Clash of Titans

Games featuring a future Hall of Fame coach on each sideline.

1927 Rose Bowl: Alabama vs Stanford

Wallace Wade vs Pop Warner

The 1925 Alabama football team stunned the college football world by upsetting Washington in the 1926 Rose Bowl. After another undefeated season which gave them a 20-game winning streak, the Crimson Tide got a chance to show they could do it again the following season, but they would face a more formidable foe – the Stanford Indians coached by the legendary Glenn "Pop" Warner.

Stanford enjoyed the greatest season in their 23-year football history. Using Warner's "baffling now-you-see-it, now-you-don't" double wingback offense, his third Stanford squad won all 10 games during the season while averaging 26 points per game. The only close contests were 13-0 over Caltech, 7-3 over the Olympic Club, and 13-12 at Southern California. Stanford outscored its opponents by 261 to 66 in winning the Pacific Coast Conference championship and the Rose Bowl berth that went with it.

In December, Stanford was selected as the national champion under the Dickinson System, a mathematical point formula devised by a University of Illinois economics professor.

Three Indians earned first team All-America honors: E Ted Shipkey, HB "Tricky" Dick Hyland, and G Fred Swan. Three others joined them on the First-team All-Pacific Coast squad chosen by sportswriters: HB/FB George Bogue, E Edgar Walker, and T Roland Sellman.

Despite only 10 lettermen returning from the 1925 squad that won the Rose Bowl, Wallace Wade's fourth Crimson Tide contingent surprised even their coach by winning all nine of their games to cop their third straight Southern Conference crown. By far the closest was the 2-0 squeaker over Sewanee in Game 5. The Crimson Tide held six of their opponents scoreless.

Hoyt "Wu" Winslett, an All-American end in 1926, recalled, "I suspect our 1925 team was a little better than the 1926 team, but we had some grit about us in 1926."

The '26 team benefitted from the experience of the returnees from the previous year's Rose Bowl trip. "We knew what the bowl business was all about when we made the return trip to Pasadena," said Payne. "We were full of confidence, not overconfident, just knowing what we had to do."

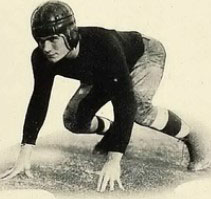

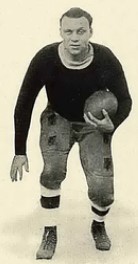

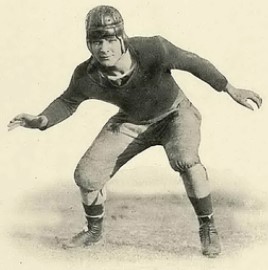

L-R: Glenn "Pop" Warner, Ted Shipkey, George Bogue, Roland Sellman

(Stanford University Quad Yearbook Class of 1927)

Several train carloads of Alabama fans accompanied the team on the cross-country trip.

Coach Warner invented the single wing offense, which was the system Wade used throughout his career. So the game would have "Master vs Apprentice" overtones.

Cocky Stanford Favored

Stanford was favored because some "experts" thought Southern football was inferior to West Coast football. However, the same thing was stated the previous year when Alabama defeated Washington.

Former Stanford star Ernie Nevers said his alma mater would beat Alabama by at least two touchdowns. One writer said Stanford "has no parallel in coast history." Those and similar remarks enraged the Alabama players.

"We regarded the contest with Stanford as just another game," said Alabama C Leslie Payne, "but every Alabama player had in his own mind that we were representing a lot of people in the South. There was more than a handful of people counting on us to do well."

Morgan Blake spoke for all sports reporters in the Southeast when he wrote in the Atlanta Journal: "They (Stanford) are trying to scare us to death before the game." He said he had never before "run across such an atmosphere of brag and boast."

Blake added, "Quite a contrast to this attitude is that of Coach Wade and his men, nothing cocky about Alabama. Plenty of confidence but no boasting. Coach Wade, to tell the truth, is delighted that his team has been such an underdog. The Alabama chief is doing everything in his power to lead the enemy to overconfidence. He is writing articles for local papers indicating ... that Alabama is only working on the defense and will only attempt to hold down the score. As a matter of fact, Alabama has done nothing but scrimmage on the offense since the trip started."

