Clash of Titans

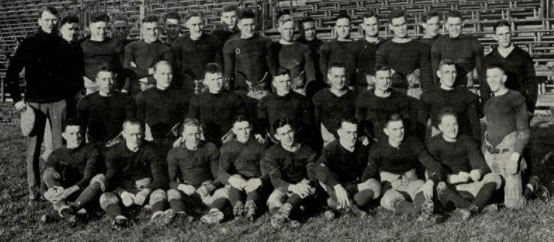

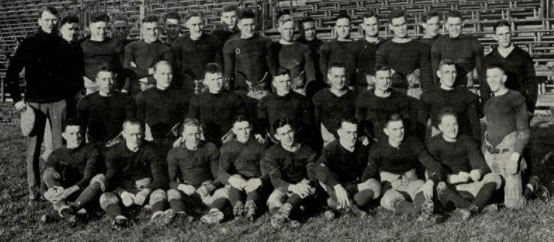

California 1921 football team (University of California Blue and Gold Yearbook 1922)

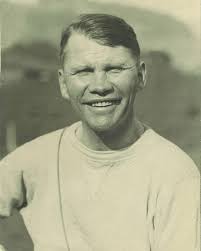

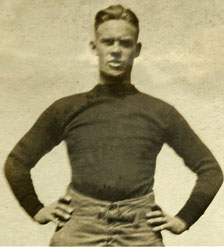

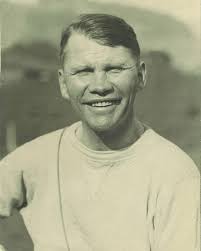

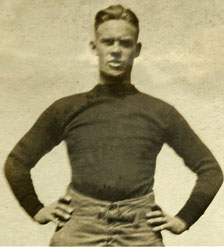

L-R: Andy Smith, Earle "Greasy" Neale, Charles West, Hal Erickson

L: Wayne Brenkert; R: California-Washington and Jefferson action

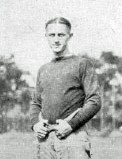

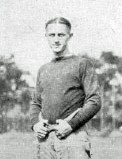

Russ Stein carries for W&J on the muddy field.

Games featuring a future Hall of Fame coach on each sideline.

January 2, 1922: Washington & Jefferson vs California

Earle Neale vs Andy Smith

Some writers called the 1921 California Golden Bears the best team in college football history and dubbed them the "Wonder Team." They had a case. Andy Smith's sixth Cal squad won all nine of their regular season games, seven of which were played in their large (25,000) home stadium. The closest game was a 21-10 victory over Pacific Fleet, a service team that had been formed during World War I. The Bears won all four of their Pacific Coast Conference games, including a 72-3 lambasting of Washington and a 42-7 thumping of archrival Stanford. Cal outscored their opponents 312-33. They finished the regular season with 18 consecutive wins.

The Bears received their second straight invitation to the Tournament of Roses annual "Tournament East-West Football Game" at Tournament Park in Pasadena. Their opponent was from a school no one on the West Coast had heard of: Washington and Jefferson, a private liberal arts college in Washington PA with an enrollment of 450.

California 1921 football team (University of California Blue and Gold Yearbook 1922)

The Tournament of Roses Association voted to invite the Presidents only after Iowa, Cornell, Lafayette, Penn State, and Centre turned them down. Coach Smith gave W&J incentive when he told the press, "We are not looking for easy marks. Bring us something hard to crack." The Presidents had gone Cal one better by defeating all ten opponents on their schedule. The six road victims included Syracuse (17-10), Pittsburgh (7-0), and West Virginia (13-0). W&J outscored its opponents 208-24.

More than once in Rose Bowl history, the West Coast writers put the Pacific Coast host team at a psychological disadvantage by disparaging the visiting team. But no team was ridiculed as much as Washington and Jefferson.

"Who and what is, or are, Washington and Jefferson?" asked one writer. "All I know about Washington and Jefferson," wrote another, "is that they're both dead." Still another guessed that Washington and Jefferson were two different colleges that had merged their teams to give California a bigger challenge. The Presidents were called "Willie and Jake" and "Whitewash U."

Some questioned the credentials of W&J coach, Earle "Greasy" Neale, who played right field for the Cincinnati Reds in the 1919 World Series against the infamous Black Sox. He left the Reds when football season started to coach the Presidents beginning in 1921.

