Clash of Titans

Games featuring a future Hall of Fame coach on each sideline.

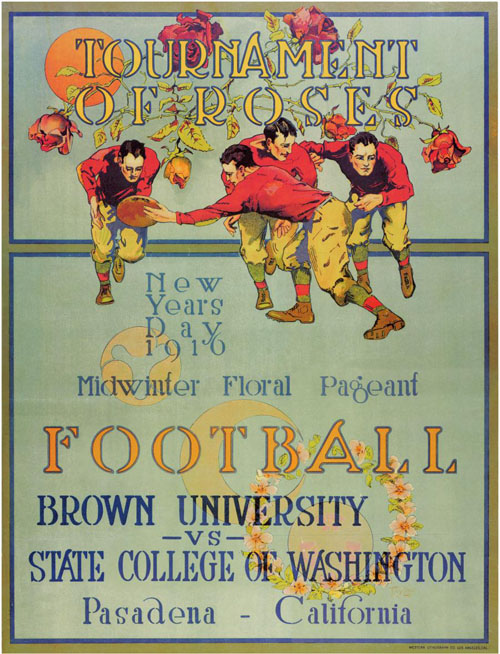

January 1, 1916: Rose Bowl - Brown vs Washington State

Edward N. Robinson vs William Dietz

Evergreen State Has Another Great Team

Edward N. Robinson played halfback for the Brown Bears from 1892 to 1895. After graduating from Brown, he earned a law degree from Boston University.

He started his coaching career at Nebraska, where he compiled a 11-4-1 record over two seasons and led the Bugeaters (they weren't the Cornhuskers yet) to their first championship in the Western Interstate University Football Association.

Robbie then coached at his alma mater from 1898 to 1901 in the first of three separate stints at Brown. After a year at Maine, he returned to Brown for four more years before leaving for Tufts in 1909.

1910 found Robinson back at Brown to start a streak of 16 years that would earn him a spot in the College Football Hall of Fame in 1955. His total record at Brown was 140-82-12 at a time when the Northeast was the power region in college football. Robinson remains the coach with the most wins in Brown football history.

One of his players at Brown was Wallace Wade, who would lift Alabama football to national prominence from 1923-30 before having similar success at Duke from 1931-41 and 1946-50. Wade recalled, "Coach Robinson taught me a lot about football. He was a good coach who stressed fundamentals like blocking and tackling, and he was a good organizer. Many things I learned under Coach Robinson I used later in my coaching career. I must have thought a lot of him because my brother Mark had already played for him at Brown, and he persuaded me to go there."

Edward N. Robinson, William Dietz, 1916 Rose Bowl Program

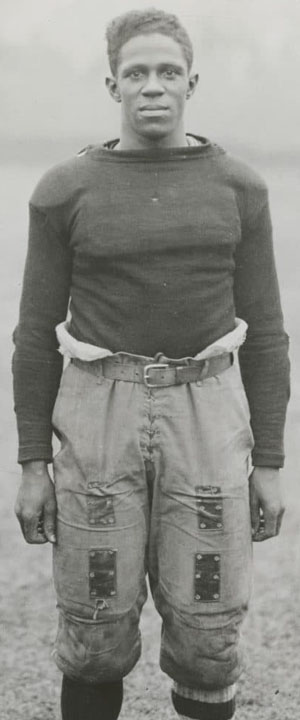

Featured Player

Fritz Pollard was the best player on the 1915 Brown team. He was also the first Black football player at the school. Pollard attended Lane Tech High School in his native city of Chicago where he played football, baseball, and ran track. He majored in chemistry at Brown, where he was one of only two Black students on campus. On the gridiron in 1916, he would become the first Black player on Walter Camp's annual All-American teams. Camp called Pollard "one of the greatest runners these eyes have ever seen."

Tennessee native Wade, who played guard and blocked for Pollard, called him "a great runner. He ran with considerable drive and force, and he changed directions very well." Wade especially liked Pollard's "cross-step dodge," in which Pollard would fake to the inside or outside, then cross one foot over the other, all the while moving forward.

