Clash of Titans

Games featuring a future Hall of Fame coach on each sideline.

November 12, 1892: Yale @ Pennsylvania

Walter Camp vs George W. Woodruff

Wedge vs Plough

Walter Camp was introduced to American rugby when he enrolled at Yale as a freshman in 1876. Eugene Baker, the senior captain of the Yale team, was so impressed with Camp's conscientious effort and running speed that he selected the freshman for the team. But Baker went even further. Impressed with Camp's study of the rugby football rule book, the captain brought the freshman with him when he met with Harvard to negotiate the rules for Yale's second meeting with their archrival.

Baker represented Yale at an historic conference a week later where he joined with student leaders from Princeton, Harvard, and Columbia to form an association to promote and manage rugby. The sport had migrated to the United States from England, where the game was played and managed by athletic and social clubs outside the academic community. But across the pond, rugby joined rowing, baseball, soccer, and track and field as sports played by college teams.

Camp quickly fell in love with rugby. By his junior year, he was the Yale captain, which meant that he ran the team the way a coach would in later years. An instinctive innovator, he tinkered with the strategies of the game. For example, he designated one player as the "snapback" for each scrum (a forerunner of the center position in today's football) and positioned a "quarterback" closer to the line so that he could grab the kicked-back ball before an opponent got to it and toss it back to the "halfback," which was his position on the Yale team.

Camp Transforms Rugby into Football

When Camp graduated from Yale in 1882 and entered medical school, he became an advisor to the Eli football team. That kept him involved in the evolution of the game from the restrictive rules of British rugby to the more varied and open American game. In 1883, he dropped out of medical school and went to work for the New Haven Clock Company, eventually working his way up to chairman of the board of directors.

One of Camp's ideas that caught on was the concept of interference. Rugby didn't allow offensive players to precede the ball carrier and "in any way interrupt or obstruct" opposing players. But an 1888 rules change allowed an offensive player ahead of the ball carrier to interfere with (block) his opponent if he did it with his body only—no hands or arms.

In 1888, the Yale football captain, William "Pa" Corbin, asked Camp to coach the team. Corbin wanted Walter to take over all the duties that captains had previously performed. Camp agreed to the proposal, which did not involve a salary. Corbin would in effect be a player/assistant coach.

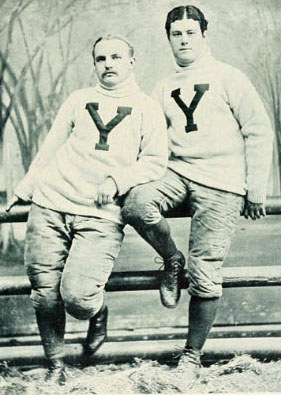

Walter Camp as a Yale freshman; George Washington Woodruff

Camp believed in rigorous practices with no rest or respite allowed. The stamina players developed was a major factor in Yale losing only two games in the five years he coached the team (1888-92).

The 1892 Yale Eli were 10-0 as they traveled to Philadelphia to face Pennsylvania.

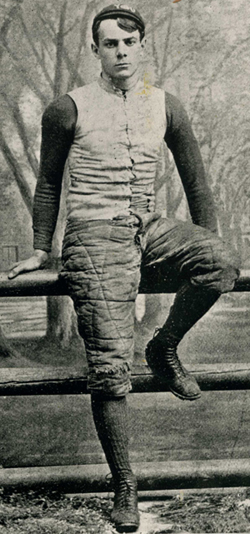

Featured Player

Frank Hinkey, weighing only 155lb and standing only 5'9" tall his senior year, was not big for a football player even by 1892 standards. But no man ever tackled harder or more often than the fiery Yale end. According to Highlights of College Football, "He did not thrust the interference aside with great strenght ..., but he always managed to get his hands on the man with the ball. 'He drifted through the interference like a disembodied spirit," recalled Walter Camp. "He weaved through it with a sudden, sinuous glide," said another observer.

