Clash of Titans

Games featuring a future Hall of Fame coach on each sideline.

December 25, 1894: Chicago vs Stanford

Amos Alonzo Stagg vs Walter Camp

Stagg Transforms Chicago

When Amos Alonzo Stagg graduated from high school, his career goal was Christian ministry. But as a Divinity School student at Yale University, he came to realize that his public speaking was not good enough to be an effective minister. So he turned his life in a different direction.

An outstanding pitcher on the Yale baseball team as an undergraduate, Stagg played end on Walter Camp's Yale football teams in 1888 and 1889. The 26-year-old graduate student was the oldest member of the team. He has been described as "a fiery, 155-pound end and halfback."

After several years working for the YMCA in Springfield MA where co-worker James Naismith invented basketball, Stagg was contacted in 1892 by William R. Harper, who had just been hired as the founding president of the University of Chicago. Harper, one of Stagg's professors in the Yale Divinity School, was a proponent of "Muscular Christianity," which preached the spiritual value of sports, especially team sports.

Wanting to install a sports program at Chicago that exemplified the virtues of Muscular Christianity, Harper thought immediately of Stagg as the ideal person to coach the football team and head the athletic department. A yearly salary of $2,500 and a tenured position as an associate professor enticed Stagg to accept the new challenge.

Discouraged when only 12 students came out for the first football practice at Chicago, Stagg shortened practices to attract more players and took the field himself in practice games against high school teams.

Competing as an independent not affiliated with any conference, the Maroons tied crosstown rival Northwestern 0-0 before losing the rematch two weeks later 6-4. Chicago won one of four additional games against other colleges. They split a home-and-home pair with Illinois and lost at Michigan and at Purdue.

Stagg played more sparingly in 1893 as his squad showed marked improvement. They compiled a 6-4-2 record and were outscored by their opponents by just one point, 143-142. Ten of the games were played on the university's new Marshall Field. The most impressive victories came against Northwestern twice and Michigan. The season ended January 1 with an 8-0 victory over a small Catholic school from South Bend IN called Notre Dame.

During 1893, Stagg and one of his former players at Yale, H. L. Williams, published Football, the first book that contained diagrams of college football formations and plays.

With a 2,000-seat grandstand added to Marshall during the 1893 season, the foundation was laid at Chicago for a successful intercollegiate football program. So with the complete backing of President Harper, Stagg became more ambitious in his scheduling for the 1894 season.

1894 Chicago Maroons Football Team (University of Chicago Cap and Gown Yearbook Class of 1895)

Stagg scheduled a whopping 22 games for the 1894 season. But if you discard the meetings with the likes of the Chicago Dining Club, Englewood and Manual Training High Schools, Rush Medical, and two YMCA teams, you get nine games against other college teams.

The last two games against college opponents were the most imaginative of the season. Stagg conceived the idea of a West Coast tour for his squad during the Christmas holidays. While the student editor of the university newspaper saw the excursion as a "traveling advertising organization for the university," the real goal was to make money.

Stagg's Yale mentor Walter Camp became the football coach at Stanford University in California, which had opened in 1891, just a year before the University of Chicago. Somewhat paralleling what Harper had done to attract Stagg a year later, the student manager/ captain of Stanford's fledgling football team wrote to the most famous man in American football, Walter Camp, to ask for suggestions for a coach for Stanford. Camp replied that all the men he would suggest already had jobs at other schools. Instead, he told the student that if Stanford had not obtained anyone by Thanksgiving, he might come himself after Yale's season ended. And that's what happened. Camp coached three "official" games, a win and a tie against the San Francisco's Olympic Club and another tie against archrival California.

For 1893, Stanford hired C. D. Bliss, a halfback for Camp at Yale. He led Stanford to an 8-0-1 record, which was by far the best of the Far West football teams.

