Clash of Titans

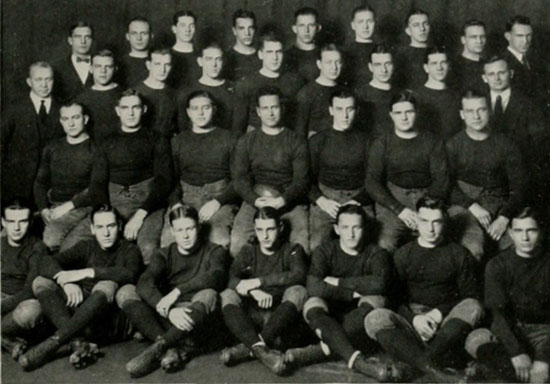

1922 Notre Dame football team (University of Notre Dame Dome Yearbook 1923)

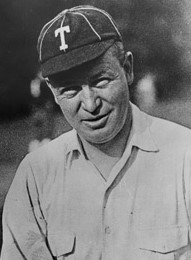

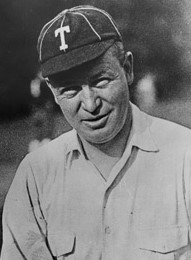

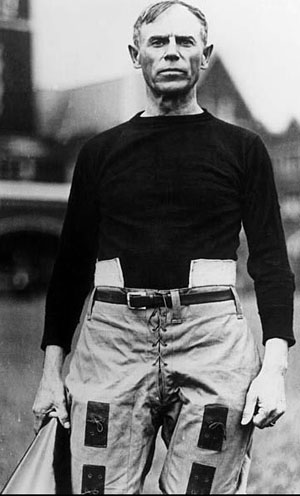

L-R: Knute Rockne, Bill Alexander, John Heisman

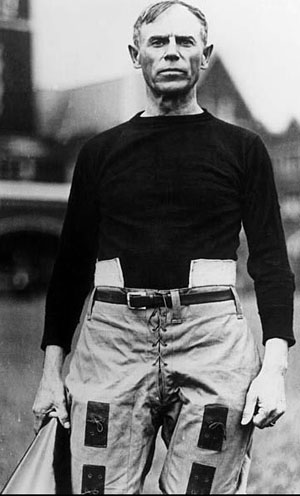

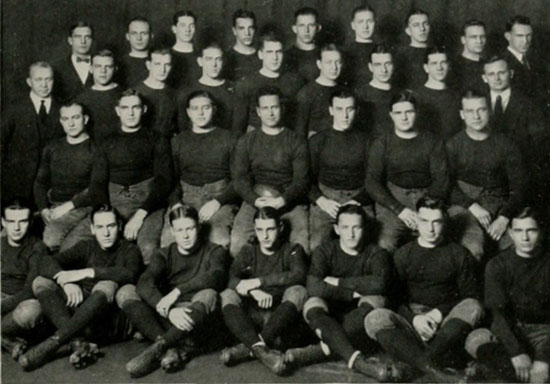

1922 Georgia Tech football team (Georgia Institute of Technology Blueprint yearbook (1923)

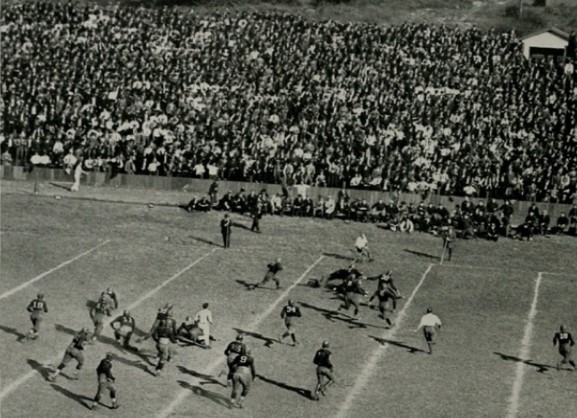

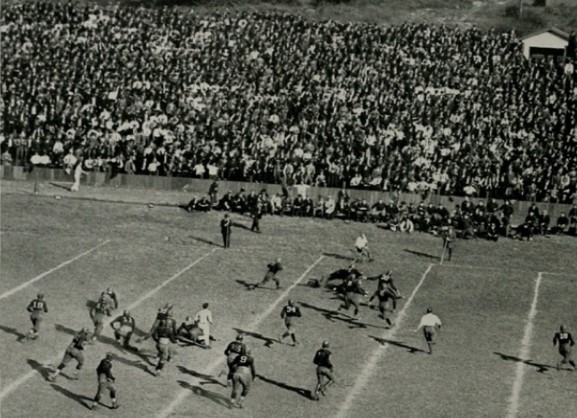

Notre Dame-Georgia Tech action (University of Notre Dame Dome Yearbook 1923)

More Notre Dame-Georgia Tech action (University of Notre Dame Dome Yearbook 1923)

Games featuring a future Hall of Fame coach on each sideline.

