LSU Short Story

Bud Johnson, theundefeated.com (2017)

It was Christmas Day in 1972 when Louisiana State University men's basketball coach Press Maravich made a racist remark to describe the University of Houston's black players. As the father of Hall of Famer "Pistol Pete" Maravich uttered the hurtful words, Collis Temple Jr., LSU's first black varsity basketball player, listened to his coach. Maravich later added salt to the wound by describing Temple Jr. as a "credit to his race." "They were all brothers at Houston and they beat us pretty good," Temple Jr., 64, told The Undefeated. "We had practice two days before the game and Press referred to those guys as 'jumping jungle bunnies.' He was talking about how they would block shots, they could play and they could jump. He used the term 'jumping jungle bunnies' and then he looked at me, I guess, a jumping jungle bunny, too. |

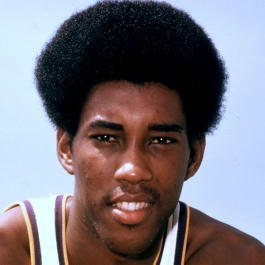

Collis Temple Jr. |

"After practice, he talked to me with the assistant coach and said, 'I didn't really mean nothing about that. That wasn't directed at you and I need you to know that you are a credit to your race.' In other words, 'Your race ain't s—, but you're all right.'"

The Temple family has a 60-year history with the university.

Collis Temple Sr. was not allowed to go to graduate school at LSU because he was black. Although two of his children graduated from the school, they experienced their fair share of racism. As the school's first black basketball player, Temple Jr. endured racist words from his coach, teammates, a young white nationalist named David Duke and opposing fans. Years later, two of Temple Jr.'s sons played basketball at LSU, including Sacramento Kings guard Garrett Temple — a member of LSU's all-black starting lineup in the 2006 Final Four.

Hours before the Kings honored his father for Black History Month during a game against the Phoenix Suns on Feb. 3, Garrett Temple talked to The Undefeated about how proud he was.

"I sometimes forget how powerful his story is because I lived with it," Garrett Temple, 30, said. "I grew up hearing stories at a young age. I'd be 6 or 7 years old and we'd be watching, 'Roots,' and it would lead to a story about him at LSU and what he had to go through. The things he was able to do and withstand at LSU are unimaginable and it makes me think about how forward-thinking my grandfather was to send him there after what LSU did to him."

In the early 1950s, Temple Sr. was determined to go to graduate school at LSU and had the grades to get in. LSU, however, did not accept him into the school because he was black. According to Temple Jr., the NAACP represented his father and filed a class-action lawsuit against the institution. After years of battle in court, the state of Louisiana agreed to a settlement in the mid-1950s to pay full tuition for Temple Sr. to attend any out-of-state school. Temple Sr. accepted the offer and attended Michigan State University.

"The deal was, 'Listen, Temple, we're going to pay for you to go to school, but you can't come to LSU,' " Temple Jr. said. "But you can go to any other school in the nation, so he went to Michigan State on the state of Louisiana's dime. Do you want to continue this lawsuit for 10 to 15 years or get a degree on a master's level?' I remember going to Lansing, Michigan, when I was like, 6 years old, to see my daddy graduate."

Temple Jr. became a three-sport athlete at the all-black Dillon High School in the late 1960s. Entering his senior year, he and his black classmates were sent to integrate previously all-white Kentwood High School in Kentwood, Louisiana, in 1969. He played on the 1969 Louisiana Class A state-integrated championship football team.

"You remember that 'Remember the Titans' s—? It was the exact same thing. I was thinking, 'They must have done this movie off us,' " Temple Jr. said.

He also remembers the backlash from white adults who didn't want black students to integrate Kentwood High School. The local police and U.S. National Guard helped the black students to enter the school safely.

"They had people with guns, pitchforks and some other bulls—," he said. "Some old farmers didn't want us in the school. They didn't bother us football guys when we practiced, but when school started it was a different game because those white folks didn't want to let us up in there.

"I never talked to white people when I was growing up. That is how segregated we were. I didn't talk to white people, because my parents wouldn't allow me to. They didn't want them calling me N-word or degrading me or having a real problem that my dad would have to solve. You had two separate worlds and you stayed in your lane."

Temple Jr. was recruited by a number of major colleges during the 1969-70 season. The 6-foot-8 big man was most interested in playing for Houston or Colorado. However, he said, a white lawyer in Kentwood approached his father about his son going to LSU instead due to the university's lack of black athletes.

Then-Louisiana Gov. John McKeithen arranged a meeting to try to persuade his parents to send him to LSU. McKeithen had no clue that the state had not allowed Temple's father to attend LSU previously.

