|

Fists Flew When the 49ers Faced the Eagles

Joe Hession, Coffin Corner: The Official Magazine of the Professional Football Researchers Association (Volume 42 Number 5 2020)

Kezar Stadium, the San Francisco 49ers' original home field, was known for its notoriously rowdy football fans. They were out in full force for the 1953 season opener when a bench-clearing brawl erupted on the playing field.

Bill Mulligan, a veteran San Francisco Examiner scribe of the era, described the action in grandiose prose. "In 30 years of sports reporting and several youthful years as a spectator before that, this chronicler has never seen a Donnybrook in any sports arena to equal today's bigger and better brawl."

Bad blood had been stewing between head coach Buck Shaw's 49ers and Jim Trimble's Philadelphia Eagles since the opening kickoff. San Francisco LB Hardy "The Hatchet" Brown, known as the meanest man in football, lit the flame early by flatterning Eagles RB Toy Ledbetter with one of his infamous shoulder tackles. Ledbetter was helped to the sideline, then left the game with a broken cheekbone.

On the field, San Francisco built a hardy 24-7 lead behind QB Y.A. Tittle's superb offensive display. He fired an 18-yard scoring strike to speedy RB Joe Arenas in the first period, added a 1y touchdown plunge in the second quarter, and found receiver Billy Wilson in the end zone with a 38y pass in the third stanza.

L: 49ers (dark jerseys) vs Eagles 1953; R: Y. A. Tittle Late in the fourth quarter, tempers again flared on the field. This time Eagles receiver Bobby Walston exchanged shoves then punches with 49ers DE Charlie Powell. Walston picked the wrong man to tangle with. Powell was a highly acclaimed amateur fighter who spent his offseasons in the boxing ring taking lessons from light-heavyweight champion Archie Moore.

While Powell mauled Walston in the end zone, Hugh McElhenny, the NFL's 1952 Rookie of the Year, was attacked by a pair of helmet-swinging Eagles led by Pete Pihos. The sight of the 49ers Pro Bowl running back being blindsided by a pack of Philadelphia players was more than the Kezar Stadium crowd could handle. Already fired up by a steady flow of liquid refreshments, they swarmed the field in an effort to assist their hometown heroes.

In the 10-minute melee that ensued, 49ers players and fans battled together against the overmatched Eagles. Fists, bottles, helmets and cleats flew through the air. Hardy Brown tangled with Eagles RB Al Pollard. Philadelphia's All-Pro C Ken Farragut went after LB Clay Matthews. At least three separate skirmishes took place on different areas of the gridiron.

Game officials attempted to restore order and were unceremoniously trounced. Back judge Norm Duncan courageously waded into the thickest part of the fighting crowd. Seconds later he was seen crawling out of the pack, then being helped to the sideline.

Finally, Joe McTigue and the 49ers band tried placating the crowd with a rendition of the National Anthem. Unfortunately, several band members had used their clarinets and trombones as weapons and they were now useless as musical instruments. San Francisco police officers from Park Station, located adjacent to Kezar Stadium, were quickly summoned. They employed harsher tactices to bring the unruly mob under control.

In the aftermath of the brawl, Powell and Walston were ejected from the game. At least three 49ers - G Bruno Banducci, T Leo Nomellini and C Bill Johnson - sported black eyes. And the 49ers walked away with a 31-21 victory.

In retrospect the Eagles were foolish to pick a fight with the 49ers, who were well stocked with men itching to grapple. Besides Powell, the San Francisco roster included WWA wrestling champion Leo "The Lion" Nomellini, a World War II Marine combat veteran who wrestled in the off season as a "hobby." "Leo was strong as three bulls," Perry once said. "He'd slap you on the back and knock you 20'."

Even more dangerous was Hardy Brown. In the pre-facemask era, Brown routinely sent opposing players to the hospital with broken jaws, missing teeth and concussions. He was selected in an NFL poll as one of the "Ten Meanest Defensive Players" in league history. Gordy Soltau, a teammate of Brown for four years in San Francisco, recalled, "People shivered when you mentioned Hardy Brown. Nobody hit like him."

Best Coordinator Tandem Ever? - 1

Lombardi and Landry: How Two of Pro Football's Greatest Coaches Launched Their Legends and Changed the Game Forever, Ernie Palladino (2011)

Vince Lombardi was what today would be called the Offensive Coordinator for the New York Giants from 1954-58 and Tom Landry was the Defensive Coordinator 1954-59. The head coach was Jim Lee Howell. The Giants won the NFL Championship in '56 and lost in the championship game to the Baltimore Colts in '58.

In his first year with the Giants, Lombardi was almost universally disliked among the team's veterans ... Who did this big-mouthed guy think he was, full of bluster but devoid of any pro experience? Did he really think that rinky-dink Army offense was going to work? Gifford, who later became one of Lombardi's greatest friends, called him "loud and arrogant, a total pain in the ass." ...

Though the bombast continued, Lombardi adjusted. After some initial, failed attempts to gain their trust that first (training) camp, Lombardi visited some of his key players and asked for help. What plays did they like to run? What were they comfortable with?

"We would listen to him and he would listen to us," QB Charlie Conerly said.

He made accommodations to age and skill sets. He bent. And in return, the players gave him their loyalty and attention. Though he would become more aloof from the players as a head coach, with these Giants he drank, played cards, and communed as a human being. ...

Landry was a totally different personality. "Very quiet," said John Mara (the eldest son of Giants owner Wellington Mara). "Lombardi was not that way. Very gregarious. Talkative and loud. Two completely different personalities." ...

The one quality Landry and Lombardi did share was competitiveness. Be it football, golf, tiddlywinks, whatever, they both possessed an unquenchable desire to win. ...

When it came to football, the performance of the two coaches' individual units became their ultimate measuring stick. Each became a major pain in Howell's ear while promoting the offense or defense, lobbying for more time, more attention; a punt instead of an offensive play on fourth-and-short or, in one instance, a risky play instead of a field goal on fourth-and-10.

There, in keeping Landry and Lombardi on a peacefully even keel, Jim Lee Howell's true genius emerged. He wasn't a fantastic game coach. He wasn't a great strategist. He never garnered undying love from his players. But without a head man like Howell - a boss willing to hear out both sides but strong enough to break a tie knowing full well he'd bruise one of his assistants' egos - Lombardi and Landry might well have become football's version of the Hatfields and McCoys.

"Howell was smart enough to keep those two at bay," said Don Smith, the Giants PR Director. "He knew he had a good team there ... He'd keep the harmony so the two of them wouldn't be at each other's throats. He might suggest some things, like put this guy here, or do this on this play, but for the most part Lombardi and Landry ignored him." ...

When things went right with the offense, out came the jovial Vinny ... But when things went bad, a depressed, angry Vinny would take over. Landry hung the nickname "Mr. High-Low" on him "because when his offense did well, he was sky high; but, boy, when they didn't do well, you couldn't speak to him."