L-R: Andy Smith, Earle "Greasy" Neale, Charles West, Hal Erickson

The 2,500-mile trip to California posed significant challenges for the small school. They could afford to pay for only eleven players from the 26-man roster to travel by train. The athletic director, R. M. Murphy, didn't want to spend college money on his own ticket. So he mortgaged his house to pay his fare.

Everything had to go just right for the plan to succeed. But one of the chosen eleven, C.L. Spillers, came down with pneumonia and had to be left in Kansas City for treatment. What to do now? As luck would have it, reserve player Ross "Bucky" Buchanan stowed away on the train and was given Spillers' ticket when he was discovered. The Presidents arrived in Pasadena December 30.

Another President, Hal Erickson, had already played in the Tournament of Roses game when he was a member of the Great Lakes Navy team in 1919. The W&J players were generally older than the average college player, and Cal fans claimed the Eastern college's academic requirements were far below their school's.

Featured Player

Washington and Jefferson QB Charles "Pruner" West was the first Black player to appear in a Rose Bowl game. He normally played halfback but moved to quarterback (blocking back) for the game in Pasadena.

This exceptional athlete became a two-time collegiate Pentathlon Champion and earned a spot on the 1924 Olympic team. However, an injury kept him from participating.

He signed with the Akron Pros team after graduating from Washington and Jefferson in 1924 but didn't play for them. Instead, he decided to retire from athletics and attend Howard University Medical School in Washington D.C.

West was one of four men inducted into the Rose Bowl Hall of Fame in 2018, joining teammate Russ Stein, who was inducated in 1991. |

|

Neale kept his team in "the pink of condition by frequent drilling on a snow covered gridiron" on campus. The day before the game, Greasy said, "We do not say we are going to beat Andy's crew, and we don't say we are not. We are going to do all our playing on the football field. I've a bunch of fighters, and fight comes pretty near being 60 per cent of a football game. ... The condition of the field will not greatly affect the Washington and Jefferson team as they have played on both muddy and dry fields this season with excellent results. ... The team that ... gets the breaks will win the game."

Coach Smith sounded a different tone. "We ought to win by two touchdowns. Less than that will not satisfy me. And it may even go to twice as many. My team has really not been extended on the Pacific coast this season, and I look to see them uncover the same wonderful game that they showed against Ohio State one year ago." Andy added, "The condition of the playing field will tend to keep scoring at a minimum, and the strong defense of the W&J team is well known. However, my men can overcome these obstacles. They will win."

Heavy rains all day January 1 made the field muddy. And threatening skies the day of the game did not deter a record crowd of 40,000 from filling the stadium, including a large contingent of W&J alumni led by the school's Acting President. Ticket prices were $2.75 and $5.50 (equivalent to $44.50 and $89.37 today).

On the other side, all eyes were on W&J's giant tackle and captain Russell Stein, who was selected for Walter Camp's annual All-American eleven. He "towered over the other players on the squad by several inches." Sometimes Neale called for Stein to carry the ball. Despite Stein's presence, the Bears outweighed the Presidents by six pounds per man.

With no substitutes, the Easterners, a 14-point underdog, could not afford a serious injury. Could they continue to compete as fatigue set in during the fourth quarter? The answer was a resounding yes!

Although no rain fell during the game, the muddy field, ankle-deep in spots, gave a decided edge to the defenses. The teams battled to a scoreless tie in the first quarter in which the most exciting play was negated by a penalty.

In a common move in that era, California won the toss and elected to kick off. Coach Smith did not start his sensational end/passer Harold Muller. Instead Bob Berkey, "hero of the USC game," took the field for the opening kickoff. Muller was better in the passing game, but Berkey excelled at getting down under punts and making "sensational tackles."

|

Featured Player

California E Harold "Brick" Muller was the first player from the Western United States to earn first team All-American honors. He received the recognition in both 1921 and 1922 after earning a third-team berth in 1920. As a three-year starter, Muller, accompanied by six other classmates from San Diego High School, contributed to the Bears to a 27-0-1 record from 1921-22-23. Muller also excelled in track and field with the high jump being his specialty. He helped California win the Intercollegiate Association of Amateur Athletes of America championship in 1921, 1922, and 1923. The Bears also won the second NCAA Track and Field Championship in 1922. Muller won a silver medal at the 1920 Olympics in Antwerp, Belgium, clearing 6-2 2/4 in the high jump competition. Miller was voted into the National Football Foundation Hall of Fame in 1951. |

Brick Miller |

Starting from their 25, the Presidents, "playing straight, old-fashioned football without any frills" but from varied formations, immediately tore holes in the Cal line and skirted the ends to move quickly across midfield. As the W&J rooters went wild, Cal called timeout. When play resumed, the Presidents gained another first down at the 40. Three plays later, Wayne Brenkert ran from punt formation through the line and dodged the entire defense for 36y to the end zone. But the officials–from various parts of the country–brought the ball back and penalized W&J for offside.