"After that conversation went down, it was over," Temple Jr. said. "My dad told the governor that it was real ironic that he wanted his son to go to the school after he was denied, denied, denied. The governor said that it was a different time and different world and they were making up for lost time."

McKeithen promised the Temples that their son would be safe at LSU, whose first black athlete, track athlete Lloyd Wills Jr., arrived in 1969.

Temple Jr. said he was coached by a "very racist" Maravich for two years before the coach was replaced by Dale Brown in 1972. Brown said he didn't know Maravich, but said that he remembered Temple Jr. telling him about the racism issues he had with his former coach.

"[Maravich] tried to be accommodating and nice to me, but he was extremely racist," Temple Jr. said.

He also had issues with teammates. "I played with teammates that called me n—– and got into physical altercations with me," Temple Jr. said. "I broke up practice. They couldn't finish practice and they didn't practice the next day because I was so irritated and frustrated about what was happening. I was playing with [point guard Mike Darnell], who wouldn't pass me the ball and would call me a n—–. He's a point guard and I had to deal with this fool for three years.

"My coach couldn't force him to pass me the ball. He would tell him to pass me the ball and this fool would hit me on my ankle with the ball, he would hit my knee with it. I would make a turn to post up and he would hit me in the back of the head with the ball. This is my teammate. He could do better. He was a better player than that. We would get into fights and shouting matches. I am playing on a team trying to win. I am playing against Kentucky and my teammates."

The hostility wasn't limited to his coach and teammates, Temple Jr. said.

Martin J. Broussard, the LSU athletic trainer whose name is on the university's multimillion-dollar athletic training facility, also made racially insensitive remarks. Temple Jr. said Broussard, who died in 2003, once told him to get his "a– out of the training room" because he was a n—–, after Temple Jr. came to him seeking to be treated for a sprained ankle.

Temple Jr. said he was also taunted while playing.

"I forgot my name was Collis," he said. "I didn't know if my name was, 'Leroy,' 'coon,' or 'boy' or 'n—–.' The worst place for me was Mississippi State. They called you 'n—–,' 'coon,' 'spook,' 'stop the buck,' and 'Sambo.' They called you a bunch of names. Ole Miss had a black player my age, the same class, named Coolidge Ball, and they were talking about Coolidge and he was on the team."

With Brown as coach, Temple Jr. had quite a different experience. During his interview with LSU, Brown made it clear that he would recruit "human beings first and basketball players second." But some locals didn't feel the same way. After landing the job, he got a letter from a fan that called him a "n—– lover."

Brown recalled seeing one of his players slide a note under Temple Jr.'s door when he was doing a bedroom check not long after landing the job. He was able to get the note without Temple seeing it and was disgusted by what he read.

"I finished bed check and came home and read the note and it made me throw up," Brown said. "I don't remember the exact words, but it was like, 'You jungle bunny, you ain't wanted around here.' All this blah, blah, blah, blah, 'Go back to where you came from.'

"So I called the kid into the office. I told him, 'You know what I feel like doing, knocking your a– through that plate-glass window. But I'm not going to do it. I'm going to talk to you like a man.' He was scared of me. That's why he didn't do anything. But he was 100 percent racist."

Despite the hostility, Temple Jr. averaged 15.0 points and 10.5 rebounds per game as a senior and earned All-SEC honors. The Tigers upset No. 6 Vanderbilt, 84-81, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on Jan. 12, 1974. According to Temple Jr., the then-Vanderbilt guard Jan van Breda Kolff, a former NBA and ABA player who later coached at Vanderbilt, called him the N-word, which resulted in a fight breaking out.

"I kicked him in the side for calling me a n—–," Temple Jr. said. "We were playing in a hot game and I was guarding him before fouling out. Jan van Breda Kolff came to Baton Rouge three years ago for us to have a makeup. We're cool now. I was done with it after I kicked him."

The Tigers played the Commodores in Nashville, Tennessee, later that season and police informed Brown beforehand that they had received a threatening phone call saying he and Temple Jr. could be shot and the team bus could be bombed if Temple Jr. was on it. Temple Jr. still opted to play. Police officers sat outside of Brown's and Temple Jr.'s doors at their Nashville hotel rooms the night before the game and Tennessee Highway Patrol escorted Temple Jr. to the game.

"I had to make this grand entrance and had to deal with some real-deal stuff," he said.

Temple Jr. graduated with a bachelor's degree in education in 1974. He was drafted by the Phoenix Suns in the sixth round of the 1974 NBA draft and in the third round by the ABA's San Antonio Spurs. He spent his lone professional season with the Spurs and roomed with Hall of Famer George Gervin on road trips. He scored 42 points in 24 games during the 1974-75 season.