L-R: Tom Landry, Jim Lee Howell, Vince Lombardi, Frank Gifford, Charley Conerly Whether by loud, crude cajoling or calm explanation, both men were tremendous teachers. Different, certainly, but both extremely effective in his own manner.

"Tom never swore," Landry's star MLB Sam Huff said. "He always said, 'If you do what I tell you to do, we can control the game. Don't guess. You gotta believe in what I'm telling you,' and you did."

When things went wrong, it only took a mere glance from Landry to let the player know he'd sinned.

"He never screamed," Huff said. "It was just the way he looked at you. When Tom Landry looked at you, it was a stare. It was like, 'You know better than that.' He was a master teacher."

Wellington Mara likened them both to college professors in their blackboard presence. The only difference was that Landry's intellectual approach made it seem like he was teaching the top 10 percent of his class while Lombardi's earthier, repetitive method seemed directed at the bottom 10 percent.

As it happened, the Giants defenses under Landry became one of the league's most intelligent units, especially once cerebral players like Andy Robustelli, Harland Svare, and DB Jimmy Patton came aboard.

verywhere. He would stop practice to correct a player, or the entire unit, for failing to run plays correctly. No one was immune, be he Frank Gifford, Alex Webster, or any blocker.

Best Coordinator Tandem Ever? - 2

Lombardi and Landry: How Two of Pro Football's Greatest Coaches Launched Their Legends and Changed the Game Forever, Ernie Palladino (2011)

If it weren't for Paul Brown, there may never have been a Vince Lombardi or a Tom Landry. At least not a Lombardi or Landry who coached professional football franchises.

Like a mother raising children, Brown and his methods and strategies provided both men, in very different ways, their professional football compasses. ...

Brown knew the league as well as he knew his own team, and he recognized the head coaches and assistants who had true, forward-thinking philosophies. In Landry and Lombardi, he saw the two men who were truly responsible for the Giants' success. ...

Like so many nurturing mothers, Brown had his favorite son. The great Cleveland coach forged a lifelong relationship with Lombardi.

After Lombardi took the Green Bay job in '59, they often visited with each other, ate dinner together, swapped stories and player information. There were many late-night phone calls between the two. It helped that they were not in the same division or, eventually, in the same league, as Brown went off to the AFL's upstart Bengals in 1968 after a five-year absence following his firing from the Browns after the 1962 season.

"Lombardi and my father both had a good sense of humor, which people don't attribute to them," Mike Brown said. "They enjoyed telling stories like guys do." ...

And when it came to having Lombardi's back in the face of unwanted publicity, Brown became his closest ally. One story has it that long time New York Post reporter Leonard Schecter once wrote a profile of Lombardi for Esquire magazine that was so harsh - it compared his treatment of players to a general's ruthless use of troops in battle - it nearly drove the Packers' leader out of coaching. When Schecter showed up at Cleveland's training camp to do a story on Brown, the coach recognized him during a media conference.

"Are you the one that wrote that story on my friend, Vince Lombardi?" Brown thundered.

"Yes," said Schecter.

"Get out!"

Brown never became close with Landry, however.

"In terms of personalities, Landry was a lot like Brown, though not quite as stiff and set in his ways," author Jack Cavanaugh said. "Landry was more flexible. Brown was a martinet. Brown was a tough coach and had a huge ego. Landry never had a big ego." ...

L-R: Otto Graham, Paul Brown, Andy Robustelli, Tom Landry, Dante Lavelli, Mac Speedie "Cleveland always was a well-conditioned team, methodical and precise, and almost perfect in what they did," Andy Robustelli said. "Play execution was their hallmark. They were never the toughest physical team, but being so precise and talented they didn't need to win on toughness."

Brown demanded excellence of his players both on and off the field. On the road, he made them wear business suits, a demand Lombardi would later mimic as he reversed the casual, anything-goes-but-winning culture of the Green Bay Packers.

The precision of his team's game day execution began on the practice field, where Brown dictated the smallest details, like the exact height he required players to raise their legs on leg-lifts during warm-ups. ...

He noticed everything. Even the earliest risers couldn't put one past Brown. Rams coach Joe Stydahar tried. Before the 1951 championship game against the Rams, Cleveland billeted at the Green Hotel in Pasadena and was practicing on a nearby open field when Brown noticed a couple of Rams scouts running reconnaissance for Stydahar. So Brown set his defense up in a six-man line and threw in a bunch of other twists to fill the scouts' notebooks.

It was all a ruse. Brown never used any of it in the game. The Rams eventually won 24-17 ... but it took them more than a half to sort out the real scheme. ...

Landry was a rookie in 1949 with the old New York Yankees of the AAFC. ... He began the season as most rookies do, as a backup. But an injury in the secondary turned him into a starter just as the much-feared Browns came up on the schedule. Cleveland QB Otto Graham saw the kid, raw with talent but basiclly clueless as to the vagaries of the Browns' offense. And the pass master showed no mercy, challenging Landry with both Dante Lavelli and Mac Speedie throughout the game. The two ends sliced and diced Landry, racking up more than 200 receiving yards between them.

Landry, duly chastened, swore then that such a humiliation would never occur again. Not to him.

"The primary lesson learned that day served as the very foundation of my philosophical approach to playing and coaching pro football," Landry said years later. "Any success I ever attained would require the utmost in preparation and knowledge. I couldn't wait and react to my opponent. I had to know what he was going to do before he did it." ...

"Coordinated defensive thinking didn't work against the Browns' great offense," Robustelli said. "Because the Browns were our chief rival in the conference, Landry had to develop his coordinated defense; we had to find a way to beat them before we could win any titles.

"Tom later said he had to match wits with Paul Brown, and in doing so, Brown forced him to become a better coach since Tom had to develop a system that neutralized everything Cleveland did so well."

Oh Sure, Absolutely

Frank Broyles, Hog Wild: The Autobiography of Frank Broyles(1979)

Broyles became head coach at Arkansas in 1958. Oh, but what a honeymoon, football-wise, we had that first spring and summer before reality set in. We recruited one of the greatest freshman teams in the school's history. I toured the state meeting the fans and overselling the winged-T. During my rounds of Razorback Club fish-frys that year, I discovered Arkansas catfish. Back in Georgia (where Broyles grew up and played for Georgia Tech), muddy-water catfish were throwaways. As soon as I tasted the Arkansas variety, I ate more catfish steaks at one sitting than you could believe. I'd be back there sampling all the time they were cooking. I literally ate so much I'd make myself sick.

