|

Baseball Short Story

Friendly Foes

Memories and Dreams: The Official Magazine of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

(Fall 2022), Scott Pitniak From his vantage point as the Kansas City Monarchs' first baseman that dank day at Pittsburgh's Forbes Field, Buck O'Neil had a bird's eye view of one of the most anticipated duels in sports history. Satchel Paige, the fast-talking, fast-throwing pitcher, was facing Josh Gibson – the muscular slugger who Monte Irvin said "was as strong as two men" – in Game 2 of the 1942 Negro Leagues World Series.

"It was," O'Neil would say years later, "the most desired confrontation in the history of Black baseball, one that boiled down a hundred years of history into one at-bat.

One man was armed with arguably the best arm of all time – and a clever mind to match. The other boasted a bat that could pulverize pitches like tee shots.

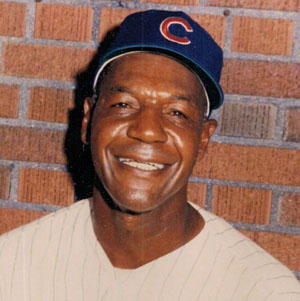

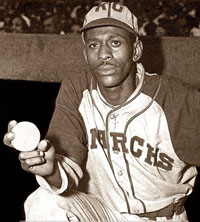

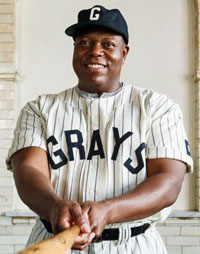

L-R: Buck O'Neil, Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson "What a showdown that must have been," said Negro Leagues Baseball Museum president Bob Kendrick, O'Neil's longtime friend. "Two immovable objects going at one another for competitive bragging rights. Oh, what I wouldn't give to go back in time and be in the stands for that one."

During that Sept. 10, 1942, matchup, Paige would get the better of his former batterymate and friend. He struck out the Homestead Grays' strongman, though accounts of how it unfolded vary, depending on the storyteller.

There were several other diamond duels between these two titans, including some when Gibson bested his friendly foe and rocketed Paige pitches off and over walls.

"Buck mentioned a time, the very next season, when Josh hit a ball so hard it tore the glove off one of his fielders," Kendrick recalled. "While the guy retrieved his mitt, a shocked Satchel looked over at Buck and told him: 'I'm just happy he didn't hit that one through the box, 'cuz if he had, I'd been meeting my maker."

It's unfortunate, Kendrick said, that there weren't "a ton of matchups between the two because whenever they went at it, there was sure to be fireworks one way or another, with fans on the edge of their seats."

Paige and Gibson were intense competitors who spent years taunting and mocking each other, frequently debating who was better. But those who knew them said they didn't allow their rivalry to detract from their friendship – a friendship, which, by the way, has spread through generations of offspring.

"It's like when you're playing golf or cards or some other game against your friends," said Sean Gibson, the slugger's great grandson and executive director of the Pittsburgh-based Josh Gibson Foundation. "You want to beat your buddies. You want to win. But when all's said and done, you're back to being friends."

In many respects, they were as different as a fastball and a slow curve; a tape-measure homer and a dribbler. Known for his prodigious wallops, Gibson preferred to let his booming bat do his talking. "For Black baseball, Josh was our John Henry," Kendrick said. "A big, strong, silent-type folk hero."

Lore has it that Henry hammered holes into rock for the dynamic sticks used to blast out railroad tunnels. Josh's legend was built on hammering baseballs.

"When he came to the plate, there was always a great sense of anticipation," Kendrick said. "Where into the universe was he going to hit one of these balls? With him, you used landmarks to point out how far he hit 'em. 'See that warehouse over there? Or those train tracks beyonod that fence? Or those trees way off in the distance? Well, Josh hit balls there, there and there.'"

Sportswriters often referred to Gibson as the "Black Babe Ruth" or the "Brown Bambino." But O'Neil, who was inducted posthumously into the Baseball Hall of Fame this summer, thought the comparisons could have been switched.

"Those of us who saw Josh play think that maybe Ruth could have been called the 'White Josh Gibson,'" O'Neil said.