When he became a coach, Wade stressed to his backs and ends the importance of constantly moving forward. He didn't want his players to move sideways or backward, even to elude tacklers. "Fritz was one of the best runners that I've known in all my football experience," Wade recalled. "I've studied Grange and all those fellows. Seen Grange play. Fritz could go up with any of them."

Pollard played pro football with the Akron Pros, leading them to the American Professional Football Association championship in 1920. The next year, he became the co-head coach of the team while still playing. |

|

| Pollard was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1954. He was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame posthumously in 2005. |

|

When Wade's father found out that Pollard was on the Brown team with his son, he traveled to Providence and threatened to take Wallace out of school if Pollard remained. But Wallace stood up to his father and said that Fritz was a good person and good teammate. Coach Robinson talked to Mr. Wade and persuaded him to leave Wallace in school.

Years later, Wallace Wade recalled the unique relationship. "I was proud to have Fritz as a teammate and friend. He was a good chap. We would eat together at the training table."

Years later, Wallace Wade recalled the unique relationship. "I was proud to have Fritz as a teammate and friend. He was a good chap. We would eat together at the training table."

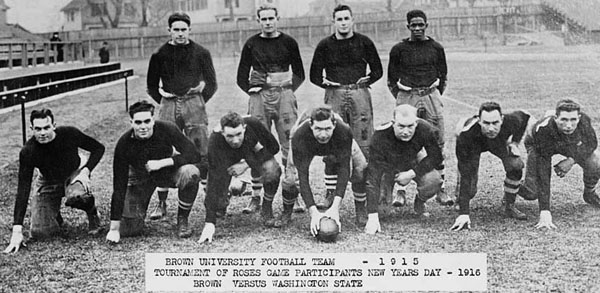

Brown's 1915 season certainly had its ups and downs. After beating Rhode Island State, the Bears tied Trinity College 0-0 and lost at Amherst 7-0. A 33-0 beatdown of Williams followed before a home loss to Syracuse, 6-0.

A 46-0 pasting of Vermont preceded the big game with Yale in New Haven. The Bears claimed one of their signature victories of the season, 3-0. But the up was again followed by a down, a 16-7 loss to Harvard in Boston.

The season ended–or so everyone thought–with a 39-3 thumping of the Carlisle Indians, who finished 3-6-2 in their first season after the departure of legendary coach Pop Warner.

Wallace Wade is the right guard.

Meanwhile, decisions were made at the other end of the continent that would give Brown the chance to play one more game.

Citizens in Pasadena CA began "The Tournament of Roses" on New Year's Day of 1890 to attract visitors to their beautiful city during the winter months when the roses were in bloom. The festivities included a parade of decorated carriages and a series of games like footraces, tug-of-war matches, and jousts. The annual event continued through the 1890s with competitions like chariot racing and bicycle races.

Unfortunately, the Tournament's sports events did little to attract visitors. People came to town primarily to see the parade. So on January 1, 1902, the tournament administration staged a football game as the major attraction. They matched the best team on the West Coast, Stanford, against a visiting team, Fielding Yost's Michigan Wolverines who had won all ten games, outscoring opponents 501-0.

The game was successful in that it attracted a crowd estimated at 8,500 that overflowed the Tournament Park stadium. But Michigan slaughtered Stanford 49-0, proving beyond doubt that no West Coast teams were in a class with the top teams from the Midwest and Northeast.

Despite earning a profit of over $3,000, the plan to host an annual football game was set aside until West Coast football improved to a point where the top teams could compete with visiting teams.

That day came in 1915 after the Tournament Park stadium had been enlarged to accommodate the growing crowds for the chariot races. So the gridiron matchup was resurrected for January 1, 1916.