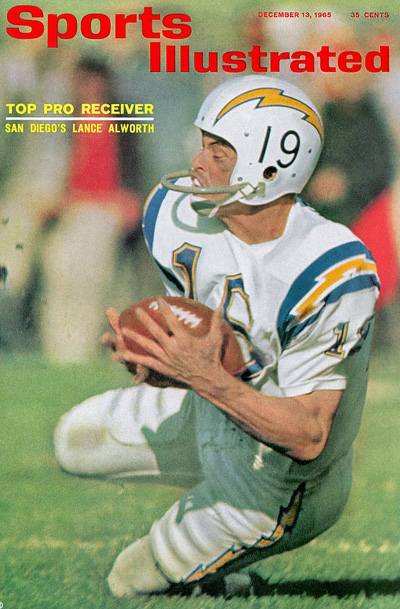

Elmer "B" Lindsey, a hot halfback from Forrest City, Jim's older brother, became the first athlete to "pledge" Arkansas for us, but a few weeks later, B signed a bonus baseball contract with the St. Louis Cardinals. About the time we knew we were losing Lindsey, we realized we might have a chance at Lance Alworth, an authentic national blue-chipper from Brookhaven, Mississippi. Lance signed early with Ole Miss (as most Mississippi blue-chippers did), but when he married his high school sweetheart he came up against Mississippi's no-marriage policy for scholarship football players. With an athlete of Alworth's potential, the school was willing to try to work around the rule. Lance could go to school on a baseball scholarship and go out for football, but his pride was stung and he didn't want to do that.

L-R: Barbara and Frank Broyles, Lance Alworth I pulled out all the stops. I'd never involved Barbara in recruiting before–and would only one time in the future–but I took her to Mississippi with me for a week. She visited Betty Alworth and her parents while I played golf with Lance and his father. We went on to Memphis where Lance was a prominent player in the high school All-Star game they used to hold there each summer. One night we were going to dinner, and Mr. Alworth said, "How about some seafood, Frank? I know a great place."

"Terrific," I said.

"I love raw oysters, Frank. How about you?"

"Oh, sure. Absolutely." (I could never bring myself to try to eat one before, but you can bet I wolfed 'em down that evening.)

They came to Fayetteville for a visit, and we were on the golf course when I first allowed myself to think that Lance was coming with us. He asked if it could be worked out so they could stay an extra day. Trying to restrain myself from jumping 12 feet in the air and giving a war whoop, I said, "Why, yes, I think that can be arranged withouot any problem."

Well, I'm sure you know Lance played on our three straight championship teams, 1959-60-61, and made All-American, and followed up as one of the all-time pass-catching stars in pro football. He gave our image a great lift before he even played a game. He represented a real breakthrough for us; Arkansas wasn't accustomed to going into neighboring states and coming away with national blue-chippers.

By this time, the Razorbacks pretty well had an edge on the recruiting of almost any Arkansas prospect. The state had closed its ranks around the program. Out-of-state recruiting usually meant finding a few playes in the Memphis area, or in parts of Missouri, Oklahoma, and Kansas, that were close to Fayetteville. It would be another year or two before we made any headway in Texas.

Lonely End

Strange But True Football Stories, Compiled by Zander Hollander (1967)

As Army went into the last game of the 1957 season, the Cadets appeared to be headed toward an extremely successful year. They had lost their third game of the season, a tough 23-21 defeat at the hands of a strong Notre Dame team, but five victories had followed. Then on that last Saturday, in Philadelphia's Municipal Stadium, more than 100,000 fans watched Navy beat Army, 14-0. The fact that Navy was Army's bitter rival made the defeat even more painful.

"That's the game you think about all winter," said Earl "Red" Blaik, the Army coach.

As a result of the defeat, Colonel Blaik set about devising a new offensive strategy. In 1958 Army would be strong again, but so would Navy. Blaik wanted to have a good season, of coure. But even more important, he wanted Army to avenge its loss.

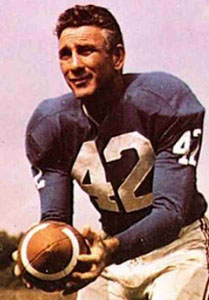

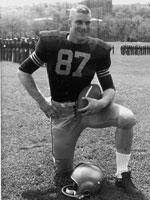

L-R: Bill Carpenter; Carpenter flanked far out to the right for Army. In Colonel Blaik's strategy one man played a crucial role. He was a previously undistinguished end named William Stanley Carpenter. As a sophomore in 1957, Carpenter had been injured and had seen action in just four games. Bob Anderson, an All-America halfback, and Pete Dawkins were the leaders of the team. In fact, not too many people outside of Carpenter's close friends knew that Bill was even on the team.

"He was a good cadet who liked the spit and polish of West Point life," Anderson said.

Besides being a diligent cadet, the 6-foot 2-inch, 205-pound Carpenter was a fine lacrosse player.

"I needed a player who was strong, smart and agile. Most of all he had to be able to handle the possible pressures," Colonel Blaik said.

On September 27, 1958, Blaik's new tactics were revealed for the first time. Army was playing South Carolina, a weak team, so the Cadets had a chance to experiment before the later, more important games.

Joe Caldwell, the Cadet quarterback, came on the field for the first play, and the offense lined up in front of him for the play call and the signal number. They bent down and listened to his call. But the spectators noticed something odd–one player wasn't in the huddle. He was 15 yards away from the huddle, his hands on his hips, his eyes glued to the movement of the Army quarterback.

The reporters in the press box at Army's Michie Stadium scanned their program. The detached player was number 87, end Bill Carpenter.

Throughout the game, by some mysterious method, Carpenter was able to follow the play, decide if it was a pass or run, and carry out his assignment without going near the huddle. His uncanny ability upset the South Carolina defense and served as a psychological weapon.

"ARMY USES LONELY END" headlined the newspaper the day after the Cadets overwhelmed South Carolina, 45-8. Under Blaik's leadership, Army went on to beat Penn State, Notre Dame and Virginia. Then Army was tied by Pittsburgh, 14-14. After that, in quick succession, Colgate, Rice and Villanova went down to defeat. And finally the Cadets gained their revenge on Navy for the 1957 loss.

Carpenter was the big story of the year. How did he get his signals? Who told him where to run on plays? What could the defense do to stop him?

His classmates at West Point kidded him about staying away from the huddle, suggesting that the real cause might be bad breath.

The "Lonely End," who wasn't really lonely at all with that amount of attention, was collecting fan mail by the sackful. "Most of it," he said, "came from girls. They all volunteered to be my friend. I even got some letters from Lonely Hearts clubs."

In January of 1959, Colonel Blaik, who was retiring from West Point, revealed the details of his Lonely End strategy at a dinner of the Touchdown Club of New York. He began by explaining the complicated signal system.

"Caldwell [the quarterback] signals Carpenter with his feet. Two feet together means a run; left out front, also a run; right foot out front, a pass. Carpenter then signals Caldwell by rubbing his nose of tugging on his helmet. That revealed where he should run."