"He tackled like a fiend. He grabbed the runner at the knees, turned with him in midair and using the runner's own momentum, hurled him headlong to the ground. Often his victim would be stretched out flat facing the direction from which he had come."

The press nicknamed him the "Living Flame," the "Silent Man," and the "Shadowy End."

When he came to Yale in 1891, he had consumption (tuberculosis). "I went out for football against the doctor's orders," he wrote to a friend, "but I'm not going to do it again." He did not keep that promise.

Hinkey played in only one losing game in four years, 6-0 to Princeton in 1893, his junior year. It's probably no coincidence that the Eli lost after Hinkey was carried off the field unconscious early in the game.

Hinkey was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1951, the year it was founded. |

|

Camp Disciple Improves Penn Program

The clash with Penn pitted Camp against one of his former players. George Washington Woodruff was Yale's right guard from 1885-88. Like Camp, Woodruff had never heard of football when he arrived at Yale at age 21. He was described as "a square-faced block of a man, one of the strongest on campus."

After graduating from Yale in 1889, George Woodruff returned to his native state of Pennsylvania and coached at several elite secondary schools. Tired of losing to Yale, Harvard, and Princeton, the University of Pennsylvania Athletic Association hired Woodruff as their head football coach in 1892. He received free tuition to the Penn Law School and a $1,300 salary.

The Camp disciple immediately improved the team, which started the season with 12 straight wins. The next week, the Quakers gained their first victory in 17 tries against nearby rival Princeton.

While Harvard had introduced the "Flying Wedge," Woodruff created his variation, the "Plough," at Penn.

The brainchild of a Boston engineer who had never played football, the Flying Wedge was first used on kickoffs. The players lined up in a "V" formation with the kicker forming the point of the V. Except for one player, the halfback, the two sides of the V started forward, one behind the other on each side of the V, and converged in front of the ball. When they reached him, the kicker touched the ball with his foot (the "kickoff"), picked it up as allowed by the rules of the day, and passed it to the halfback waiting behind him and the walls of blockers. The V-shaped formation bore down on the weakest link on the opponent's line of players ten yards away. The Flying Wedge was extremely successful in gaining yardage but also a primary cause of serious injuries and even deaths as multiple offensive players full speed crashed into one opponent.

The wedge concept was soon applied to all offensive plays since there were no rules governing the number of players on the scrimmage line or in motion before the snap of the ball.

Woodruff's "Plough" was the same as the Flying Wedge except that he put several players at the front of the formation instead of just one. The formation was also called "guards back" because both guards lined up several yards behind the line of scrimmage, one in front of the other. About four yards behind them were three other players, the fullback and both halfbacks. One of the backs took a handoff while the players in front of hiim all plowed forward, proving "interference" for the runner. The blockers focused their attention on one opponent on the defensive line, blasting a hole through the defender's position.

As part of an 1895 push to make the game safer, the Flying Wedge would be effectively abolished by rules changes that permitted only three offensive players behind the line of scrimmage and just one offensive player to be in forward motion

before the snap.