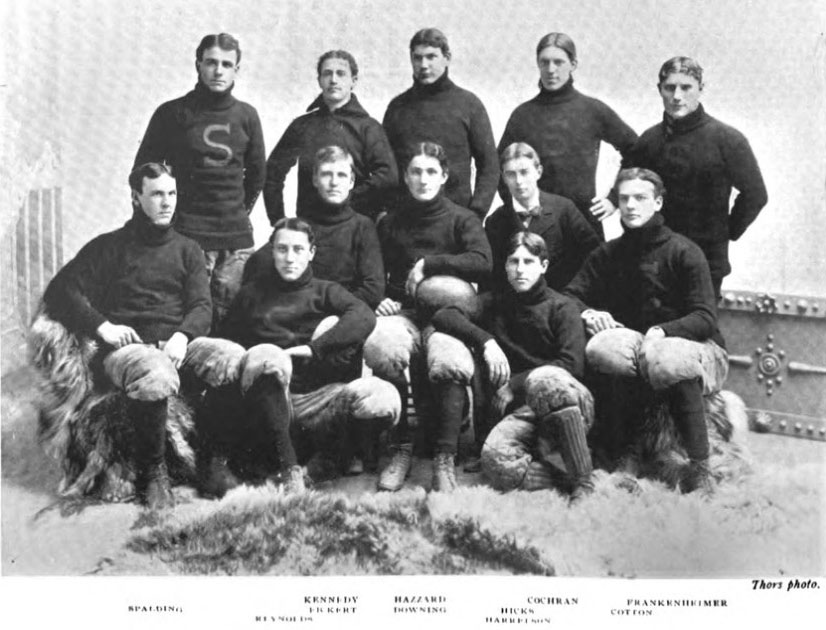

1894 Stanford Football Team (Stanford University Quad Yearbook Class of 1895)

When Bliss took a coaching position at Haverford College in Pennsylvania for 1894, Camp returned to California and directed the Stanford team throughout the season with the assistance of student manager/treasurer Herbert Hoover, the future President of the United States.

Both Camp and Hoover were interested in Stagg's proposal to play two Chicago vs Stanford games. The telegrams exchanged between California and Chicago gave no indication of any purpose for scheduling the games other than financial.

So Stagg scheduled four games for his team's Western tour. The first two were against Stanford, at the Haight Street Grounds in San Francisco Christmas day and the second at Athletic Park in Los Angeles December 29. The opponent for the third contest was the Reliance Athletic Club in San Francisco January 1. The fourth game would be played on the way home against the Salt Lake YMCA in Utah January 4.

A kindly lady offered the use of her private Pullman car for the trip to California. Stagg accepted without examining the car, which nearly created a disaster. It turned out to be a show car that had been condemned and put into retirement. At the top of the Rockies, the wooden coach caught fire. The Chicago team successfully fought the fire with axes and water. The car was abandoned at Sacramento, and the team continued to San Francisco without further incident.

Stanford had won three of their five games, which included three contests against the Reliance Athletic Club in Oakland and one against archrival California, which fell 6-0 November 29.

The Chicago-Stanford game generated a great deal of interest in the San Francisco area as indicated by the amount of betting on the contest, with Chicago ranking as a 5-3 favorite. An article datelined San Francisco in the Chicago Record Christmas day stated that "the college population of the city is wild with excitement" about the game. "Every man in Stagg's team is in the best of shape and is confident of success."

However, Stanford had not enjoyed the same preparation as their Midwest foes. "The Stanford team ... are in good condition, but not at their best. University duties have rendered systematic training impossible. Since the game with Berkeley they have not had one hard practice. In the preliminary work of the past week the second eleven has not taken part, hence the 'varsity has virtually confined its work to signal practice. ... A great deal hinges upon Stanford's power of endurance. While Stanford has been training hard for wind, Stanford has been studying for the examinations. The Chicago men indulged in three and five-mile runs at all stopping places en route."

Haight Street Grounds, San Francisco (San Francisco Public Library)

A crowd estimated as anywhere from 2,000 to 10,000 watched the scrappy Stanford eleven hold Chicago scoreless in the first half. However, despite having a stiff breeze at their backs, the home team could not score themselves, moving across midfield just once by recovering a Chicago fumble. Even though Stagg had played for Camp at Yale, the Maroons used a different method of tackling from Stanford. "Instead of following Camp's instructions to tackle low, they (Chicago) tackled high and low, and frequently a Stanford player was brought down by a neck or head hold."