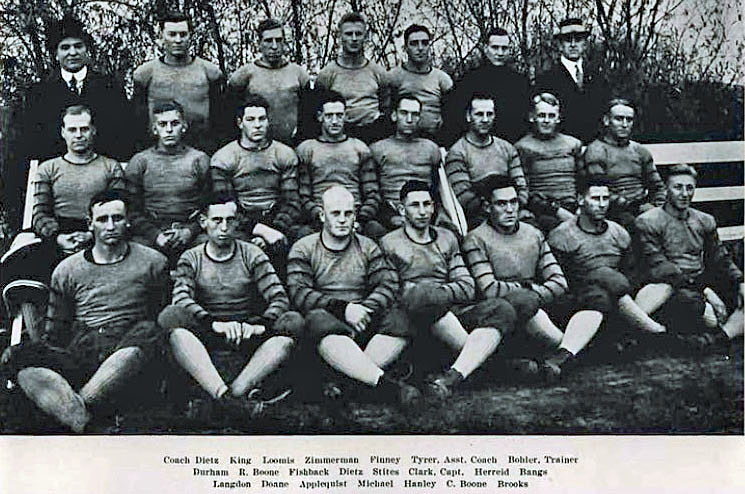

Washington State 1915 team; Coach William Dietz is at the left end of the back row.

Both Washington and Washington State were undefeated. They didn't play each other because a number of Northwest schools, including Washington State College, refused to play Washington in order to derail the dynasty that Coach Gil Dobie had developed. He hadn't lost a game in eight seasons in Seattle.

One of the reasons the Tournament of Roses committee chose Washington State was that Dobie had abruptly resigned at the end of the 1915 season following repeated clashes with the university president, who felt Dobie was putting football above academics and gaining more popularity on campus than the president. (Dobie would change his mind and return for one more season at Washington.)

The surprising choice for the visiting team was Brown. Even though the Bears' record was just 5-3-1, the committee was impressed by their victories over Yale and Carlisle, both of whom had formidable football reputations that stretched all the way to the West Coast. Michigan and Syracuse were the other two teams that were considered.

The team left Providence for their cross-country journey December 22. Students were excused from morning classes to give them a rousing sendoff. They snake-danced to the Union Station Depot where the traveling party of 26 (21 of them players) boarded the train. Captain Buzz Andrews promised the gathering that the team would bring home "a good long slice of Washington bacon."

The team stopped in Chicago to practice at Northwestern's field. They also stopped at Albuquerque NM on Christmas Day for a brief workout at the University of New Mexico field that was cut short because of the high altitude.

The train arrived in Pasadena at 5 AM on December 27. The traveling party moved into the Hotel Raymond which was owned by a Harvard grad who welcomed them while wearing a football uniform that the university had sent to him.

Practices were held daily at the Horace Mann School, named for the famous educator who was a Brown graduate. Unfortunately, rain fell off and on right through the day of the game.

Fritz Pollard recalled that the team was "entertained very lavishly and were taken to outstanding places in Pasadena and also to all the movie studios and met several of the movie stars of that era." He also remembered that a number of players violated curfew many nights, sneaking back into the hotel via a side elevator.

Wallace Wade recalled that "we had one of the most confident teams ever to play in Pasadena. We took the whole jaunt as a lark, because west coast football was considered to be far inferior to our eastern brand."

That was a big mistake because Washington State had outscored its six opponents 190-10 under new coach William Henry "Lone Star" Dietz, who had played for the immortal Warner at Carlisle and had totally transformed WSC's football program.

Read about Dietz's first year at Washington State ...

Read about Dietz's first year at Washington State ...

When Dietz arrived in Pasadena with his team, he told the press, "Brown will simply wipe the dirt with us." He always regarded optimism as the archenemy of good football.

WSC's preparation for the game was odd. The Cougar players served as extras in the football film Tom Brown of Harvard each morning, then practiced for the bowl game during the afternoon. Each WSC player earned $100—a colossal sum in 1916 when a loaf of bread cost only 8 cents—for the 14 mornings of movie work. During practices, Dietz appeared in his usual unusual debonaire coaching attire: a silk hat, Prince Albert cutaway coat, striped pants, yellow gloves, and a walking stick. Thanks to the two-a-day workouts, Dietz had his tiptop shape for the game.