The audience was shocked at the explanation.

"Simple, wasn't it?" said Blaik.

"It was so simple I should have thought of it," said Eddie Erdelatz, the Navy coach.

The secret of the Lonely End was out. All the opposing coaches knew what to watch for, and everyone imagined that Carpenter would have to come back into the huddle.

Bill Carpenter looks to the huddle and receives the next play call. In 1959, Dale Hall, a former Army quarterback, took over as head coach. The football coaches of other schools could scarcely wait for Army's first game, against Boston College.

With the first offensive play, Carpenter, now a senior and the team captain, moved out 15 yards. Surprisingly, he would play is solitary role again. But it was thought that since opposing teams knew how he got his signals, he would be easily stopped. Boston College failed to do so, however. In that game Carpenter caught nine passes for 140y and two touchdowns.

For the next six games, Carpenter caught passes, blocked, and led the team in yards gained. Then in the Villanova game, he suffered a dislocated shoulder. This meant he would probably be sitting on the bench for the game against Oklahoma. Instead, his shoulder was strapped to his body and he caught six passes for 67y as Army was defeated by a close 28-20. Carpenter ended his football career in the game against Navy. Although the Middies won, 43-12, they couldn't stop the Lonely End. He caught four passes for 93y and a touchdown.

In June of 1960, Carpenter graduated from West Point and the Lonely End era was over. He had been picked for every major All-America team and had established five pass-catching records. He had also been appointed a cadet battalion commander and had won a special award for "Inspirational Personal Courage" in athletcs. His old coach, Colonel Blaik, said, "Bill Carpenter has the mentality for doing the unusual. He will make a fine officer."

"Someday," predicted his teammate Bob Anderson, "Bill Carpenter will be Army Chief of Staff."

Six years later, in Vietnam, for the heroic rescue of the men under his command, Captain William Carpenter was awarded the Silver Star and recommended for the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Merger Problems

America's Game: The Epic Story of How Pro Football Captured a Nation,

Michael MacCambridge (2004) The NFL and AFL had finally agreed to merge.

There was one more matter left to be dealt with, and that was the task of convincing [New York] Representative Emanuel Celler and the House Judiciary Committee to approve the merger. As the fall wore on and the owners grew increasingly alarmed, it became clear that Celler had no intention of letting the legislation pass. At a hearing in the Rayburn House Office Building on October 11, 1966, Celler upbraided Rozelle ..., refusing to let the bill out of committee.

Rozelle, seeking a way to break the logjam, called his friend David Dixon to see if he knew a North Louisiana congressman on the committee. "For someone as sophisticated as Pete, he was rather naive when it came to politics," said Dixon. "The idea that any congressman from Louisiana was going to be able to change Emanuel Celler's mind about anything was ludicrous."

Dixon had a better idea. House Majority Leader Hale Boggs, who'd been a fraternity brother of Dixon's at Tulane, was seeking to regain some popularity after his vote in support of the civil rights bill caused his electoral majority to drop from 67 percent to 55 percent. Dixon sent his political adviser, David Kleck, up to Washington the next day, to impress upon the patrician Boggs, no sports fan, that it would help his cause to push the bill through, especially since doing so would virtually guarantee an NFL franchise in New Orleans.

The NFL had been eying New Orleans for its next franchise anyway. So a thinly veiled quid pro quo was offered - a franchise for New Orleans in exchange for the exemption [from the anti-trust laws] - and Boggs went into action, circumventing Celler by attaching S. 3817 to a budget bill sure to pass in both houses.

The final approval would come October 21. Walking up the stairs of the Rotunda, when the vote looked like a sure thing, Rozelle was his usual humble self. "Congressman Boggs, I don't know how I can ever thank you enough for this. This is a terrific thing you've done."

Boggs had been a veteran of Louisiana too long to let such transparent politesse go unremarked. "What do you mean you don't know how to thank me?" he said. "New Orleans gets an immediate franchise in the NFL."

"I'm going to do everything I can to make that happen," Rozelle assured him.

At that, Boggs stopped and turned on his heels, heading back to the committee room. "Well, we can always call off the vote while you -"

Rozelle took two giant strides after Boggs, turned him gently around and said, "It's a deal, Congressman. You'll get your franchise."

"If this doesn't work out," said the patrician Boggs, by now perturbed, "you will regret this for the rest of your fucking life."

It worked out, signed by another presidential football fan, Lyndon Baines Johnson, who'd taken to ordering highlight reels from NFL Films sent to the movie theater at the White House. The NFL and AFL got their merger and, a week later, New Orleans got its NFL franchise.

Pete Rozelle announces the awarding of an NFL franchise to New Orleans with Congressman Hale Boggs to his left and Governor John McKeithen at far right. A Typical Day at the Office

From "You're Okay, It's Just a Bruise": A Doctor's Sideline Secrets about Pro Football's Most Outrageous Team, Rob Huizenga, M.D. (1994) The Orange Bowl was rocking! I mean actually swaying on its foundation, as 75,151 Raider-hating Dolphin fanatics stomped their feet in unison and screamed, "Beat L.A.! Beat L.A.! Beat L.A.!"

Only nine seconds remained in the opening half. We were ahead by a couple of points, but now Miami had our battered defense backed up to the one-inch line. Coach Don Shula, Miami's stoic-faced leader, waved off his field goal team. It was December 11, 1984. The Dolphins were 12-1, this year's top AFC team, and Shula wanted to beat us - the defending world champion Los Angeles Raiders - in the worst way.

Bob Zeman, the Raiders' defensive coordinator, sent in the gap goal-line smash defense. Dolphin QB Dan Marino handed the ball to Woody Bennett. Bam! He was immediately bent backward and dropped by Raider heavies Matt Millen and Mike Davis. The gun sounded, ending the half. Our sideline jumped in celebration.

s the reenergized Raiders jogged off toward the locker room, I ran out on the field to check one of our LBs, who'd been stricken with a violent stomach flu. He'd started vomiting early last night, and by game time had been passing enough watery stool to qualify as a cholera patient.

"I feel like shit," he said as I threw an arm around his waist and helped him off the field.

quot;Are you light-headed?" I asked.

"That was two quarters ago, doc. I'm at the one-foot-in-the-coffin stage now."

"We'll pump in some intravenous fluids during half," I said. "And I'll tell Coach Zeman you're questionable for the rest of the game."

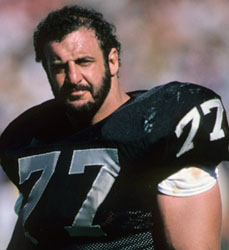

L: Lyle Alzado, R: Ted Hendricks Suddenly, just twenty yards from the visitors' locker room entrance, we were surrounded by an inebriated mob. The end-zone stands angled inward forcing us to run through a narrow alley. Red-faced, drunken Dolphin partisans - just a yard or two away from us on either side - were hurling profanities, peanuts, half-filled Cokes, and seat cushions.

