experience. He was Mister Catholic. Sports Illustrated ran a picture of Faust kneeling at a little shrine, accompanied by some of his players.

L-R: Jimmy Johnson, Gerry Faust, Ara Parseghian, Brent Musberger It just never worked out like they'd hoped. Faust's years at Notre Dame were troubled indeed. In 1981 he coached the Irish to their first losing season since 1963 under Hugh Devore, who had only lasted that one season as head coach. In 1982, 1983, and 1984, Faust went 6-4, 7-5, and 7-5 respectively–this in a program whose followers were disappointed any year they weren't in the running for a national championship.

Here are some circumstances leading up to our game with Notre Dame on November 30, 1985, that I would not learn about until many years later, from journalists:

By the week of Notre Dame's final home game of the 1985 season, on November 23, against LSU, the Faust regime was coming apart at the seams, and deeply disillusioned Notre Dame players were beginning to speak out vehemently against Faust–they claimed he and his staff were inept and that the squad was simply miserable and fed up with him, except possibly for a few players to whom favoritism had been shown.

That week, there was a heavy undercurrent of feeling that Faust was about to resign under pressure, but Fathers Hesburgh and Joyce weren't confirming. Before the LSU game the Atlanta Constitution got some players to talk. With their stories of misery and incompetence came wryly spoken references to "Mister Catholic" and how, in crucial game situations, Faust would yell down the bench, "Okay! Everybody say a Hail Mary that we'll make this first down!" This on a staff which when offensive linemen would come off the field reporting that the blockiing scheme was futile and suggesting adjustments, would reply, "You do the playing and be quiet, and we'll do the coaching." And the onslaught from the opposing defensive front would continue.

The players who talked were adamant that the Constitution hold the story until the morning of the LSU game, to assure that they wouldn't be held out of their final home game in South Bend for speaking out. The story was picked up by CNN and South Bend was abuzz with it during the game, which Notre Dame lost to a mediocre LSU team, 10-7.

Notre Dame alumni in Atlanta wrote thankful and congratulatory notes to the Constitution, and added that they'd Fed-Exed the story straight to Father Joyce's desk, to make sure he got those kids' messages loud and clear.

The following week, Gerry Faust announced his resignation, effective after the last game of the season, which would be played on the road. That road trip, a nice one, amounted to one huge sigh of relief from the Notre Dame players. They wanted to go to Miami, to lie in the sun for a few days, after such a miserable season, and, in some cases, such miserable college careers.

And that was the Notre Dame team Miami faced on November 30, 1985. I knew that Faust had announced his resignation, but I had no idea of just how bad the situation was within the Notre Dame team. I'd been totally focused on coaching–we'd won nine games in a row–and hadn't picked up on the news stories.

In fact, getting ready for Notre Dame, I was scared to death. With the pride and the tradition of Notre Dame and the quality of their players, I thought Faust's resignation might be a rallying point for them. I could envision us walking into a buzzsaw, with them at a fever pitch emotionally to win one last game for Gerry.

Silly me.

On game week, the only hint that I had that they might not be ready to play was that a few of the media people had told us Notre Dame had come down a few days early and that their players were up in Fort Lauderdale having a big time enjoying the sunshine and the beaches.

Action in Miami's 1985 rout of Notre Dame Well, of all the games that I have ever coached in my career, I don't know that one of my teams has ever played another game as flawlessly as that Miami team did against Notre Dame. We scored on defense, we scored in the kicking game, we scored on every possession up until the last part of the game, and it was a complete rout, 58-7.

Now: Little did I know that with us playing so flawlessly and the rout being what it was, Ara Parseghian was up in the CBS broadcast booth almost in tears, saying that we didn't have any compassion.

Parseghian was there as color commentator. This was the same Ara Parseghian who'd spent eleven years as Notre Dame's head coach, 1964 through 1974, and who during that time had made a common practice of humiliating opponents. He coached so many routs that his mere over-40 totals would take too long to list, but here are highlights of Irish rampages on Parseghian's watch: On November 6, 1965, he beat Pittsburgh 69-13; on November 12, 1966, he beat Duke 64-0; on October 7, 1967 he beat Iowa 56-6; on October 19, 1968, he beat Illinois 58-8; in the 1970 season alone, he beat Army 51-10, Navy 56-7, Purdue 48-0 and Pittsburgh 46-14. And on December 1, 1973, he beat the University of Miami 44-0.

