Clash of Titans

L-R: Fielding Yost, Amos Alonzo Stagg, William Harper

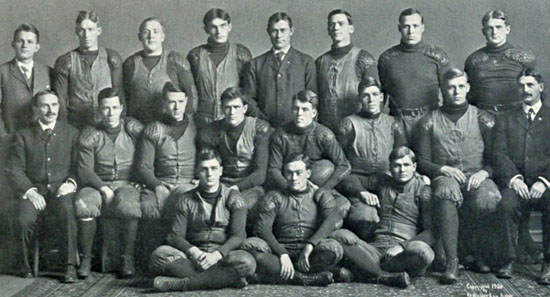

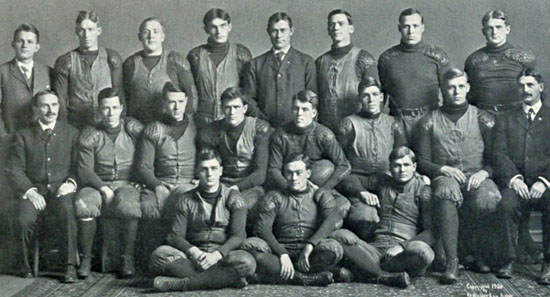

1905 Michigan Wolverines (Michiganensian Yearbook Class of 1906)

Chicago-Michigan 1905 (University of Chicago Cap and Gown Yearbook Class of 1906)

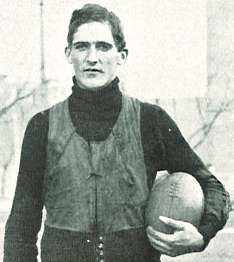

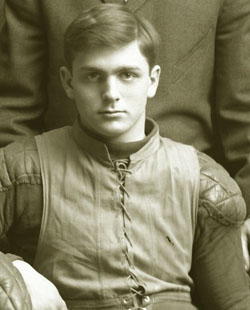

L-R: Michigan players John Garrels, John Curtis, and William Clark; Mark Caitlin of Chicago

Games featuring a future Hall of Fame coach on each sideline.

1905: November 30, 1905: Michigan @ Chicago

Fielding Yost vs Amos Alonzo Stagg

In the early years of the Western Conference (today's Big Ten), the big game was the annual Thanksgiving Day clash between Michigan and Chicago. The 1905 game at Chicago's Marshall Field attracted more interest than any game west of Philadelphia ever had before.

Both teams were undefeated. The Maroons of Amos Alonzo Stagg were 9-0. Fielding Yost's Wolverines were not only 11-0 but had not been scored on all season. Their closest games were 12-0 over Wisconsin and 18-0 over Vanderbilt. Furthermore, Michigan had not lost since the last game of the 1900 season when Chicago won 15-6. Yost, who took over for the 1901 season, had never lost in his 65 games as head coach in Ann Arbor. Only a 6-6 tie at Minnesota in 1903 blemished his record. Included in the streak was a 49-0 trouncing of Stanford in the first Tournament of Roses game on January 1, 1901. Yost's teams had scored 2,746 points to 40 for their opponents!

L-R: Fielding Yost, Amos Alonzo Stagg, William Harper

Chicago enlarged its seating to accommodate 27,000 spectators but could have sold twice that many tickets. 3,000 UM fans journeyed by train to sit in the west stand supposedly reserved for them only to find another 3,000 Chicago fans there too. The crowd included large numbers of women who rooted as enthusiastically as the men.

The stands starting filling two hours before kickoff. Many others viewed the game from the windows of the Home for Incurables across 56th Street from the stadium while others paid exorbitant sums to sit in temporary stands on the roofs of houses across Ellis Avenue. A large number of students without tickets viewed the action from Hitchcock Hall, a male residence hall that was gleefully opened to women for the afternoon.

Among the spectators was a 17-year-old Chicago high school student named Knute Rockne, who rooted passionately for the Maroons, his favorite team directed by his coaching idol.

An estimated $50,000 had been bet on the contest. Scalpers, mostly Chicago students, received upwards of $20 per ducat. Walter Camp, considered the "Father of American Football" and creator of the annual All-American teams, traveled from Yale for the contest. In a precursor to the rooftop bleachers across the street from Wrigley Field, some fans paid to watch from temporary stands atop houses across Ellis Avenue.

Chicago president William Harper, despite being bedridden with the cancer that would take his life in several months, supervised the preparations for the big clash in detail. However, his plan to watch from his son's room in Hitchcock Hall across the street from the stadium didn't materialize because he was too weak that day. Instead, his son described the game to him from a special telephone line installed from the sideline to the residence.

1905 Michigan Wolverines (Michiganensian Yearbook Class of 1906)

The Michigan Yearbook for 1906 admitted this: "On a basis of the season's record, Chicago hardly seemed in Michigan's class and this caused a feeling of overconfidence among the students. There was a general feeling that mere victory over Chicago would not suffice; that the score must be at least 20 to 0. This sentiment communicated itself to the team in spite of the constant efforts of Coach Yost to eradicate it. But the fact was overlooked that Chicago always plays her best game against Michigan."