Alabama had the heavier line by many pounds per man. By playing a tight center with the tackles moved wide, Coach Wade and his staff believed they could stop Stanford's celebrated double- and triple-reverse plays inside and outside of tackle. Also, Alabama's secondary defense was considered the "fastest and smartest" Stanford faced during the season.

Warner must have winced when he read the comments of his cocky players. He said, "The game is a tossup. If I were a betting man, I'd place 10 smackers on Stanford and another 10 on Alabama." He had personally scouted Alabama in its last game with Georgia. Impressed with Bama's speed, Pop ordered silk pants for his team, which reportedly weighed only a pound-and-a-half.

The Rose Bowl was generally accepted by the nation's sportswriters as determining the national championship for the 1926 season.

The game was the first nationwide broadcast of the brand new National Broadcasting Company (NBC), a subsidiary of the Radio Corporation of America (RCA).

With pairs of tickets being scalped at $50 (an unheard-of price at that time) and the Rose Bowl having added 4,000 seats from the year before, a record crowd of 57,417 saw a defensive struggle.

When the Alabama players saw Stanford take the field in their silk pants, the Southerners made wisecracks like "shall we dance?" and "take those bloomers off and let's see what's underneath."

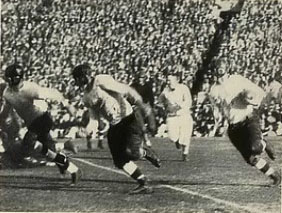

Ted Shipkey on an end around for Stanford (white jerseys)

(Stanford University Quad Yearbook Class of 1927

Stanford Starts with Trick Play

Warner wrote in his autobiography that the 1927 Rose Bowl "turned out to be a great chess match." He also said his 1926 team "was blessed with great speed, power, passing ability and the daring to pull off the big play. Knowing of these attributes, I had earlier planned for a bit of hocus-pocus to be used in the game with Alabama."

"All during the season, the Cardinal attack had been keyed around our great end, Ted Shipkey, and Dick Hyland, the speedy Stanford wingback. I knew that Wallace Wade had probably drilled his Alabama defense to keep a close eye on these two players. But the Tide defense would probably pay little attention to Ed Walker, our right end who hadn't been thrown a pass during the entire season.

"For our opening offensive play in the game, I had instructed both Hyland and Walker to trade positions. Alabama's safety—as I had predicted he would—then moved over to cover Walker, while thinking that he was covering Hyland. In the meantime, the real Hyland broke fast from the line of scrimmage and soon was all alone on the Tide 15-yard line. While downfield and looking over his shoulder, Hyland saw that the pass was going to be a bit short, so he abruptly turned and raced toward the ball, catching it on the Tide 27-yard line for a 45-yard gain.

"Hoffman then hit Hyland on another pass to the Tide 8. The Cardinal's advance was eventually stopped when a field goal attempt went wide."

L: Fred Swan chases Bama passer. R: Stanford's George Bogue follows his blockers.

(Stanford University Quad Yearbook Class of 1927)

Stanford quickly forced a punt, which Cardinal fumbled. Fortunately for the Cardinal, Shipkey recovered on the Bama 40. The All-American end then took the ball on one of Warner's famous reverses for a 25y gain. But Hoffman fumbled, and Alabama QB Hoyt "Wu" Winslett recovered.

The turnover circus continued when Bogue intercepted QB Emile "Lovely" Barnes' pass. This time, Stanford was not to be denied. Hyland and Bogue ran off tackle, and Hoffman went through the center on "spin plays" to put the ball on the 19.

Tricky Play Scores for Stanford

At that point, Stanford pulled off one of the cleverest plays of the game. At a given signal, Bogue started to run back toward his own goal. When he was directly behind the fullback's position, the ball was snapped. At the instant the ball left the center's hands, Walker swung back behind his own line. As soon as he passed his left tackle, he crossed the scrimmage line uncovered and turned in time to catch the short pass from Bogue. Walker then scampered the remaining 15y over the goal. Bogue kicked the PAT to make it 7-0 Stanford.