Despite his struggles, Temple Jr. has remained loyal to LSU. In 1979, he returned for his master's degree in education. He has served on the board of directors of the LSU Alumni Association, Tiger Athletic Foundation, National L Club and LSU Junior Division Advisory Board. He was one of 15 LSU basketball players chosen by fans for the All-Century Team. In 2010, he was named to the LSU Alumni Association's Hall of Distinction, which recognizes alumni who have distinguished themselves through their careers, personal and civic accomplishments, volunteer activities and loyalty to the school. But despite these accolades and involvement, Temple Jr. still hasn't been selected for LSU's Athletic Hall of Fame, which recognizes former athletes who have made a lasting impact at the school.

The Temple family has a 60-year history with the university.

Collis Temple Sr. was not allowed to go to graduate school at LSU because he was black. Although two of his children graduated from the school, they experienced their fair share of racism. As the school's first black basketball player, Temple Jr. endured racist words from his coach, teammates, a young white nationalist named David Duke and opposing fans. Years later, two of Temple Jr.'s sons played basketball at LSU, including Sacramento Kings guard Garrett Temple — a member of LSU's all-black starting lineup in the 2006 Final Four.

Hours before the Kings honored his father for Black History Month during a game against the Phoenix Suns on Feb. 3, Garrett Temple talked to The Undefeated about how proud he was.

"I sometimes forget how powerful his story is because I lived with it," Garrett Temple, 30, said. "I grew up hearing stories at a young age. I'd be 6 or 7 years old and we'd be watching, 'Roots,' and it would lead to a story about him at LSU and what he had to go through. The things he was able to do and withstand at LSU are unimaginable and it makes me think about how forward-thinking my grandfather was to send him there after what LSU did to him."

In the early 1950s, Temple Sr. was determined to go to graduate school at LSU and had the grades to get in. LSU, however, did not accept him into the school because he was black. According to Temple Jr., the NAACP represented his father and filed a class-action lawsuit against the institution. After years of battle in court, the state of Louisiana agreed to a settlement in the mid-1950s to pay full tuition for Temple Sr. to attend any out-of-state school. Temple Sr. accepted the offer and attended Michigan State University.

"The deal was, 'Listen, Temple, we're going to pay for you to go to school, but you can't come to LSU,' " Temple Jr. said. "But you can go to any other school in the nation, so he went to Michigan State on the state of Louisiana's dime. Do you want to continue this lawsuit for 10 to 15 years or get a degree on a master's level?' I remember going to Lansing, Michigan, when I was like, 6 years old, to see my daddy graduate."

Temple Jr. became a three-sport athlete at the all-black Dillon High School in the late 1960s. Entering his senior year, he and his black classmates were sent to integrate previously all-white Kentwood High School in Kentwood, Louisiana, in 1969. He played on the 1969 Louisiana Class A state-integrated championship football team.

"You remember that 'Remember the Titans' s—? It was the exact same thing. I was thinking, 'They must have done this movie off us,' " Temple Jr. said.

He also remembers the backlash from white adults who didn't want black students to integrate Kentwood High School. The local police and U.S. National Guard helped the black students to enter the school safely.

"They had people with guns, pitchforks and some other bulls—," he said. "Some old farmers didn't want us in the school. They didn't bother us football guys when we practiced, but when school started it was a different game because those white folks didn't want to let us up in there.

"I never talked to white people when I was growing up. That is how segregated we were. I didn't talk to white people, because my parents wouldn't allow me to. They didn't want them calling me N-word or degrading me or having a real problem that my dad would have to solve. You had two separate worlds and you stayed in your lane."

Temple Jr. was recruited by a number of major colleges during the 1969-70 season. The 6-foot-8 big man was most interested in playing for Houston or Colorado. However, he said, a white lawyer in Kentwood approached his father about his son going to LSU instead due to the university's lack of black athletes.

Then-Louisiana Gov. John McKeithen arranged a meeting to try to persuade his parents to send him to LSU. McKeithen had no clue that the state had not allowed Temple's father to attend LSU previously.

"After that conversation went down, it was over," Temple Jr. said. "My dad told the governor that it was real ironic that he wanted his son to go to the school after he was denied, denied, denied. The governor said that it was a different time and different world and they were making up for lost time."

McKeithen promised the Temples that their son would be safe at LSU, whose first black athlete, track athlete Lloyd Wills Jr., arrived in 1969.

Temple Jr. said he was coached by a "very racist" Maravich for two years before the coach was replaced by Dale Brown in 1972. Brown said he didn't know Maravich, but said that he remembered Temple Jr. telling him about the racism issues he had with his former coach.

"[Maravich] tried to be accommodating and nice to me, but he was extremely racist," Temple Jr. said.