October 28, 1922: Notre Dame @ Georgia Tech

Knute Rockne vs Bill Alexander

Knute Rockne became head coach at his alma mater, Notre Dame, in 1918 at age 30. After a 3-1-2 season his first year, the Fighting Irish went 9-0 each of the next two years and then 10-1 in 1921.

After winning their first four games in 1922, the "Fighting Irishmen" (as some articles called them) prepared for Notre Dame's first game in the "Deep South" against the Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets in Atlanta.

In his quest to make football a financial asset for his university and build up a nationwide fan base (especially among Catholics), Rockne scheduled a game at Georgia Tech for the 1921 season only to have the Faculty Board of Control of Athletics veto the arrangement. Rockne had become friends with Georgia Tech coach William Alexander at national coaching meetings.

1922 Notre Dame football team (University of Notre Dame Dome Yearbook 1923)

The game was seen as a great opportunity to show the strength of southern football. Craddick Goins wrote in The Atlanta Constitution, "It is southern football's greatest opportunity...It will mean the greatest possible impetus to football in this section." He continued, "Followers of Tech teams of the past few years have been fairly well agreed that the Tech team is almost unbeatable on its Grant field. This view seems to be well taken for the game of the ordinary type, but Notre Dame has a team far from the ordinary type, and its game here will be far from the ordinary kind...It was for the fixed purpose of adding Tech's scalp to its long pelt that the Indianans consented to come to these parts, and the magician [Rockne] will have his team instructed to show all of its stuff."

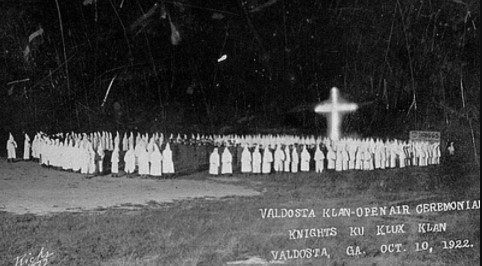

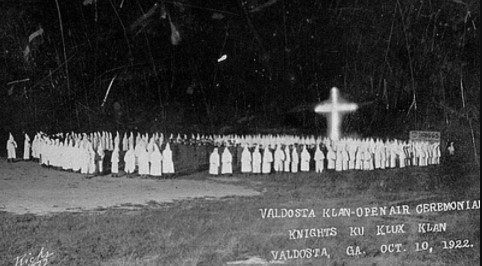

The Irish would be traveling to a hotbed of the Ku Klux Klan. After disintegrating in 1871 following the Civil War, the Klan reemerged in 1915 at Stone Mountain GA, which depicts images of Confederate leaders. The 20th century version of the Klan targeted not only Blacks but Jews, Catholics, and immigrants. Thomas Watson, one of Georgia's U.S. Senators, made anti-Catholic utterances part of most of his campaign speeches, demeaning priests and the pope.

Some Notre Dame faculty and alumni criticized Rockne was taking too large a risk. A lopsided defeat would humiliate the school and, by extension, many Catholics, especially those in the South. If ever there was a must-win for the Irish, this was it.

Even though the Klan had a significant presence in Indiana, Rockne wasn't sure how to prepare his players for the reception they might receive in Georgia. He had even been cautioned by some administrators not to schedule Georgia Tech. Knute decided not to lecture his team about the KKK presence in Georgia. Instead, he warned them about the unsettling Rebel yells they would hear from the stands before and during the game.

L-R: Knute Rockne, Bill Alexander, John Heisman

Tech's fifth-year coach, William "Bill" Alexander, had quickly established a reputation as a tough taskmaster who produced winning teams. He played end and quarterback at Georgia Tech under Coach John Heisman in 1911-12. Heisman appointed him captain of the "scrubs." Bill finally played long enough in two games his senior year to win a letter.