Stanford spent the rest of the game marching up and down the field to the tune of 305y to Bama's 98. But they could not add to their seven points.

Hyland was a problem child for Warner because of his penchant for leaving his interference, unorthodox handling of the ball, and ignoring orders. What happened in the next few minutes showed why the coach must have winced every time Hyland touched the pigskin.

Warner recalled, "In the second quarter I almost swallowed my cigarette while watching one of Hyland's crowd-pleasing antics."

Alabama penetrated Stanford territory in the second quarter. Short plunges put the ball on the 40 where the Tide bogged down. So Barnes punted to Hyland, who caught the ball on his 5, started to his left, saw he was hemmed in, reversed his field with Alabamans in close pursuit, and ran deep into his end zone. One of the Tide pursuers ran into the goal post and was knocked unconscious. Meanwhile, Hyland ran back into the field of play before being run out of the bounds at the 20 by the last Crimson defender between him and the Bama goal.

Winslett recovered another fumble for Alabama at the Stanford 23. But Lawrence "Spud" Lewis stifled the threat with an interception. Hoffman punted out of danger, and the second quarter soon ended.

Halftime score: Stanford 7 Alabama 0

L-R: Dick Hyland, Frank Wilton, Hyland carries the ball

(Stanford University Quad Yearbook Class of 1927)

Scoreless Third Quarter

The third quarter began with an exchange of punts. Then Hoffman threw long to Shipkey to the Alabama 30. Short passes and fake reverses moved the ball to the nine. On fourth down, Stanford's frustration continued when Bogue tried a field goal but missed again.

A poor punt gave Stanford excellent field position at the Bama 30 late in the third quarter. But a 15y holding penalty set the Cardinal back. That forced Hoffman to pass, and QB Emile "Red" Barnes picked it off for Bama on his 15 as the period ended.

The fourth quarter opened with Barnes punting to the Stanford 42. Frank Wilton launched a rainmaker of a punt right back to the Bama 17 where Shipkey recovered Archie Taylor's fumble. With Cardinal fans expecting at least a field goal to clinch the victory, Warner's men soon faced fourth-and-one at the 7. Wade quickly replaced 165lb Archie Taylor with 200lb Molton Smith to help clog the middle. Stanford snapped the ball to Hoffman, who handed it to Bogue on a reverse, but Bama was ready and tackled him short of the line to gain.

On the next play, "the little Tide leader" (Barnes) broke loose off his right tackle to midfield. But he fumbled on the next play, and Swan recovered for Stanford.

Alabama got the ball back when Lewis fumbled, and Smith recovered on the Bama 30.

Then the unexpected happened. The Tide started rolling! They advanced to Stanford's 45 only to lose the ball on a fumble that Walker recovered. That set up the play that turned the tide for the Crimson Tide.

Blocked Kick Leads to Bama Touchdown

Wilton dropped back to punt on fourth down but not far enough. When the ball was snapped, the Tide's two middle men wedged Stanford's left guard and center. Tide lineman Clark Pearce perfectly timed his drive through the hole and blocked the kick with his chest. The pigskin bounded all the way back to the 14 where Wilton recovered it. Since it was fourth down, Alabama took over at that spot with three minutes to play.

Wade sent in 170-pound FB Jimmy Johnson, who had been injured with a dislocated shoulder and had not played the entire game. It proved to be a wise substitution. Johnson was dependable in the clutch, and Wade felt the team would respond to his presence.

Winslett hit the line for 3y. Johnson bowled his way for a first-and-goal at the four. Twice more Winslett crashed into the line only to be stopped short. Finally, Johnson smashed over right guard to make it 7-6.

After the game, Barnes said, "Jimmy Johnson gave the team strength to rally. He could still be running and only the Pacific Ocean could stop him."

Johnson replied, "It was the line which opened up a hole as large as a wagon truck, and it only remained for me to run through that hole."

Bama Uses Trickery to Tie Score

Let Warner describe what happened next.

"With the score now at 7-6 and Stanford leading, Alabama would need a conversion kick to even the score. And my counterpart, Wallace Wade, was ready for this eventuality. He had set up a play which was designed to relieve the game's tension on the man who would be kicking the point-after conversion. And in this situation, it was Herschel Caldwell.