He also had issues with teammates. "I played with teammates that called me n—– and got into physical altercations with me," Temple Jr. said. "I broke up practice. They couldn't finish practice and they didn't practice the next day because I was so irritated and frustrated about what was happening. I was playing with [point guard Mike Darnell], who wouldn't pass me the ball and would call me a n—–. He's a point guard and I had to deal with this fool for three years.

"My coach couldn't force him to pass me the ball. He would tell him to pass me the ball and this fool would hit me on my ankle with the ball, he would hit my knee with it. I would make a turn to post up and he would hit me in the back of the head with the ball. This is my teammate. He could do better. He was a better player than that. We would get into fights and shouting matches. I am playing on a team trying to win. I am playing against Kentucky and my teammates."

The hostility wasn't limited to his coach and teammates, Temple Jr. said.

Martin J. Broussard, the LSU athletic trainer whose name is on the university's multimillion-dollar athletic training facility, also made racially insensitive remarks. Temple Jr. said Broussard, who died in 2003, once told him to get his "a– out of the training room" because he was a n—–, after Temple Jr. came to him seeking to be treated for a sprained ankle.

Temple Jr. said he was also taunted while playing.

"I forgot my name was Collis," he said. "I didn't know if my name was, 'Leroy,' 'coon,' or 'boy' or 'n—–.' The worst place for me was Mississippi State. They called you 'n—–,' 'coon,' 'spook,' 'stop the buck,' and 'Sambo.' They called you a bunch of names. Ole Miss had a black player my age, the same class, named Coolidge Ball, and they were talking about Coolidge and he was on the team."

With Brown as coach, Temple Jr. had quite a different experience. During his interview with LSU, Brown made it clear that he would recruit "human beings first and basketball players second." But some locals didn't feel the same way. After landing the job, he got a letter from a fan that called him a "n—– lover."

Brown recalled seeing one of his players slide a note under Temple Jr.'s door when he was doing a bedroom check not long after landing the job. He was able to get the note without Temple seeing it and was disgusted by what he read.

"I finished bed check and came home and read the note and it made me throw up," Brown said. "I don't remember the exact words, but it was like, 'You jungle bunny, you ain't wanted around here.' All this blah, blah, blah, blah, 'Go back to where you came from.'

"So I called the kid into the office. I told him, 'You know what I feel like doing, knocking your a– through that plate-glass window. But I'm not going to do it. I'm going to talk to you like a man.' He was scared of me. That's why he didn't do anything. But he was 100 percent racist."

Despite the hostility, Temple Jr. averaged 15.0 points and 10.5 rebounds per game as a senior and earned All-SEC honors. The Tigers upset No. 6 Vanderbilt, 84-81, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on Jan. 12, 1974. According to Temple Jr., the then-Vanderbilt guard Jan van Breda Kolff, a former NBA and ABA player who later coached at Vanderbilt, called him the N-word, which resulted in a fight breaking out.

"I kicked him in the side for calling me a n—–," Temple Jr. said. "We were playing in a hot game and I was guarding him before fouling out. Jan van Breda Kolff came to Baton Rouge three years ago for us to have a makeup. We're cool now. I was done with it after I kicked him."

The Tigers played the Commodores in Nashville, Tennessee, later that season and police informed Brown beforehand that they had received a threatening phone call saying he and Temple Jr. could be shot and the team bus could be bombed if Temple Jr. was on it. Temple Jr. still opted to play. Police officers sat outside of Brown's and Temple Jr.'s doors at their Nashville hotel rooms the night before the game and Tennessee Highway Patrol escorted Temple Jr. to the game.

"I had to make this grand entrance and had to deal with some real-deal stuff," he said.

Temple Jr. graduated with a bachelor's degree in education in 1974. He was drafted by the Phoenix Suns in the sixth round of the 1974 NBA draft and in the third round by the ABA's San Antonio Spurs. He spent his lone professional season with the Spurs and roomed with Hall of Famer George Gervin on road trips. He scored 42 points in 24 games during the 1974-75 season.

Despite his struggles, Temple Jr. has remained loyal to LSU. In 1979, he returned for his master's degree in education. He has served on the board of directors of the LSU Alumni Association, Tiger Athletic Foundation, National L Club and LSU Junior Division Advisory Board. He was one of 15 LSU basketball players chosen by fans for the All-Century Team. In 2010, he was named to the LSU Alumni Association's Hall of Distinction, which recognizes alumni who have distinguished themselves through their careers, personal and civic accomplishments, volunteer activities and loyalty to the school. But despite these accolades and involvement, Temple Jr. still hasn't been selected for LSU's Athletic Hall of Fame, which recognizes former athletes who have made a lasting impact at the school.