When Alexander graduated with a degree in civil engineering, Heisman kept him as an assistant coach. Bill became head coach in 1920 following Heisman's departure to the University of Pennsylvania.

Alexander, "the youngest coach in major college football" (Georgia Tech Technique newspaper), led the Golden Tornado (as they were more commonly called at the time) to 8-1 records in his first two seasons–good enough to tie for first in the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association. His 1922 aggregation won their first three games, then lost at Navy the week before Notre Dame's visit.

Alexander had already gained a reputation as a tough taskmaster. He often bullied his players, but while they may have hated him on the field, they idolized him off of it. Bobby Dodd, who was one of his assistants and would succeed Bill as Tech coach in 1945, said of him, "He growled, snapped and carried on all over the place, but underneath it all, he was in your corner in any emergency."

1922 Georgia Tech football team (Georgia Institute of Technology Blueprint yearbook (1923)

Rockne usually gave one emotional locker room speech per season and chose the Tech game for 1922. "We've come a long way down here into the South to play this game. We're meeting a great team in Georgia Tech, the greatest in the South. We're playing in a climate that is warm and new to us and that may gave us trouble. We're a young, green team. But now I want you to show what you're going to do for Notre Dame and for me and for yourselves. And remember, I don't want you boys to be the kind who are willing only to go out and cheer for Notre Dame. I want you to go out there this afternoon and live for Notre Dame. Remember that Georgia Tech will be playing this afternoon not only for Tech but for the honor of southern football."

Rockne continued: "You know, I could stand the disappointment and criticism that would come from defeat today. I could stand the criticism that would come in the newspapers, from the football writers, from some of the alumni and the people back home in South Bend ... but this is the sort of thing that makes this game mean a lot to me. This is the reason why I don't want to go back home tomorrow and have to admit that we failed."

If that wasn't dramatic enough, Rockne took a crumpled telegram out of his pocket. After staring at the words on the paper, he read aloud: "PLEASE WIN THIS GAME FOR MY DADDY. IT'S VERY IMPORTANT TO HIM." "It's from Billy," revealed Knute, referring to his six-year-old son who had become the de facto team mascot. "He's very ill and is in the hospital." Some players began to cry; others jumped up and vowed to blast Tech.

Notre Dame-Georgia Tech action (University of Notre Dame Dome Yearbook 1923)

Both teams counted on injured players participating in the contest. Rockne hoped "sophomore flash" Jim Crowley would be able to play but, if not, Elmer Layden would take his place at left halfback. Adam Walsh would start at center in place of "scrappy" Bob Regan, a lighter man who was bothered by an injury. Tech captain and star "Red" Barron was banged up but, as one writer put it, "wouldn't miss this game if he had seven different varieties of charley horse and a broken leg." His courage and dedication to the team would be "rewarded" with the most miserable afternoon of his football career.

The crowd of 18-20,000 that filled every seat and standing room area at Grant Field on a clear but somewhat warm fall day saw an intense struggle in which the home team outplayed the visitors—according to many reporters—but did not win because of their own miscues.

As expected, the game featured hard-hitting with multiple stoppages of play each quarter for injuries. Four turnovers marred the first quarter in which neither team threatened until late in the period when Tech reached the ND 28. A penalty blunted the Tornado advance. So Jimmy Brewster drop-kicked a field goal from the 30 to put Tech up 3-0.

After the teams exchanged punts, Paul Castner punted 40y to Barron, who fumbled, Fod Cotton recovering for Notre Dame on the 22. The Irish took advantage of the break to score the game's first touchdown. Don Miller and Jim Crowley each gained four and Castner five for a first down at the nine. Three more runs made it 4th-and-goal from the four. So QB Harry Stuhldreher threw a pass to Castner in the end zone. Paul kicked the extra point to make it Notre Dame 7 Georgia Tech 3

Late in the second period, Tech nosed into Irish territory on a pass interference penalty and a 10y Brewster run to the ND 45. Two plays later, Barron hit Pinkey Hunt with a pass to the 22. But Barron fumbled again on the next play, and Gene Mayl recovered for Notre Dame to end the threat.