After HB Hal Erickson gained 10y, Brenkert threw a long pass that Archie Nesbit intercepted and returned 38y to the W&J 36. But two offside penalties forced Cal to go into punt formation. Instead, Irving "Crip" Toomey threw an incompletion to turn the ball over on downs. The game descended into a punting duel for the remainder of the period as the Presidents stopped everything that the Bears ran and threw at them. Cal enjoyed a marked superiority in the punting game with Nisbet outkicking Brenkert on every exchange.

L: Wayne Brenkert; R: California-Washington and Jefferson action

Neither team came close to scoring in the second period. The only consistent gainer on either team was W&J's Erickson. Running from regular formation and also on "criss-cross plays," he repeatedly reeled off gains. "The California tacklers seemed unable to stop him until three or four men had hurled themselves at him." On one carry, Erickson broke into the clear but slipped down with no defenders in his parth. Erickson also somewhat blunted the Cal kicking edge with his punt returns.

With its running game stymied by the stalwart defense and passing hampered by the wet conditions, Cal resorted to punting on second, third, and even first down, hoping for a fumble or interception in enemy territory that might lead to a field goal.

W&J started strong in the second half until a fumble ended the drive. The Bears then made their deepest penetration of the game before a fumble at the W&J 28 turned the ball over. The Presidents drove back into Cal territory before another bobble thwarted the thrust. Receiving the next kick on their 40, the Easterners gained 30y on a pass from Brenkert to Erickson to the Cal 30. But the drive stalled, and Stein tried a 40y field goal that missed.

Russ Stein carries for W&J on the muddy field.

Continuing their game of "we don't want the ball in our territory; you take it in yours," Cal punted right back. Once again, W&J moved close enough to try a three-pointer, but Stein missed again, this time from 45y out. Near the end of the third quarter, Cal rushed punter Brenkert so fast that his punt went almost straight up in the air and out of bounds on the W&J 22. Sensing that this might be their last chance to score, the Bears threw a pass to Toomey, who caught it behind the line of scrimmage. But as he started to run with the ball, two Presidents hit him hard, knocking him back 5y and loosening the ball from his grip. Erickson recovered the loose pigskin to end the last threat for either team.

FINAL SCORE: CALIFORNIA 0 WASHINGTON AND JEFFERSON 0

The final statistics showed Cal with a paltry two first downs to six for the visitors. The Bears, known for their aerial attack, completed only two passes for just 5y and gained a mere 49y of total offense. The Presidents racked up 114y rushing and 23 passing–all on their one completion in four attempts.

Both coaches were philosophical afterward.

Neale: "I am entirely satisfied with the showing my men made. If they had had a few more breaks, they would have won. The Washington and Jefferson team outplayed California throughout and needed only a little luck to prove it in the score. The slippery condition of the playing field was quite a handicap for my team. The work of some of the officials was far from satisfactory to me."

Smith: "My men put everything they had into the game but could not penetrate the Easterners' strong defense on the muddy field. I am sorry the conditions prevented California from using its usual spectacular plays and am convinced that if the game had been played on a dry field, California would have won. I have nothing but praise for the Washington and Jefferson squad. It is a real team and gave us a real battle."

With no Associated Poll until 1936, California and Washington and Jefferson were declared co-national champions along with Lafayette by the Boand System, which used a mathematical formula that he unveiled in 1930 and used to retroactively determine champions back to 1919.

References

66 Years on the California Gridiron 1882-1948: The History of Football at the University of California, S. Dan Brodie (1949)

Great College Football Coaches of the Twenties and Thirties, Tim Cohane (1973)

California 2015 Football Information Guide

66 Years on the California Gridiron 1882-1948: The History of Football at the University of California, S. Dan Brodie (1949)

Great College Football Coaches of the Twenties and Thirties, Tim Cohane (1973)

California 2015 Football Information Guide