Just to our right, one rowdy male fan in his mid-twenties caught Lyle Alzado right in the face with a full cup of beer, and then began to beat his chest in a drunken Tarzan impersonation. As we watched in horror, Lyle lunged over a four-foot retaining wall, grabbed the startled troublemaker's sweatshirt with one swat of his muddy left paw, and started beating the fan over the head with his helmet. Four of us rushed to grab Lyle's leg and pull him down, but he peeled us off with one torque of his hips.

Luckily, the foolhardy fan was able to stumble up several concrete stadium steps, out of Lyle's reach. Dazed and with blood dripping down his forehead, the fan was suddenly subdued. I wondered if he was sober enough to realize that he had come within a helmet hit of death.

Inside the locker room, the walking wounded congregated around four small examining tables in the cramped trainers' cubicle. It had the feel of a county emergency room on a Saturday night. My first priority was the LB. A trainer had already neatly set out a large-bore intravenous needle, intravenous tubing, and several plastic bags of a sterile sugar-salt solution. I quickly inserted one line in his right forearm while the assistant trainer rigged a bent hanger off an overhead pipe to act as a makeshift intravenous pole. I took his blood pressure lying down, then standing up. This maneuver caused the LB's blood pressure to drop, confirming dehydration as a cause of his dizziness.

"You're a couple of quarts low," I said. "Maybe even a gallon."

"Pump it into me, doc," he said. "I've got a game to catch."

Replacing several quarts of fluid in a ten-minute halftime is like changing a flat tire in ten seconds in the Indy 500 pits. It can be done, but it takes know-how and teamwork. ... Luckily all went well, and I was able to turn my attention to a receiver who had been patiently waiting behind me during all of this.

"My left eye's killing me, doc. I can catch a ball with one hand, but with one eye, I don't know."

"What happened," I asked.

quot;I think I got swiped during a tackle."

pulled out my medical kit and fished out a bottle of ophthalmic numbing solution ... With his pain relieved by numbing drops, I did a rudimentary eye exam. Standing on the other side of the room, I told him to close his good eye. I held up three fingers.

"How many fingers?" I asked.

quot;Is that how many fingers up or how many fingers folded down?" chimed in Dave Casper, who was sitting on a nearby table.

"Doc, get over here. Pull these pipes out. I gotta go."

"Wait! Halftime's not over for five more minutes," I replied.

"No, I gotta go!" the player said, pointing to his rear end and moving off the table, intravenous tubes and all.

The trainers and I quickly unhooked the hangers from the ceiling pipes and walked his double IV apparatus to the bathroom. The LB made it to the toilet. It was quite a sight. Two ball boys were perched atop the walls on either side of the toilet, manually squeezing the IV bags. I was pinched in between the toilet paper and the toilet bowl taking a sitting blood pressure. Then a defensive coach came by to go over the halftime changes in the defensive coverage schemes. All the while, diarrhea was hitting the bowl like a Malaysian monsoon.

As the player got up, I was faced with the final indignity of this halftime. Because I didn't want the player to bend his elbows, which might disturb the intravenous needles, he couldn't reach back and wipe himself. Enter teamwork. I obligingly wiped the patient clean after I took some stool to test for the presence of blood.

"Doc," said one of the trainers, who was standing on the adjacent toilet and looking over the stall, "if they could only see you now back at Harvard." ...

The security guard at the door signaled it was time to go back out on the field, but Ted Hendricks, one tough SOB and a future Hall of Famer who had just retired the year before, stepped forward to say something to the team.

"You motherf-----ers," he said, "don't embarrass me in my hometown. Get out there and hit somebody."

To demonstrate, he rammed his head into one of the metal lockers. It buckled inward. The team was hushed for a moment, half expecting his eyes to roll back or blood to gush from his mouth.

Instead he said in a psychotic snarl, "Take no prisoners ...!"

I went over to help the LB slip on his shoulder pads and jersey.

"Gee, I can't believe it," he said. "I actually feel good."

"We call this the instant man syndrome," I said. "Like instant rice. Take a pruned player, pour in a few liters of salt water, and puff! - instant man."

"Doc, you're sure these pills'll stop ..." he began.

He was worried about an uncontrolled burst of diarrhea in front of twenty or thirty million prime-time viewers, and I assured him that the three Lomotils I had just given him would prevent that from happening.

"You know, sometimes you bear down and strain when you make a hit," he growled. "I'm warning you ... if I get any brown stuff on the bottom of my uniform, you're fired as my doctor."

Prelude to the '85 Bears

Delsohn, Steve. Da Bears! Crown (2010)

Aggression was a weapon which Mike Ditka believed in. During the 1960s, he had been a relentless tight end for the Chicago Bears. Now, at age 45, he was in his third year as their combative head coach. Thus he viewed the next football game as more than a game. It was a litmus test to see just how ferocious his 1984 Bears were.

"If you want to defeat your opponent, you got to out-hit him," says Ditka. "People say, 'Well, you need to out-think him.' No! You gotta out-hit him. That's what football players understand. It's like a boxer. You hit him in the nose enough times he's gonna respect you. The Raiders were always a physical football team, and that's what we talked about before the game. I said, 'We're going toe to toe with these guys. It's gonna be a heavyweight match, and we're gonna slug with them.' "

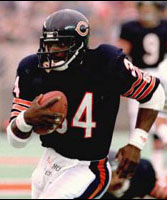

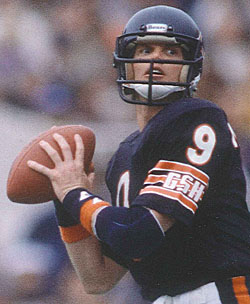

On November 6, 1984, the Bears mauled the Raiders 17–6. This being Chicago, it was windy and cold on that Sunday afternoon at Soldier Field. This being the 1984 Bears, the offense did just enough, led by its beloved warrior Walter Payton, who gained 111 yards and scored both of his team's two touchdowns. On defense, the Bears made the Raiders look weak and confused, forcing 3 interceptions and 2 fumbles and sacking the Raider quarterbacks 9 times. Read that again—9 times—because it doesn't happen too often. The single-game NFL record is 12, which is held by five different teams, including the '84 Bears, who did it later that season against the Lions.

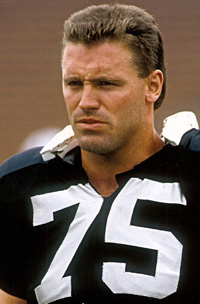

L-R: Mike Ditka, Walter Payton, Marc Wilson, David Humm Against the Raiders, it seemed as if the Bears competed against each other to see who could beat the snot out of the quarterback first. First they fractured Marc Wilson's arm and knocked him out of the game. Then they knocked out his replacement, David Humm, with a knee injury. Wilson was forced to reenter the game and found himself getting knocked out a second time. Curry Kirkpatrick, writing for Sports Illustrated during his heyday, was deeply impressed. "So brutal was the Bear onslaught that Al Davis was seen covering his face with his hands. Just breathe, baby."