The Irish missed an excellent chance to add to their lead. Eddie DeGree blocked Brewster's punt, the ball rolling out of bounds on the Tech 40. But on the first play, Barron got some revenge by intercepting a pass. After forcing a punt, ND started a sustained drive from its 45. Tech thought they stopped it, but an offside penalty on a punt gave Tech a first down at the GT 48. Three runs advanced the chains before Castner got 15 around left end, "evading a half dozen Tech tacklers" to the nine. But the Yellow Jackets dug in and held the Irish to 4y on three runs before an incompletion turned the ball over on downs. The period ended with Notre Dame on the Tech eight after driving from their own 27. The key plays were passes - 14y Crowley to Castner and 27y Castner to Miller. An incompletion ended the period.

More Notre Dame-Georgia Tech action (University of Notre Dame Dome Yearbook 1923)

Miller fumbled on the first play, and Tech recovered on the five. After running the ball once, Tech punted to Stuhldreher who returned 10y to the GT 40. This time the Irish would not be denied, scoring a touchdown to salt the game away. Passes again proved Tech's undoing. Caster to George Vergara 20y. Castner to Miller for another 20 to the five. Tech gave ground grudgingly, but on third down from the 2' line, Stuhldreher rammed over up the middle. Castner's kick failed. Notre Dame 14 Georgia Tech 3

According to an old story, the term "Hail Mary Play" started in this game long before 1975 when Dallas Cowboys Catholic QB Roger Staubach threw a long desperation pass to Drew Pearson in the last seconds to win a playoff game against the Minnesota Vikings.

The 1922 story says Notre Dame lineman Noble Kizer asked his Fighting Irish teammates to pray before the fourth-and-goal play mentioned above in which Stuhldreher threw a touchdown pass. Later, on third-and-goal, Notre Dame prayed again, and Stuhldreher scored the second touchdown. According to Jim Crowley, Kizer said, "Say, that Hail Mary is the best play we've got."

The 1922 story says Notre Dame lineman Noble Kizer asked his Fighting Irish teammates to pray before the fourth-and-goal play mentioned above in which Stuhldreher threw a touchdown pass. Later, on third-and-goal, Notre Dame prayed again, and Stuhldreher scored the second touchdown. According to Jim Crowley, Kizer said, "Say, that Hail Mary is the best play we've got."

Going for it on fourth down, the Jackets moved after the kickoff to their 47. But Barron's bad day continued with yet another lost fumble. After the Irish used up some time, Tech got the ball back and thrilled the partisans with their most spectacular play of the game. Jack McDonough connected with T. M. Murray for 50y to the ND seven. But with Tech on the doorstep of the end zone, would you believe it? Two plays later, Barron fumbled one last time, and Notre Dame recovered. The game ended a few minutes later. For the first time in nine years, Tech had suffered two consecutive defeats.

FINAL SCORE: NOTRE DAME 14 GEORGIA TECH 3

FINAL SCORE: NOTRE DAME 14 GEORGIA TECH 3

Rockne said the game was one of the cleanest, hardest-fought contests his team had ever taken part in, and he was delighted to have won and to have had the opportunity of coming South. He was high in his praise of the Tech team and was looking forward to the two teams' meeting in 1923 in South Bend.

Notre Dame took home almost $7,000 as its share of the ticket sales to 13,828 white spectators and 18 Negroes. ($7,000 extrapolates to $105,000 today.)

The Augusta (GA) Chronicle article gushed: "It is the greatest visiting team that has ever played on Grant Field, and Georgia Tech has no alibis to offer for her defeat. ... It was the Navy game all over again. ND's running plays were stopped cold, but their overhead game spelled Tech's defeat.

When the Notre Dame team returned to South Bend, there waiting for them at the train station with a large contingent of students was little Billy Rockne who was "rushing up, whooping and hollering" as Crowley recalled. "You never saw a healthier kid in all your life. He hadn't been in a hospital since the week he was born." Rockne and his players "were carried several blocks on the shoulders of cheering students."

References:

Rockne: Idol of American Football, Robert Harron (1931)

Great Football Coaches of the Twenties and Thirties, Tim Cohane (1973)

The Ramblin’ Wreck: A Story of Georgia Tech Football, Al Thomy (1974)

SEC Football's Greatest Games: The Legendary Players, Last-Minute Prayers, and Championship Moments, Alex Martin Smith (2018)

Rockne: Idol of American Football, Robert Harron (1931)

Great Football Coaches of the Twenties and Thirties, Tim Cohane (1973)

The Ramblin’ Wreck: A Story of Georgia Tech Football, Al Thomy (1974)

SEC Football's Greatest Games: The Legendary Players, Last-Minute Prayers, and Championship Moments, Alex Martin Smith (2018)