|

Basketball Short Story

Demise of the Post Game

"The Lost Art of the NBA,"

Chris Ballard, Sports Illustrated (February 2023)

For generations, giants ruled from the blocks. Today? Post play is an afterthought, lost to pace and space. But there remain a few who preach the forgotten craft - and seek its return.

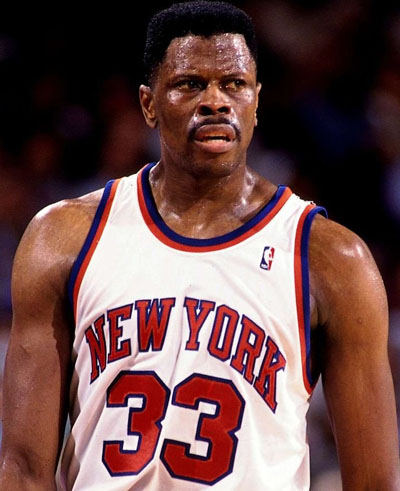

Exactly how and why the post game vanished is a matter of debate. Some go back to the addition of the three-point line, in 1979, originally installed as another anti-big-man measure. Others point to the long-term effect of rule modifications. Tired of low-scoring wrestling matches, the NBA in '94 began strictly enforcing existing hand-checking measures on the perimetert. Now, a wing like Michael Jordan could attack without an enforcer's grappling hooks in his hips. But a big with his back turned? "You could still maul him,' says Jeff Van Gundy, who coached a succession of top centers, from Patrick Ewing to Yao Ming to Dikembe Mutombo.

L-R: Patrick Ewing, Yao Ming, Dikembe Mutombo Eight years later, in 2002, the NBA went one step further and legalized zone defenses, effectively eliminating a post player's air space. Whereas coaches once had to choose whether to send a hard double team on the catch, now help D could float nearby or sandwich a big before he even got the ball. Even the most basic post entry pass became perilous.

Then, of course, there's the Dirk-ification of the game. That traces all the way back to FIBA's superwide trapezoidal lane, forcing American bigs away from the hoop. (As you can see, the history of basketball is largely a history of penalizing tall people for being tall.) This encouraged international bigs to learn the game by facing up, away from the basket, and thus Dirk Nowitzki begat Kirstaps Porzingis and Giannis Antetokounmpo and Nikola Jokic.

Sure, you may be thinking, but we all know what really killed the post-up, the stake through its old-school heart. BA teams finally did the math: 3 > 2. Hoops analytics may have begun on the fringe, but by the mid-2010s, the revolution was complete. Three-pointers and free throws were the new Holy Grail. Midrange shots and postmoves were anathema. By '15, Grantland's Zach Lowe was asking whether, in its zeal to make the game more exciting, "the league inadvertently killed the back-to-the-basket game."

No player's career better illustrates that sea change than that of Brook Lopez. First at Stanford and then with the Nets in the early 2010s, Lopez starred on the block, deploying an array of soft half hooks and bank shots. For the first eight years of his NBA career, Lopez scored 20 a game while rarely, if ever, attempting a three-pointer. "I absolutely loved posting up," Lopez says. Then, in the summer before the '16-17 season, Nets coach Kenny Anderson told him to start practicing his threes. That season, Lopez launched five threes a game, or two more than Larry Bird did in any year of his career. Lopez adapted and survived, but others struggled. (RIP, Greg Monroe's NBA career.) The Warriors asked bigs not to post up but to set screens, roll and become pocket passers preaching, "on time, on target." Centers who couldn't shoot became a liability - as did those who couldn't guard on the perimeter on a switch, leaving them marooned against the likes of Trae Young and Steph Curry, launching 26-footers off the dribble.

Spacing became the new currency of the league. Everyone needed to be able to shoot. "It's like mining for gold or going after oil," says Bucks assistant coach Mike Dunlap. "Everyone's fighting for more space to operate, because the players are so quick and long. ... The game used to be east-west. Now it's north-south."

L-R: Dirk Nowitzki, Nikola Jokic, Brook Lopez This is not to say skilled post-up players don't still exist in the NBA; it's just that teams don't give them many opportunities. This season, only one player, Jokic, has posted up more than five times per game. To find other post-up specialists you often need to look down to the end of a team's bench or more often, to its guards.

For the most part, though, the post-up is, as Van Gundy says, "dying a pretty quick death." Whereas guards like Kobe Bryant once hoped to acquire the skills of big men, now big men, such as Joel Embiid, seek out training gurus like Drew Hanlen, a former collegiate point guard, to help them play like Kobe.

This feeds into a continuous cycle, as Newell Jr. sees it: Players today don't recognize how to play and pass to the post. Why not? Because they're not taught. And why aren't they taught? Because no one wants to - or knows how to - teach it anymore. "Most coaches," he says, "were perimeter players when they played. So they can't see the game through the center's eyes."

Indeed, ask around and there is no Pete Newell Sr. of today. This is not surprising. Supply and demand, etc. If the Warriors post up only twice a game the pace they're at this season - why would they focus on teaching it? |