Maroons Denied Touchdown

The Maroons came within inches of scoring when LE John Lamay made the run of the day. Starting from his 10, he dodged through the Stanford line and, picking up excellent interference, ran to the five before being tackled by A. B. Spalding. But the defense dug in, and Chicago faced last down inside the one. The ball carrier disappeared into a mass of bodies. "Referee Pringle blew his whistle, and the mass of arms and legs and tangled hair was cleared away. The Chicago substitutes swung their red jerseys, yelled "Touchdown!" and madly hugged each other. But the Stanford people kicked and said the ball was not over the line, and Pringle agreed with them. There was tremendous enthusiasm on the part of Stanford. Coats and hats were taken off and flung high in the air, while shrieks of 'No touchdown!'" Stanford punted to midfield as time was called.

Convinced they had scored in the last minute, the Maroons were not in a good mood as they left the field. Chicago QB Frank Hering told the umpire, Warren Olney, that the officiating was "cheesy" and unfair to the visiting team whereupon Olney punched the Chicago player in the nose. Police rushed in and ended the scrap. When Olney refused to return for the second half, a substitute official was obtained.

Chicago Dominates Second Half

The disparity in training showed up in the second half as the visitors scored 24 points on four touchdowns worth four points each and four two-point goals after touchdowns. Stanford managed to score one touchdown but missed the point after for four points.

After the ten-minute intermission, Chicago continued where they left off at the end of the first half, but this time scored a touchdown on their first possession. FB Henry Gale gained repeatedly up the middle to set up FB Clarence Herschberger's end run to break the scoring ice. 6-0 Chicago

When the Midwesterners got the ball back, they moved the ball to the Stanford five where they were finally stopped. But that only delayed the inevitable. When the Palo Alto men punted back, Frederick Nichols ran the ball back to the Stanford 25. Addison Ewing, D.D., L.L.D., an ordained minister, scored the touchdown this time, and Herschberger kicked goal. 12-0 Chicago

Even when Stanford made a good play, it backfired on them. Herschberger's punt was blocked, but Nichols grabbed the ball and, "aided by magnificent interference," ran 70 yards for a touchdown. 18-0 Chicago

Under the rules of the day, the team that scored a touchdown could choose to receive the next kickoff. And that's what Chicago did. Aided by a 10-yard offside penalty on Stanford, the Maroons quickly moved to Stanford's 20 on Herschberger's 40y run around left end. Captain Charles Allen swept that same side ito the end zone on the next play. 24-0 Chicago

Stanford Avoids Shutout

A Chicago miscue finally allowed Stanford to avoid a shutout in the final minutes. After recovering a fumble in Chicago territory, Stanford moved to the eight, where they lost the ball on a fumble. Herschberger immediately lined up in punt formation. He made a low kick that Stanford blocked. The ball bounded behind the goal line, and J. B. Frankenheimer fell on it for a touchdown. M. H. Kennedy failed to kick the goal. Chicago 24 Stanford 4

Stagg after the game: "I felt confident from the first that the Chicago team would win the battle, despite the fact that the Stanfords largely outweighed their competitors. Yet I knew that Walter Camp had coached the Stanfords, and that as a result the team would prove no despicable competitor. This was proved in the first half, which was stubbornly contested and in which the honors were nearly even. Stanford's defense in the first half was superb. Their tackling was low and hard, and the whole team to a man took part in it. In fact, the defense was so strong it had a noticeable effect on the Chicago offensive play in that the players did not go in with as much dash as in the second half. If anything, the Stanfords had more dash in the first half than the Chicagos."

Given four more days to prepare, Stanford won the rematch in Los Angeles, 12-0. Then the Reliance Athletic Club defeated Chicago back in San Francisco January 1. Three days later, the Maroons completed their Western excursion with a 52-0 thumping of the Salt Lake YMCA.

References:

Highlights of College Football, John Durant and Les Etter (1970)

Stagg University: The Rise, Decline & Fall of Big-Time Football at Chicago, Robin Lester (1995)

Walter Camp and the Creation of American Football, Roger R. Tamte (2018)

Highlights of College Football, John Durant and Les Etter (1970)

Stagg University: The Rise, Decline & Fall of Big-Time Football at Chicago, Robin Lester (1995)

Walter Camp and the Creation of American Football, Roger R. Tamte (2018)