And Parseghian's ruthlessness was not at all a departure from Notre Dame tradition. Knute Rockne himself wasn't above hanging, oh, for example, a 74-0 on Kalamazoo here and a 77-0 on Beloit there.

And even poor old Gerry Faust hung a 52-6 on Purdue in 1983.

And never once, by November 30, 1985, had I criticized Notre Dame for running up a score. I still don't. Again: it's a 60-minute game. I just point out some of their routs to illustrate to you what an absolute hypocrite St. Ara the Tearful was being when he criticized me, saying emotionally to a national television audience, "It's time for Jimmy Johnson to show some compassion."

Well, even down on the sidelines, I guess I should have known. I'd learned way back in Port Arthur TX that nobody cries louder and more pitifully than a bully who's just had the shit stomped out of him. But later, when I watched the videotape of the telecast, I was incredulous.

Not only had Parseghian shown his gold underwear and been an obvious hypocrite to anyone with an objective knowledge of football history, but he had failed to do his job as color commentator, and Brett Musburger had failed to do his as a play-by-play man. They are there to spot with expert eyes and explain with expert tongues, things that the layman viewer has not spotted. One thing they said was absolutely ridiculous: "How can they [Miami] be blocking punts when the game is completely out of hand?" That was probably the line that made Miami a name that would live in infamy in Notre Dame hearts, and therefore in many, many American hearts in general. But here is exactly what happened on the punt block: By that point we had so many second- and third-string players in the game that we were having problems getting our substitutions straight. All the starters had been pulled. Notre Dame was punting out of their own end zone, and we set up to return the put, but it wasn't even our regular punt unit. We called for a return right. By no stretch of the imagination did we have a punt block called. And, in the substitution confusion, we only got ten men on the field for the play.

And then Bill Hawkins, one of our backup defensive tackles, strolled untouched into their backfield and blocked the punt for a touchdown. Now if we'd sent some first-string strong safety firing through a gap or around the outside to block the punt, that would have been one thing. But as it was, any junior high coach could have sat up there in the broadcast booth and seen that there was no punt block on and that Bill Hawkins had just waltzed in. What was Bill supposed to do? Take five giant steps backward and bow while the punter got it off?

And any color commentator or play-by-play man with anything remotely resembling an objective eye would have seen that and would have said so. But this was Parseghian and this was Notre Dame. Very few Amerian souls are objective about Notre Dame. Most people either love them or hate them, and the lovers vastly outnumber the haters. And to compound it, this was Gerry Faust's last game and everybody felt for him–everybody, it seems, except his players. Those players were truly just putting in time that day, and my team happened to play flawlessly.

I had never seen anything like the reaction we got the next week. We had stacks and stacks of letters, most of them negative. But some of them were very positive. "Hey, Notre Dame has been doing that to us for years. I'm glad you did what you did."

But that was the day Miami got the black hat, a gift from St. Ara, placed squarely on my head. And to this day a lot of people think I'm negative toward Notre Dame. Just the opposite is true. I've always had tremendous respect for Notre Dame, and actually, it's one of my favorite schools. It's just that we happened to put a score on them that they'd put on other people for years and years.

My Black Hat: A Gift from St. Ara

Jimmy Johnson as told to Ed Hinton: Turning the Thing Around: Pulling America's Team out of the Dumps and Myself Out of the Doghouse"

Johnson's first season as coach after replacing Howard Schnellenberger at Miami ended with a home game against Notre Dame.

As surely as Howard Schnellenberger's Orange Bowl upset of Nebraska had established Miami in the nation's mind as a football power, our game with Notre Dame would place a nationally perceived black hat on Miami's head, and specifically on mine.

Gerry Faust had run a legendary, super-power high school program at Moeller in Cincinnati. After Dan Devine resigned as head coach at Notre Dame following the 1980 season to go to the Green Bay Packers, Faust was named Notre Dame coach by the school's president in charge of athletics, the Rev. Edmund P. Joyce.

Faust's arrival in 1981 was the most celebrated for a Notre Dame coach since 1941, when Frank Leahy was brought in from a highly successful tenure at another Catholic school, Boston College. Faust was and is a devout man (and I respect that). So Faust's arrival was much more than a secular celebration. It was a nationwide religious experience. He was Mister Catholic. Sports Illustrated ran a picture of Faust kneeling at a little shrine, accompanied by some of his players.