With Paige, there also was a sense of anticipation because he was a pitcher who could blow batters away with fastballs so fast they were heard but not seen, or trick them with an assortment of pitches he assigned clever nicknames. Paige was the consummate entertainer, always interacting with – and occasionally agitating – players and fans. Garrulous and outgoing, he could pitch and talk a great game.

"He had what Hollywood calls the 'it' factor; a presence," Kendrick said. "He loved that he had 'it.' There's no doubting he enjoyed performing and being the center of attention and telling you how spectacular he was. But they say it's not boasting if you can back it up, and Satchel did. If you take into account his vast repertoire of pitches, his longevity and his charisma, he is, in my estimation, the greatest pitcher of all time."

Despite differences in temprament and skills, Paige and Gibson would become forever "joined," as Kendrick put it, "in history at the hip." The slugging catcher and slinging pitcher became teammates on barnstorming ballclubs in the United States and Caribbean, and with the Pittsburgh Crawfords, a 1930s Negro Leagues juggernaut.

Advertisements billed them as "The Greatest Battery in Baseball" and carried the guarantee that Gibson would smack two homers and Paige would strike out the first nine men. "We usually," explained Paige, "lived up to the hype."

They loved razzing one another about who was better, and while playing winter ball together in Puerto Rico in the early 1930s, Gibson allegedly told his friend: "Someday, my whole family is going to be in the stands and all your friends, too. ... You'll be pitching, and I'll come up with the bases filled. Know what I'm going to do? I'm going to drive you and the ball clear out to left field."

Paige scoffed and reportedly retorted: "You can't hit what you can't see."

While Gibson dug into the batter's box before their famous Negro Leagues World Series showdown, Paige was sure to remind his friend of the prediction made years earlier. They had squared off several times during the 1942 season, with Paige dominating the Grays' cleanup hitter most of the time. After speedy Homestead CF Jerry Benjamin reached third base with two outs in the seventh inning of Game 2 of the Series, Paige called O'Neil over and told him he was going to walk the next two batters so he could face Gibson. O'Neil immediately motioned for Kansas City manager Frank Duncan to come to the mound.

"Listen to what this fool wants to do," O'Neil told his skipper.

Duncan listened and just shrugged, because as O'Neil later explained to author Joe Posnanski: "You didn't exactly manage Satchel Paige. You just held on for dear life."

And that's what they would do as Paige sought to make his friend eat his words.

Accounts of what happened next differ. A report in the Washington Afro-American newspaper described Gibson fouling off the first two pitches before swinging and missing at strike three. Paige, in his memoir, wrote that he warned Gibson he was going to throw him two fastballs, and the slugger swung and missed both times.

Then, before tossing the third pitch, Paige claimed he told him: "I got you 0-and-2, and in this league I'm supposed to knock you down. But I'm not gonna throw smoke at yo' yolk. I'm gonna throw a pea at your knee."

Paige recounted tossing a knee-buckling curve that froze Gibson as it broke over the plate for strike three. O'Neil, who provided the most entertaining version, said the befuddled Gibson never removed his bat from his shoulder during the at-bat, taking three called strikes.

What's irrefutable is Mighty Josh struck out with the bases loaded. And after the whiff, Paige reportedly told everyone within earshot: "Ain't no man alive who can hit Satchel's fastball."

In the ensuing seasons, Gibson would exact some revenge. He reportedly smashed one of Paige's pitches off the scoreboard clock at Chicago's Comiskey Park, and Negro League contemporary Ted "Double Duty" Radcliffe recalled a game at Wrigley Field in which Gibson clubbed three home runs off Paige.

Gibson and Paige had hoped to become the first players to integrate the National and American Leagues, and there had been newspaper reports they were the leading candidates. Insted, Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey assigned that daunting challenge to Jackie Robinson. On Jan. 20, 1947 - less than three months before –'s debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers – Gibson died of a brain tumor at age 35. Paige got his chance to pitch in the American League the following season when Cleveland owner Bill Veeck signed him.

In 1971, Paige became the first Negro Leagues star inducted into the Hall of Fame. A year later, Gibson joined him in Cooperstown. News of the slugger's enshrinement revived stories of the at-bat that resulted in what Gibson biographer Mark Ribowsky called the "mother of all strikeouts and of all Black ball moments."

|