The national bias against West Coast teams was illustrated by the fact that Brown was considered the favorite for the "Pasadena Tournament of Roses East-West Game" (as it was called until 1923 when the current Rose Bowl Stadium was completed and the name changed).

One newspaper report from Pasadena the day of the game said this: "It is not expected that either team will play up to its midseason form, for the reason that it has been hard to keep the men interested in practice after the season closed Thanksgiving Day. The climate here is very much different to that of either Providence, R.I., or Pullman, Wash. and that will also have its effect on the men.

"The Brown men are chunky fellows who have won their games by line smashing plays varied with forward passes. The Washington boys are more rangy and have a more varied style of attack. The Washington men were strong on offense during the regular season but were rather loose on defense, and Brown men are counting that as a point in Brown's favor for they do not figure that Brown's line plays can be stopped."

To meet the demand for tickets, the Rose Bowl Tournament committee borrowed grandstands from the Al G. Barnes Circus to nearly double the 10,500 seats already installed.

The game plans of both teams were negated when snow fell in Pasadena December 30 for the first time in 13 years. Then a light rain that fell throughout the New Year's morning made the field of play muddy and the ball slippery. The field was covered with a tarpaulin and sawdust early in the morning and seemed to be in good condition in the first quarter. But the steady rain soon turned the field into a quagmire. At kickoff, less than 4,000 people were in the stands although that number increased to 7,000 by halftime. All were huddled under umbrellas and raincoats throughout the game.

The Washington State team had an extra incentive for winning the game. Amid rumors that Coach Dietz would leave for another school, Assistant Coach Tyrer ran onto the field and told the players as they prepared for the kickoff that Dietz would turn down all the offers he had received and coach them again if they beat Brown. The players yelled at Dietz, "You're coming back!"

Washington State players L-R: Art Durham, Carl Dietz, Benton Bangs, Richard Hanley, Ralph Boone

(Washington State Chinook Yearbook Class of 1917)

Scoreless First Half

The Easterners threatened first, using line plunges from its double-wing formation to drive to the WSC four before being stopped. To quote Harry A. Williams in The Los Angeles Times, "Dietz's men here dug their heels into the mud and held magnificently, considering that they were not equipped with ski chains."

Later in the opening quarter, Pollard's interception on his 25 stymied a WSC advance. Brown's offense consisted mostly of end runs while Washington State, though lighter, sought to gain by line plunges.

On punt returns, Pollard, shifty and slippery, would elude two or three westerners but could not escape the rest of the coverage.

The second quarter began with the ball at WSC's 12 after a punt. But that period was a repetition of the first. Neither team could score, although Brown had the ball most of the time.

Junior WSC QB Art "Bull" Durham started calling wide end runs, but the Bear ends were set for them. John Butner and Josh Weeks burst through the interference and downed the runner. However, both ends were hurt and did not play in the second half.

Brown advanced deep into the WSC territory on bucks by H. P. Andrews and C. J. Purdy, a 10y end run by Pollard, a 15y penalty against the defense for pass interference, and a completion to Andrews. But the onslaught bogged down at the six.

Second Half

The tide of battle changed at the beginning of the second half when "a powerful young gent with bulging biceps," Ralph Boone, relieved Richard Hanley at right halfback. Boone would carry the ball three out of every five plays in the second half.

With second string ends playing for Brown, Coach Dietz attacked the edges of the defense. WSC gained 202y on the ground in the second half to only 17 for Brown. WSC drove inside the Brown 15 five times, scoring twice. The Easterners never threatened the entire second half.

The key was the formation Dietz deployed. Two lineman shifted over from the left to the right side, and the backs formed a V-shape behind them. The ball carrier would start toward his right tackle and then veer inside or outside depending on the blocking. Mark Farnum, Brown's 6'2" 220lb tackle who had made some All-American teams, was knocked back three or four yards on nearly every play.