"As Alabama lined up to attempt the conversion kick, with Winslett kneeling on one knee to hold the ball for Caldwell's placement, an ever-ready Stanford defense was tensed for the charge to block the kick.

"At that point, Junie Barnes, the Tide captain and quarterback, yelled out: 'Signals off.'

"Suddenly, the Stanford players began to relax. Yet it was at this same time that the Alabama center snapped the ball to Winslett who spotted the ball, and Caldwell booted a perfect kick to add the extra point and make it a tie game at 7-7.

"A minute later, when the final gun sounded, the Stanford players walked off the field highly embarrassed."

Winslett said later, "I think Coach Wade had thought up the play. That was the only time we used it."

FINAL SCORE: STANFORD 7 ALABAMA 7

Postgame

From the Associated Press game account the next day: "Twice in two successive New Year's Day appearances in the Rose Bowl, the lads from the South have risen to real heights, last year to win from Washington and this year to hold the mighty Cardinals, bosses of the Pacific Coast Conference, to an even break."

Plans were made for a parade to welcome the team home. Merchants closed their establishments, and money was solicited to cover arrangements. A committee was formed to decorate the city.

When the team arrived in Tuscaloosa, the Alabama Million Dollar Band led a parade with the players following in student-drawn wagons.

Dr. George Denny, the university president who had made football a prime recruiting tool for the school, spoke for many Alabamans when he said, "I come back with my head a little higher and my soul a little more inspired to win the battle for this splendid Anglo-Saxon race of the South."

Alabama Governor Bibb Graves proclaimed, "The hearts of all of Dixie are beating with exultant pride. We are here to tell the world that the Crimson Tide is our Tide and an Alabama troop of heroes. It upheld the honor of the Southland and came back to us undefeated. It fought the greatest fight ever fought on an athletic field."

The praise of Fred Digby, sports editor of the New Orleans Item, was typical of the accolades heaped on the Crimson Tide.

"The Alabama team brought new glory to the South and Southern football when it came from behind to tie the Stanford Cardinals at Pasadena on Saturday. Almost every expert in the east and west thought Stanford was too good for the Crimson Tide … But these experts worked along the line of thought that eastern and western football is superior to the southern brand. The result of the two Rose Bowl games in which Alabama has figured … proves a point we have been trying to make for years. Football as played in the south is of as high caliber as football played anywhere. The entire south should be proud of the Alabama team, for it exemplifies the spirit of the southland."

Reference

Stanford University Quad Yearbook Class of 1927

Big Bowl Football: The Great Postseason Classics, Fred Russell and George Leonard (1963)

The Color of Life Is Red: A History of Stanford Athletics 1892-1972, Don E. Liebendorfer (1972)

The Crimson Tide: A Story of Alabama Football, Clyde Bolton (1973)

Bowl, 'Bama, Bowl: A Crimson Tide Football Tradition, Al Browning (1987)

Pop Warner, Football's Greatest Teacher: The Epic Autobiography of Major College Football's Winningest Coach, Glenn S. (Pop) Warner, Edited by Mike Bynum (1993)

Wallace Wade: Championship Years at Alabama and Duke, Lewis Bowling (2010)

Sixteen and Counting: The National Championships of Alabama Football, ed. Kenneth Gaddy (2017)

Stanford University Quad Yearbook Class of 1927

Big Bowl Football: The Great Postseason Classics, Fred Russell and George Leonard (1963)

The Color of Life Is Red: A History of Stanford Athletics 1892-1972, Don E. Liebendorfer (1972)

The Crimson Tide: A Story of Alabama Football, Clyde Bolton (1973)

Bowl, 'Bama, Bowl: A Crimson Tide Football Tradition, Al Browning (1987)

Pop Warner, Football's Greatest Teacher: The Epic Autobiography of Major College Football's Winningest Coach, Glenn S. (Pop) Warner, Edited by Mike Bynum (1993)

Wallace Wade: Championship Years at Alabama and Duke, Lewis Bowling (2010)

Sixteen and Counting: The National Championships of Alabama Football, ed. Kenneth Gaddy (2017)