The NFL's closest observers were also starting to see that the Bear offensive line had become increasingly nasty in its own right. Kurt Becker started that game at right guard for Chicago. A six-foot-five, 280-pound Michigan graduate with a maniacal streak, he frequently tangled that Sunday with future Hall of Fame lineman Howie Long, who later told Sports Illustrated he finally screamed at Becker, "I'm going to get you in the parking lot after the game and beat you up in front of your family!"

Becker says Long tried to follow through on his threat. "Howie was out of his mind by the end of the game," he recalls. "He tried to come into our locker room and confront me. Then he wouldn't get on their team bus. He was looking for me in the parking lot."

Years later, Emery Moorehead, Chicago's multitalented tight end, ran into the great Raider running back Marcus Allen, and they began reminiscing about the day the '84 Bears made the '84 Raiders look soft.

"Marcus said, after we knocked out both of their quarterbacks, they wanted to put in Ray Guy, their punter, because he was supposed to be their emergency quarterback," says Moorehead. "But Guy refused to go in. Then all of them were arguing at halftime about who was going back in—was it gonna be David Humm or Marc Wilson? Nobody wanted to go back in. That's how intimidating our defense was then. You can't even hit guys today the way our defense hit them. You'd be suspended."

Ditka, who doesn't joke about this kind of thing, says the 1984 win against the Raiders "was the most brutal football game I've ever watched. Did you see how many guys they were carrying off the field for both teams?"

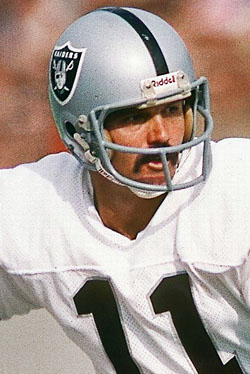

L-R: Kurt Becker, Howie Long, Ray Guy, Jim McMahon In the second quarter, the Bears lost their own starting quarterback, Jim McMahon, when he scrambled away from the pressure and ran for a first down before getting pinned between two Raiders. On the CBS telecast it looked fairly benign, but in reality one of the Raiders had struck McMahon in his side with a helmet. His offensive teammates told him to leave the game. He refused and remained for three more plays, but at halftime he had trouble breathing. McMahon tried to play again in the third quarter, and this time his offensive linemen ordered him to the sideline.

"Jim got hit in the kidney, and it came over the bone in his rib cage and his kidney got lacerated," says McMahon's longtime agent Steve Zucker. "I was in the stands, and I met him in the locker room. He was pissing blood, I mean pure blood, and he was in intense pain. He was in agony."

Adds McMahon, "They wanted to remove it, but I knew my career would be over. The bottom part of it was gone, and it was cut in about five places. It was bleeding for two days. The doctor told me, 'Look, you're gonna die if we don't cut it out.' I said, 'You can't cut this out, you cut it out and I'm finished. Just keep giving me the morphine and leave me alone.'

McMahon spent the next ten days in the hospital. Right after the Raiders game, Bears trainer Fred Cato told reporters, "At this point, I will say he will play again this season. But he will miss four weeks. There was no rib damage, no other organs were injured, but there was a lot of pain, and he did urinate blood. On the positive side, he didn't rupture the kidney, which could have ended his career." Cato turned out to be wrong about McMahon returning after a month. For McMahon, the '84 season had just ended. And just that abruptly the Bears lost their momentum. They were 7–3, but now it seemed less likely that they would keep winning enough to make the playoffs. If they did qualify for the postseason, their quarterbacks would be Steve Fuller and Rusty Lisch.

Jersey's Native Son

The Big 50: The Men and Moments That Made the New York Giants: Patricia Traina (2020)

In 1983, Bill Parcells thought he was ready to be an NFL head coach. Then reality set in.

Born August 22, 1941, in Englewood NJ, Parcells originally joined Ray Perkins' Giants staff in 1979 as the team's linebackers coach. He'd last only one season, moving to New England the following year to be their linebackers coach before returning to the Giants in 1981 to be Perkins' linebackers coach and defensive coordinator.

He didn't disappoint. The Giants defense finished 1981 with the third-best unit (yards allowed and points against) and the seventh-best unit in 1982 (yards allowed) and eighth-best unit (points against) as Giants reshaped their defensive image into a competitive, disciplined team.

In 1983, the Giants defense, and in particular the linebackers who considered Parcells another one of the guys, learned they'd have to share him with the rest of the team when the New Jersey native was named the new head coach following the resignation of Perkins.

At first, the defensive players weren't happy. Parcells, they said, was one of them, an honorary member. But sometimes when you care enough about one of yours as the Giants members of the defense did about Parcells, you have to let go.

"Once he became the head coach, we realized we had to take a different approach because if we continued to refer to him as 'our guy, our position coach,' we were concerned that the other guys wouldn't necessarily have the respect for him," LB Harry Carson said.

"So we adjusted to him as the head man, and we were able to sort of work together to get certain things done."

L-R: Bill Parcells, Ray Perkins, Harry Carson, George Young It wasn't easy. Parcells had been "one of the guys" as the Giants' linebackers coach and, later defensive coordinator, and despite his success in those roles, his first year as head coach was a disaster. Besides the 3-12-1 record, Parcells lost both of his parents that season, leaving general manager George Young to wonder if the weight of everything overwhelmed Parcells. Young was also intrigued by veteran college coach (and good friend) Howard Schnellenberger, whom he considered as a potential replacement for Parcells.

Utlimately, Young decided against making a change. But Parcells' near demise caused him to reevaluate his approach to his still-new role as a head coach and make some key changes.

One of the first changes he made was to detach himself from any personal feelings he might have had for his defensive players, and, in particular, his linebackers.

Parcells always had an eye for talent, but he and Young didn't always see eye-to-eye regarding personnel. But after the 1983 season, they did agree to move on from linebackers Brian Kelley and Brad Van Pelt, one half of the famed "Crunch Bunch" that also consisted of Carson and Lawrence Taylor.

The Giants would add LBs Carl Banks and Gary Reasons, the team's first- and fourth-round picks in the 1984 draft and two players who would become staples, along with Carson and Taylor, in that great Giants defense of the 1980s.

L-R: Brian Kelley, Brad Van Pelt, Lawrence Taylor, Carl Banks Parcells also went from being a mild-mannered, sweetheart of a guy to a wise-cracking, sometimes cantankerous man who was far less forgiving of mistakes players made to beat themselves.

Rather than become a ranting lunatic–though some of his former players might argue that at times he was–Parcells figured out how far he could push each of his players–and then tried to push them even further.