R. B. Ward kicked off forat the start of the third quarter. Durham caught the ball on his 15 and ran it back 20y. Using repeated line plunges, WSC moved the ball deep into Brown territory only to lose it on HB Benton "Biff" Bangs' fumble. Andrews immediately punted back to midfield.

A 50y punt by FB Carl Dietz (no relation to the coach) put the ball in Brown territory, where the rest of the game was played except for three brief trips into WSC terrain.

Boone, Bangs, and Dietz moved the ball relentlessly until Boone drove into the end zone through left tackle from the five to finally break the scoring ice. Durham kicked the point. Washington State 7 Brown 0

The Cougars barged downfield again when they got the ball back but lost the ball on a fumble recovered by Brown at the four.

Toward the end of the third quarter, Coach Robinson yanked his entire backfield. When the backups could make no headway, the original backfield was restored at the beginning of the fourth quarter.

WSC started an 80y scoring drive late in the third quarter that culminated early in the fourth period when FB Carl Dietz put his head down and plowed through the mud to a touchdown. Washington State 14 Brown 0

Durham missed a drop kick field goal try from the 30 late in fourth quarter.

FINAL SCORE: Washington State 14 Brown 0

As the teams left the field, the Cougars were jumping around like maniacs in each other's arms. The Brown men walked through the rain, each man by himself, with their eyes on the ground. They got into their bus and were driven from the park with hardly any man speaking.

The Cougars were especially happy because they pooled their movie earnings and bet on themselves as underdogs. They returned to Pullman fabulously rich compared to the average 1916 college student's wealth.

The Tournament of Roses committee was not happy. The gate receipts were $7,000, of which Brown was paid a $5,000 guarantee while Washington State expenses were almost the same. The net loss was $11,000. While many on the committee were ready to pull the plug on the tournament, the Tournament "strong man," J. J. Mitchell, moved forward on his own, boldly announcing that plans for the January 1, 1917 contest were moving forward.

Pollard, "the gentleman of color and ability," wrote Williams in the LA Times, "hardly performed up to his advance notice. Speed is one of his greatest assets, but the slippery field made it of little use to him. He made some gains but could never break away for long runs. Once or twice, he was trapped behind his own line before he could get up steam and could do nothing but dodge back and forth. He was slippery as the proverbial ebb, and it usually took half the Washington team to bring him down." Pollard gained just 47y in 13 carries.

Brown C Ken Sprague said, "With Pollard's running and Buzz Andrews' passing, we would have been three or four touchdowns ahead on a dry field. The sea of mud which we hardly expected of California changed everything."

Referee Walter Eckersall, a former All-American back at Chicago, said after the game that Washington State "is the equal of Cornell," which was considered the top team in the East because of its 9-0 record. Eckersall continued his praise of WSC: "There is not a better football team in the country. ... This fellow Carl Dietz hits the line harder than any man I have ever seen. The team starts faster and more as a unit than any team in the United States. These Northwesterners must surely be used to playing in mud. I didn't think it possible for men to veer into the line as they did and hold their feet, nor hit as hard and still keep going."

References

The Rose Bowl Game, Rube Samuelsen (1951)

Big Bowl Football: The Great Postseason Classics, Fred Russell and George Leonard (1963)

"The Loser Who Won: The Story of the Legendary Gil Dobie," Robert S. Welsh, COLUMBIA the Magazine of Northwest History, Fall 1987: Vol. 1, No. 3

Wallace Wade: Championship Years at Alabama and Duke, Lewis Bowling (2010)

Brown Football Varsity Lettermen at brownbears.com

2022 Washington State Football Media Guide

The Rose Bowl Game, Rube Samuelsen (1951)

Big Bowl Football: The Great Postseason Classics, Fred Russell and George Leonard (1963)

"The Loser Who Won: The Story of the Legendary Gil Dobie," Robert S. Welsh, COLUMBIA the Magazine of Northwest History, Fall 1987: Vol. 1, No. 3

Wallace Wade: Championship Years at Alabama and Duke, Lewis Bowling (2010)

Brown Football Varsity Lettermen at brownbears.com

2022 Washington State Football Media Guide