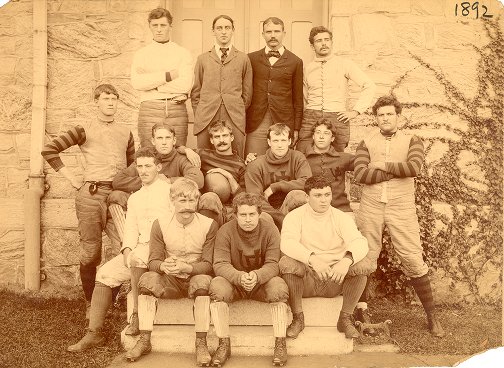

1892 Pennsylvania football team

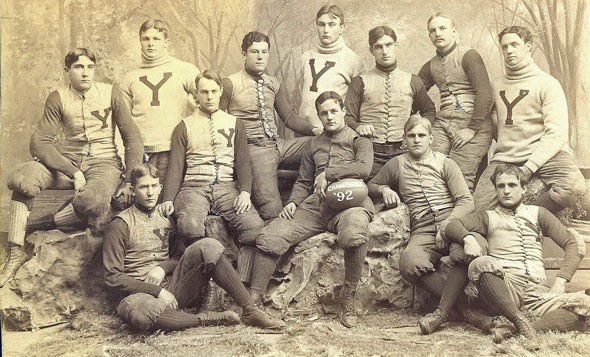

1892 Yale football team

Agility Beats Size

The reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer wrote: "Although the Pennsylvania men were considerably heavier than their opponents, their great weight was completely overcome by the agility of the men from New Haven."

The crowd of 12,000 at Manhattan Field, with three times as many Yale rooters as hometowners, saw the visitors take charge right away. Finding more success around the ends than through the center, the Eli moved smartly to Penn's five before surrendering the ball on downs.

But Yale scored a minute later on a strange play. Penn HB Harry Thayer punted from behind the goal line but the ball struck the goal post, and Yale's A. H. Wallis grabbed it and ran over for a touchdown. That episode epitomized what would be a long afternoon for the Quakers. With the rugby mentality still having an impact, kicking was still favored in the scoring over touchdowns. So the four points for the touchdown and two points for the point after touchdown. Yale 6 Pennsylvania 0

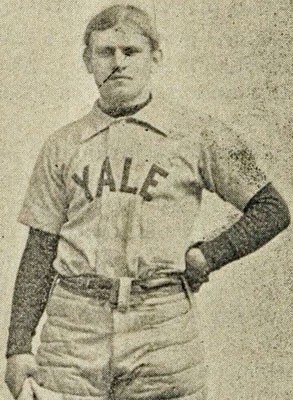

L-R: C. D. Bliss, A. H. Thayer, Laurie Bliss

"Laurie and C. D. Bliss played like fiends. Scarcely was the ball snapped back until they were off like a whirlwind and would tear through Pennsylvania's line and circle the ends for great gains. (FB Frank) Butterworth also charged the line to good effect and punted long and accurately."

Eli Pull Away

The next time Yale got the ball, they moved close enough for Vance McCormick to try a field goal that failed. But the Eli got the ball right back on a fumble, and this time were not to be denied. Laurie Bliss did the honors with a dash through the center for the touchdown. 12-0 Yale

For some reason, Penn punted on second down. Wallace Winter returned the pigskin 15y to the Penn 45. On the next snap, Laurie Bliss took a lateral and skirted right end behind fine blocking into the end zone. Yale 16 Penn 0

Yale's last score of the half came when Thayer kicked to Laurie Bliss, who took the ball on the ten and raced 90y behind outstanding blocking for a touchdown. Yale 22 Penn 0

In the final minutes, Penn's Plough formation finally gained ground into Yale territory. Runs by Camp, Thayer, and Delabaree moved the ball to the five where the Eli finally stopped the onslaught.

Penn held Yale to just six points in the second half but still couldn't score on the Eli defense. C. Bliss's 70y run around left end produced the final points.

As they did near the end of the first half, the Quakers marched to the Yale five, but a holding penalty turned the ball over in accordance with the rules of the day.

Final score: Yale 28 Pennsylvania 0

Yale completed another undefeated, untied, unscored-upon season in 1892, their third in the five years since Corbin asked Camp to coach.

References

Highlights of College Football, John Durant and Les Etter (1970)

The Opening Kickoff: The Tumultuous Birth of a Football Nation, Dave Revsine (2014)

Walter Camp and the Creation of American Football, Roger Tamte (2018)

Highlights of College Football, John Durant and Les Etter (1970)

The Opening Kickoff: The Tumultuous Birth of a Football Nation, Dave Revsine (2014)

Walter Camp and the Creation of American Football, Roger Tamte (2018)