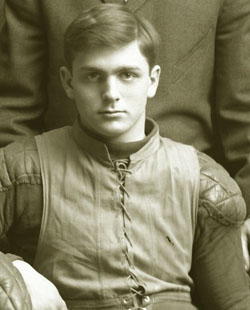

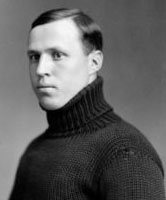

Chicago-Michigan 1905 (University of Chicago Cap and Gown Yearbook Class of 1906)

Featured Player

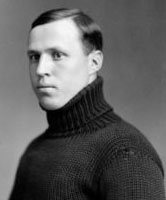

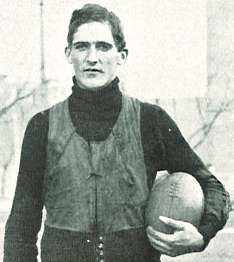

Walter Eckersall was born and grew up in Chicago. He first displayed his athletic talent at Hyde Park High School just two blocks from the University of Chicago.

Small in stature, Eckersall ran the 100y dash in 10.0 seconds, an Illinois record for 25 years. He used that speed to lead Hyde Park to an undefeated football season in 1903. On offense, he called the plays, handled the ball expertly, and punted and drop kicked expertly. He also excelled as a defensive back.

Early in the season, Hyde Park played a practice game against the Wisconsin Badgers varsity and lost by only 24-5.

The final game of Hyde Park's season was a 105-0 trouncing of Brooklyn Polytechnic at Marshall Field to claim the unofficial national high school championship.

Eckersall also was an outstanding fielding and hitting shortstop and a fine pitcher.

Most importantly, Walter was an exceptional leader, as evidenced by the fact that his football teammates voted him captain in both his junior and senior years.

Both Fielding Yost and Amos Alonzo Stagg recruited Eckersall and four of his talented teammates. Wisconsin and Illinois, among many other schools, wanted him. Yost thought he had an edge because he had attended one practice and given the Hyde Park team pointers to prepare for their romp over Brooklyn Polytechnic.

But it took more than that to woo the players away from Chicago. Stagg had opened his athletic facilities to all the Hyde Park athletes for a year and had coached the team throughout the week before the championship game.

|

|

Although newspapers reported that Walter and his teammates were ready to commit to Michigan, he announced no decision until September 12 when he did what his parents wanted him to do – enroll at Chicago.

Eckersall led Chicago to a 25-2-1 record in his three years of eligibility as the Maroons outscored their opponents by 856-66. He made Walter Camp's All-America Team each of his three years of eligibility.

As Chicago's greatest star of the early 20th century, Eckersall was allowed to compete for three years despite making almost no progress toward a degree. This couldn't have happened without the cooperation of Coach Stagg's friends on the faculty.

After his playing days, Eckersall became a sportswriter for the Chicago Tribune and one the most respected football referees in the nation. He selected his annual "All Western Conference" all-star team for the Tribune.

| |

Michigan Loses Its Best Lineman

The game unfolded on a gray 10-degree day with light snow falling intermittently. The two finely-tuned machines played as close a game as any two teams could without tying. The first half devolved into a punting duel between Chicago's sophomore QB Walter Eckersall (12 punts) and John Garrels of Michigan (10 boots). The Maroons crossed midfield three times, the Wolverines only once.

Michigan Yearbook: "It was something of a shock when the despised Chicago line held against the terrific assaults of the blue-clad warriors. A fumble, coming at a crucial moment, spoiled an early chance for Michigan to score. The whole team became confused and bewildered when (LT John) Curtis was put out of the game and other Michigan players were threatened with a similar fate for no apparent reason."

Although downplayed by the UM writer, the expulsion came because Curtis left his feet, lunged, and slammed all of his 215lbs into 5'6" 142lb Eckersall right after he punted, knocking him almost unconscious. So Michigan lost the services of the man Walter Camp had rated as the best tackle in the West. Meanwhile, Eckersall stayed in the game. The umpire who expelled Curtis was a teammate of Yost's at Lafayette College.

At halftime, Harper sent his nurse to the locker room to deliver a personal message telling the team that they "must win this game." Stagg added his own plea to win one for their dying president.

Yost made one substitution for the second half: William Dennison "Denny" Clark for LHB Ted Stuart. The move would prove fateful for the Wolverines.

L-R: Michigan players John Garrels, John Curtis, and William Clark; Mark Caitlin of Chicago

Eckersall Misses Field Goal

Midway through the second half, Chicago recovered a muffed punt by QB Fred Norcross on the UM 40. But the Michigan defense stood strong. So on third down, Eckersall tried a dropkick field goal from more than 45y out and at a bad angle. But a defender partially blocked it. Norcross grabbed the ball at the 10 and returned it 7y.