The other side of Parcells' brilliance was that for as much as he dished it out, he also was man enough to take it, especially from the players he challenged.

Banks learned that during a particularly embarrassing incident that happened during a game against the Los Angeles Rams in his rookie season. That week, the Giants had played a sloppy, penalty-filled game that, with each yellow flag, was raising Parcells' blood pressure to new levels.

Parcells became so irritated with his team's lack of attention to detail that he vowed to cut the next player who committed a penalty.

That happened to be Banks, whose penalty came on a kickoff when he engaged in a shoving match with his opponent.

"I came off the field to the sideline, and he told me to sit my you-know-what down and that I was cut," Banks said.

"I came back, and I lashed out back at him, and he was like, 'What did you say?' I said what I said again, and he just turned around and went back to coaching the game. When I showed up for work that Monday, I didn't know whether I had a job or not."

Banks did indeed have a job after giving Parcells what he was looking for–no, not a verbal retort to the coach's in-game button-pushing, but a Hall of Fame quality performance week in and week out.

No Cutting in Line

How the SEC Became Goliath: The Making of College Football's Most Dominant Conference,

Ray Glier (2012) Jan. 5, 2009

To: mhamilton@tennessee.edu Mike, I do hope you budgeted extra money for NCAA violations defense expenses. ... Jan. 5, 2009 From: Hamilton, Michael Edward We haven't received penalties for a major violation since the 80s, so we're not planning on changing that now ... we have a proactive compliance program. Jan. 23, 2009 To: mhamilton@tennessee.edu The athletic department is out of control. Feb. 16, 2009 To: mhamilton@tennessee.edu Someone from the coaching staff over at the UT circus has been in discussions with the athletic director at [REDACTED] High School. The AD didn't quite understand what the coach was selling/telling him; he was too shocked at hearing a Tennessee football coach recommend that a high school kid drop out of school before graduating ... this gambit would somehow get the kid an extra year of eligibility. ... Feb. 27, 2009 To: mhamilton@tennessee.edu Subject line: "If you ain't cheating, you ain't trying." Mike ... Players are being asked to falsely affirm the number of hours they practice each week. Mike Hamilton, the University of Tennessee athletic director, would find these e-mails from his staff in his in-box routinely in the winter of 2009. Lane Kiffin, his football coach, was a tireless recruiter and was going to prove to be a masterful play-caller, but Hamilton's staff ... thought the 33-year-old coach was in too much of a hurry to get his own national championship trophy. Kiffin had the Vols hooked to his fast sled, which was to win now and challenge the Gators and Tigers and the rising Tide. Kiffin was trying to cut in line. ...

Kiffin, who had been hired to replace Phil Fulmer, quit January 12, 2010, after one season, a 7-6 campaign in 2009, which ended with a 37-14 thumping at the hands of Virginia Tech in the Chick-fil-A Bowl. The night Kiffin quit, T-shirts were burned on campus ... Students were angry at the coach who vowed to get Tennessee back on the same level as Florida and Urban Meyer but bolted for the head coaching job at Southern California. But inside Stokely Athletic Center, where the UT athletic offices were located, there was some rejoicing. Kiffin was gone. Good riddance, many thought to themselves. ...

Some perceived that Kiffin was just doing his part to uphold what was viewed as a culture of rule-bending in the Southeastern Conference. It is supposed to be the Wild West with the familiar phrase being uttered, "It is better to beg forgiveness than ask permission." But something was more ominous about Kiffin's style, something worse than bending a few rules. The old-school Tennessee fans, including staffers on campus, saw Kiffin sneer at UT traditions. ... That was Kiffin's big misstep around Knoxville. He got on the wrong side of Old Smokey. He also got on the wrong side of the other coaches in the SEC. In February 2009, Kiffin accused Florida coach Urban Meyer of cheating, then backed down and apologized. Kiffin's mirror must have been broken. He was the one cheating. He was accused of six secondary violations of NCAA rules, which included disclosing the name of an unsigned recruit on Twitter and setting up press conferences with a photographer present to impress recruits.

L-R: Mike Hamilton and Lane Kiffin Headline writers around the SEC had a good time with the Tennessee coach. He was called Boy Blunder and Lane Violation. That was too bad because Kiffin can coach and could recruit, but it was all obscured by missteps and spitting on some sacred Tennessee traditions. It wasn't just the loyalists of fired coach Phil Fulmer who had it in for Kiffin; others around the department thought the rookie college head coach had way too much swagger.

Kiffin had come from the Oakland Raiders, fired by Al Davis, who was assumed to be a reckless owner. After a few months on campus, Kiffin was giving the impression that he was reckless, that he had deserved to be pushed out at Oakland, that Davis was not such a kook after all.

Hamilton and his compliance officers made attempts to keep Kiffin under control and within the boundaries of the NCAA rulebook. One of the department's compliance officers went out to football practice on February 17, 2009, and coaches suddenly disappeared from a 7-on-7 "voluntary" workout. According to NCAA rules, the coaches were not allowed to be present with footballs before spring practice began. But according to sources, the coaches reappeared, so did the footballs.

One former player, who did not want to be identified, said spring practices did not begin in March, the legal starting date, but on crisp February mornings. ...

Did Kiffin understand the rules? He was a new head coach in college football, but not new to the game. He had nine seasons as a college assistant coach. The NCAA manual is thick, sure, but he and his assistants were not just out of high school. ...

What was not excusable to some Vol fans was Kiffin's disregard for some traditions.

The day after Kiffin resigned as Tennessee coach, Josh McNeil, an offensive lineman recruited by Fulmer, said in a phone interview that Kiffin was disgracing the Tennessee traditions. McNeil said Kiffin was even debating the merits of the most sacred tradition, the Maxims, which are on a tall board inside the locker room. ... The Maxims were Tennessee in-game prerequisites for winning that had survived since the hallowed days of the legendary coach General Robert Neyland. ...

"They'd replaced our highlight video from the past season with Reggie Bush, Matt Leinart, and Dwayne Jarrett from USC. I was like, 'Man, I know we were five and seven last year, but this is Tennessee. Right beside our national title trophy? Come on, man."

McNeil told [the AOL reporter] that he walked up the stairs to the Neyland-Thompson Sports Center, and twenty televisions were mounted in the building that had still photos on the screen. The colors were not orange, they were red, USC red. There was a shot of Reggie Bush, the former USC back, diving into the end zone. ...

People around the facility commented that Kiffin wanted to turn Tennessee into the "USC of the South," forgetting that Tennessee had won a national title in 1998 under Kiffin's predecessor, Phil Fulmer. McNeil finally had enough and confronted Kiffin, according to the AOL story. "Coach, I feel like you're intentionally not embracing UT's traditions."

Kiffin replied, "Well, whatever Tennessee's been doing isn't working anymore, so we're coming up with something new. Get used to it." ... "Coach Kiffin cared about Tennessee traditions less than the worst Vol hater in the state of Alabama," McNeil said. "That man's a snake." ...

Plenty of fans were tickled by (Kiffin's) brashness, especially when it came to Florida and the other rivals, but Kiffin walked a fine line with former players.

"Lane Kiffin was a terrible hire for the University of Tennessee, but that was not his fault," said David Moon, a former UT player ... "You can't fault a skunk for smelling bad. But you can fault the guy who brings a pack of skunks in the house." ...

Kiffin was never charged with a major violation at Tennessee. In a statement from Los Angeles on August 24, 2011, Kiffin said, "I'm very grateful to the NCAA, the Committee on Infractions ... for a very fair and thorough process. I'm also very grateful that we were able to accurately and fairly present the facts in our case and that no action was taken against us. ... I'm also very grateful that the Tennessee football program was cleared of any wrongdoing." ...

Hamilton resigned as Tennessee athletic director in June 2011 ... He told the Chattanooga Times Free Press he had to leave Knoxville because of threats to his family.

"It reached a point that I moved my family out of Knoxville for several days last spring [2011] and I was even assigned police protection," Hamilton told the paper. Hamilton told the newspaper that he and his wife have five young, adopted children, "so I had to stop and realize life is short and it was time to reassess my priorities." Playoff Lenny

Ron Higgins, Tiger Rag Extra: LSU's Super Bowl Six, March 2021

Leonard Fournette showed up for work, 13 days before the start of his fourth NFL season as a running back for the Jacksonville Jaguars. The former LSU all-American, the fourth overall pick in the 2017 NFL draft, was feeling healthy which was a good sign. Because when he had some pop in his well-used legs, he produced a pair of 1,000-yard rushing seasons as a rookie when he helped the Jaguars to the AFC championship game and in 2019 when he accounted for 30.6 percent of the Jags' offense.

Though there had been some turmoil in the months leading to the 2020 season - Jacksonville declined Fournette's fifth-year option in his contract last May and tried to unsuccessfully trade him and his $4.2 million salary - he was happy to get back to work in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic.

Until that Aug. 31 morning when he pulled up at the entrance of the fenced Jaguars' practice facility. "Someone was at the gate saying (head) Coach (Doug Marrone) wants to see me," Fournette recalled. The meeting didn't last long. Marrone told a stunned Fournette he was releasing him from the team. "There was no explanation," Fournette said. "It just happened; it was a terrible feeling."

A couple of days later in a press conference, Marrone explained why he cut Fournette. "At the end of the day, we feel the skill sets of the guys that we have (can replace Fournette), and really that's what led to the decision," Marrone said.

For the first time in his football life that started on the playgrounds of New Orleans' Seventh Ward and traversed through St. Augustine High and LSU, the guy who always had been running back No. 1 on every depth chart, who got the most carries, who shouldered the offensive load against defenses stacked to stop him, was told he was not good enough to stay on a roster.

Leonard Fournette with St. Augustine, LSU, Jacksonville, and Tampa Bay. Just about six months later to the day, he officially signed with a new team and around three weeks removed from his 26th birthday, Leonard Fournette walked off his homefield in Tampa on the night of Feb. 7 a Super Bowl champion after the most satisfying game of his career as the starting running back for the Tampa Bay Bucs.

The former first-round draft choice that Jacksonville dumped without taking any trade deal to get players in return had just run through the defense of defending Super Bowl champion Kansas City for 89 yards including a 27-yard third-quarter touchdown on 16 carries. He also caught four passes for 46 yards, not dropping any ball thrown his way or the Lombardi Trophy awarded to the Bucs for their dominating 31-9 Super Bowl 55 victory.

In Zoom media interviews afterwards, Fournette was asked to reflect on his journey from the Jacksonville cut list to being sized for a Super Bowl championship ring after his performance of redemption. "I don't have to say too much," Fournette said with a thin smile. "You all know, we all know, I'm just blessed, so I'm going to leave it there."

He didn't say it, but Fournette was probably hoping that Maronne, the coach that gave up on him, got an eyeful in his crowning moment of glory. Maronne certainly had time to watch the game since he was fired Jan. 4, a few days before Fournette started his four-game romp through playoffs in which he ran for 300 yards and three TDs on 64 carries and caught 18 passes (21 targets) for 148 yards and 1 TD.

"He was amazing and just did it all, blocked, ran, just had an incredible season," said Bucs' 43-year old seven-time Super Bowl champion QB Tom Brady, who Fournette calls "Old Head." "We got him pretty late and he just showed up big. It was amazing how he performed in the biggest moments. Just so proud of him."

Fournette's regular season stats, 397 yards rushing and six TDs on 97 carries and 36 receptions for 233 yards in 13 games with three starts, were a far cry from his 1,000-yard rushing seasons as a Jaguars' rookie in 2017 and in 2019 when he averaged a combined 19 carries per game.

His role for most of the 2020 regular season - as a backup to starter Ronald Jones - was completely foreign to him and difficult to swallow. Suddenly, Fournette was living in a world that former LSU backup running back Darrel Williams had tolerated for four years of college and three NFL seasons with the Chiefs.

"It was a tough year for me," Fournette said. "As a competitor you want to be out there, you want to compete. You want to play as hard as you can and help the team."

Todd McNair, Tampa Bay's running backs coach who played eight NFL seasons as a third-down back, a lead blocker and special teams player, sympathized with Fournette. But he also gave him tough love.

"The biggest thing with Leonard was him accepting his role and accepting he wasn't THE superstar, wasn't THE man," McNair said. "Some guys since high school have gone through their whole career where they've been coddled. Sometimes when you get released, you have to be shocked into reality like this can go on without you. If you're self-reflective, if you're true and honest with yourself, you can say, 'OK, maybe I need to change this; maybe I need to change that.'

"With any team that's successful, the approach is, 'What can I do for my team, not what can the team do for me?' It's a testament to the way Leonard embraced his role. You never know in this league. You can be THE man one minute, you could be traded the next."

Every time Fournette got discouraged during the season, he took solace in family time just as he did for a week after being cut. "I was chilling with my kids (after he was cut)," Fournette said, "and I realized they are my why in why I do this, they are why I play, this is what I'm doing it for, I'm doing it for them. I just tried not to lose focus on the bigger picture of what's going on and just kept going forward."

When Jones missed the final three regular season games after contracting COVID, Fournette stepped into the starting spot and never took his foot off the gas. Just as he did with the Jags' 2017 three-game playoff run when he ran for 272 yards and four TDs on 70 carries to earn the nickname "Playoff Lenny," he came alive while discovering a new truth. His vastly lighter regular season workload resulted in considerably fresher legs in the biggest games of the year to write a storybook ending to a season that started for him as a nightmare.

|