You couldn't blame spectators on both sides for resigning themselves to a scoreless tie. It would take a mistake by one of the teams to end the scoring drought.

With less than 15 minutes left to play, Chicago was backed up inside its ten by a UM punt and a penalty. Then came the key play of the game, which didn't seem all that important at the time but ultimately led to the only points of the afternoon. It was an astounding turn of events because a player on one of the two well-oiled machines made an individual decision that cost his team the game.

Chicago Gains Field Position Advantage

Back to punt in the end zone, Eckersall evaded the rushers and scampered for a first down on the 22. Decades later, Stagg called it "the most daring play I ever saw in a championship game."

Eckersall soon had to punt again but from a more advantageous position on the field. After two more punts, Michigan started a possession at its 19. As he would do so often during his career when having the ball deep in his own territory, Yost ordered a punt on first down. This time, it was Garrels' turn to take off running around right end, where Chicago's Ed Parry had gotten sucked in.

Garrels sprinted into the clear with only Eckersall standing between him and the goal line. The Chicago star caught up and dived low, grabbing the runner by one foot and wrestling him to the ground at midfield.

But right after seizing the momentum, Michigan gave it right back when FB Frank Longman fumbled and Chicago recovered.

Chicago Gets Safety

Following another punt exchange, Chicago had the ball at the UM 45. After gaining only 3y in two tries, Eckersall punted across the goal line. With two Maroons bearing down on him, William Clark made the fateful decision to try to run it out instead of taking the touchback to put the ball at the 25. He slipped by Arthur Badenoch to get across the goal only to be driven back across the line by Chicago captain Mark Caitlin for a safety. (There was as yet no end zone and no forward progress for runners.) Chicago 2 Michigan 0

Neither team came close to scoring in the remaining five minutes of the game. Although Yost used his arsenal of trick plays, none of them got the Wolverines past midfield. He was denied a championship for the first time in his nine years as a football coach.

When the final whistle blew, hundreds of Chicago fans tore down the fence in front of the stands and rushed the field. Most surrounded their victorious heroes while a smaller group jeered the Wolverines.

2,500 Chicago students and alumni formed an impromptu parade. Led by the band, they marched to President Harper's house and sang the Alma Mater. The celebration continued the next day with a bonfire accompanied by "a nightshirt parade and dance." On Monday night, the university staged an official celebration of the "Big Nine" championship called the "Monster Football Mass Meeting." Numerous alumni, particularly former players, assembled with the students.

Tragic Aftermath

Meanwhile, William Clark was pilloried as the goat who ended Michigan's streak. Camp himself described the ill-advised attempt to run out the punt as "a rank blunder." One newspaper declared: "Clark of Michigan defeated his own eleven." Clark left the team after the game and was missing for a time. He was quoted as saying, "This is horrible. ... I shall kill myself because I am in disgrace." He didn't do so at the time but finally did shoot himself in the heart seven years later. A suicide note to his wife expressed hope that his "final play" would atone for his blunder that cold Thanksgiving Day at Marshall Field.

As sore losers often do, Michigan blamed the officiating and somewhat exonerated Clark. From the class of 1906 yearbook: "It is now conceded by nearly everyone that Umpire Rheinhart made a mistake when he ruled Curtis out of the game, and it can hardly be doubted that it was the latter's expulsion that gave the championship to Chicago. The loss of the game can be directly traced to an error of judgment by one Michigan player but it was his eagerness to win that caused him to err and such a mistake is easily forgiven."

The 1905 UM-Chicago game was in many ways the end of an era. Although the game itself did not provide any examples of brutality and serious injury, winds of change soon swept through college football, involving even the president of the United States. Rules changes made the game less hazardous and tried to regulate a spectacle that many university presidents and faculty believed was threatening the academic integrity of their institutions. One of the casualties of the reform movement was the Thanksgiving Day UM-Chicago clash. The two universities did not meet on the gridiron again until 1918. In that same year, Michigan began playing an annual game with Ohio State.

Reference: Michigan-Chicago 1905: The First Greatest Game of the Century (Journal of Sports History, Vol. 18, No. 2 Summer 1991, University of Illinois Press)

Stagg University: The Rise, Decline & Fall of Big-Time Football at Chicago, Robin Lester (1999)

The Opening Kickoff: The Tumultuous Birth of a Football Nation, Dave Revsine (2014)

Stagg vs Yost: The Birth of Cutthroat Football, John Kryk (2015)

Stagg University: The Rise, Decline & Fall of Big-Time Football at Chicago, Robin Lester (1999)

The Opening Kickoff: The Tumultuous Birth of a Football Nation, Dave Revsine (2014)

Stagg vs Yost: The Birth of Cutthroat Football, John Kryk (2015)